Bunjevci

South Slavic ethnic group From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

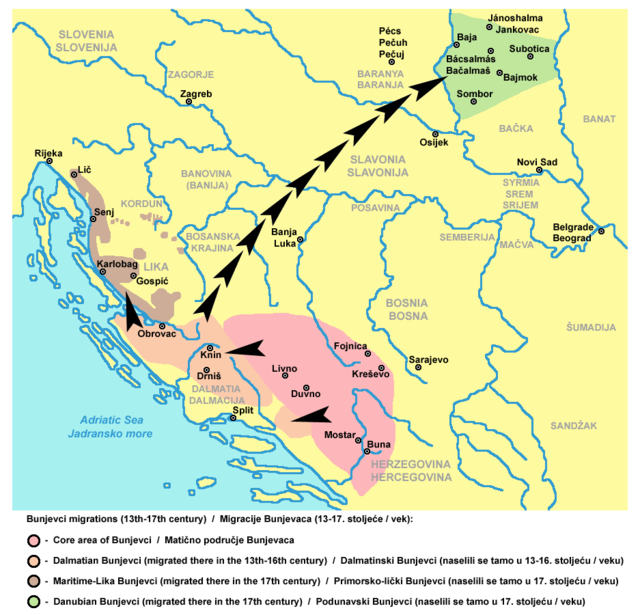

Bunjevci (Serbo-Croatian: Bunjevci / Буњевци, pronounced [bǔɲeːʋtsi, bǔː-]; singular masculine: Bunjevac / Буњевац, feminine: Bunjevka / Буњевка) are a South Slavic sub-ethnic group of Croats living mostly in the Bačka area of northern Serbia and southern Hungary (Bács-Kiskun County), particularly in Baja and surroundings, in Croatia (e.g. Primorje-Gorski Kotar County, Lika-Senj County, Slavonia, Split-Dalmatia County, Vukovar-Srijem County), and in Bosnia-Herzegovina. They originate from Western Herzegovina. As a result of the Ottoman conquest, some of them migrated to Dalmatia, from there to Lika and the Croatian Littoral, and in the 17th century to the Bácska area of Hungary.[2]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Unknown | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | (unknown) |

| Croatia | (unknown) |

| Hungary | c. 1,500 (2011 census) |

| Serbia | 11,104 (2022 census)[1] |

| Languages | |

| Serbo-Croatian (Bunjevac dialect) | |

| Religion | |

| Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Šokci, Croats and other South Slavs | |

Bunjevci who remained in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as those in modern Croatia today, maintain that designation chiefly as a regional identity, and declare as ethnic Croats.[3] Those who emigrated to Hungary underwent an extensive process of integration and assimilation.[4] In the 18th and 19th century they made up a significant part of the population of Bačka.[5][6] The government of Hungary considers the Bunjevac community to be part of the Croatian minority.[7]

Bunjevci in Serbia and Hungary are split between those who see themselves as a Croatian sub-ethnic group (bunjevački Hrvati) and those who identify themselves as a distinct ethnic group with their own language.[8] The latter are represented in Serbia by the Bunjevac National Council,[9][10] and the former by the Croat National Council.[11][12]

Bunjevci are mainly Catholic and the majority still speaks Neo-Shtokavian Younger Ikavian dialect of the Serbo-Croatian pluricentric language with certain archaic characteristics. Within the Bunjevac community and between Serbia and Croatia, there is an unresolved political identity conflict regarding ethnicity and nationality of Bunjevci and an ongoing language battle over the status of the Bunjevac speech as well.[13][14][15]

Ethnology

Summarize

Perspective

Ethnonym

Their endonym, used in Serbo-Croatian, is Bunjevci (sing. Bunjevac) (Serbo-Croatian pronunciation: [bǔɲeʋtsi]).[16] In Hungarian their name is bunyevácok, in Dutch Boenjewatsen, and in German Bunjewatzen. According to Petar Skok they also called themselves in Bačka as Šokci (sing. Šokac), while Hungarians in Szeged also called them as Dalmát (Dalmatians; Dalmatini),[17] which they also used for themselves in Hungary.[18] In addition, the term meant Catholic (Croat) population from Livanjsko field up to Montenegro which was mostly considered by the neighbor Serbian Orthodox population,[19] while at Peroj in Istria it was a pejorative name for Croats as well pobunjevčit pejoratively meant "become Catholic".[17] In the 20th century hinterland of Novi Vinodolski, called as Krmpote, the Primorje (Littoral or Coastal) Bunjevci were economically less powerful rural population and hence it had an attribution of "otherness" with negative connotation by urban citizens. Compared to Sveti Juraj they were more powerful and refused to call themselves Bunjevci because of such broad connotation and rather used "Planinari" (Mountaineers), and the citizens name "Seljari" had negative and mockery connotation by Bunjevci.[20] In the territory from Krmpote to Sv. Marija Magdalena in North Dalmatia there also existed multilayered regional identities Primorci and Podgorci, local Krmpoćani, while the subethnic term Bunjevci loses identity on the boundary with Velebit Podgorje.[21]

The earliest mention of the ethnonym is argued to be in 1550 and 1561 when in Ottoman defter is recorded certain Martin Bunavacz in Baranja.[22] However, the name was most probably erroneously transcribed (Ottoman's rarely recorded surname, being rather his father's name, which itself is possibly Dunavacz).[23][24] The earliest certain mention date from the early 17th century, for example in Bačka is from 1622 when was recorded parochia detta Bunieuzi nell' arcivescovato Colociense.[23][25] In Venetian Dalmatia there was Nicola Bunieuaz (1662, 1680), in Donje Moravice of Zrinski family was Manojlo Bunieuach (1670), and in Slavonia Paval Bunyevacz (1697) and Nikola Bunjevac (1698) from Bosnia.[26] Surname became also present in Orthodox community, denoting from their perspective somebody who came from a foreign, Catholic community.[27] The ethnonym is also mentioned by Bishop of Senj, Martin Brajković, in 1702 whose recorded folk tradition knew for the existence of five ethnic identities which constitute the population of Lika and Krbava, one of them being Catholic Vlachs also known as Bunjevci (Valachi Bunyevacz).[28] In 1712–1714 census of Lika and Krbava was recorded only one Bunieuacz (Vid Modrich), however the military government usually used alternative term Valachi Catolici, while Luigi Ferdinando Marsili called them Meerkroaten (Littoral Croats).[29][30] Alberto Fortis in Viaggio in Dalmazia ("Journey to Dalmatia") describing the Velebit (Montagne della Morlacca) recorded that the population was different from the earlier and called themselves as Bunjevci because they came from area of Buna in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[31] 1828 writing by Colonel Ivan Murgić probably had the last original testimony of Lika-Primorje Bunjevci about their traditional identity, in which they said to be "We are hardworking brothers Bunjevci", while regarding (Catholic) confession always as "I am true Bunjevac".[32] In general, the name came into common usage in literature and official documents only since the second half of the 18th and early 19th century.[33]

The etymological derivation of their ethnonym is unknown.[34] There are several theories about the origin of their name. The most common is that the name derives from the river Buna in central Herzegovina,[17] however, although preserved in Littoral and mostly in Podunavlje branch folk oral tradition, linguists and historians generally dismiss such derivation.[34][35] Another theory is that the name comes from the term Bunja, a traditional shepherd transhumance stone house[36] in Dalmatia similar to Kažun in Istria, meaning people who live in such type of houses.[22][37] Derivation from a Vlach personal name Bun/Bunj deriving from Latin name Bonifacius (with related Slavic names Bunjo, Bunjak, Bunjac, Bunac, Bunoje, Bunilo, Bunislav, Bunuš; Vlach clans of Bunčić, Bunović, and Bunuševci) is getting prominence recently.[17][38][39] Other also propose pejorative nickname Obonjavci which is recorded since 1199 in Zadar probably meaning soldiers without order and discipline,[40] and verb "buniti se" (to protest).[41]

History

Summarize

Perspective

Origin

According to modern ethnological studies, Bunjevci are a South Slavic people with some elements of non-Slavic ancestry, with partial Vlach-Arbanasi anthroponymy structure (20%;[26] also surnames of Muslim and non-Bunjevci Croatian origin shows a continuous process of assimilation of unrelated families[42][43]),[21] originating from Vlach-Croatian ethnic symbiosis of Ikavian Chakavian/Chakavian-Shtokavian language group, with some similarities to Vlach-Montenegrin symbiosis, but both being more archaic and different from the Vlach-Serbian symbiosis of Ekavian/Jekavian-Shtokavian group.[44] Although some scholars considered them as Slavicized Vlachs,[45][46] such argumentation is poorly substantiated and misunderstanding the meaning of the term Vlach,[47] as other scholars emphasize, they were Slavs and the term Vlach in the historical context of the 16th century did not mean some distinctive Romance ethnolinguistic identity, but an Ottoman social class which mostly included people who were not of Vlachian origin in strict sense.[48][49] Bunjevci were not a separate ethnic group of Vlach-Romance origin, there's no evidence they ever spoke a Romance language, designated themselves as Vlachs or considered themselves as ethnically different from near Slavic-speaking people (Croats, Bosnians and Serbs).[50] The emergence of the identity of Bunjevci is related to the historical, social and confessional (Vlachian Orthodox Rkaći vs Vlachian Catholic Bunjevci) dichotomies and events related to the Ottoman period on the so-called Triplex Confinium (the boundary between Venetian, Ottoman, and Habsburg Empire).[51]

Some scholars consider that the area of origin could have been between rivers Buna in Herzegovina and Bunë in Albania, along with the Adriatic-Dinaric belt (south Dalmatia and its hinterland, Boka Kotorska Bay, the coast of Montenegro and a part of its hinterland),[52] seemingly encompassing the territory of the so-called Red Croatia, regardless of the issue whether the entity is historically founded, which was partly inhabited by Croats according to Byzantine sources from 11th and 12th century.[52][53] However, the Buna thesis reached popularity more due to mythologization of the old legend rather than proper evidence and historical facts, being historically improbable.[54][55] Based on modern historiographical studies and archival research, as well dialectological and confessional identity, Bunjevci originated from Western Herzegovina (lands east of river Cetina and west of river Neretva).[56] The core of the Bunjevci was formed by the katuns or djamaats of Krmpote, Vojnići/Vojihnići and Sladovići recorded in 1477 as part of the Sanjak of Herzegovina.[57][58] Some historians like Stjepan Pavičić and Mario Petrić consider they belonged to the broader population of Croatian Ikavian people living in the Dalmatian and Bosnian hinterland.[59] Not all Catholic Vlachs in Croatia were of Bunjevci or Herzegovinian origin.[60] Although initially in the Ottoman service, Bunjevci since the early 17th century had complex relations with Ottomans, Venetians and Habsburgs, regularly migrating and changing sides.[61]

It is considered that from Western Herzegovina they emigrated to Dalmatia, where existed at least since the 1520s, and from there later to Bačka, as well as Lika, Primorje and Gorski Kotar.[62] This with a political situation divided the community into four groups, Western Herzegovinian (Ottoman), Dalmatian (Venetian), Lika-Primorje (Habsburg), and Podunavlje (Hungarian),[63] although the ethnologists often consider the first two as one group (broad Dalmatian) from which other diverged.[2][30][64]

In historical documents for them were also used alternative term Uskoks,[62][65] Dalmatians,[62][66] Catholic Vlachs/Morlachs (Catholische Walahen, Morlachi chatolici),[67] Catholic Rascians (Rasciani Catolichi, the term had transconfessional meaning),[68][30] Iliri, Horvati, Meerkroaten, Likaner, Illyrians.[69][21][31] In the territory of Croatian Military Frontier happened complex ethnic-demographic integrations, with Ledenice being one of the earliest examples of Croatian-Vlach-Bunjevac integration when an anonymous priest from Senj in 1696 calls them as nostris Croatis, while captain Coronini in 1697 as Croati venturini, at the same time (1693), chiefs of Zdunići in Ledenice emphasized their Krmpote ancestry.[30] Contemporary sources describe them as "gente effrene", "natio bellicosissima" and "katolische Stamm".[70]

Early modern period and Austro-Hungarian Empire

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2021) |

The migrations to Dalmatia were influenced by Ottomans conquest in the late 15th and early 16th century. In parts west of river Krka in Northern Dalmatia of the then Sanjak of Klis, in 1636 roughly lived 13,700 Catholics who could be related to the Bunjevci.[71]

The first migration to Primorje is considered to have happened in 1605 when around 50 families from Krmpota near Zemunik settled in Lič near Fužine by Danilo Frankol, captain of Senj, in agreement with Nikola and Juraj Zrinski,[37][72] and with several waves until 1647 settling in Lič, the hinterland of Senj (Ledenice, Krmpote – Sv. Jakov, Krivi Put, Senjska draga), and some to Pag and Istria. Some also arrived during the Cretan War (1645–1669), and after the Ottomans' defeat in Lika (1683–1687), some littoral Bunjevci moved to settlements in Lika, like Pazarište, Smiljan, Gospićko field, Široka Kula, valley of Ričice and Hotuče.[21] According to the common theory based on historical documents happened at least three big migrations to Podunavlje, although some probably already happened in the 16th century,[73] first of 2,000 families from the beginning of the 17th century (1608,[61] without Franciscan friars[74]), second in the mid-17th century during Cretan War, and third during Great Turkish War (1683–1699).[74] The Catholic Church in Subotica celebrates 1686 as the anniversary of the Bunjevac migration when the largest single migration did take place.[75] As a sign of gratitude and soldiery, some foreign soldiers (mostly unpaid frontiersmen), inclusive Bunjevci, received land pastures and Austrian-Hungarian citizenship. Up to the present day, the descendants of these mercenaries have still the right to be citizens of Hungary.

In 1788 the first Austrian population census was conducted – it called Bunjevci Illyrians and their language Illyrian. It listed 17,043 Illyrians in Subotica. In 1850 the Austrian census listed them under Dalmatians and counted 13,894 Dalmatians in the city. Despite this, they traditionally called themselves Bunjevci. The Austro-Hungarian censuses from 1869 onward to 1910 numbered the Bunjevci distinctly. They were referred to as "bunyevácok" or "dalmátok" (in the 1890 census). In 1880 the Austro-Hungarian authorities listed in Subotica a total of 26,637 Bunjevci and 31,824 in 1892. In 1910, 35.29% of the population of the Subotica city (or 33,390 people) were registered as "others"; these people were mainly Bunjevci. In 1921 Bunjevci were registered by the Royal Yugoslav authorities as speakers of Serbian or Croatian – the city of Subotica had 60,699 speakers of Serbian or Croatian or 66.73% of the total city population. Allegedly, 44,999 or 49.47% were Bunjevci. In the 1931 population census of the Royal Yugoslav authorities, 43,832 or 44.29% of the total Subotica population were Bunjevci.

The Croat national identity was adopted by some Bunjevci in the late 19th and early 20th century, especially by the majority of the Bunjevac clergy, notably one of the titular bishops of Kalocsa, Ivan Antunović (1815–1888), supported the notion of calling Bunjevci and Šokci with the name Croats.[76] Antunović, with journalist and ethnographer Ambrozije Šarčević (1820–1899), led Bunjevci national movement in the 19th century, and in 1880 was founded the Bunjevačka stranka ("the Bunjevac party"), an indigenous political party, mostly concentrated on language rights, preservation, and ethnographic work.[77] When their 1905 request for having police patrol and church services in Croatian was denied by Hungarian language policy, one group of 1,200 people converted to Orthodoxy.[77]

Yugoslavia

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2021) |

Around the time of World War I, was argued an idea that Bunjevci were not only a distinct group but also a fourth and smallest Yugoslav nation.[77] In October 1918, a part of Bunjevci held a national convention in Subotica and decided to secede Banat, Bačka and Baranja from the Kingdom of Hungary and to join Kingdom of Serbia. This was confirmed at the Great National Assembly of Serbs, Bunjevci, and other Slavs in Novi Sad, which proclaimed unification with the Kingdom of Serbia in November 1918. The assembly represented only a part of the whole population and did not met the principle of the self-determination of nations. The subsequent creation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (renamed Yugoslavia in 1929) brought most of the Bačka Bunjevci in the same country with the Croats (with some remaining in Hungary).

Between the World Wars, the national dispute included pro-Bunjevci, pro-Croatian, and pro-Serbian position. As Bunjevci were mostly supporters of the Croatian Peasant Party, and the ethnic boundary between Serbs and Croats was established on confessional line, they naturally felt closer to Croats.[78] During the late World War II, Partisan General Božidar Maslarić spoke on the national councils in Sombor and Subotica on 6 November 1944 and General Ivan Rukavina on Christmas in Tavankut in the name of the Communist Party about the Croatdom of the Bunjevci. After 1945, in SFR Yugoslavia the census of 1948 did not officially recognize the Bunjevci (nor Šokci), and instead merged their data with the Croats, even if a person would self-declare as a Bunjevac or Šokac.[79][better source needed] However, local schools used the Serbian version of Serbo-Croatian in Latin script, while during the 1990s even in Cyrillic script, policy interpreted as an attempt to assimilate them into the Serbian culture.[78] There are different opinions about the historical context of the content of document "Dekret 1945".[80][81][82]

Proponents of a distinct Bunjevac ethnicity regard this time as another dark period of encroachment on their identity and feel that this assimilation did not help in the preservation of their language. The censuses of 1953 and 1961 also listed all declared Bunjevci as Croats. The 1971 population census listed the Bunjevci separately under the municipal census in Subotica upon the personal request of the organization of Bunjevci in Subotica. It listed 14,892 Bunjevci or 10.15% of the population of Subotica. Despite this, the provincial and federal authorities listed the Bunjevci as Croats, together with the Šokci and considered them that way officially at all occasions. In 1981 the Bunjevci made a similar request – it showed 8,895 Bunjevci or 5.7% of the total population of Subotica. Robert Skenderović emphasizes that already before 1918 and the Communist rule, Bunjevci have made strong efforts to be recognized as part of the Croatian people.[83] Many, on an example of Donji Tavankut, also declared as Yugoslavs.[84]

Contemporary period

Croatia

Croatia considers the people from the Bunjevac communities as integral part of the Croatian nation, even though they live in the diaspora (e.g. Serbia and Hungary — Bunjevac Croats of Serbia and Hungary).

Hungary

In Hungary, Bunjevci are not recognized as a minority; the government consider them Croats.[85][7] The Bunjevac community is divided into a group who declare themselves as an independent Bunjevac people and those who see themselves as an integral part of the Croatian people. In April 2006, some members of the Bunjevac community and political activists, who are collaborating closely with the Bunjevac National Council in Serbia, started collecting signatures to register Bunjevci as an independent minority.[86] [citation needed] In Hungary, 1,000 valid subscriptions are needed to register an ethnic minority with historical presence. By the end of the given 60 days period, the initiative gained over 2,000 subscriptions of which cca. 1,700 were declared valid by national vote office and Budapest parliament gained a deadline of 9 January 2007 to solve the situation by approving or refusing the proposal.[citation needed] No other such initiative has reached that level ever since minority bill passed in 1992.[87] On 18 December the National Assembly of Hungary refused to accept the initiative (with 334 No and 18 Yes votes). The decision was based on the study of the Hungarian Academy of Science that denied the existence of an independent Bunjevac minority (they stated that Bunjevci are a Croatian subgroup).[citation needed] The opposition of Croatian minority leaders also played part in the outcome of the vote, and the opinion of Hungarian Academy of Sciences.[88] To this day, the descendants of Dalmatia or Illyria (Bunjevac) mercenaries who fought against the Turks, from the 17th century, still have the right to be citizens of Hungary (under strict conditions), even if they live outside the current Hungarian land borders.

Serbia

In Serbia, Croats (included the Croatian sub-ethnic group of Bunjevci and Šokci) were recognized as a minority in 2002 and reprecented by the Croat National Council and for those, who consider themself as a separate Bunjevac minority, are reprecented by the Bunjevac National Council in 2010.

The national councils receive funds from the state and province to finance their own governing body, cultural, and educational organisations.[89][90] The level of funding for the National Councils depends on the results of a census, in which the Serbian citizens can register and self-declare as belonging to a state-recognized minority of their choice.[91] [92] In the results of census taking is a disagreement between real ethnicity and declared ethnicity.[93] Most people, who declare that they belong to a specific ethnic/minority group, have come already for centuries from families with mixed family backgrounds (e.g. mixed marriages between different nationalities/ethnicities, interreligious marriages).

In the former Yugoslavia, Bunjevci were, along with Šokci, registered as the subcategory of Croatian ethnicity. Beginning in the late 1980s in Vojvodina, attempts were made to separate these two subcategories into distinct ethnicities, leading to a change in choices for ethnic affiliation in the 1991 Yugoslavian census. According to Kameda (2013), the categories of Bunjevac and Šokac were introduced for the purpose of reducing the number of Croatian population inside Serbia. Bunjevci were officially recognized as a separate ethnic group at the start of 1991. In 1991 census lived 74,808 Croats, and 21,434 Bunjevci in Vojvodina, while in the district of Subotica, there were approximately equal numbers of declared Croats and Bunjevci: 16,369 and 17,439.[84] In the administrative area of the city of Subotica region, there were 13,553 Bunjevci and 14,151 in 2011. The historically Bunjevac village of Donji Tavankut had 1,234 Croats, 787 Bunjevci, 190 Serbs and 137 declared as Yugoslavs. A 1996 survey by the local government in Subotica found that in the community, 94% of declared Croats agreed that Bunjevci were part of the Croatian nation, while 39% of declared Bunjevci supported this view.[94]

In the results of the 2022 census of the Republic of Serbia: 39,107 Croats are registered, of which the census methodology has not made a subdivision of percentage respondents identifying themselves as Bunjevac Croats. According to the same census, there are 11,104 citizens who have registered as Bunjevac, of which the results do not indicate how much respondents of these citizens considered themselves as sub-ethnic group of the Croatian people or as separate ethnicity, in conjunction with their belief of being a distinct Bunjevac people.[95]

National status dispute – Bunjevac question (Bunjevačko pitanje)

Disputes about the ethnic and national status of the Bunjevci trace back to the nationalist wave in the 19th century in Austria-Hungary and, their "national status" remained ambiguous since, as the debate revived by the Breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s.[96][97] The Bunjevac question entails also political obstacles concerning language politics, particular about Bunjevac dialect, that may polarize domestic politics in Serbia and inhibit regional cooperation particular between Croatia and Serbia.[98]

It has been argued that they are Croats, Serbs, and yet another as a fourth nation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes among the South Slavic nations.[96] In the period between 1920 and 1930 and again in 1940, there were three types of manipulation to neutralize their Croatian nationality, primarily emphasizing their ethnic distinctiveness from both the Croats and Serbs, that can be both Croats and Serbs or it's unimportant because both are Yugoslavs, and open denial of their ethnicity and religious belonging considering that Bunjevci and Šokci are Serbs of the Catholic faith.[99][100] The third was argued by Serbian academic elite, including Aleksa Ivić, Radivoj Simonović, Jovan Erdeljanović among others. Some Croatian authors reject these point of view as unfounded.[99]

Following the breakup of Yugoslavia, the Bunjevac community was, during the regime of Slobodan Milošević (a follower of the Greater Serbia ideology), officially granted the status of autochthonous people in 1996.[101] In the 1990s many Croats declared themselves as Bunjevac in order to avoid stigmatisation, which increased the number of self-declared Bunjevci. The self-declaration of Bunjevac was also aided by grass-roots demands for a separate Bunjevac nation.[102]

In early 2005, the Bunjevac issue (bunjevačko pitanje) was again popularized when the Vojvodina government decided to allow the official use of the Štokavian dialect with ikavian pronunciation "bunjevac speech with elements of national culture" (Bunjevački govor s elementima nacionalne kulture)[103][104] in schools – in the first year in Cyrillic script and in the following school years in Latin script. This was protested by the Serbian Bunjevac Croat community as an attempt of the government to widen the rift between the Bunjevac communities. They favour integration, regardless of whether some people declared themselves distinct, because minority rights (such as the right to use a minority language) are applied based on the number of members of the minority. As opposed to this, supporters of pro-Bunjevci option are accused Croats for attempts to assimilate Bunjevci.[105] In 2011, Bunjevac pro-Yugoslav politician Blaško Gabrić[106] and Bunjevac National Council, asked Serbian authorities to start juristic criminal responsibility procedure against those Croat minorities who are denying the existence of Bunjevci being an ethnicity, which is, according to them, violation of laws and constitution of the Republic of Serbia.[105]

Since 2006, some people of the Hungarian Bunjevac community and political activists, who are collaborating with the Serbian Bunjevac National Council, attempted to gain recognition as a separate ethnic group, but those initiatives have been rejected by the government, based on the opinion of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, who consider them part of the Croatian minority.[7]

The former president of Serbia, Tomislav Nikolić, stated in 2013 that Bunjevci are "You are neither Serbs nor Croats, but an authentic Slavic nation, ..."[107][108][109] The Croat National Council and Croatian MEPs responded critical to his statement, stating that the Serbian government is encouraging the division of the Croatian minority into Bunjevci and Šokci, and favouring those Bunjevci who do not declare themselves to be Croats.[110] Until 2016 the Bunjevac National Council believed that Bunjevci presumably originate from Dacia[111] and then added Dardania[112] to support their claim that they are not part of the Croatian Nation.

In late September 2021, president of Croatia, Zoran Milanović, stated that "Croatia considers the Bunjevac community to be Croats".[113] The Bunjevac National Council responded harshly to his statement, stating that Bunjevci have been living in Subotica for 350 years and that the difference between Bunjevci and Croats, according to their opinion, is attested in historical sources.[114][115]

Today, both major parts of the community (the pro-independent Bunjevac one and the pro-Croatian one) continue to consider themselves ethnologically as Bunjevci, although each subscribing to its own interpretation of the term. The government of Serbia implemented two laws to protect the minority rights of the divided Bunjevac community:

1. Croatian minority (Bunjevci, Croats, Šokci) in the Republic of Serbia: "Pursuant to the law on the Rights and liberty of national minorities (adopted by the Assembly of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, on 26 February 2002), the Croat national minority was guaranteed, for the first time ever, the status of minority. Although they carry several regional and sub-ethnic names (e.g. "Bunjevci" and "Šokci"), Croats in Vojvodina constitute an integral part of the Croatian people, who in the capacity of an autochthone people reside in the parts of the Srijem of the Vojvodina province, in the Banat and the Bačka region, but also in a significant number in Belgrade. From the historical perspective, this population, in its overwhelming number, has been for centuries an indigenous population."[116]

2. Bunjevac minority in the Republic of Serbia: "The constituting session of the Bunjevac National Minority Council was held on 14 June 2010 in Subotica. By the Ministry of Human and Minority Rights of the Republic of Serbia document No. 290-212-00-10/2010-06 of 26 July 2010 Bunjevac National Minority Council was entered into the national council register."[117]

However, many Bunjevci questioned the new categorization and continued to identify themselves not as a distinct ethnicity from Croatian but simply as Yugoslav, or, as a part of Croatian ethnicity in the frame of "Vojvodina Croats" (which includes Šokci).[118]

In summary, we can say that people nowaday, who prefer to identify themselves as Bunjevac or Bunjevac-Croat, have already come from ethnically mixed families for generations. Up to the present day, historical events are still influencing public opinion and media,[119] demographic movements, politics of national identity of different ethnic/minority groups,[120][121] language politics, and citizenship.[122][123]

Political parties

Bunjevac community oriented political parties in Croatia and Serbia e.g.:

- BGS – Bunjevci građani Srbije Bunjevci Citizens of Serbia (affiliated with the Bunjevac National Council)

- DSHV – Demokratski savez Hrvata u Vojvodini, Vojvodina/Serbia (umbrella political party of the Croat National Council)[124]

- HBS – Hrvatske bunjevačke stranke, Croatia[125][126]

- SBB – Savez bačkih Bunjevaca, Vojvodina/Serbia (umbrella political party of the Bunjevac National Council)[127]

Demographics

Summarize

Perspective

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2021) |

Croatia

(Further information Croats of Serbia)

Croatia considers the Bunjevac community an integral part of the Croatian nation, even though they live in the diaspora (e.g. Serbia and Hungary).

Hungary

In Hungary, the Bunjevac community is divided into a group who declare themselves as an independent Bunjevac people and those who see themselves as an integral part of the Croatian people. Hungary considers the Bunjevac community as integral part of the Croat ethnicity.

Towns and villages with a Bunjevac population (names of settlements in Serbo-Croatian listed in brackets) include Baja, Csávoly (Čavolj), Csikéria (Čikerija), Katymár (Kaćmar), and Tompa.

Serbia

(Further information Demographic history of Vojvodina and Demographic history of Bačka)

The Republic of Serbia is using a "segregated model of multiculturalism".[128] In Serbia, Bunjevci live in AP Vojvodina, mostly in the northern part of Bačka region. The community, however, has been divided around the issue of ethnic and national affiliation: in the 2011 census, in terms of ethnicity, 16,706 inhabitants of Vojvodina self-declared as Bunjevci and 47,033 as Croats. Not all of the Croats in Vojvodina have Bunjevac roots; the other big group are Šokci. In the 2022 census of the Republic of Serbia: 39,107 Croats and 11,104 Bunjevci are registered, of which the census methodology has not made a subdivision of percentage respondents identifying themselves as Bunjevac Croats or as a separate Bunjevac ethnicity, in conjunction with their belief of being a distinct Bunjevac people.[95]

In the Serbian Bunjevac community are people who have only economic based motives to declare to be Bunjevac Croat, to ensure access to the EU (e.g. labour migration, business, education). And there are citizens who declare that they are part of the Bunjevac community (pro-Bunjevac or pro-Croat one) to benefit from financial grants,[129] or just based on their personal feelings.

The largest concentration of Bunjevci in Serbia, is in the city of Subotica, which is their cultural and political center. Another significant urban center is the city of Sombor.

- Villages with Bunjevac population who are located in the administrative area of the city of Subotica: Ljutovo, Bikovo, Gornji Tavankut, Donji Tavankut, Đurđin, Mala Bosna, Stari Žednik, and Bajmok.

Language

Summarize

Perspective

Most members of the Bunjevac community in Serbia who speak Bunjevac dialect and Croatian language also speak mutually intelligible Serbian language. In Hungary, there is a growing interest in learning Bunjevac dialect and Croatian among citizens who have Bunjevac ancestors in their genealogical history line.[130]

Bunjevac dialect

The Bunjevac dialect (bunjevački dijalekt),[131] also known as Bunjevac speech (bunjevački govor),[132] is a sub-dialect of Neo-Shtokavian Younger Ikavian dialect of the Serbo-Croatian pluricentric language,[133] preserved among members of the Bunjevac community. Their accent is purely Ikavian, with /i/ for the Common Slavic vowels yat.[134] According to Croatia there are three historical-ethnological branches of Bunjevci and their dialect: Dalmatian, Danubian, and Littoral-Lika.[135] Its speakers largely use the Latin alphabet and are living in parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, different parts of Croatia, southern parts (inc. Budapest) of Hungary as well in the autonomous province Vojvodina of Serbia.

Opinions on the status of the Bunjevac dialect remain divided.[136][137][138][139] Bunjevac speech is considered a dialect or vernacular of the Serbo-Croatian pluricentric language, by linguists. It is noted by Andrew Hodges that it is mutually intelligible with the standard Serbian and Croatian varieties.[140] Popularly, the Bunjevac dialect is often referred to as "Bunjevac language" (bunjevački jezik) or Bunjevac mother tongue (materni jezik). At the political level, depending on goal and content of the political lobby, the general confusion concerning the definition of the terms language, dialect, speech, mother tongue, is cleverly exploited, resulting in an inconsistent use of the terms.[141][142][143]

Media

The Bunjevac community-oriented media in Serbia are predominantly controlled by editors of the lobby of the Bunjevac National Council or the Croat National Council. They both target readers in Serbia and abroad.

- Bunjevački Radio Tavankut[144]

- Digital information for Croats (Croinfo.rs)[145]

- Digital information for Vojvodina Croats (Zavod za kulturu vojvođanskih Hrvata)[146]

- Newspaper in Bunjevac dialect (Bunjevačke novine), published by the Bunjevac National Council in Subotica.[147]

- Newspaper in Croatian language (HRVATSKE novine)[148]

Heritage

Summarize

Perspective

The cultural center of Danube Bunjevci from Bačka district is the city of Subotica in Serbia, in Hungary it is the city of Baja in Bács-Kiskun county, while for the Littoral or Coastal Bunjevci in Croatia it is the city of Senj located in Lika-Senj county. As the former live in a region inhabited by a population of the same nationality, they are far more assimilated, show less appreciation for traditional clothing and heritage due to external factors, but although mostly aware of their identity there's indifference for connection to other Bunjevci branches in Lika and Danube.[149] Traditionally, Bunjevci of Bačka are associated with land and farming. Large, usually isolated farms in Northern Bačka called salaši are a significant part of their identity. Most of their folk customs (Bunjevački narodni običaji) celebrate the land, harvest, and horse-breeding. The Bunjevac heritage (Bunjevačka nošnja) is more than only folklore: it is a way of live for many people with Bunjevac ancestors, a tourist-economic value,[150] and unfortunately continues to be misused as a setting for personal and political interests.

Since the year 2010, members of the Bunjevac National Council have started to develop their own symbols (e.g. flag) and Bunjevac festivals and gatherings (e.g. "Dan Dužijance", "Dan velikog prela"), mostly close to the dates of the original traditional Bunjevac festivals and folklore gatherings of the Bunjevac Croats of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Hungary, and Serbia.

The Catholic Church is an important catalyst in preserving Bunjevac heritage, in particular the Franciscan Order has historical ties with the Bunjevac community.[151][152] Nowadays this is mainly due to the Diocese of Subotica and the efforts of e.g. mgr. dr. Andrija Anišić[153] and the venerable sister Eleonora Merković,[154][155] that the Christian significance of many Bunjevac customs (bunjevački običaji) are again appreciated, in contrast to the Communist and Socialist 20st century governing periods in the Balkans, where e.g. the harvest festival as Dužijanca, had only a secular character in public.

Also from the civilian population there are outstanding personalities (e.g. Ruža Juhas,[156] Kata Kuntić,[157] prof. dr. Gyula J. Obádovics,[158] Grgo Piuković,[159] Jozefa Skenderović)[160] who cherish and make efforts to preserve the Bunjevac heritage for future generations.

Cuisine

Bunjevac cuisine is a melting pot of multicultural culinary traditions from the Balkans (e.g. Turkish, Hungarian, Slavic).[citation needed] In 2016, Hilda Heinrich wrote a traditional Bunjevac cookbook with historical recipes.[161][162] The traditional cuisine of Coastal Bunjevci in Croatia has been described by Jasmina Jurković.[163] The organizations ZKVH [164] and the NSBNM [165] have made historical Bunjevac recipes digitally accessible. [166][167]

Costume

Wearing Bunjevac traditional ceremonial garments (Ruvo),[176] has a symbolic meaning in the context that it shows the belonging to a specific social/ethnic group, lifestyle, and status. The festive/working Bunjevac (folk) costume changed (bunjevačka nošnja) in different periods, due to urban, aristocratic and Western fashion influences, both in male and female costumes. The Bunjevac costume for women, in Hungary and Serbia, is based on the dress code in the time of Maria Theresa (1717–1780). The Bunjevci are living in different regions of Croatia,[177] Hungary,[178][179] and Serbia[180][181][182] with a unique collection of traditional costumes[183] with needlework.

- Beli vez or bili šling[184][185](Broderie Anglaise)[186] – open lace needle work

- Bunjevac footwear (wooden clogs,[187] mules (papuče),[188] boots)

- Goldwork (embroidery) – embroidery using metal threads (e.g. on mules for ladies and vests for men)[189][190]

- Mekane sare – rattling boot bells[191]

- Ruvo – Bunjevac traditional ceremonial garments. Dress tutorial[192] with Jelena Piuković. Headscarf tutorial[193] with Rožića Šimić.

- Zlatni novci – Gold coins necklaces was an indicator of style and wealth[194]

Dance

Dances from Vojvodina are most similar to the Slavonian dances in their liveliness and activity. The Bunjevci Croats from the Bačka region are renowned for their beautifully embroidered female dresses, made from real silk from France, and the rattling sound made by the male dancers' boots as they dance. New choreographies are still being created today based on old Bunjevac folk dances that have been handed down. Important in this context is the work of the folk dance teacher and choreographer Stevan Tonković[195] from Vojvodina, Serbia, and the folk dance group ensemble LADO[196] from Croatia.

- Bunjevačko momačko kolo – literally the bunjevac men's kolo, where one man dances with two women

- Divan – a meeting of young boys and girls for singing and dancing in a place far from their parents. The custom has been forbidden by church authorities already in the mid-19th century

- Kolo igra, tamburica svira[197] – the circle dance is usually performed amongst groups of at least three people and up to several dozen people. Dancers hold each other's hands or each other's waists. They form a circle, a single chain or multiple parallel lines.[198] According to Wilkes (1995), the kolo has an Illyrian origin as the dance seems to resemble dances depicted on funeral monuments of the Roman era[199]

- Malo kolo – is an old traditional dance from the Vojvodina region of Serbia, and far beyond

- Momacko nadigravanje – the men's competitive dance

- Podvikuje Bunjevačka Vila

- Tamburica Svira

- Tandračak

Feast

- Veliko bunjevačko prelo – festive gathering[200]

The central holidays are based on the Roman Catholic feasts: Christmas, Easter, St. John, and Pentecost with specific Bunjevac folk customs:

- Dužijanca – Day of Saint John the Baptist (Ivan Svitnjak): celebration of harvest end, and the most famous festival as well as a tourist attraction. It consists of several events (e.g. mowing competition, horse races, folklore fashion show competition, performances of Bunjevci folklore with dance and music) held in Bunjevci-populated places in Serbia (e.g. Bajmok, Donji Tavankut, Gornji Tavankut, Sombor, Subotica),[201] in Bosnia and Herzegovina (e.g. Mostar),[202] and in Hungary (e.g. Baja,[203] Gara, Tompa), with the central religious celebration of a Holy Mass and street procession.[204] The harvest festival Dužijanca has a tradition of more than 100 years (from 1911)[205] in Subotica. Bunjevci, who are represented by the Croat National Council, are organizing the harvest festival Dužijanca.[206] It is thanks to the pastor Blaško Stipan Rajić (1887-1951) of Subotica that the harvest thanksgiving Dužijanca became in 1911 an integral part of the church festivals.[207] In 2011, Subotica celebrated the 100th anniversary of Dužijanca.[208] And Bunjevci, who are gathered around the Bunjevac National Council, celebrating Dan Dužijance (from the first decennium of the 21st century).[209][210] In Sombor (Vojvodina), the divided Bunjevac community is celebrating together with the Šokac community, the harvest festival named Dužionica.[211][212] The celebration of harvest festivals dates back to ancient times and has a pagan background, festive thanksgiving in honor of the god of fertility. In the Balkan Region, the harvest festival with different names still occurs: in Senje "Doženjancija", in Lika "Dožinjancija", and in Zagora "Dožencija".[213]

- Kraljice – ceremonial processions held on Pentecost.[214][215][216] Vlach origins of Kraljice (Hora and Kolo).[217] Kraljice song.[218]

Festivals

- Bunjevac Song Contest, Subotica – Festival bunjevački pisama: A yearly competitive event with the aim to preserve, promote and popularize the musical culture of the Croatian ethnic group Bunjevac, especially new Bunjevac music and folk songs written in Bunjevac dialect.[219] The proposal to start the festival was made by Dr. Marko Sente from Subotica in 2000. The founders ware: Ana Čavrgov, Ljiljana Dulic Mészáros, Branko Ivankovic Radakovic, Siniša Jurić, Tomislav Kujundžić, Antonija Piuković, Marko Sente, Nela Skenderović, Stanislava Stantić Prćić, Vojislav Temunović, and Mira Temunović. The lyrics and music should represent the life and customs of Bačka Bunjevci; The text of the poem must be written in Ikavic or Ijekavic; A poem can have 3 or 4 verses.[220][221]

- Multicultural cooking and baking competition, Bajmok – Festival bunjevački ila: A yearly event, since 2005, organized by the local unit of the Bunjevac National Council.[222]

Handicraft

- Naïve Painting[223]

- Slamarke – Straw Art. Straw art is part of many cultures with an agricultural historical background[224][225]

- Molovanje – Wall patterned paint roller decoration technique still actively used in Croatia, Hungary, and Serbia.[226][227] The roller technique originated from wall decoration by stencil painting.[228][229][230]

Music instruments

Historical examination shows a diversity of instruments in the Balkan region. Several instruments are of Oriental origin. Main categories are: tambura, violin and fiddles, bagpipe, flute, accordion, and drums.

- Tambura – a plucked instrument used to accompany instrumental or vocal performances. The musical instrument is widespread in the Balkan region.

Religious devotion

- Krsno ime – referring to krsna slava, a celebration of a patron saint of the family, has existed among the Bunjevci as part of a historical veneration of elders[231]

- Religious straw objects and paintings for home, street procession, and church decoration.[232]

Songs

Bunjevci preserved a large number of folk songs,[233][234] such as Groktalice[235][236][237][238] (epic-lyric songs written in decasyllable – a poetic meter of ten syllables in poetic tradition of syllabic verse).

Wedding

One of the Bunjevac marriage customs is that the bride get money for each kiss she gives to wedding quests.[239]

Museums

Croatia

- Senj City Museum[240]

Hungary

Serbia

- Tavankut (virtual museum)[243]

Slovenia

- Regional Museum Maribor[244]

Notable people

Artists

- Branko Ištvančić (1967), filmmaker[245]

- Latinovits Zoltán (1931–1976) actor, Hungary

- Ana Milodanović (1926–2011),[246] straw artist

Ecclesiastical representatives

- Ivan Antunović (1815–1888),[247][248] priest, Archbischop and bischop of Budánovics Lajos,[249] and politician, Austro-Hungarian Empire

- Blaško Rajić (1878–1951)[250] Catholic priest, writer, and politician

Music

- Bartók Béla (1881–1945), composer (had several Bunjevac ancestors on father's side)

- Zvonko Bogdan (1942), singer (Bunjevac dialect), (Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia, Republic of Serbia)

Politicians

- Lázár Mészáros (1796–1858), general, Minister of War, Austro-Hungarian Empire (On mother's side)

Scientists

- Gaja Alaga (1924–1988), Croat theoretical physicist

- Josif Pančić (1814–1888), Serb academic botanist[251]

- Obádovics J. Gyula (1927) mathematician, Hungary

- Mirko Vidaković (1924–2002), Croat academic botaninist

Sport

- Zorán Kuntics and Goran Kopunovics footballers, Hungary[citation needed]

Writers

- Antun Gustav Matoš (1873–1914), Austro-Hungarian Empire[citation needed]

- Blaško Rajić (1878–1951)[citation needed]

See also

References

Sources and further reading

Organisations

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.