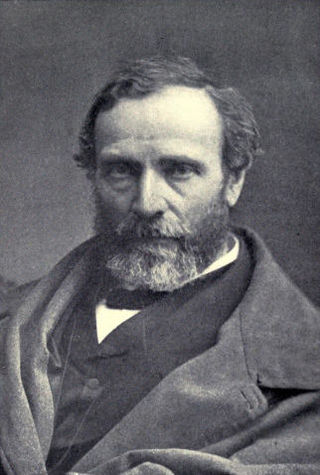

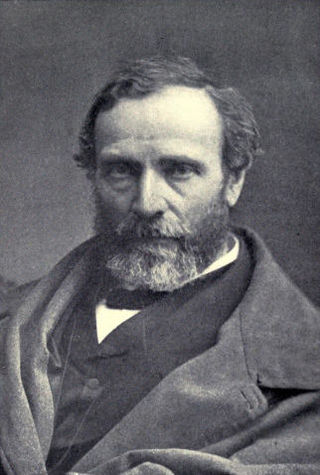

Arthur Hobhouse, 1st Baron Hobhouse

English lawyer and judge From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Arthur Hobhouse, 1st Baron Hobhouse, KCSI, CIE, PC, KC (10 November 1819 – 6 December 1904) was an English lawyer and judge.

Background and education

Born at Hadspen House, Somerset, Hobhouse was the fourth and youngest son of Henry Hobhouse, permanent under-secretary of state in the Home Office, by his wife Harriet, sixth daughter of John Turton of Sugnall Hall, Stafford. Edmund Hobhouse, Bishop of Nelson, and Reginald Hobhouse (1818–95), Archdeacon of Bodmin, were elder brothers. Passing at eleven from a private school to Eton, he remained there seven years (1830–7). In 1837 he went to Balliol College, Oxford, graduated B.A. in 1840 with a first class in classics, and proceeded M.A. in 1844. Entering at Lincoln's Inn on 22 April 1841, he was called to the bar on 6 May 1845, and soon acquired a large chancery and conveyancing practice.[1]

Early legal career

Summarize

Perspective

In 1862 he became a Queen's Counsel and a bencher of his inn, serving the office of treasurer in 1880–1 and practised in the Rolls Court (the civil division of the Court of Appeal). A severe illness in 1866 led him to retire from practice and accept the appointment of charity commissioner. Hobhouse threw himself into the work with energy. He was not only active in administration but advocated a reform of the law governing charitable endowments. The Endowed Schools Act, 1869, was a first step in that direction, and under that act Lord Lyttelton, Hobhouse, and Canon H. G. Robinson were appointed commissioners with large powers of reorganising endowed schools. Much was accomplished in regard to endowed schools, but the efforts of Hobhouse and his fellow commissioners received a check in 1871, when the House of Lords rejected their scheme for remodelling the Emanuel Hospital, Westminster. There followed a controversy which was distasteful to Hobhouse, and with little regret he retired in 1872 in order to succeed Sir James Fitzjames Stephen as law member of the council of the Governor-General of India. Hobhouse had meanwhile served on the royal commission on the operation of the Land Transfer Act in 1869.[1]

India

Summarize

Perspective

Hobhouse, "on his departure for India received strong hints that it would be desirable for him to slacken the pace of the legislative machine", which had been quickened by the consolidating and codifying activities of Fitzjames Stephen and of Stephen's immediate predecessor, Sir Henry Sumner Maine. That suggestion he approved. Whitley Stokes, secretary in the legislative department, was mainly responsible for the measures passed during Hobhouse's term of office, with the important exception of the Specific Relief Act, 1877, in which Hobhouse as an equity lawyer took an especial interest, and a revision of the law relating to the transfer of property, which became a statute after he left India. Of strong liberal sentiment, Hobhouse had small sympathy with the general policy of the government of India during the opening of Lord Lytton's viceroyalty. The attitude to Afghanistan was especially repugnant. He served from 1875 to 1877 as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Calcutta. On the conclusion of his term of office in 1877 he was made a K.C.S.I., and returning to England soon engaged in party politics as a thoroughgoing opponent of the Afghan policy of the conservative government.

Parliamentary candidate

In 1880 he and John Morley unsuccessfully contested Westminster in the liberal interest against Sir Charles Russell, and W. H. Smith. Hobhouse was at the bottom of the poll.[1]

Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

Summarize

Perspective

In 1878 Hobhouse was made arbitrator under the Epping Forest Act and in 1881 he succeeded Sir Joseph Napier on the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. There without salary he did useful judicial work for twenty years. He delivered the decision of the committee in 200 appeals, of which 120 were from India. Several cases were of grave moment. In Merriman v. Williams (7 Appeal Cases 484), an action between the bishop and dean of Grahamstown, Hobhouse set forth fully the history of the relationship of the Anglican Church of Southern Africa with the Church of England, and decided that the South African Church is independent of it. In the consolidated appeals in 1887 by several Canadian banks (12 Appeal Cases, 575) against the decisions of the Court of Queen's Bench for Quebec, which involved the respective limits of the power of the dominion and provincial legislatures to regulate banks, Hobhouse's judgment upheld the right of the province to tax banks and insurance companies constituted by Act of the dominion legislature. In a case from India in 1899 (26 Indian Appeals, Law Reports 113) which necessitated the review of a number of conflicting decisions of the Indian courts, Hobhouse settled a long disputed point in Hindu law and decided, contrary to much tradition, that when an individual person was adopted as an only son, the also gave the judgment of the Privy Council in Grey v Manitoba Railway Co [1897] UKPC 1897_8, [1897] AC 254.

House of Lords

In 1885 Hobhouse accepted a peerage as Baron Hobhouse, of Hadspen in the County of Somerset,[2] with a view to assisting in the judicial work of the House of Lords, but a statutory qualification by which only judges of the high courts of the United Kingdom could sit to hear appeals had been overlooked. In 1887 the disqualification was removed by Act of Parliament in regard to members of the Judicial Committee; but Hobhouse did not take up the work of a judge in the House of Lords. He only sat there to try three cases, in two of which, Russell v. Countess of Russell (1897 Appeal Cases 395) and the Kempton Park case (1899 Appeal Cases 143), he was in a dissenting minority. As a judge Hobhouse, who was always careful and painstaking, invariably stated the various arguments fully and fairly, but he was tenacious of his deliberately formed opinion.[1]

London government

While engaged on the Judicial Committee, Hobhouse devoted much energy to local government of London. From 1877 to 1899 he was a vestryman of St George's, Hanover Square. In 1880 he assisted to form and long worked for the London Municipal Reform League, which aimed at securing a single government for the metropolis. From 1882 to 1884 he was a member of the London School Board. Upon the creation of the London County Council in 1888 Hobhouse was one of the first aldermen.[1]

Personal life

Lord Hobhouse married, on 10 August 1848, the campaigner Mary Ferrer (died 1905), daughter of Thomas Farrer, solicitor, and sister of Thomas Farrer, 1st Baron Farrer, Sir William Farrer (died 1911), and Cecilia Frances (died 1910), wife of Stafford Northcote, 1st Earl of Iddesleigh. Advancing years and increasing deafness led him to retire from the Judicial Committee in 1901. He died at his London residence, 15 Bruton Street, Mayfair, on 6 December 1904, and was cremated at Golders Green. He left no issue, and the peerage became extinct on his death.[1]

He acted as guardian to his nephew Henry Hobhouse after the death of Henry's father in 1862.[3] Henry's grandson John Hobhouse, Baron Hobhouse of Woodborough was a judge and law lord.[4]

Appreciation and publications

To the last an advanced liberal and constructive legal reformer, Hobhouse, all of whose judicial work was done gratuitously, urged many legal changes, which won adoption very slowly. Much influence is assignable to an address by him before the Social Science Congress at Birmingham in 1868 on the law relating to the property of married women (1869; new edition 1870), and to The Dead Hand (1880), a collection of addresses on endowments and settlements of property (reprinted from the Transactions of the Social Science Association).[1]

- Hobhouse, Arthur (1870). . Manchester: A. Ireland & Co.

Arms

|

|

References

Notes

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.