James Fitzjames Stephen

English lawyer, judge, writer, and philosopher (1829–1894) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Sir James Fitzjames Stephen, 1st Baronet, KCSI (3 March 1829 – 11 March 1894) was an English lawyer, judge, writer, and philosopher. One of the most famous critics of John Stuart Mill, Stephen achieved prominence as a philosopher, law reformer, and writer.

Sir James Fitzjames Stephen | |

|---|---|

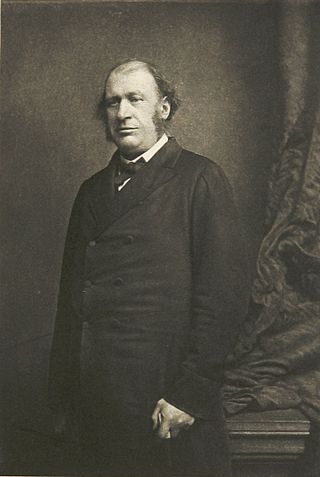

James Fitzjames Stephen, by Bassano, 1886 | |

| Judge of the High Court | |

| In office 1879–1891 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 3 March 1829 Kensington, London, England |

| Died | 11 March 1894 (aged 65) Red House Park Nursing Home, Ipswich, Suffolk, England |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse | Mary Richenda Cunningham |

| Children | 7, including Katharine Stephen |

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | King's College, London Trinity College, Cambridge University of London |

| Occupation | Queen's Counsel, Legal member of the Council of India, judge |

Early life and education, 1829–1854

Summarize

Perspective

James Fitzjames Stephen was born on 3 March 1829 at Kensington Gore, London, the third child and second son of Sir James Stephen and Jane Catherine Venn. Stephen came from a distinguished family. His father, the drafter of the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, was Permanent Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies and Regius Professor of Modern History at Cambridge. His grandfather James Stephen and uncle George Stephen were both leading anti-slavery campaigners. His younger brother was the author and critic Sir Leslie Stephen, whilst his younger sister Caroline Stephen was a philanthropist and a writer on Quakerism. Through his brother Leslie Stephen, he was the uncle of Virginia Woolf. He was also a cousin of the jurist A. V. Dicey.

Stephen was first educated at the Reverend Benjamin Guest's school in Brighton from the age of seven, before spending three years at Eton College from 1842. Strongly disliking Eton, Stephen completed his pre-university education by attending King's College, London for two years.

In October 1847 he entered Trinity College, Cambridge.[1] Although an outstanding intellect, he took an undistinguished BA in Classics in 1851, being, in his own words, one of the "most unteachable of human beings". He was, however, well-known as a strong debater at the Cambridge Union. He was also elected to the exclusive Cambridge Apostles, his proposer being Henry Maine, the newly appointed Regius Professor of Civil Law, who became a lifelong friend despite their differing temperaments. At Apostles meetings, he frequently sparred with William Harcourt, later leader of the Liberal Party, in debates described by contemporaries as "veritable battles of the gods". Another Apostles contemporary was the physicist James Clerk Maxwell.

Being conscious of the slightness of his legal education, he then read for an LL.B. from the University of London.[2] This was an unusual step for its day, and it was there that he first seriously engaged with the works of Jeremy Bentham.

Early career, 1854–1869

Summarize

Perspective

After leaving Cambridge, Stephen chose to enter a legal career, though his father had hoped for a clerical career. He was called to the bar in January 1854 by the Inner Temple, and joined the Midland Circuit.[3] His own estimation of his professional success—written in later years—was that in spite of such training rather than because of it, he became a moderately successful advocate and a rather distinguished judge.

In his earlier years at the bar he supplemented his income from a successful but modest practice as a journalist. He contributed to the Saturday Review from the time it was founded in 1855. He was in company with Maine, Harcourt, G. S. Venables, Charles Bowen, E. A. Freeman, Goldwin Smith and others. Both the first and the last books published by Stephen were selections from his papers in the Saturday Review (Essays by a Barrister, 1862, anonymous; Horae sabbaticae, 1892). These volumes embodied the results of his studies of publicists and theologians, chiefly English, from the 17th century onwards. He never professed his essays to be more than the occasional products of an amateur's leisure, but they were well received.

From 1858 to 1861, Stephen served as secretary to a Royal Commission on popular education, whose conclusions were promptly put into effect. In 1859 he was appointed Recorder of Newark. In 1863 he published his General View of the Criminal Law of England,[4] the first attempt made since William Blackstone to explain the principles of English law and justice in a literary form, and it enjoyed considerable success. The foundation of the Pall Mall Gazette in 1865 gave Stephen a new literary avenue. He continued to contribute until he became a judge.

Stephen's practice at the Bar was an uneven one, though he appeared in two notable cases. In 1861–62, he unsuccessfully defended the Reverend Rowland Williams in the Court of Arches against charges of heresy, though he was ultimately acquitted in the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. In 1865–66, Stephen was retained (along with Edward James QC) by the Jamaica Committee, which sought to prosecute Edward Eyre, Governor of Jamaica, for his excesses in suppressing the Morant Bay rebellion of 1865. They produced a legal opinion, which charged Eyre and his officers with serious breaches of English criminal law, some of them capital.

In early 1867, Stephen was retained by the Jamaica Committee to prosecute Alexander Abercromby Nelson and Herbert Brand, two military officers who had sat on the court martial which sentenced George William Gordon to death; but the grand jury declined to return a true bill. He was then retained to prosecute Eyre: when he began his case, Stephen surprised observers by praising Eyre as a courageous man who had acted honourably in an emergency. Eyre was discharged and Stephen fell out with the Jamaica Committee. His friendship with John Stuart Mill, who was a leading member of the Committee, was permanently damaged. Stephen was a critic of Mill's "sentimental liberalism", arguing that the British government was justified in applying force to prevent subject societies from descending into anarchy.[5]

Meanwhile, Stephen's legal career proceeded apace, and in 1868, he became a Queen's Counsel, one of fifteen that year. However, he suffered a setback in January 1869, when he was passed over for the Whewell Professorship of International Law in favour of his old rival William Harcourt.

Stephen in India, 1869–1872

Summarize

Perspective

The decisive point of Stephen's career was in the summer of 1869, when he accepted the post of legal member of the Viceroy's Executive Council in India. His appointment was at the recommendation of his friend Henry Maine, who was his immediate predecessor. He arrived in India in December 1869. During his time in India, Stephen would draft twelve acts and eight other enactments, most of which are still in force.

Guided by Maine's comprehensive talents, the government of India had entered a period of systematic legislation which was to last about twenty years. Stephen had the task of continuing this work by conducting the Bills through the Legislative Council. The Native Marriages Act of 1872 was the result of deep consideration on both Maine's and Stephen's part. The Indian Contract Act had been framed in England by a learned commission, and the draft was materially altered in Stephen's hands before, also in 1872, it became law.

Indian Evidence Act

The Indian Evidence Act of the same year, entirely Stephen's own work, made the rules of evidence uniform for all residents of India, regardless of caste, social position, or religion. Besides drafting legislation, at this time Stephen had to attend to the current administrative business of his department, and he took a full share in the general deliberations of the viceroy's council. His last official act in India was the publication of a minute on the administration of justice which pointed the way to reforms not yet fully realized, and is still a valuable tool for anyone wishing to understand the judicial system of British India.

Return to England, 1872–1879

Summarize

Perspective

Stephen returned, mainly for family reasons, to England in the spring of 1872. During the voyage he wrote a series of articles which resulted in his book Liberty, Equality, Fraternity (1873–1874)--a protest against John Stuart Mill's neo-utilitarianism. Around this time, Leslie Stephen noted the influence of Thomas Carlyle on his brother's thought.[6] This showed in Stephen's famous attack on the thesis of John Stuart Mill's essay On Liberty, arguing for legal compulsion, coercion and restraint in the interests of morality and religion.[7][8] Stephen argued, "Force is an absolutely essential element of all law whatever."[5]

Fitzjames Stephen stood in an 1873 by-election as a Liberal for Dundee, but came in last place. The same year, he was elected to the Metaphysical Society; he gave seven papers to the Society, making him one of its most active members. In 1875, he was appointed Professor of Common Law at the Inns of Court. He also sat on government commissions on fugitive slaves (1876), extradition (1878), and copyright (1878). He also appeared irregularly as counsel in the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.

Experience in India gave Stephen opportunity for his next activity. The government of India had been driven by the conditions of the Indian judicial system to recast a considerable part of the English law which had been informally imported. Criminal law procedure, and a good deal of commercial law, had been or were being put into easily understood language, intelligible to civilian magistrates. The rational substance of the law was preserved, while disorder and excessive technicalities were removed. Using Jeremy Bentham's ideal of codification, he attempted to get the same principles put into practice in the United Kingdom. As a preparatory step, Stephen also privately published digests in code form of the law of evidence (1876) and criminal law (1877).

In August 1877, Stephen's proposals were taken up by the government and he was asked to draft a criminal code for England. He completed his draft in early 1878 and it was debated in Parliament, after which it was referred to a Royal Commission under the chairmanship of Lord Blackburn, with Stephen as a member. In 1879, the Commission produced a draft bill, which received opposition from many quarters. It did, however, serve as the basis of the criminal codes of many parts of the British Empire, including those of Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

Judicial career and final years, 1879–1894

Summarize

Perspective

After his return from India, Stephen had sought a judgeship for both professional and financial reasons. In 1873, 1877, and 1878, he went on circuit as a commissioner of assize. In 1878 he was considered, but not selected, as Recorder of London in succession to Russell Gurney. In 1873, he had also been proposed as Solicitor-General by Sir John Coleridge, the Attorney-General, though Sir Henry James was chosen instead.

When Stephen was charged with the preparation of the English criminal code, he was virtually promised a judgeship, though no explicit promise could be made. Finally, in January 1879, Stephen was appointed a Justice of the High Court, in succession to Sir Anthony Cleasby. He was initially assigned to the Exchequer Division. When that division was merged into the Queen's Bench Division in 1881, Stephen was transferred to the latter, where he remained until his retirement. Occupied with the preparation of the criminal code, he only made his first appearance as a judge in April 1879 at the Old Bailey, when he passed a death sentence against a matricide.

Distracted by his literary and intellectual pursuits, his time as a judge was unimpressive relative to the rest of his career, though his judgments were of a high quality. He had transient hopes of an Evidence Act being brought before Parliament, and in 1878 the Digest of Criminal Law became a Ministerial Bill with the cooperation of Sir John Holker, who was Attorney-General in the second government of Benjamin Disraeli. The Bill was referred to a judicial commission, which included Stephen, but ultimately failed, and was revised and reintroduced in 1879 and again in 1880. It dealt with procedure as well as substantive law, and provided for a court of criminal appeal, though after several years of judicial experience Stephen changed his mind as to the wisdom of this course.[citation needed] However, no substantial progress was made during any sessions of Parliament. In 1883 the part relating to procedure was brought in separately by Gladstone's law officer Sir Henry James, and went to the grand committee on law, which found that there was insufficient time to deal with it satisfactorily in the course of the session.

Stephen's final years were undermined first by physical and then steady mental decline. In 1885, he had his first stroke. Despite accusations of unfairness and bias regarding the murder trials of Israel Lipski in 1887 and Florence Maybrick in 1889, Stephen continued performing his judicial duties. However, by early 1891 his declining capacity to exercise judicial functions had become a matter of public discussion and press comment, and following medical advice Stephen resigned in April of that year, whereupon he was made a baronet.[3] Even during his final days on the bench, Stephen is reported to have been 'brief, terse and to the point, and as lucid as in the old days'. Having lost his intellectual power, however, 'as the hours wore on his voice dropped almost to a whisper'.[9]

Stephen died of chronic renal failure on 11 March 1894 at Red House Park, a nursing home near Ipswich, and was buried at Kensal Green Cemetery, London.[10] His wife survived him.

Honours

Stephen was knighted as a Knight Commander of the Order of the Star of India (KCSI) in January 1877. He was created a Baronet, of De Vere Gardens in the parish of Saint Mary Abbott, Kensington, in the County of London, on 29 June 1891, shortly after his resignation from the bench. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, a corresponding member of the Institut de France (1888). He received honorary doctorates from the University of Oxford (1878) and the University of Edinburgh University (1884), and was elected an honorary fellowship of Trinity College, Cambridge (1885).

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Criminal appeal was discussed and an Act passed in 1907; otherwise nothing has been done in the UK with either part of the draft code since. The historical materials which Stephen had long been collecting took permanent shape in 1883 as his History of the Criminal Law of England. He lacked time for a planned Digest of the Law of Contract (which would have been much fuller than the Indian Code). Thus none of Stephen's own plans of English codification took effect. The Parliament of Canada used a version of Stephen's Draft Bill revised and augmented by George Burbidge, at the time Judge of the Exchequer Court of Canada, to codify its criminal law in 1892 as the Criminal Code, 1892. New Zealand followed with the New Zealand Criminal Code Act 1893 and a number of Australian colonies adopted their own versions as Criminal Codes in following years

His book Liberty, Equality, Fraternity was called the "finest exposition of conservative thought in the latter half of the 19th century" by Ernest Barker.[11] It was listed as one of Ten Conservative Books to read in the chapter of that name in The Politics of Prudence by Russell Kirk. According to Princeton University political theorist Greg Conti, Stephen's political thought had liberal characteristics, even though he has frequently been characterized as conservative or religious authoritarian.[12] According to Conti, Stephen "articulated robustly both technocratic and pluralistic visions of politics. Perhaps more stridently than any Victorian, he put forward an argument for the necessity and legitimacy of expert rule against claims for popular government. Yet he also insisted on the plurality of perspectives on public affairs and on the ineluctable conflict between them."[12]

The 1957 Wolfenden report recommended the decriminalisation of homosexuality and this sparked off the Hart-Devlin debate on the relationship between politics and morals. Lord Devlin's 1959 critique of the Wolfenden report (titled The Enforcement of Morals) resembled Stephen's arguments, although Devlin had arrived at his opinions independently, having never read Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.[13] Hart claimed that "though a century divides these two legal writers, the similarity in the general tone and sometimes in the detail of their arguments is very great".[13][14] Afterwards, Devlin tried to obtain a copy of Liberty, Equality, Fraternity from his local library but could only do so with "great difficulty"; the copy, when it arrived, was "held together with an elastic band".[13][15] Hart, an opponent of Stephen's views, regarded Liberty, Equality, Fraternity as "sombre and impressive".[16][14]

An eleven-volume set of his collected writings (2013 - ) is currently[when?] being prepared for Oxford University Press by the Editorial Institute at Boston University.

Personal life

Stephen married Mary Richenda Cunningham, daughter of John William Cunningham,[17] on 19 September 1855. They had three sons and at least four daughters surviving to adulthood, but only one grandchild:

- Katharine Stephen (1856–1924), librarian and Principal of Newnham College, Cambridge;

- Sir Herbert Stephen, 2nd Baronet (1857–1932), barrister and clerk of assize, who succeeded him in the baronetcy;

- James Kenneth Stephen (1859–1892), poet and tutor to Prince Albert Victor, who predeceased his father;

- Sir Harry Lushington Stephen, 3rd Baronet (1860–1945), Judge of the High Court of Calcutta, 1901–1914,[3] who succeeded his eldest brother as the 3rd baronet;

- Helen Stephen (1862–1908);

- Rosamond Emily Stephen (1868–1951), lay missionary in the Church of Ireland in Belfast and advocate of ecumenism;

- Dorothea Jane Stephen (1871–1965), teacher of religion in India.

Quotations

"Some men, probably, abstain from murder because they fear that, if they committed murder, they would be hung. Hundreds of thousands abstain from it because they regard it with horror. One great reason why they regard it with horror is, that murderers are hung with the hearty approbation of all reasonable men".[18]

On evidence obtained by duress or torture:

"It is far pleasanter to sit comfortably in the shade rubbing red pepper in some poor devil's eyes, than to go about in the sun hunting up evidence."[19]

Arms

|

|

Works

- Essays by a Barrister. London: Elder and Co., 1862.

- A General View of the Criminal Law of England. London: Macmillan & Co., 1890 (1st Pub. 1863).

- The Indian evidence act (I. of 1872): With an Introduction on the Principles of Judicial Evidence. London: Macmillan and Co., 1872.

- Liberty, Equality, Fraternity. New York: Holt & Williams, 1873 (2nd ed.) 1874.

- A History of the Criminal Law of England, Vol. 2, Vol. 3. London: Macmillan & Co., 1883.

- The Story of Nuncomar and the Impeachment of Sir Elijah Impey, Vol. 2. London: Macmillan and Co., 1885.

- Horae Sabbaticae: Reprint of Articles Contributed to the Saturday Review. First Series. London: Macmillan & Co., 1892.

- Horae Sabbaticae: Reprint of Articles Contributed to the Saturday Review. Second Series. London: Macmillan & Co., 1892.

- Horae Sabbaticae: Reprint of Articles Contributed to the Saturday Review. Third Series. London: Macmillan & Co., 1892.

Selected articles

- "Responsibility and Mental Competence," Transactions of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science, 1865.

- "Codification in India and England," The Fortnightly Review, Vol. XVIII, 1872.

- "Parliamentary Government," Part II, The Contemporary Review, Vol. XXIII, December 1873/May 1874.

- "Caesarism and Ultramontanism,"[21] Part II, The Contemporary Review, Vol. XXIII, December 1873/May 1874.

- "Necessary Truth," The Contemporary Review, Vol. XXV, December 1874/May 1875.

- "The Laws of England as to the Expression of Religious Opinion," The Contemporary Review, Vol. XXV, December 1874/May 1875.

- "Mr. Gladstone and Sir George Lewis on Authority in Matters of Opinion," The Nineteenth Century, March/July, 1877.

- "Improvement of the Law by Private Enterprise," The Nineteenth Century, Vol. II, August/December, 1877.

- "Suggestions as to the Reform of the Criminal Law," The Nineteenth Century, Vol. II, August/December, 1877.

- "The Influence Upon Morality of a Decline in Religious Belief." In: A Modern Symposium, Rose-Belford Publishing Co., 1878.

- "Gambling and the Law," The Nineteenth Century, Vol. XXX, July/December, 1891.

- "Criminal Procedure from the Thirteenth to the Eighteenth Century." In: Select Essays in Anglo-American Legal History, Vol. II, Little, Brown & Company, 1908.

Miscellany

- "Codification in India and England," Opening Address of the Session 1872-3 of the Law Amendment Society, The Law Magazine, Vol. I, New Series, 1872.

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.