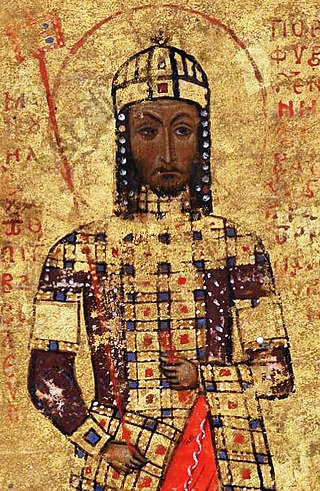

曼努埃爾一世 (拜占庭)

拜占庭帝國科穆寧王朝皇帝 来自维基百科,自由的百科全书

曼努埃爾一世(希臘語:Μανουήλ Α' ο Κομνηνός,1118年11月28日—1180年9月24日),是十二世紀的東羅馬皇帝。此時,東羅馬帝國和地中海歷史迎來一個關鍵的轉折點。在其統治期間,科穆寧王朝經歷最後一次興盛,帝國的軍事與經濟實力得以恢復,文化也走向繁榮。

此條目翻譯自其他語言維基百科,需要相關領域的編者協助校對翻譯。 |

東羅馬帝國曾經是地中海世界的掌控者,為復興這一榮耀,曼努埃爾採取雄心勃勃的對外政策。在這個過程中,它同教宗哈德良四世以及復興中的西方世界結盟,並對西西里王國發動入侵試圖收復南義大利,但沒有成功。在第二次十字軍東征期間,他使帝國躲避十字軍帶來的威脅,並使他們順利通過。曼努埃爾還將十字軍國家納入自己的保護之下。面對穆斯林對聖地的侵襲,他促使帝國與耶路撒冷王國聯合進攻法蒂瑪王朝。曼努埃爾重塑帝國在巴爾幹和東地中海地區的版圖,並將匈牙利和十字軍諸國納入東羅馬帝國的勢力範圍之下。此外,他還對帝國東西面鄰國們持續發動富有侵略性的戰爭。

然而,在經歷密列奧塞法隆戰役的慘敗後,曼努埃爾一世被迫採取妥協政策,使其在東方地區的成就功虧一簣,這一失敗很大程度上是由於他以傲慢自大用兵方式進攻處在有利位置的羅姆蘇丹國軍隊。儘管東羅馬帝國軍隊在門德雷斯河谷戰役挽回損失,並且曼努埃爾與蘇丹基利傑阿爾斯蘭二世締結一份對帝國有利的和約,但密列奧塞法隆戰役最終表明帝國為從突厥人手中收復安納托利亞地區的努力沒有成功。

曼努埃爾被希臘人譽為大帝,因為人們願意向其效忠而聲名遠播。在其大臣約翰·金納莫斯的歷史作品裡,曼努埃爾不僅是一代英傑,也是美德的典範。十字軍諸國在與曼努埃爾的聯繫中也受到他影響,他在西方天主教世界一些地區享有「最受上帝祝福的君士坦丁堡皇帝」(the most blessed emperor of Constantinople)稱號。[1] 然而,現代歷史學家卻對他缺乏熱情。他們中的一些人認為,曼努埃爾所掌握的強權並非完全是他個人成就,而是來源於科穆寧王朝的強盛。此外,曼努埃爾去世後,帝國的國力嚴重衰退,與其統治期間的一些問題不無關聯。[2]

繼承皇位

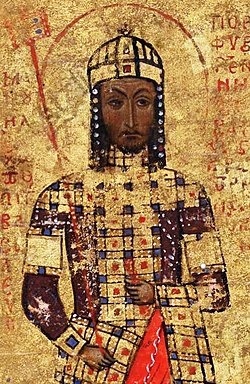

約翰二世之死與曼努埃爾一世的即位,13世紀推爾的威廉歷史手稿。現藏於法國國家圖書館。

曼努埃爾·科穆寧是約翰二世與皇后匈牙利的伊琳娜第四子(幼子),所以他似乎不可能繼承皇位。他的外祖父是匈牙利國王聖拉斯洛一世。因為曼努埃爾在他父親對抗塞爾柱突厥人的戰爭中表現卓越,亦或是其它原因,所以1143年他被臨終的約翰二世選為繼承人,而不是他脾氣易怒的兄長伊薩克·科穆寧。1143年4月8日約翰二世去世後,曼努埃爾被軍隊擁立為皇帝。[3]然而曼努埃爾的繼位並非四平八穩,他的父親死在遠離君士坦丁堡的奇里乞亞荒野,他認為應該儘快返回首都。但他仍然要處理好他父親的葬禮,還要按照傳統在他父親去世的地方組織建立一座修道院。他立即派父親的摯友,大統領約翰·阿克蘇赫在他之前前往首都,去逮捕他最危險的潛在競爭對手——他的兄長伊薩克,因為伊薩克正居住在大皇宮,並且可以立即掌控皇帝登基的禮服與大量財富。阿克蘇赫在皇帝去世的消息傳到首都之前便抵達,他迅速確保首都對曼努埃爾的忠誠,曼努埃爾於1143年8月進入首都。之後他被新任命的宗主教米海爾二世所加冕。幾天後,在確保皇位不會有更多的威脅後,曼努埃爾下令釋放伊薩克。[4]然後他下令贈予君士坦丁堡每一位戶主兩個金幣,並且為教會捐贈200磅黃金(包括每年捐贈200枚銀幣)。[5]

曼努埃爾從他父親那裡繼承下來的帝國,同八個世紀之前君士坦丁大帝的帝國相比,已經有巨大的變化。在他的前輩查士丁尼一世時代,部分屬於西羅馬帝國的領土包括義大利、北非和部分西班牙都被收復。然而在七世紀,帝國發生劇變,國力也急劇衰弱:阿拉伯帝國從帝國手中奪取埃及、巴勒斯坦和敘利亞大部。之後,他們又向西席捲在君士坦斯二世時代還是帝國西部行省的北非與西班牙。此後的幾百年間,皇帝們統治主要領域包括東方的小亞細亞大部和西方的巴爾幹地區。11世紀晚期,拜占庭帝國走向軍事與政治的衰退期,儘管帝國的衰落已經在曼努埃爾祖父和父親統治下停滯,並很大程度上恢復原有的國力。但曼努埃爾所繼承的帝國依然要面對著一系列艱巨挑戰:11世紀末期,諾曼人從拜占庭皇帝的手裡奪取南義大利。塞爾柱突厥人也奪取安納托利亞。在黎凡特,十字軍諸國這一新勢力的出現為帝國帶來新挑戰。同此前幾個世紀的任何時候相比,曼努埃爾所面臨的困難都要更為艱巨。[6]

對外

1135年第一次十字軍東征與第二次十字軍東征之間的近東局勢。拜占庭帝國,埃德薩伯國與其他十字軍諸國,穆斯林塞爾柱帝國、法蒂瑪王朝並立。

1144年,曼努埃爾迎來他政治生涯中的第一次考驗,面對安條克親王普瓦捷的雷蒙對奇里乞亞領土轉讓的要求。然而第二年,十字軍國家之一的埃德薩伯國被伊瑪德丁·贊吉領導下的贊吉王朝發動的伊斯蘭吉哈德聖戰所滅亡。安條克東方側翼暴露在新的來自穆斯林的威脅之下,雷蒙立刻意識到向西方求援幾乎是不可能的,恥辱去拜訪君士坦丁堡幾乎是唯一的選擇。他收回以前的傲慢,踏上北上向拜占庭求援的旅途。在向曼努埃爾臣服之後,他的求援請求得到同意,但他必須要以宣誓向拜占庭效忠來擔保。[7]

1146年,曼努埃爾在軍事基地洛帕迪翁集結軍隊,並準備對羅姆蘇丹發動一場報復性的遠征,以懲罰突厥人屢次侵擾帝國安納托利亞及奇里乞亞的邊境。[8]因為沒有占領及奪取敵人領土的計劃,曼努埃爾的部隊在阿菲永卡拉希薩爾擊敗突厥人,並且帝國軍隊在攻取並摧毀設防城鎮菲羅梅隆前,釋放所有被突厥人俘虜的基督徒。[8]之後拜占庭軍隊到達羅姆蘇丹首都科尼亞,並劫掠其周邊地區,但拜占庭軍隊無法攻入城內。曼努埃爾此舉是為主動向西方展示拜占庭對十字軍國家的支持,凱納摩斯認為曼努埃爾此舉是為向自己新娘展示自己的卓越軍事才能。[9]當拜占庭在休戰時,曼努埃爾收到一封來自法國國王路易七世的信,信中稱:國王將率領一支軍隊去支援十字軍國家。[10]

十字軍第二次到達君士坦丁堡,Jean Fouquet繪製於1455-1460。

曼努埃爾在安納托利亞取得勝利後卻遇到阻礙,十字軍的到來,意味他必須返回巴爾幹。1147年,他得知由神聖羅馬帝國皇帝康拉德三世與法蘭西國王路易七世率領的兩支十字軍大軍正在穿越拜占庭領土。這時仍然有拜占庭皇室成員記得第一次十字軍東征時的情景,第一次十字軍東征是令曼努埃爾的姑姑安娜·科穆寧娜著迷屬於他祖父阿歷克塞那個時代的重要事件。[11]

許多希臘人懼怕十字軍,他們這麼認為是因為那些紀律鬆散的部隊在穿越拜占庭領土時,經常出現破壞公物和盜竊現象。因此拜占庭軍隊一直尾隨十字軍,試圖監督他們沿途的行為;更多拜占庭軍隊集結到君士坦丁堡,準備防禦任何對首都的侵犯。這一謹慎的行動經過深思熟慮,但十字軍在行軍過程中還是發生許多事端,這激發法蘭克人與希臘人之間的敵意;雙方互相責備,也導致曼努埃爾和他客人間的矛盾。曼努埃爾實施他祖父在第一次十字軍東征時沒有準備的防範措施——修補君士坦丁堡的城牆,並且他強迫兩位國王必須保證他領土的安全。康拉德的軍隊於1147年先進入拜占庭帝國領土,在拜占庭史料中他們被描述的更為突出,暗示他們比法軍更麻煩。[a]當時的拜占庭歷史學家凱納摩斯描述康拉德軍隊與拜占庭軍隊在君士坦丁堡城牆外發生一場全面的衝突。最終拜占庭軍隊擊敗德意志十字軍,這迫使十字軍打消進入君士坦丁堡的念頭,並迫使康拉德同意帶領他的軍隊加速渡過博斯普魯斯海峽,前往亞洲沿岸的Damlis。[12][13]

然而在1147年後,雙方領袖之間的關係開始逐漸友善起來。1148年曼努埃爾機智的提出要與康拉德結為同盟,因為康拉德的貝莎早已經嫁給曼努埃爾;他最終說服康拉德與他共同對抗西西里的羅傑二世。[14]但十分不幸的是,康拉德在1152年便去世,儘管做了很大努力,曼努埃爾還是無法與康拉德的繼承人——腓特烈一世結為盟友。[b]

就十字軍問題曼努埃爾寫給教宗尤金三世的信,現存於梵蒂岡秘密檔案館。曼努埃爾在信中回復,前任教宗提示他法國國王路易七世將解放聖地並收復埃德薩伯國。曼努埃爾表示他願意接受法國軍隊並支持他們。但他抱怨他是從法王的使節手裡收到這封信,而不是教宗派來的大使。[15]

1156年,曼努埃爾的注意力再一次被轉移到安條克,新繼位的安條克親王沙蒂永的雷納德聲稱拜占廷皇帝違背要給予他一大筆錢的承諾,並且他還要進攻拜占廷的賽普勒斯島。[16]雷納德逮捕賽普勒斯的管理者、曼努埃爾的侄子約翰·科穆寧和米海爾·布拉納將軍。[17]拉丁歷史學家推爾的威廉在記載中很痛恨這場基督徒對抗基督徒的戰爭,並提及大量雷納德手下殘忍暴行的細節。[18]在洗劫整個島嶼,並掠走這裡所有的財富之後,雷納德的軍隊還在致殘那些倖存者之後,逼迫他們用極高價格買回他們所僅存的一點牧群。在搜刮足以使安條克富裕許多年的戰利品之後,入侵者們登上船隻駕船回國。[19]雷納德還將一些被致殘的人質送到君士坦丁堡,以作為他不順從皇帝的生動示範,並表達他對皇帝的蔑視。[17]

曼努埃爾採取有力方式來回應他對此事的憤怒。1158-1159年冬,他在他的龐大軍隊到達之前來到奇里乞亞;他急速推進(曼努埃爾只率領500騎兵在主力部隊的前方急速行軍)是為驚嚇奇里乞亞亞美尼亞王國的索羅斯二世,他們曾經參與十字軍對賽普勒斯的入侵。[20]索羅斯聞後,遂遁入群山之中,奇里乞亞便迅速落入曼努埃爾之手。[21]

與此同時,拜占庭軍隊推進的消息不久傳到安條克。在意識到自己完全沒有擊敗曼努埃爾的希望之後,雷納德也得知他不能從耶路撒冷國王鮑德溫三世那裡獲得任何援助。鮑德溫最初便不贊成雷納德進攻賽普勒斯,並且他已經與曼努埃爾達成協議。因此雷納德被他的盟友們拋棄並孤立,他知道屈辱投降是他唯一的希望。雷納德身穿麻布破衣、脖子上繫上吊繩,以此來祈求皇帝的寬恕。曼努埃爾最初無視撲倒在地的雷納德,並繼續和自己的朝臣聊天;推爾的威廉評論道,這一恥辱的情景持續很久,以至於在場所有的人都對他感到厭惡。[22]最終,曼努埃爾以雷納德宣誓成為帝國的附庸為條件原諒雷納德,實際上這就等於被迫將安條克的自主權交予拜占庭帝國。

1159年-1180年,拜占庭帝國保護下的安條克公國。

和平重新降臨,一場宏大的慶祝儀式於1159年4月12日為高奏凱歌的拜占庭軍隊進入安條克而舉行,曼努埃爾騎在飾滿皇帝標誌的高大坐騎上,耶路撒冷國王遠遠跟在他身後,安條克親王則在皇帝的鞍前馬後「忙扶著牽韁」。曼努埃爾免除對安條克市民的懲罰,並且為人們舉行競賽和馬上比武大會。5月,他又率領一支基督教聯軍開入前往埃德薩的征途。但曼努埃爾最終放棄進攻計劃,因為他收到敘利亞的統治者努爾丁釋放第二次十字軍東征戰役中被俘虜的6000名基督徒戰俘保證。[23]儘管這場遠征以輝煌的勝利告終,但現代學者認為曼努埃爾在恢復帝國事業上的成就,遠遠低於他所欲求的高度。[c]

在對自己的努力感到滿意之後,曼努埃爾返回君士坦丁堡。在他們返回的路上,他的軍隊被返回途中的突厥人所驚擾。儘管如此,拜占廷軍隊還是贏得勝利,他們在野外將突厥人擊潰,並使敵人損失巨大。在第二年,曼努埃爾將突厥人驅趕出伊蘇里亞。[24]

曼努埃爾發動遠征數十年前,1122年的南義大利局勢。

1147年,曼努埃爾迎戰西西里的羅傑二世,後者派兵奪取拜占庭的科孚島,並洗劫底比斯和科林斯。當時,這裡是希臘最富有的城市,也是拜占廷重要的絲綢紡織中心。羅傑二世同時將精通拜占廷絲綢紡織的工匠劫掠到巴勒莫,這裡新建立的諾曼絲綢工場急需他們。儘管庫曼人入侵巴爾幹地區分散曼努埃爾的注意力,但他還是在1148年與康拉德三世締結同盟,在威尼斯人的幫助下,拜占庭依靠威尼斯的強大艦隊,很快擊敗羅傑二世。1149年,曼努埃爾收復科孚島,並準備以此來進攻諾曼人的本土,這時羅傑二世也派安條克的喬治率領四十艘戰艦劫掠君士坦丁堡的郊區,喬治隨即戰死於君士坦丁堡附近。[25]曼努埃爾同意與康拉德共同入侵南義大利與西西里。與德意志人重新締結的同盟確定曼努埃爾其餘統治時期里對外政策的基本方向,儘管康拉德三世去世後,兩大帝國之間已經產生利益分歧。[14]

羅傑二世於1154年去世後,由威廉一世繼位,他將面對西西里和阿普利亞大批反對他統治的叛亂者,這也導致許多的阿普利亞難民投靠到拜占廷一方。康拉德三世的繼任者,腓特烈一世發動一系列對抗諾曼人的戰役,但他的遠征卻停滯不前。但這些動態鼓勵曼努埃爾趁機利用義大利半島上的動盪局勢。[26]1155年,他派出兩位獲得「至尊者」頭銜的米海爾·帕列奧略和約翰·杜卡斯二位將軍,率領拜占廷軍隊以及十艘船隻並攜帶大量的黃金去入侵阿普利亞。[27]二位將軍被指示去謀求腓特烈的援助,但腓特烈卻因為他的軍隊翻越阿爾卑斯山後士氣低落而拒絕。然而,在當地貴族(包括Loritello的伯爵羅伯特三世)的幫助下,曼努埃爾的遠征軍很快便在整個南義大利取得驚人成績,還聚集大批反對西西里王室以及威廉一世的叛亂者。[14]在武力的逼迫和金錢的誘惑下,許多的城堡放棄抵抗,遠征軍們取得輝煌的勝利。[23]

諾曼人到來之前,巴里在幾個世紀中都是拜占庭南義大利總督府的首府。它向拜占庭軍隊打開大門,欣喜若狂市民拆除諾曼人的堡壘。巴里陷落之後,特拉尼、焦維納佐、安德里亞、以及布林迪西也被攻占。威廉一世率領一支包括2000名騎士的軍隊趕來,但他卻受到重創。[28]

受到這些勝利的鼓舞之後,曼努埃爾夢想能夠恢復羅馬帝國,所以他無論如何都要使東正教與天主教重新合併,這一想法經常在談判與設想聯盟期間被提供給教宗。[29]如果能使東方和西方教會重新聯合,並且能夠永久與教宗和解,這次很可能是最佳的一次機會。並且除了被武力直接威脅時,教宗從未與諾曼人有過良好的關係。教宗更希望拜占庭帝國位於他的南部邊境,而不是時常處理與諾曼人各種各樣的麻煩。教宗哈德良四世對實現這種目標非常感興趣,並且這麼做也會大大增加他對所有東正教基督徒的影響力。曼努埃爾為教宗提供一大筆資金來為他的軍隊提供給養,同時他請求教宗將三座沿海城市的主權交與他,來換取拜占廷驅逐西西里的威廉協助。曼努埃爾還承諾會支付給教宗和聖座5000磅黃金。[30]談判很快便結束,曼努埃爾與哈德良四世締結同盟。[26]

教宗哈德良四世的畫像。

此時,就像戰爭有利於他的決策一樣,事態開始轉而對曼努埃爾不利。拜占庭軍隊指揮官米海爾·帕列奧略的行事態度令盟友離心離德,而且他還以伯爵羅伯特三世拒絕與他交談為由拖延起戰事來。儘管後來二人和解,但這削弱拜占庭軍隊作戰的勢頭:米海爾不久後便被召回君士坦丁堡,並且他的過失被認為是戰役失利主要原因。戰爭的轉折點發生在布林迪西戰役,西西里人從陸上和海上發動聯合進攻。當敵人迫近之時,那些已經被曼努埃爾用黃金僱傭來的僱傭兵突然要求大幅增加他們報酬。當這一要求被拒絕之時,他們就全都潰逃。甚至就連當地的貴族軍隊也開始逐漸撤離,不久後拜占廷軍隊指揮官約翰·杜卡斯便對寡不敵眾的情景感到絕望。[d]而趕到的阿歷克塞·布里恩尼奧斯與一些船隻也沒能挽回拜占庭軍隊的頹勢,海上戰鬥決定西西里人的勝利,約翰·杜卡斯與阿歷克塞·布里恩尼奧斯及四艘拜占廷船隻全都被諾曼人所俘獲。[31]曼努埃爾隨即便派遣阿萊克休斯·阿克蘇赫前往安科納去籌集另一支軍隊,但此時威廉一世已經奪回所有拜占廷在阿普利亞的占領區。布林迪西戰役的失敗,徹底終結拜占廷收復義大利的希望,這也表明拜占庭帝國在義大利的勢力相當虛弱,他們不是建立在軍事實力,而是建立在金錢與外交基礎之上的;1158年,拜占庭軍隊離開義大利,從此再也沒能返回。[32]這一時期主要的拜占廷歷史學家,包括卓尼亞鐵斯和凱納摩斯都認同阿克蘇赫從威廉一世那裡帶來的和約來讓曼努埃爾有尊嚴離開這場戰爭,儘管1156年一支由164艘船隻(攜有1萬餘人)的西西里軍隊已經對優比亞島與阿密拉羅斯發動一場毀滅性的洗劫。[33]

在義大利戰役期間和結束後,也是在聖座與腓特烈一世鬥爭期間,曼努埃爾極力去唆使教宗,暗示他東西方教會重新合併的可能。儘管1155年教宗哈德良四世表達他對教會重新合一的熱切希望,[e]他也希望延長與拜占庭的聯盟來對抗各種不可逾越問題。但教宗哈德良四世和他的繼任者們也需要獲得所有基督徒共同認同他們在宗教上的威望,並且他們還尋求這一威望超越拜占庭皇帝;並且他們也不希望完全依賴於皇帝或其他人。[29] 另一方面,曼努埃爾也希望得到一份官方上對他在東方和西方世俗世界上至高無上權威的認可。[34]然而這些條件任何一方也不能接受。儘管曼努埃爾這樣一位親西方的皇帝同意,帝國希臘公民們也會拒絕任何形式上的合併,就像三百多年後天主教會與東正教會在形式上統一在教宗名義之後一樣。儘管曼努埃爾對聖座以及所有的教宗,但他從未被教宗們授予「奧古斯都」的頭銜。並且儘管曼努埃爾為拉丁與希臘教會重新合併,兩次向教宗亞歷山大三世派出使者(1167和1169年),但教宗卻以教會聯合會帶來麻煩而拒絕。[35]最終,協議的具體內容顯得撲朔迷離,但兩大教會還是保持了分裂狀態。

義大利戰役的最終成果,從帝國所獲得利益上來看是有限的。安科納城成為拜占廷帝國在義大利的基地,並且承認皇帝作為他們的君主。諾曼人在受到打擊之後,現在開始與帝國為伍,在曼努埃爾統治其餘的時間裡,他們一直與帝國保持著和平。帝國實力在干預義大利事務的過程中被展現出來。然而,曼努埃爾在計劃中慷慨投入大量的資金,卻只獲得很少回報,並且在外交上處於孤立。曼努埃爾在義大利事務上必然花費一筆巨大的資金(可能超過2160000海培倫即30000金磅),然而這只產生很有限的收益。[36][37]

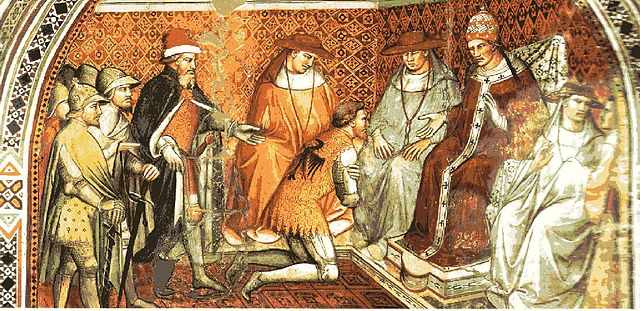

萊尼亞諾戰役戰敗後的腓特烈·巴巴羅薩覲見教宗亞歷山大三世。

1158年後,在新的條件之下,拜占庭政策的目標開始轉變。曼努埃爾決定反對霍亨斯陶芬王朝企圖使義大利承認腓特烈一世統治的目標。當腓特烈一世與北義大利邦國的戰爭開始時,曼努埃爾積極支持倫巴第聯盟,並予以經濟和人員、軍隊上援助。[38]被德意志人所毀壞的米蘭城牆,在拜占廷皇帝的資助下被重新修復。[39]1176年5月29日,腓特烈在萊尼亞諾戰役中被倫巴第人擊敗,似乎提高曼努埃爾在義大利的地位。根據愷納摩斯的記載,克雷莫納、帕維亞以及許多其他的利古里亞城市向曼努埃爾朝貢;[40]他的行動也顯著改善帝國與熱那亞和比薩之間關係,但不是威尼斯。1169年,他與熱那亞建立聯盟,次年又與比薩結盟。君士坦丁堡與威尼斯的關係越發緊張。1171年3月,曼努埃爾突然與威尼斯斷交,並且逮捕帝國全境內所有的兩萬多名威尼斯人,其貨物、船隻和商品均被沒收。[41]被激怒的威尼斯人派遣一直120艘船隻組成的艦隊去對抗拜占庭,並洗劫修斯島和萊博斯島。由於流行病的干擾以及150艘拜占庭戰艦的追擊,這支艦隊沒有取得任何重大勝利便被迫返回威尼斯。[42]談判拖延一些時日,但也沒有取得任何滿意的成果。在曼努埃爾剩餘的統治生涯中,拜占庭與威尼斯很可能再也沒能恢復友好的關係。[29]

在北部邊境,曼努埃爾極力維持馬其頓王朝皇帝們努力數百年收復而維持至今的疆域,有時候人們也覺得相對而言,那不算是最重要的地區。由於帝國在巴爾幹邊境的鄰國們分散曼努埃爾注意力,所以這阻攔他想要征服諾曼西西里王國的目標。1149年,拉西亞的塞爾維亞人在羅傑二世慫恿下,入侵拜占庭帝國的領土。自1129年後,帝國便與塞爾維亞以及匈牙利保持良好的關係,所以塞爾維亞的反叛令他感到震驚。 曼努埃爾迫使反叛的塞爾維亞人和他們領袖Uroš二世成為帝國附庸(1150-1152)。[43]之後他反覆襲擊匈牙利並希望能夠兼併他們在薩瓦河沿岸的領土。在1151-1153和1163-1168年的戰爭中,曼努埃爾率領他的軍隊組織規模宏大的攻勢深入匈牙利領土腹地,並獲得大量的戰利品。1167年,曼努埃爾派安德洛尼卡·康多提斯法諾斯率領15000軍隊對抗匈牙利人,並在米西烏姆戰役中取得決定性的勝利,[44]這使帝國在雙方議和使取得極大的優勢,匈牙利被迫割讓斯雷姆、波士尼亞和達爾馬提亞地區。1168年,幾乎整個亞得里亞海東岸都落入曼努埃爾的手中。[45]

曼努埃爾一世時期的海培論金幣,左側為耶穌基督像,右側為曼努埃爾。

曼努埃爾的努力也影響帝國同匈牙利之間外交關係。1164年,拜占庭皇帝與匈牙利國王簽訂協議,後者作出許多有利於拜占庭的許諾。伊什特萬三世的弟弟貝拉被承認為匈牙利王位繼承人,並將達爾馬提亞與克羅埃西亞地區封授給他。貝拉王子隨即被送到君士坦丁堡皇帝的宮廷中接受教育。曼努埃爾還打算把自己的長女瑪利亞許配給他,因此來確保匈牙利同帝國間的聯合。在宮廷中,貝拉改名為阿歷克塞並且獲得專制君主的頭銜,而這一頭銜此前只適用於皇帝本人,此後就被用作為一種地位上僅次於皇帝的特殊頭銜。由於曼努埃爾此前一直沒有合法男性後代,根據他的安排,貝拉可能將會繼承拜占庭皇位和匈牙利王位,從而成為兩國共同的君主,然而兩個意想不到的事件徹底改變現狀。1169年,曼努埃爾的第二任妻子安條克的瑪麗生下他的兒子,因此貝拉也就失去繼承拜占廷皇位的可能(儘管曼努埃爾宣布他不會放棄從匈牙利手中奪得的克羅埃西亞地區);1172年,史蒂芬三世無嗣而亡。貝拉回到了家鄉並繼承王位。在離開君士坦丁堡之前,他莊嚴的向曼努埃爾宣誓自己「將牢記皇帝與羅馬人的利益」。貝拉三世銘記著他的話:只要曼努埃爾還在世,他就不能取回他的克羅埃西亞繼承權,他只能以後再將這裡重新併入匈牙利。[45]

曼努埃爾試圖使俄羅斯諸公國加入他對抗匈牙利,並且也在次要程度上反諾曼西西里的外交網絡中。這使得俄羅斯諸王國們分化為親拜占庭和反拜占庭陣營。在12世紀40年代晚期,三位王公為爭奪俄羅斯的首腦地位而競爭:其中基輔大公伊賈斯拉夫二世同匈牙利的給扎二世聯繫並且對拜占庭懷有敵意;蘇茲達爾的尤里·格爾多魯基是曼努埃爾的盟友。加利西亞位於匈牙利邊疆北方和東北方,因此加利西亞在拜占庭和匈牙利的鬥爭中具有極大戰略意義。隨著伊賈斯拉夫和加利西亞的弗拉基米爾去世,局勢開始逆轉;曼努埃爾的盟友蘇茲達爾的尤里奪取基輔和雅羅斯拉夫爾,並成為加利西亞新的統治者,但他卻採取親匈牙利的立場。

1164-1165年,曼努埃爾的堂兄,未來的皇帝安德洛尼卡·科穆寧從拜占庭的監牢中逃出,並逃往加利西亞的雅羅斯拉夫爾宮廷。這個局面可能導致安德洛尼卡以加利西亞和匈牙利為支援宣稱並奪取曼努埃爾的皇位這一令人恐慌的前景,激使帝國陷入前所未有的外交恐慌之中。1165年,曼努埃爾饒恕安德洛尼卡,並且說服他返回君士坦丁堡。統治基輔的羅斯提斯拉夫接到一個任務,並且和帝國達成一份滿意的條約,他還承諾將向帝國提供輔助軍;加利西亞的雅羅斯拉夫也被說服同匈牙利斷交,並完全回到拜占庭的陣營。12世紀末期,加利西亞大公為帝國對抗庫曼人提供極為寶貴的援助。[46]

與加利西亞關係的恢復為曼努埃爾提供直接效益,1166年,他率領的兩支軍隊對匈牙利的東部省區發動一次巨大鉗形攻勢。一支軍隊穿越瓦拉幾亞平原,並翻越南喀爾巴阡山脈進入匈牙利,同時另一支軍隊借道加利西亞並進行一次巡遊,之後在加利西亞人的援助下,他們翻越喀爾巴阡山脈進入匈牙利境內。自從大部分匈牙利軍隊集結於西米烏姆和貝爾格勒邊境,他們便對拜占庭對特蘭西瓦尼亞的入侵缺乏防禦;這導致匈牙利的特蘭西瓦尼亞省區被拜占庭軍隊徹底破壞。[47]

阿馬爾里克一世與瑪利亞·科穆寧娜於1167年在推爾的婚禮。

控制埃及是耶路撒冷王國幾十年來的夢想,並且耶路撒冷國王阿馬爾里克一世對埃及軍事干預的政策,需要軍事和財政上的全力援助。[48]阿馬爾里克也知道如果他想追求控制埃及的夢想,他可能不得不離開安條克,尋求花費十萬第納爾去為博希蒙德三世贖身的曼努埃爾援助。[49][50]1159年,曼努埃爾的第一任皇后蘇爾茨巴赫的貝莎去世;1161年,曼努埃爾和阿瑪爾里克的表親安條克的瑪麗成婚。1165年,他派使者到君士坦丁堡的宮廷中向皇帝提出婚約。[51]1167年,在長達兩年的等待之後,阿瑪爾里克迎娶曼努埃爾侄孫女瑪利亞·科穆寧娜,並且「他立下和他的哥哥鮑德溫一樣的誓約」。[f]兩國正式結盟於1168年,兩國的領袖也為共同占領和瓜分埃及做好安排,曼努埃爾將會取得埃及沿海地區,阿馬爾里克則取得內陸。1169年秋,曼努埃爾派遣一支遠征軍同阿馬爾里克共同入侵埃及:一支拜占庭軍隊與一支由20艘大型戰艦、150艘戰艦以及60艘運輸船組成的艦隊在拜占廷海軍大將軍安德洛尼卡·康多提斯法諾斯的指揮下在阿什凱隆同阿馬爾里克會師。[51][52]在推爾的威廉記載中,聯軍中用於運輸騎兵的巨大運輸船給他非常留下深刻印象。[53]

儘管對一個遠離帝國核心區的國家發動一場如此遠距離進攻是可能是讓人感到意想不到的,如上一次是120多年前帝國試圖收復西西里但沒能成功,但這可以解釋曼努埃爾外交政策的目的——利用拉丁人去確保帝國的安全。從東地中海的全局或更遠的角度來看,曼努埃爾之所以會干涉埃及事務,是因為在十字軍諸國和伊斯蘭勢力在東方全面鬥爭的情況下,控制埃及將會是決定性因素。此後事實也證明,孱弱的穆斯林法蒂瑪王朝將是十字軍諸國命運關鍵所在。如果埃及擺脫隔離狀態並加入努爾丁旗下贊吉王朝領導的穆斯林聖戰勢力,十字軍將陷入巨大的災難之中。[48]

成功入侵埃及也會為拜占廷帝國贏得許多優勢。埃及是一個富饒的地區,在七世紀阿拉伯攻占前,埃及為君士坦丁堡提供大量的糧食。儘管其中的一部分不得不分享給十字軍,但帝國仍然可以從埃及獲得相當多的收入。再者,曼努埃爾可能也想要去鼓勵阿馬爾里克的計劃,不僅是為讓安條克從拉丁人的手中離開,而且加入這次軍事冒險也可以建立一個讓耶路撒冷國王繼續對曼努埃爾負債的新機會,這也將允許帝國去分享新取得的領土。[48]

曼努埃爾接見阿馬爾里克的使者及十字軍抵達Pelusium要塞。

1169年10月27日,拜占庭與十字軍聯軍包圍杜姆亞特,但由於十字軍和拜占庭軍隊合作的失敗,這次圍攻沒能成功。[54]拜占庭軍隊和阿馬爾里克都不想分享勝利的成果,戰事一直持續到拜占庭軍隊耗光糧食並且軍中出現饑荒時;阿馬爾里克對該城發動一場突襲,但他立即又終止行動,轉而與守城者尋求談判。另一方面,推爾的威廉記敘道希臘人並非完全沒有責任。[55]無論雙方指控的真相如何,當雨季來臨時,拉丁人和拜占庭軍隊都返回家鄉,然而半數的拜占庭軍隊都損失在突然來臨的暴風雨之中。[56]

儘管杜姆亞特之圍給阿馬爾里克不好的感受,但他仍然沒有放棄奪取埃及的夢想,他繼續尋求與拜占庭保持良好的關係,並希望他們加入另一場進攻,但這從來沒有實施過。[57]1171年,在埃及陷落於薩拉丁之後,阿馬爾里克親自來到君士坦丁堡。由此曼努埃爾得以為阿馬爾里克安排一場令他獲得榮譽的同時,彰顯他對帝國從屬的盛大歡迎儀式:在阿馬爾里克餘下的統治時間裡,耶路撒冷王國都是拜占庭的衛星國,曼努埃爾可以扮演聖地保護者的角色,向耶路撒冷王國施加越來越大的影響。[58]1177年,一支由150艘船隻組成的艦隊被曼努埃爾派去入侵埃及,但他們來到阿克後,卻由於伯爵佛蘭德斯的菲利普,許多耶路撒冷王國的顯貴們拒絕援助而返回。[59]

密列奧塞法隆戰役,這次戰役毀滅曼努埃爾占領科尼亞的最後希望。

1158年-1162年間,拜占庭對羅姆蘇丹發動的一系列戰役,使之達成對拜占庭帝國十分有利的和約。1161年,當羅姆蘇丹的蘇丹基利傑阿爾斯蘭二世前往君士坦丁堡尋求曼努埃爾的援助之時,皇帝在一份條約中正式接受蘇丹為義子,條約還規定羅姆蘇丹將歸還拜占庭帝國所有從達尼什曼德人手中奪走的土地。根據這份條約,包括西瓦斯在內的主要邊境地區,將由羅姆蘇丹以部分金錢為交換轉交於帝國手中,同時這也是為迫使蘇丹基利傑阿爾斯蘭二世承認曼努埃爾的霸權。[38][60] 後來當雙方都不打算遵守這一條約的意圖越發明顯之時,基利傑阿爾斯蘭二世隨即達成協約將自己的勢力擴展到達尼什曼德。曼努埃爾決定是時候一次性去解決突厥人的問題。[38][61][62]

因此,1176年,他集結整個拜占庭軍隊向羅姆蘇丹首都科尼亞進軍。[38]曼努埃爾的策略是以多利留姆與叟不萊昂作為進攻基地,以儘可能快的攻下科尼亞。[63]曼努埃爾的軍隊規模足足有三萬五千人,這支軍隊龐大而又笨拙。根據曼努埃爾寫給英國國王亨利二世的信中所述(曼努埃爾與亨利二世有極為頻繁的書信往來),軍隊行軍的隊列長達10英里(即16公里)長。[64]曼努埃爾經由老底嘉、高那、蘭佩、凱萊那、喬馬以及安條克向科尼亞進軍。就在通過密列奧塞法隆的入口之外,曼努埃爾接見羅姆蘇丹的使者,他們提出相當慷慨的條件向皇帝議和。然而軍中那些年輕好鬥的皇室成員勸告曼努埃爾趕快進攻,曼努埃爾竟然接受他們的建議並繼續進軍。[23]

曼努埃爾犯下一些嚴重的戰術失誤,比如他沒有派人前去偵察前方行軍道路是否安全。這些疏忽導致他直接將自己的大軍帶進敵人伏擊圈中。[65]1176年9月17日,曼努埃爾被基利傑阿爾斯蘭二世決定性在密列奧塞法隆擊敗,拜占庭軍隊在通過狹窄的山路時遭到伏擊。[38][66]拜占庭軍隊太過分散,並且他們被敵人團團包圍起來,[65]拜占庭軍隊的攻城器械也被迅速摧毀。之後曼努埃爾因為沒有攻城器械而被迫撤退,攻占科尼亞的計劃也成為泡影。曼努埃爾在戰役發生時便已經失去他的勇氣,他的精神也在極端自負與自貶中波動。[67]根據推爾的威廉記載,這是曼努埃爾唯一一次變得這樣。

基利傑阿爾斯蘭二世提出的議和條件是允許曼努埃爾和他的軍隊離開,但曼努埃爾需要拆除一些邊境堡壘,並將多利留姆與叟不萊昂邊境上的守軍撤出。然而,由於蘇丹沒能履行他在1162年承諾的約定,曼努埃爾只下令拆除叟不萊昂的防禦工事,而保留多利留姆的。[68]

但密列奧塞法隆戰役的戰敗,使得曼努埃爾及他的拜占庭帝國都陷入難堪窘境之中。自從105年之前的曼齊刻爾特戰役後,科穆寧王朝的皇帝們一直勤奮努力著,就是為恢復帝國以往在歐洲的聲望。然而由於曼努埃爾的過分自信,他向整個歐洲展示出拜占庭帝國仍然無法擊敗突厥人,儘管帝國在過去一個世紀裡已經有很大的進步。從曼努埃爾收到的神聖羅馬帝國皇帝腓特烈一世來信中,就可以看出這種損害有多麼嚴重。就曼努埃爾以拜占庭皇帝(羅馬皇帝)的身份而言,腓特烈一世以神聖羅馬帝國皇帝的身份稱曼努埃爾為希臘國王並要求向他臣服。[66]

密列奧塞法隆戰役常被描述為一場拜占庭軍隊全軍覆滅的慘敗,曼努埃爾自己也把這場戰役與曼齊刻爾特戰役的慘敗相提並論;在他看來,拜占庭倘若能在密列奧塞法隆戰役獲得勝利,便能洗刷曼齊刻爾特戰役戰敗所受的恥辱。事實上,儘管拜占庭帝國戰敗,但其軍隊的主要力量並沒有被大幅削弱。[66]因為絕大部分部隊傷亡都是右翼部隊所遭受的,而他們主要是由安條克的鮑德溫所指揮附庸國部隊所組成;同時還有大量的輜重車輛,因為他們是突厥人主要的攻擊目標。[69]拜占庭軍隊有限的損失很快就恢復,並且第二年帝國軍隊就擊敗來犯的羅姆蘇丹「精銳部隊」。[63]約翰·科穆寧·維塔斯被曼努埃爾命令去擊敗來犯的突厥部隊,他不僅從首都君士坦丁堡帶來一支部隊,並一直集結沿途部隊,這使得他在曼德爾河谷戰役中大勝突厥軍隊。[70]在取得勝利之後,曼努埃爾親率一支小部隊去驅趕從屈塔希亞以南巴納茲而來的突厥部隊。[68]但在1178年,一支拜占庭部隊在查拉克斯遭遇一支突厥部隊後便撤退,這讓突厥人劫掠許多牲畜。克勞狄奧波利斯與比提尼亞在1179年遭到突厥部隊圍攻,這又迫使曼努埃爾率領一支小的騎兵部隊去援救這兩座城市。到1180年,拜占庭帝國對羅姆蘇丹的戰事已經反敗為勝。[71]

持續不斷的戰事嚴重削弱曼努埃爾活力;他的健康迅速惡化,最終在1180年因傷寒去世。此外,如同曼齊刻爾特戰役,拜占庭帝國與羅姆蘇丹兩大勢力的平衡自此完全轉變——曼努埃爾再也沒能主動進攻羅姆蘇丹,在他去世後,突厥人開始越過邊境攻取拜占庭帝國剩餘的小亞細亞領土,並進一步向西遷移。

對內

曼努埃爾統治時期有三場主要的神學辯論。1156-1157年,基督為這個世界的罪將自己作為犧牲奉獻對象僅僅是聖父和聖靈,還是也包括「道」(即他自己)這個問題被提出。最後在君士坦丁堡的一場宗教會議中採取折中觀點,是基督肉體的犧牲給聖三位一體,[72]儘管安條克宗主教對此持有異議。

十年後,又一場論戰因基督所說「我的父親比我更偉大」而展開,這是屬於他的神性,還是他的人性,又或是兩者的聯合?[72]蘭佩的德米特里厄斯,一位剛剛從西方返回的拜占庭外交官,嘲諷西歐那裡對神學的理解,他們認為基督在人性上高於他的父親,但卻在神性上低於他。另一方面,曼努埃爾察覺到這或許是一個推動東西教會聯合的一個契機,他找到一個合情合理的方案,並在1166年3月2日所舉辦的宗教會議上得到多數支持並將此問題解決,在會議上他得到君士坦丁堡普世宗主教魯喀和未來的宗主教米海爾三世支持。[73]那些拒絕順從宗教會議研究決定的教士要麼財產被充公,要麼則被流放。[g]從政治層面上,這場論戰反映主要對皇帝教旨持反對意見的人是他外甥阿歷克塞·康多提斯法諾斯。[74]

第三個爭議湧現在1180年,當曼努埃爾對強制穆斯林改宗者進行莊嚴棄絕的誓詞表示反對之時。這個棄絕中最震撼咒詞其中一句是對穆罕默德和他追隨者所崇拜神明的直接反對:[75]

| “ | 並且首先,我詛咒穆罕默德的神,關於他穆罕默德說:「他是獨一的神,以堅固的,錘打出來金屬製成的神;他沒有生育,也沒有被生育,也沒有任何人與他相似。 | ” |

曼努埃爾代表拜占庭統治者中一種新的類型,他在與西方十字軍的接觸中也受到他們的影響。他安排騎士比武大會甚至還加入到其中。對於拜占庭人來說,這是一種不尋常且又讓他們感到不安的景象。由於生得一副好體格,曼努埃爾成為他所處時代拜占庭文獻資料的誇張對象,在其中庭他被呈現為一個具有極大個人勇氣的人。根據他的事跡,他就像是羅曼史中騎士精神的典範,例如他經常鍛鍊他手臂的肌肉庭以至於安條克的雷蒙德無法揮舞他所使用的長矛和盾牌。據說在一場著名的比武大會中,他騎著一匹火紅色的駿馬進入競技場,並且將兩名最健壯的義大利騎士打翻在地。據說他在一天裡親手殺死四十個突厥人,並且在對抗匈牙利人的戰役中,他獨自一人穿越橋梁在敵軍陣中,搶奪走敵人的旗幟。還有一次,他毫髮無損從一隊五百多名突厥人中殺出一條血路;在那之前他曾經在樹林中進行一次埋伏 ,隨同他的人只有他兄弟和阿克蘇赫。[76]

家庭成員

曼努埃爾與他的妻子安條克的瑪麗的畫像,現藏於羅馬的梵蒂岡宗座圖書館。

曼努埃爾有兩任妻子。他的第一任妻子蘇爾茨巴赫的貝莎與他在1146年完婚,她是康拉德三世的小姨子,去世於1159年。

他們有2個女兒:

1.瑪利亞·科穆寧娜(1152年–1182年),嫁給蒙費拉托的雷尼埃。

2.安娜·科穆寧娜(1154年-1158年)[77]

曼努埃爾的第二任妻子是安條克的瑪麗,她是雷蒙德與安條克的康斯坦斯之女,曼努埃爾與她於1161年結婚。瑪麗生下一個兒子:

曼努埃爾還有幾個私生子:

狄奧多拉·維塔斯娜所生:

- 阿歷克塞·科穆寧(出生於十二世紀六十年代早期),被皇帝承認為他的兒子,並在之後獲得「至尊者」的頭銜。他暫時與安德洛尼卡一世的私生女伊琳娜·科穆寧娜結婚。1183-1184年左右,他被他的岳父刺瞎雙眼。他至少活到1191年,而且卓尼亞鐵斯也知道他。[79]

瑪利亞·Taronitissa(有protovestiarios頭銜的約翰·科穆寧的妻子)所生,他們有一個被合法化的女兒:

- 瑪利亞·科穆寧娜,耶路撒冷王后。

二人的其他私生子:

1.阿歷克塞·科穆寧,獲得「侍臣(pinkernes)」頭銜,1184年逃出君士坦丁堡,並在諾曼人入侵並圍攻塞薩洛尼基時,成為他們的傀儡。

2.一個名字未知的女兒,她出生於1150年左右,並在1170年以前嫁給狄奧多拉·Maurozomes。她的兒子是曼努埃爾·Maurozomes,並且她的後代們統治羅姆蘇丹國。[80]

3.另一個名字未知的女兒,出生於1155年左右,她是作家迪米崔歐斯·Tornikes的外祖母。[81]

祖先:

| 曼努埃爾一世的祖先 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

評價

年輕時,曼努埃爾決心要通過武力來恢復拜占庭帝國在地中海國家間的主導地位。自1143年奇里乞亞野外那至關重要一天,他的父親宣布他為皇帝起,到他1180年去世時,已經過去37年之久。在這37年的歲月里,曼努埃爾同他所有的鄰國們都爆發過衝突。曼努埃爾的父親與祖父,在他之前一直為消除曼茲科特戰役帶來給帝國帶來的損傷而不懈工作著。由於他們的努力,曼努埃爾所繼承的帝國在組織性上比12世紀時帝國任何時期都要更好更強。然而很明顯曼努埃爾使用所有這些財產,但他增加多少還不清楚,而現在人們所懷疑他是否用這些資金取得最好的效果。[1]

| “ | 在曼努埃爾性格中最獨特特質是他的勤勉和怠惰,堅毅和柔弱的對立與更替。在戰爭中,他似乎對和平一無所知,在和平時,他好像沒有能力作戰。

——愛德華·吉本 |

” |

曼努埃爾證明自己是一位對所見到任何機會都保持精力充沛的一位皇帝,並且他樂觀心態塑造他的對外政策。然而他個人勇武只在很小的程度上實現他復興帝國的計劃。回溯往日,一些評論家已經批判曼努埃爾一些目標是不切實際的,尤其是他對埃及的遠征,證明他宏偉夢想是如此不可企及。他發動的規模最大戰役,是他為滅亡羅姆蘇丹發動的遠征,但卻以恥辱的戰敗而告終;當教宗亞歷山大三世接受與神聖羅馬帝國皇帝腓特烈一世的威尼斯協議起,他所做的最大外交努力也明顯失敗。該協議終止倫巴第同盟戰爭,促成教宗與腓特烈一世的和解。歷史學家馬克·C·巴圖西斯認為曼努埃爾和他的父親設法去重建一支國家軍隊,但他的改革並不足以滿足他雄心與需求;密列奧塞法隆戰役失敗暴露他政策根本上的弱點。在愛德華·吉本看來,曼努埃爾的勝利沒有產生任何長期或有效征服。[82] [83]

他對西方教會事務的顧問還包括比薩學者雨果·Eteriano。

卓尼亞鐵斯批判曼努埃爾的稅收政策,並指出曼努埃爾時代是一個揮霍無度的時代;卓尼亞鐵斯記載,被聚攏來的錢財都被揮霍在他臣民花費上。無論我們閱讀當時希臘人對他讚頌的資料,還是拉丁以及東方的資料,他們感想皆與卓尼亞鐵斯所描述的畫面一致:皇帝在所有方面上都鋪張過度,他很少為發展另一個領域而節省一個方面的花費。[24]曼努埃爾在陸軍、海軍、外交、典禮儀式、宮殿營建、科穆寧家族內部以及其他恩惠尋求者等方面都花銷巨大。這些數目巨大開支純粹是對帝國財政上的損失,就像那些湧入到義大利和十字軍諸國的特別津貼一樣,以及對1155-1156、1169以及1176年那些失敗的遠征事務上投入。[84]

曼努埃爾所取得成功一定程度上彌補他引發的問題,尤其在巴爾幹地區;為確保整個希臘和保加利亞的安全,曼努埃爾拓展帝國在巴爾幹的邊疆。這比他所有的行動都更為成功,他不僅控制東地中海以及亞得里亞海沿岸絕大部分肥沃的農田,而且還掌控這一地區的全部貿易活動。儘管它沒有實現他的雄偉目標,但他對匈牙利的戰爭使他控制達爾馬提亞沿海地區,西米烏姆地區富饒的農業產業,以及從匈牙利到黑海的多瑙河貿易路線。據說他對巴爾幹的遠征掠奪大量戰利品、奴隸以及牲畜。[85]凱納摩斯對1167年的戰役後從戰死的匈牙利人繳獲大量武器留下深刻印象。[86]儘管曼努埃爾對突厥人的戰爭可能被認為是一件賠本買賣,但他的指揮官們至少兩次俘獲大量俘虜以及牲畜。[85]

這使得帝國西部省區的經濟復甦得以興盛繁榮,這一復甦開始於曼努埃爾的祖父阿歷克塞一世時期,並一直持續到12世紀末。此外有觀點認為,12世紀的拜占庭帝國比希拉克略時薩珊波斯入侵帝國後五百多年裡任何時期都要更為富庶和繁榮。這一時期新修建的建築和教堂是非常好證據,即使在邊遠地區。這些證據強烈表明當時財富的分布之廣。[87]貿易也非常興盛;當時作為帝國最大商貿中心的君士坦丁堡,在曼努埃爾時代的人口據估計可達一百萬至五十萬之間,而且特別的活躍。他們不像共和時代和帝國時代的羅馬居民那樣安於消費不事生產。他們滿懷熱情(稅收制度束縛,卻未扼殺這種熱情),不僅致力於商業且致力於工業。君士坦丁堡既是一個政治首都,也是一個巨港和一流的工業中心,那裡存在各種各樣的生活方式和各種社會活動形式。在基督教世界,只有君士坦丁堡呈現出與現代大城市類似的景象,既有各種糾紛,各種缺陷,也有基本上屬於城市文明的各種講究。由於航運從未中斷,它與黑海沿岸、小亞細亞、南義大利以及亞得里亞海沿岸地區保持著聯繫。kommerkion是曼努埃爾主要的財富來源之一,它負責收取君士坦丁堡所有的進出口關稅。.[88]kommerkion每天能收取20000海培論的金錢。[89]

此外,君士坦丁堡自身也在不斷的擴展。這座城市國際大都會角色隨著義大利商人與前往聖地的朝聖者到來更加加強。威尼斯人、熱那亞人以及其他商人相繼與愛琴海地區的各大港口開啟商業貿易,並將十字軍諸國與法蒂瑪埃及的商品運往西方,而且還通過君士坦丁堡與拜占庭帝國貿易。[90]這些海商們刺激希臘、馬其頓以及希臘沿海各島嶼對商品的需求,並且從以農業為主的經濟模式中產生一種新財富來源。[91]帝國第二大城市塞瑟洛尼基舉辦的一場著名夏季集市吸引來自巴爾幹和更遠方商人們來到這裡繁華市場之中。在科林斯,絲織品刺激經濟的興盛。這一切都是科穆寧諸帝成功在這些核心地區保障一種「拜占庭和平」的明證。[87]

對於他宮廷中的修辭論者們來說,曼努埃爾是一位「神皇」。在他去世後的那一代人里,卓尼亞鐵斯將他稱為「諸帝中最受祝福者」,一個世紀後約翰· Stavrakios形容他為「偉乎嘉行」曼努埃爾軍隊中的一名士兵——約翰·福卡斯,在幾年之後將曼努埃爾描述為「救世主」和一位榮耀帝王。在法國、義大利以及十字軍諸國,曼努埃爾都被認為是當時世界上最強大的君主。[92]一位熱那亞分析家訃告中寫到「神聖記憶中的曼努埃爾大人,最蒙祝福的君士坦丁堡皇帝.....他的去世是整個基督教世界巨大損失。」[93]推爾的威廉稱曼努埃爾為」一位明智而謹慎的偉大君王,無論從哪一個方面都值得頌揚。」,「一位擁有偉大心靈的人並散發出無比能量」,「(對)他的記憶將會在賜福祈禱中被永遠留存。」就連第四次十字軍東征時,一位普通十字軍士兵克拉里的羅伯特也聽說曼努埃爾聲望甚高,認為他是一位值得敬重的人,並且認為他是所有基督徒中最富有且最慷慨的人。[94]

一個生動例子提醒人們曼努埃爾對十字軍諸國的影響是如此巨大,甚至我們在伯利恆的聖誕教堂也仍然能夠看到。十二世紀六十年代,教堂正廳被用以展示宗教會議為主體的馬賽克鑲嵌畫所裝飾。[95] 曼努埃爾就是這項工程的贊助人之一。在教堂南側牆壁,一串希臘語銘文寫到「獻給教堂的贈禮,由伊弗列姆的僧人、畫家以及馬賽克製作者完成,在偉大皇帝曼努埃爾·科穆寧以及偉大耶路撒冷國王阿馬爾里克的治下所完成。」曼努埃爾的名字被放在前面作為象徵,公眾普遍認同曼努埃爾的霸主地位,並且是整個基督教世界的領導者。曼努埃爾角色就像是東正教會以及聖地全體基督徒們的守護者,這也是他成功確保拜占庭在聖地權益的最好證據。曼努埃爾參加聖地許多希臘修道院和會堂中的建設與裝修,其中也包括耶路撒冷的聖墓教堂。多虧他的努力,拜占庭的神職人員才能每天在這裡舉行希臘禮祈禱儀式。所有這些努力都強化他在十字軍諸國中的霸主地位,與安條克親王雷納德和耶路撒冷國王阿馬爾里克的協議也確保他對安條克和耶路撒冷的支配權。曼努埃爾同時也是最後一位在巴爾幹取得軍事和外交勝利的拜占庭皇帝,我們也可以稱他為「達爾馬提亞、波士尼亞、塞爾維亞、保加利亞以及匈牙利的統治者」。[96]

1180年曼努埃爾去世時的拜占庭帝國表面上依然強大,他在去世前不久,還舉辦他兒子阿歷克塞二世與法國國王路易七世的女兒阿格尼斯的訂婚慶典。[97]歸功於阿歷克塞一世、約翰二世和曼努埃爾一世在外交和軍事上的努力,此時的帝國國力才會如此強大,經濟上是如此的繁榮,邊疆是如此的穩定;但盛世背後也存在嚴重的問題。在內部,拜占庭皇室中需要一位強有力的領袖去使他們團結起來,越來越多挑戰來自於日益膨脹的皇室內部,但曼努埃爾的去世大大危害帝國內部穩定性。帝國的一些外敵潛伏在側翼,等待進攻的時機,尤其是安納托利亞的突厥人——曼努埃爾最終也沒能徹底擊敗的敵人,還有諾曼西西里人——他們已經多次入侵帝國,但最終以失敗告終。甚至還有威尼斯人,拜占庭最重要的西方盟友,在1180年曼努埃爾去世時,與帝國關係惡劣。鑑於這種情況,帝國需要一位強大帝王來確保能夠對抗面臨的外敵威脅,之後重建帝國枯竭的國庫。但曼努埃爾的兒子還未成年,並且他不受歡迎的攝政政府最終被一場政變所推翻。拜占庭國家實力正是依賴於王朝的團結與穩固,而這一動盪的繼承削弱這一點,好戰鄰國們和野心勃勃臣屬們看到他們的機會。[97]

註腳

^ a: The mood that prevailed before the end of 1147 is best conveyed by a verse enconium to Manuel (one of the poems included in a list transmitted under the name of Theodore Prodromos in Codex Marcianus graecus XI.22 known as Manganeios Prodromos), which was probably an imperial commission, and must have been written shortly after the Germans had crossed the Bosporus. Here Conrad is accused of wanting to take Constantinople by force, and to install a Latin patriarch (Manganeios Prodromos, no 20.1).[98]

^ b: According to Paul Magdalino, one of Manuel's primary goals was a partition of Italy with the German empire, in which Byzantium would get the Adriatic coast. His unilateral pursuit, however, antagonized the new German emperor, Frederick Barbarossa, whose own plans for imperial restoration ruled out any partnership with Byzantium. Manuel was thus obliged to treat Frederick as his main enemy, and to form a web of relationships with other western powers, including the papacy, his old enemy, the Norman kingdom, Hungary, several magnates and cities throughout Italy, and, above all, the crusader states.[97]

^ c: Magdalino underscores that, whereas John had removed the Rupenid princes from power in Cilicia twenty years earlier, Manuel allowed Toros to hold most of his strongholds he had taken, and effectively restored only the coastal area to imperial rule. From Raynald, Manuel secured recognition of imperial suzerainty over Antioch, with the promise to hand over the citadel, to instal a patriarch sent from Constantinople (not actually implemented until 1165–66), and to provide troops for the emperor's service, but nothing seems to have been said about the reversion of Antioch to direct imperial rule. According to Magdalino, this suggests that Manuel had dropped this demand on which both his grandfather and father insisted.[20] For his part, Medieval historian Zachary Nugent Brooke believes that the victory of Christianity against Nur ad-Din was made impossible, since both Greeks and Latins were concerned primarily with their own interests. He characterises the policy of Manuel as "short-sighted", because "he lost a splendid opportunity of recovering the former possessions of the Empire, and by his departure threw away most of the actual fruits of his expedition".[99] According to Piers Paul Read, Manuel's deal with Nur ad-Din was for the Latins another expression of Greeks' perfidy.[17]

^ d: Alexios had been ordered to bring soldiers, but he merely brought his empty ships to Brindisi.[31]

^ e: In 1155 Hadrian sent legates to Manuel, with a letter for Basil, Archbishop of Thessaloniki, in which he exhorted that bishop to procure the reünion of the churches. Basil answered that there was no division between the Greeks and Latins, since they held the same faith and offered the same sacrifice. "As for the causes of scandal, weak in themselves, that have separated us from each other", he added, "your Holiness can cause them to cease, by your own extended authority and the help of the Emperor of the West."[100]

資料來源

延伸閱讀

外部連結

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.