气候变化政治

来自维基百科,自由的百科全书

气候变化政治(英语:Politics of climate change)指的是不同群体为应对气候变化所具的不同观点(如因应策略的歧异、利益冲突、科学认知的差距及政治考量)。气候变化主要是由人类经济活动所排放的温室气体造成,特别是由燃烧化石燃料、制造水泥和生产钢铁等,加上农业和林业的土地利用及土地利用改变所产生。自第一次工业革命以来,化石燃料为经济和开发活动提供重要的能源。科学界普遍认为气候政策有其必要(参见关于气候变化的科学共识),但居中心地位的化石燃料和碳密集型产业却对此种气候友善政策予以强烈抵制。

气候变化在20世纪70年代首次成为一种政治议题。自1990年代以来,缓解气候变化倡议一直在国际政治议程上居重要地位,也在国家和地方层面日益受到重视。气候变化是一个复杂的议题。全球任何一处的温室气体排放都会导致气候变化。然而影响的差异各异,取决于地点或经济体对影响存有的脆弱性。总体上气候变化造成的是负面影响,预计因气温持续升高,此种影响会进一步恶化。而从化石燃料和再生能源两者中受益的能力会因国家而异。

世界各国所担负的责任、享受的利益及与所受气候相关的威胁促使早期举行的气候变化会议,除发布解决问题的一般性意向声明以及发达国家提出不具拘束力减少排放的承诺之外,几乎没什么成果。而进入21世纪后,为帮助脆弱国家进行调适气候变化,而越来越关注气候融资等机制。在一些国家和地方司法管辖区,已采取的气候友善政策远高于国际层面的承诺程度,然而除非全球温室气体排放总量能够下降,否则所能达成的局部性温室气体排放减少,在缓解全球暖化的成效上将会有限。

进入2020年代之后,以再生能源取代化石燃料的可行性显著提升,有些国家现在几乎所有电力都由再生能源生产。公众对气候变化威胁的认识有所提升 - 在很大程度上是由于青年气候运动以及人们对气候变化影响(例如极端天气事件和海平面上升引发的洪水)的理解。许多调查显示有越来越多的选民支持应对气候变化,使得政治人物更易致力于倡导包括气候行动在内的政策。 COVID-19大流行和其导致的经济衰退引发人们广泛呼吁进行"绿色复苏",欧盟等一些国家成功地将气候行动纳入政策变革。到2019年,彻底采气候变化否定论观点者的影响力已大幅减弱,这类反对派改而转向鼓励采取拖延或是不行动的策略。

政策辩论

有关气候变化的政治辩论从根本上讲均与采取行动有关。[1]不同的论点支围绕着气候变化政治 - 例如对威胁急迫性的评估,以及对各种应对措施的可行性、优缺点评估。但本质上都与气候变化的潜在反应有关。[1]

构成政治论点的陈述分为两种:实证陈述和规范性陈述。实证陈述通常可透过仔细的名词定义和科学证据来澄清或是反驳。而关于一个人"应该"做什么的规范性陈述通常至少部分与道德有关联,且本质上是个判断问题。经验显示如果参与者试图理清其论点的实证部分和规范部分,如一开始就实证部分达成一致看法,在辩论时往往可取得更好的进展。在辩论早期阶段,参与者的规范立场可能会受到他们所代表选区最大利益观点的强烈影响。 哥斯达黎加外交官克里斯蒂娜·菲格雷斯等人指出,在2015年的巴黎协定之能签订成功,是因为重要参与者能超越有关利益冲突的竞争性思维,转向反映基于共享协作思维的规范性陈述才能达成。[2][note 1]

应对气候变化的行动可分为三类:缓解 - 减少温室气体排放和强化碳汇的作为、调适 - 抵御全球暖化负面影响的行动以及太阳辐射调节(SRM,一种将阳光反射回外太空的技术,但此概念于后来并未有进一步的研究)。[3]

发生于20世纪关于气候变化的国际辩论几乎全集中在缓解问题上,过于注重调适有时被认为是失败主义者。此外调适多数是种地方性问题。到21世纪初,虽然缓解仍是政治辩论中最受关注的问题,但已不再是唯一的焦点。如今某种程度的调适行动被广泛认为有其必要,且至少在高层上已进行过国际讨论,但在采取哪些具体行动仍会交由地方处理。 2009年联合国气候变化大会的结论中有每年向发展中国家提供1,000亿美元资金的承诺。随后于2015年在巴黎举行的会议提出澄清,资金分配会在调适和缓解间做平衡分配,但截至2020年12月,承诺的资金并未完全拨出,且已交付的主要是用在缓解项目。[4][5]到2019年,所谓气候工程的可能性的讨论也越来越多,预计在未来的辩论中会变得更为凸显。[3][6]

关于如何缓解气候变化的影响,此类政治辩论往往会根据相关政体的规模而有不同。国际辩论较国家级和市级辩论须考虑较多的因素。于1990年代,当气候变化首次成为政治议程中的重要议题时,人们乐观认为此问题可成功解决。于1987年签署为保护地球臭氧层的《蒙特利尔议定书》显示世界能采取集体行动来应对科学家所提的威胁,甚至是当其尚未对人类造成重大伤害之前即会采取行动。然而到2000年代初,温室气体排放量持续上升,几乎没惩罚排放者或奖励气候友善行为的协议出现。很明显的,要达成有效行动以限制全球暖化的协议具有挑战性。[note 2][3][7]

气候变化于1990年代初成为全球政治议程的固定议题,联合国气候变化会议每年举行一次。这些年度活动也称为缔约方会议 (COP)。其中有里程碑意义的会议是于1997年签订《京都议定书》的、2009年联合国气候变化大会(又称哥本哈根气候变化会议)和2015年于巴黎举行的2015年联合国气候变化大会。京都议定书最初被认为是项很有前途的协议,但到2000年代初,结果却令人失望。哥本哈根会议做出超越京都议定书的重大尝试,提出更强而有力的一批承诺,但基本上也以失败收场。2015年会议被广泛认为是成功的,但它在长期降低全球暖化方面的效果仍有待观察。[3]

各国在国际层面上可尝试透过三种减排方法进行谈判。首先是设定减排目标,其次是制定碳定价,最后是创建一套基本上属于自愿性的流程来鼓励减排,其中包括资讯共享和进度审查的机制。这些方法在很大程度上有互补性,但在各种会议时,往往多数会聚焦在单一的方法上。到2010年左右,国际谈判主要集中在设定排放目标。 由《蒙特利尔议定书》在减少排放破坏臭氧层的工作取得成功,显示设定目标可能是有效的。然而就温室气体减量而言,设定目标在总体上未能带来大幅减排的结果。深具雄心的目标通常无法实现。施加严厉惩罚以激励人们更努力实现具有挑战性的目标的尝试,总会受到至少一两个国家所阻止。[8]

进入21世纪,人们普遍认为碳定价是减少排放的最有效方法,至少在理论上是如此。[9]但各国一直不愿采用高的碳价格,或是在大多数情况下根本不愿采用碳定价。不愿意的主要原因之一是碳泄漏问题,即将产生温室气体排放的活动从征收碳定价的管辖范围中外移,导致管辖范围内的就业和收入受到剥夺,因为排放会在其他地方发生,难以产生任何实质上的好处。虽说如此,碳定价所覆盖的全球排放量占比已从2005年的5%上升到2019年的15%,一旦中国碳定价全面生效,这一比例应会达到40%以上。现有的碳定价制度大部分是由欧盟、一些国家和次国家司法管辖区自行实施。[10]

各国制定自己的减排计划,很大程度上是1991年引入的自愿性承诺和审查制度,但在京都议定书签署之前(1997年)已被放弃,京都议定书的重点是达成一致的"由上而下"的排放目标。这种自愿性做法在哥本哈根会议重新出现,并在2015年《巴黎协定》中得到进一步重视,但承诺被改称为国家自订贡献,承诺应每隔5年重新提交一次。这种方法的效果还有待观察。[11]一些国家在2021年于苏格兰格拉斯哥召开的第26届联合国气候变化大会前后提交数量更高的国家自订贡献。签署国于同一会议中也通过碳交易的会计规则。[12]

| 高 | 中 | 低 | 甚低 |

减少温室气体排放的政策由国家或次国家司法管辖区制定,而在欧盟是在区域层级制定。许多已实施的减排政策已高于国际协议的标准。例如美国一些州引入碳定价,或是哥斯达黎加在2010年代已实现99%的电力由再生能源产生。

大多数减少排放或部署清洁能源技术并非由政府本身出面,而是由个人、企业和某些组织付诸实现。然而制定气候友善活动政策的是国家和地方政府。这类政策大致分为四种:一是实施碳定价机制和各种财政激励措施、其次是订立规范性法规,例如规定一定比例的发电量必须来自再生能源、第三是政府直接支付用于气候友善活动或研究的经费,以及第四,采用资讯共享、教育和鼓励自愿性气候友善行为的方法。[3]地方政治活动有时与空气污染有关联,例如在城市中建立低排放区的行动也可能是为减少道路运输的碳排放。[13]

个人、企业和非政府组织可直接或间接影响气候变化政治。采用的机制包含有个人言论、透过民意调查表达集体意见以及发动大规模抗议活动。史上这些抗议活动中有很大部分是反对气候友善政策的。类似于英国燃油抗议活动,世界各地自2000年起已发生数十起反对燃油税或终止燃油补贴的抗议活动。自2019年气候大罢课和反抗灭绝运动出现以来,支持气候变化抗议的活动变得更加突出。非政治行为者影响气候变化政治的间接方式包括有资助或研究绿色技术,以及从化石燃料产业撤资运动。[3]

有许多特殊利益团体、组织和公司在全球暖化这个议题上拥有公共和私人立场。以下是对全球暖化政治怀有兴趣的特殊利益团体的大致分类:

- 化石燃料公司:传统化石燃料公司可能会因更严格的法规而蒙受损失(或其中也可能有例外)。化石燃料公司从事能源交易可能代表它们参与碳交易计划和其他此类机制会带来独特的优势,因此尚不清楚是否每个传统化石燃料公司都一定会反对更严格的政策。[14]例如已于2000年倒闭的安隆公司曾大力游说美国政府监管二氧化碳,该公司认为如果能取得能源交易的中心地位,就有机会主导能源产业。[15][16][17]

- 农民和农业综合企业是重要的游说团体,但他们在气候变化对农业的影响、[18]农业温室气体排放[19]以及欧盟的共同农业政策的作用等问题上的看法并不相同。[20]

- 金融机构:金融机构普遍支持因应气候变化的政策,特别是实施碳交易计划和建立将碳定价与碳挂钩的市场机制。这些新市场需要交易基础设施,而银行机构可以提供。金融机构也有能力投资、交易和开发各种金融工具,透过碳交易以及利用经纪、保险和衍生工具等金融功能来获取利益。[21]

- 环保团体:环保倡议团体普遍赞成严格限制二氧化碳排放。环保团体致力于提高人们对排放影响的认识。[22]

- 再生能源和能源效率公司:风能、太阳能和能源效率公司普遍支持更严格的政策。他们预计因化石燃料透过交易计划或税收变得更加昂贵时,他们在能源市场的占比将有机会扩大。[23]

- 核能发电公司:支持并受益于碳定价,或是享有低碳能源补贴。核电产生的温室气体排放量最少。[24]

- 配电公司:可能会因太阳能发电场的设立而失去部分市场,但会为电动车提供充电网络而受益。[25]

- 传统零售商和行销商:传统零售商、行销人员和一般企业透过采取与客户产生共鸣的政策来应对。如果"绿色环保"能吸引客户,那么他们就可采取适度的计划,与客户站在同一阵线来达到取悦客户的目的。但因其总公司并未从其特定立场中获利,因此它们将不太可能强烈游说支持或反对更严格的政策。[26]

- 医事人员:他们常提起当气候变化和空气污染如能一起解决时,就可挽救数百万人的生命。[27]

- 资讯和通讯技术公司:提出它们的产品可帮助人们应对气候变化,往往可因较少的差旅,且有许多人购买绿色电力而受益。[28]

不同的利害相关者有时会联合起来强化其讯息,例如电力公司资助购买电动校车,透过减少空气污染而降低来自医疗服务的负担,同时又能销售更多的电力。有时业界会资助专业性非营利组织,根据其要求以提高意识,并进行游说。[29][30]

集体行动

当前的气候政治受到许多社会和政治运动的影响,这些运动专注于建立气候行动政治意愿中的不同部分。包括气候正义运动、青年气候运动和从化石燃料产业撤资运动。

本节摘录自从化石燃料产业撤资。

从化石燃料产业撤资(或称从化石燃料产业撤资及投资气候解决方案)是一种对机构投资者施加社会、政治和经济的压力,要求其从与化石燃料开采相关的产业撤资(包括股票、债券及其他财务工具)以减少气候变化的行动,。

美国的大学校园于2011年兴起此项撤资运动,学生们敦促政府将给予化石燃料产业的财务投资转变为对清洁能源和受气候变化影响最严重社区的投资。[32]缅因州优尼蒂环境科技大学于2012年成为第一所从化石燃料产业撤除[33]财务投资的高等教育机构。

据报导迄2015年,由化石燃料产业撤资是史上成长最快的撤资运动。[34]截至2023年7月,全球有超过1,593家机构,资产总额超过40.5兆美元,已开始或承诺某种形式的从化石燃料产业撤资。[35]

1000

1000+

10000+

100000+

1000000+

为气候而罢课(瑞典语:Skolstrejk för klimatet)亦称周五为未来而战(英语:Fridays for Future (FFF))、青年需要良好气候(Youth for Climate)、气候罢课(Climate Strike/Climatestrike)或青年为气候罢课(Youth Strike for Climate),是项由学生在周五罢课,参加示威活动的国际运动,诉求是政治领导人该采取行动以缓解气候变化,以及化石燃料行业该转而生产再生能源。

瑞典学生格蕾塔·童贝里于2018年8月在瑞典议会外举著书写“Skolstrejk för klimatet”(“为气候而罢课”)的牌子进行举抗议活动,随后世界各地展开宣传和广泛的组织活动。[36][37]

在2019年3月15日举行的全球罢课,聚集超过100万人,在125个国家共进行2,200次活动。[38][39][40][41]第二次全球罢课于2019年5月24日举行,在150个国家共进行1,600起活动,有数十万人参与。 于5月的抗议活动特地选在2019年欧洲议会选举期间举行。[40][42][43][44]

在2019年9月进行的气候罢课(Global Week for Future),总计在150多个国家/地区共举行过4,500起罢课,集中在9月20日(2019年联合国气候行动峰会前三日)星期五和9月27日星期五,也包含有在两日之间的活动。 于9月20日的罢课是世界史上最大规模的为气候而罢课,聚集大约400万名抗议者,其中许多是学童,德国的参与者有140万名。[45]

在9月27日的一场,估计在世界各地共有200万人参加,其中包括超过100万意大利抗议者和数十万加拿大的抗议者。[46][47][48]目前展望

史上透过政治手段就限制全球暖化政策而达成一致的协议,在很大程度上并未达成缓解气候变化的目的。[49][50]评论者乐观认为由于最近的各种发展和早期未出现的机遇,在2020年代可能会较为成功。而其他评论者则警告说现在企图将全球升温幅度控制在1.5°C以下,甚至很有可能必须将升温幅度控制在2°C以下,所余的时间已无几。[3][51][52][53]

在2010年代后期,因有利于气候友善政治的各种发展让评论家表示乐观,认为2020年代在应对全球暖化威胁方面可能会取得良好进展。[3][51][52]

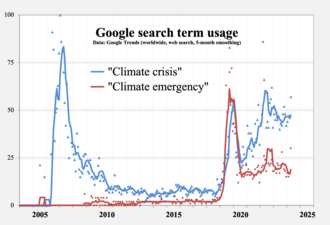

根据Google搜索趋势的数据,线上对于"气候危机"(climate crisis) 和"气候紧急事件"(climate emergency) 等名词的搜寻量于2019年激增。 类似的激增事件也发生在2006年,于美国前副总统艾尔·高尔制作的纪录片不愿面对的真相上映之后出现。

2019年被描述为"世界对气候变化觉醒的一年",推动因素包括人们因近期极端天气事件、格蕾塔·童贝里效应和IPCC全球升温1.5ºC特别报告的发表而日益了解到全球变暖的威胁。[55][56]

石油输出国组织(OPEC)秘书长于2019年承认学校罢课运动是化石燃料产业面临的最大威胁。[57]根据克里斯蒂娜·菲格雷斯的说法,一旦有大约3.5%的人口开始参与非暴力抗议,就有机会能成功引发政治变革,格蕾塔·童贝里成功发起的的"气候大罢课"运动显示此一门槛不难达成。[58]

由细胞出版社发行的期刊《同一地球(One Earth)》上刊出的一项2023年回顾研究,提出民意调查显示大多数人认为气候变化正在发生,并且与我们息息相关。[59]这篇报告的结论是将气候变化当作是遥远的事并不一定会导致气候行动减少,而缩短心理上的距离也并不能保证人们会加强气候行动。[59]

到2019年,彻底否认气候变化的影响力已比前几年小得多。原因包括有极端天气事件频率增加、气候科学家之间更有效的沟通以及格蕾塔·童贝里效应。[60][61][62][63][64]

再生能源是种取之不尽、用之不竭的自然能源。主要的再生能源有风能、水力、太阳能、地热能和生物质能。 再生能源发电于2020年占世界生产电力的29%。[65]

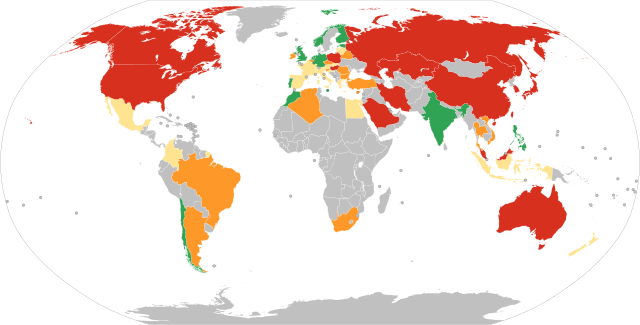

《巴黎协定》于2015年签订后,截至2021年11月,于196个缔约方中已有194个提交国家自订贡献(NDC,即气候承诺)。[66][67]这些国家采取许多措施将再生能源投资纳入,例如有102个实施税收抵免,101个纳入某种公共投资,100个目前采用减税措施。最大的二氧化碳排放国是美国、中国和印度。这些国家尚无足够的产业政策以将承诺的政策全部付诸实施。[68]

2021年联合国气候变化大会(COP26)于当年11月在苏格兰格拉斯哥举行。近200个国家同意加速应对行动,并提出更有效的气候承诺。一些新的承诺包含有对甲烷排放、森林砍伐和煤炭融资进行变革。连美国和中国(两个最大的碳排放国)均同意共同努力,防止全球升温超过摄氏1.5°C。[69]但有科学家、政治家和活动家表示本次高峰会做得还不够,全球仍会达到升温1.5°C的临界点。于2009年成立的研究机构气候行动追踪发布的一份独立报告称这些只是"口头承诺","到2030年,我们的排放量大约会是需要控制升温在1.5°C内的两倍。"[70]

截至2020年,使用核能,特别是再生能源以取代化石燃料能源的可行性已大幅增加,目前已有数十个国家,其一半以上的电力来自再生能源。[71][72]

本节摘自绿色复苏方案。

绿色复苏方案是一系列拟议的环境、监管和财政改革,目的在经济危机(例如COVID-19大流行或2007年—2008年环球金融危机(GFC))之后重建繁荣。方案涉及在恢复经济成长的同时也积极创造有利环境的措施,包括再生能源、高效能源利用、基于自然的解决方案、永续交通系统、绿色创新和绿色就业等措施。[73][74][75][76]

全球多个政党、政府、活动人士和学术界对COVID-19大流行之后的绿色复苏方案表示支持。[77][78]该方案除采用与应对GFC的类似措施之时,[79]还含有一关键目标 - 确保应对经济衰退的行动也能应对气候变化。行动计划中包括减少煤炭、石油和天然气使用、清洁交通、再生能源、生态友善建筑以及永续的企业或金融措施。绿色复苏方案倡议得到联合国和经济合作暨发展组织 (OECD) 的支持。[80]多项全球倡议提供在国家财政应对措施的即时跟踪机制,包括全球复苏观察站(Global Recovery Observatory,英国牛津大学、联合国和国际货币基金组织(IMF)联合组成)、[81]能源政策追踪组织(Energy Policy Tracker)、[82]和OECD的绿色复苏追踪组织(Green Recovery Tracker)。[83]

全球复苏观察站于2021年3月发布的分析报告提出在区分救援和复苏投资时,预计有18%的复苏投资和2.5%的总支出预计将可增强永续性。[84]国际能源署于2021年7月对此分析予以支持,指出全球只有约2%的经济救助资金流向永续能源。[85]根据2022年对二十大工业国用于刺激经济的14兆美元的分析,只有约6%的复苏支出分配给同时也能减少温室气体排放的领域,包括车辆电气化、提高建筑物能源效率和配置再生能源设施。[86]

虽然有看似乐观的各项条件,评论家提出警告,提醒仍有一些困难挑战在前,如果气候变化政治要促成温室气体排放量大幅减少,就需将这些挑战克服。[3][51][52]例如为肉类消费增加税收在政治上可能是件很困难的事。[87]

截至2021年,全球大气中的二氧化碳浓度已较第一次工业革命前的平均数字增加约50%,每年排放量增加数十亿吨。全球暖化已跨越对一些地区产生灾难性影响的阀值。因此如果要避免环境影响升高的风险,就需尽快实施重大政策变革。[3][51][52]

目前化石燃料仍是世界经济的核心,截至2019年约占全球发电能源的80%。突然取消对消费者的化石燃料补贴往往会引发骚乱。[88]虽然清洁能源有时会较为便宜,[89][note 3]但企图在短时间内大量提供再生能源具有挑战性。[3][6][7]根据国际能源署于2023年发布的报告,燃烧煤炭的温室气体排放量增加2.43亿吨,达到近15.5吉吨(Gt,十亿吨)的历史新高。这1.6%的成长率高于过去十年0.4%的年平均成长率。[90]欧洲中央银行于2022年认为传统能源的高价格正加速能源转型,可让人们远离化石燃料,但各国政府应采取措施防止能源贫困发生,同时又不阻碍向低碳能源转型。[91]

于2020年代,彻底否认气候变化的情况比之前的几十年要少得多,但仍有许多人反对采取限制温室气体排放的行动。这些论点的观点有:有更好运用资金的方式(例如气候变化适应)、最好等到新技术开发出来,而让缓解成本更为便宜,及当技术和创新后,会让气候变化变得毫无意义或是获得解决。[92][93]

由石油巨头及行业游说组织美国石油学会 (API) 已花费大量经费进行游说和政治运动,并雇用大批游说者,以阻碍和拖延政府应对气候变化的行动。化石燃料游说团体在华盛顿哥伦比亚特区和其他政治中心(包括欧盟和英国)具有相当大的影响力。[94][95][96][97][98][99]化石燃料产业利益集团在权力中心推动其议程的花费是普通公民和环保活动人士的许多倍,前者在2000年至2016年期间花费20亿美元于美国的气候变化相关游说。[100][101]最大的五家石油公司花费数亿欧元在布鲁塞尔为其议程游说。[102]大型石油公司口口声声说"可持续发展原则",但其雇用的游说者所传达的却会导致人们对气候变化的现实和影响产生怀疑,而阻碍政府解决这些问题的进程。API曾发起一场虚假资讯的公共关系运动,目的是在公众心中制造疑虑,让"气候变化不再成为一种问题。"[94][94][101]此产业还在美国政治竞选活动上投入大量资金,在过去几十年中,其政治捐献中大约有2/3为共和党籍参政者提供动力,[103]这类支出比倡导再生能源团体的政治捐款高出许多倍。[104]化石燃料产业的政治捐款给予投票反对环保的政治人物以支持。根据《美国国家科学院院刊》发表的一项研究报告,如果国会议员的投票变得更加反环境(根据支持环保投票者联盟)(LCV)的分数纪录来衡量),议员收到的化石燃料行业捐款就会有所增加。平均而言,LCV分数下降10%与化石燃料产业在国会任期后收到的竞选活动捐款增加1,700美元有关联。[105][106]

石油巨头早在1970年代就已压制公司内部科学家关于燃烧化石燃料会对气候造成重大影响的报告。埃克森美孚发起一场企业宣传活动,传播有关气候变化的虚假信息,这一策略可与大型烟草公司欺蒙公众有关吸烟危害的公关活动相比拟。[107]化石燃料产业资助的智库会骚扰公开讨论气候变化威胁的气候科学家。[108]早在1980年代,当更多的美国大众开始意识到气候变化问题时,一些总统任内的决策部门就对公开对化石燃料会构成气候威胁科学家的观点嗤之以鼻。[109]其他总统任内的决策部门则要气候科学家闭嘴,并压制揭露问题的举报者。[110]许多联邦机构的政治任命人员阻止科学家报告有关气候危机的发现,或是改变数据模型以得到他们先前提出的结论,并拒绝接受机构内科学家的意见。[111][112][113]

在哥伦比亚、巴西和菲律宾等多个国家,有越来越多气候和环境活动人士,包括保护林地免受伐木业侵害的活动人士遭到杀害。大多数肇事者并未受到逮捕与惩罚。 此类杀戮数量在2019年创下历史新高。其中原住民环保活动人士占全部死亡人数的40%。[114][115][116]一些政府(例如美国)的国内情报部门将环保活动人士和气候变化组织视为"国内恐怖分子",对他们进行监视、调查、审问,并将他们列入国家"观察名单人士",而可能使他们更难登机,并可能引发当地执法机构监控。[117][118][119]美国的其他策略包括阻止媒体报导美国公民集合和进行气候变化抗议活动,并与私人保全公司合作以监视活动人士。[120]

在气候变化政治的背景下,末日论指的是悲观的叙述,声称现在对气候变化采取任何行动都为时已晚。末日论可能包括夸大气候临界点的可能性,以及即使人类能够立即停止使用化石燃料,仍会引发超出人类控制能力的失控可能。在美国的民意调查发现对于那些不支持采取进一步行动以限制全球暖化的人来说,认为现在采取行动为时已晚是比对人为气候变化持怀疑态度更常见的原因。[121][122]

一些气候友善政策在立法过程中受到环境和/或左派压力团体和政党的阻挠。例如于2009年,澳大利亚绿党投票反对碳污染减排计划,因为他们认为该计划没有施加足够高的碳价。在美国,草根环境组织塞拉俱乐部助阵,阻止2016年气候税法案通过,因为他们认为该法案缺乏社会正义。在美国各州实施的一些碳定价尝试已被左派政客阻止,因为这些是透过碳定价(又称限额与交易机制 cap and trade)而非税收来执行的。[123]

气候变化议题通常涉及不同的部门,表示经常需要将气候变化政策纳入其他政策领域。[84]因为此需要在复杂的治理过程中涉及不同的参与者,透过多个层面解决,最终导致问题变得更为困难。[124]

要成功调适气候变化需要将相互竞争的经济、社会和政治利益之间作平衡处理。当发生平衡不足时,有害的后果可能会抵消调适措施的好处。例如坦桑尼亚保护珊瑚礁的工作迫使当地村民从传统的捕鱼活动转向产生更多温室气体排放的农业活动。[125]

科技的前景既被视为威胁,也被视为可能的福音。新技术可为新的、更有效的气候政策开辟可能性。大多数电脑模型显示将升温限制在2°C的路径中,二氧化碳移除(缓解气候变化的方法之一)具有重要作用。来自各个政治派别的评论家都倾向欢迎此种技术。但有些人怀疑此技术是否能在不迅速减少排放的情况下消除足够的二氧化碳而达到缓解的目的,他们警告说,对此类技术过于乐观可能会让实施缓解政策变得更加困难。[3][51]

太阳辐射调节是另一项减少全球暖化的技术,透过于平流层中注入气溶胶,人们普遍认为这将有效降低全球平均气温。然而许多气候科学家认为这种技术的前景不受欢迎,并警告说,副作用包括由于阳光和降水量减少可能会导致农业产量下降,以及可能出现局部气温上升和其他天气干扰。根据美国气候学家迈克尔·曼的说法,利用太阳辐射调节来降低地球升温,是种降低制定减排政策意愿的另一手法。[126][51][127]

公正过渡

逐步淘汰煤炭开采、养牛业[[128]或底拖网捕捞[129]等碳密集型活动所造成的经济破坏可能具有政治敏感性,因为一些国家的煤矿工人、[130]农民[131]和渔民[132]的政治地位往往较高,其生计受到影响就容易引发抗争,导致政策难以推动。许多劳工和环境团体主张公正过渡,以最大限度减少与气候相关的变化所带来的危害,并最大限度提高其效益,例如为受影响者提供职业训练。

政治领域中不同的反应

气候友善政策普遍得到各个政治派别的支持,但偏向右派的选民和政客中有许多例外,甚至左派政客也很少将应对气候变化作为首要任务。[139]在20世纪,右派政治人物在国际和国内领导过许多重大应对气候变化的行动,美国前总统理查·尼克森和英国前首相撒切尔夫人两人就是突出的例子。[140][141]然而到20世纪90年代,特别是在一些英语国家(尤其是在美国),这个问题开始两极化。[7][3]右派媒体开始辩称气候变化是左派人士所捏造,或至少是夸大的,以支持扩充政府规模的合理性。[note 4]截至2020年,一些右派政府已颁布更多的气候友善政策。各种调查显示就连美国右派选民也出现对全球暖化不再那么怀疑的轻微倾向,美国环境保护联盟等组织表明年轻的共和党选民将气候作为一个核心政策领域。但在英国作者阿纳托尔·利文看来,在一些美国右派选民来说,对气候变化持怀疑态度已经成为他们身份的一部分,因此他们在这个问题上的立场不能通过理性论证轻易改变。[142][143][63] [144]

德国多特蒙德工业大学于2014年发表的一项研究报告,结论是1992年至2008年期间,中间和左派政府的国家比OECD国家的右派政府的减排量更高。[145]从历史上看,持民族主义信念的政府一直是在制定环保政策表现最差的政府之一。但利文认为随着气候变化越来越被视为对民族国家存在的威胁,民族主义可能成为推动缓解工作最有效的力量之一。将气候变化威胁予以安全化的日益增长趋势,对于取得更多民族主义者和保守派的支持可能会特别有效。[142][134][3]

历史

本节摘自气候变化政策与政治史。

气候变化政策和政治史涵盖与此议题相关的政治行动、政策、趋势、争议和积极分子奋斗的历程。气候变化在1970年代浮上台面成为政治议题,当时的活动人士和政府部门开始努力促使全球正视环境危机。[146]有关气候变化的国际政策着重于合作,以及制定国际方针来应对气候变化问题。 《联合国气候变化纲要公约》(UNFCCC)是受广泛接受的国际协议,其内容也不断更新以应对新挑战 。各国因应气候变化的国内政策,则着重于制定减少温室气体排放的内部措施,以及将国际方针纳入本国法律之中。

进入21世纪,气候政策出现重大转变,开始更加关注因环境异常而首当其冲的弱势群体。[147]纵观气候政策的历史,对于发展中国家所受到的待遇一直存在争议。采批判性反思气候变化政治史,可为我们提供"思考人类史上最棘手问题之一的方法,而此问题正是我们人类在星球上短暂存留期间自找的"。[148]

与气候科学的关系

科学文献中已存在压倒性的共识,即全球近几十年来的地表气温有所上升,且主要是由人为排放的温室气体所造成。[149][150][151]

科学政治化是指为取得政治利益而操弄科学,是一种政治过程。在智慧设计[156][157](类似于楔形策略)争议,或是利益驱动型的科学否定者争议中均出现过,这些科学家涉嫌故意模糊研究结果,例如关于使用烟草、臭氧层耗损、气候变化或酸雨等问题。[158][159]例如在臭氧层耗损的案例中,在高度不确定性和遭受强大阻力的情况下终于完成《蒙特利尔议定书》签署,达成全球监管的目标,[160]然而在气候变化,虽然签署有《京都议定书》,却是一个失败案例。[161]

联合国政府间气候变化专门委员会(IPCC )试图汇集及整理全球气候变化研究的结果,以形成全球共识,[162]但IPCC本身即为一强烈政治化的组织。[163]导致人为造成的气候变化从单纯的科学议题演变为全球性的首要政策议题。[163]

IPCC已建立广泛的科学共识,但这并不能阻止各国政府追求不同的(即使并非相反的)目标。[163][164]而在臭氧层耗损方面,却在达成科学共识之前,即已完成全球监管布置。[160]因此拥有越多的知识可能会有越好政治反应的这种线性思维并不一定正确。要有效制定气候变化政策,仅靠既有的科学知识并不足够。[163]更关键的是我们需要理解科学、公众认知 (或认知的缺乏) 与政策之间的关系,才能成功管理知识和不确定性,作为政治决策的基础。[161][164][165][166]

大多数有关缓解气候变化的政策辩论都聚焦于二十一世纪的预测。学者批评这是种短期思维,因为未来几十年所做的决定将会影响往后几个千禧年的环境。[167]

估计用于气候相关研究的所有经费中只有0.12%用于缓解变化相关的社会科学研究。[168]更多的经费被用于相关的自然科学研究,而大量经费挹注于研究气候变化的影响和调适。[168]有人认为这是一种资源的错配 - 有关气候变化的自然科学方面已很成熟,也还有几十年甚至几个世纪的时间来处理调适问题,最迫切的是如何改变人类行为,立即行动,来缓解气候变化。[168]

气候变化政治经济学

气候变化政治经济学是应用有关社会和政治过程的政治经济学思维,来研究气候变化决策中关键问题的方法。

人们对气候变化的认识和急迫性不断增强,促使学者探索更好理解影响气候变化谈判的众多主体和影响因素,并寻求更有效的应对方案。从政治经济学角度分析这些复杂问题,有助于解释不同利害相关者之间在应对气候变化影响时的互动,而为能更好实施气候变化政策提供机会。

气候变化已成为当今社会最迫切的环境议题和全球挑战。随着此议题日益成为国际议程中的重要议题,不同学术界的研究人员一直致力于探索应对此种变化的有效解决方案。技术专家和规划者持续在寻找缓解和调适的方法、经济学家估算变化产生的成本以及应对需花费的成本及发展专家探讨变化对社会服务和公共福祉的影响。然而研究人员Cammack(2007年)[169]指出上述讨论中的两个问题,即不同学科提出的气候变化解决方案之间的脱节及地方层级应对行动中缺乏政治参与。此外气候变化问题还面临其他的挑战,例如菁英将资源垄断问题、发展中国家的资源不足以及由于此类限制经常引发的冲突,而这些问题在解决方案提议中往往较少受到关注和强调。有鉴于此,有人主张"理解气候变化的政治经济学对于解决此问题极其重要"。[169]

同时气候变化的影响并非于全球均匀分布,以及产生人为气候变化因素最少的穷人却遭到最不平等的待遇,而将气候变化问题与经济发展研究产生联系,[170][171]因此催生出各种计划以及目的为应对气候变化和促进发展的政策。[172][173]虽然人们在此问题的国际谈判方面已非常尽力,但有人认为将气候变化与经济发展联系起来的许多理论、辩论、证据收集和施行在很大程度上都假定一非政治性和线性的政策过程。[174]在此背景下,研究人员Tanner和Allouche(2011年)提出建议,气候变化倡议必须明确认识到在投入、过程和结果方面的政治经济学,以便在有效性、效率和公平之间找到平衡。[174]

最早时,所谓"政治经济学"基本上与经济学同义,[175]而现在它已成为一个难以捉摸的名词,通常指的是运用集体或政治过程以制定公共经济决策的研究工作。[176]在气候变化领域,研究人员Tanner和Allouche(2011年)将政治经济学定义为"不同群体在不同规模上将思想、权力和资源概念化、协商和实施的过程"。[174]虽然目前已有大量关于环境政策的政治经济学文献来解释环境计划在有效保护环境方面的"政治失败"结果,[176]但利用政治经济学对气候变化的具体问题进行系统性的分析却相对有限。

迫切需要考量和理解气候变化的政治经济成因,源于气候变化问题本身的特殊属性。

这些特性如下列:

- 气候变化的跨部门性质:气候变化议题通常涉及不同部门,而经常需要将气候变化政策纳入其他政策领域。[84]因牵涉到复杂的治理过程及涉及不同的参与者,需在多个层面上解决。[177]这类相互作用导致过程中具有多重和重叠的概念、谈判和治理问题,而需对政治经济进程有所理解。[174]

- 将气候变化单纯视为一种"全球"议题的错误看法:气候变化倡议和治理方法往往着眼于全球推动。虽然制定有国际协议,而见证全球政治行动的进步,但这种全球主导的气候变化治理可能无法为特定国家或次国家个体提供足够的弹性。而从发展的角度来看,公平和全球环境正义议题需要一个公平的国际制度,可同时防止气候变化对贫穷者的影响。 因此气候变化不仅是一场需要国际政治参与的全球危机,也是种对国家或地方政府的挑战。对气候变化政治经济学的理解可用来解释国际倡议在特定国家和次国家政策情景下的制定和转化,而为应对气候变化和实现环境正义提供一重要概念。[174]

- 气候融资的成长:近年来于气候变化领域中的资金流动开始增加,融资机制有所开展。在墨西哥坎昆举行的2010年联合国气候变化大会,呼吁创立绿色气候基金,由发达国家向发展中国家提供大量资金,以支持调适和缓解技术。资金将透过双边和多边官方发展援助、全球环境基金、联合国气候变化纲要公约等多种管道转移。[178]此外也有越来越多的公共资金为发展中国家应对气候变化提供更大的助力。例如气候韧性试点计划(Pilot Program for Climate Resilience),目的在为一些低收入国家制定综合和扩大规模的气候变化调适方法,及为未来资金流动预作准备。除发展中国家和发达国家对"共同但有区别的责任(CBDR)概念"有不同的解释之外,气候变化资金的挹注也可能会改变对发展中国家的传统援助机制。[179][180]发展中国家因而必须改变治理结构,将传统的捐赠与受援关系扬弃。在这类情景中,了解气候变化领域资金流动的政治经济过程对于有效的管理资源转移和应对气候变化会非常重要。[174]

- 在不同意识形态下应对气候变化:由于当今将科学视为主要政策驱动力,气候变化领域中的许多政策和行动都集中在标准化治理和规划系统、线性政策流程、易于转让的技术、经济合理性以及科学技术克服资源差距的能力。[181]因而人们通常偏向使用技术主导的方法,遵循非政治性的方式应对气候变化。但由于各地本有不同意识形态的世界观,而会导致在气候变化解决方案的认知上有很大分歧,这也会对应对的决策产生很大影响。[182]从政治经济学的角度探讨这些问题能提供更好的理解"应对气候变化中的政治和决策过程的复杂性、调解资源争夺的权力关系以及促进技术采用的条件"的机会。[174]

- 未将环境与经济权衡的调适政策列入考虑会带来意想不到的负面后果:要能成功调适气候变化,需要把相互竞争的经济、社会和政治利益因素予以平衡。缺乏这种平衡,所造成的意料之外的后果可能会抵消施行的好处。例如坦桑尼亚保护珊瑚礁的努力反迫使当地村民从传统的捕鱼活动转向产生更多温室气体排放的农业活动。[183]

政治经济学在理解和应对气候变化方面的作用也建立在与国内社会政治约束相关的关键问题上:[169]

- 脆弱国家的问题:所谓脆弱国家的定义是表现不佳、冲突和/或冲突后的国家,通常其无法有效利用气候变化的援助。权力和社会公平问题将气候变化影响加剧,而全球对脆弱国家的功能失调关注不够。透过研究脆弱国家的问题,可提高对长期存在的能力和韧性限制因素的认识,而能更佳处理气候变化造成的能力脆弱、建国和冲突等问题。

- 非正式治理:在许多表现不佳的国家,有关国家资源分配和使用相关的决策并非来自代表平等与法律的国家机构,而是由非正式关系和私人激励因素所驱动。这类社会结构中的非正式治理会阻碍政治体制和结构合理运作,而阻碍对气候变化的有效应对。因此适合的国内机构和激励措施对于改革也非常重要。

- 难以进行社会变革:由于一系列长期的集体问题,开发不足国家在发展上进行变革的步调会极为缓慢,包括社会无力共同进行改善福祉、缺乏技术和社会独创性、对创新与变革的抵制和排斥等。[169]这些问题大幅阻碍气候变化的进程。透过政治经济学角度看待这类国家,有助于理解和创造促进转型和发展的动力,为实施气候变化调适预定进程奠定基础。

研究人员Brandt和Svendsen(2003年)[184]在研究欧盟实施京都议定书减排目标的政策工具选择时,采用研究人员Hillman(1982年)[185]所创政治支持函数模型的政治经济学框架。在此框架中,气候变化政策是由利害相关者的相对实力来决定。透过研究不同利益团体(即工业团体、消费者团体和环境团体)的不同目标,研究者为欧盟气候变化政策工具选择之间的复杂相互作用,特别是由征收绿色税收转换到依循祖父条款的排放许可制度(即对某些产业提供免费许可制度,可能比碳税或碳权拍卖制度更易获得强大的政治支持,而促使欧盟调高减排目标水平)。

国际复兴开发银行(EBRD)于2011年发表的一份报告,采用政治经济学方法来解释一些国家采取某些气候变化政策而另一些国家则否,特别是在经济转型地区的国家中(例如东欧与中亚,由计划经济转为市场经济)。[186]这份报告就不同政治经济面分析其气候变化政策,以了解推动许多转型经济气候变化缓解成果的可能因素。主要结论如下:

- 民主水平本身并非采用气候变化政策的主要驱动力,表示对全球气候变化减缓程度的期望不一定会受到特定国家政治体制的局限。

- 公众知识由各种因素形成,包括特定国家的气候变化威胁、国家教育水平和自由媒体的存在,是采用气候变化政策的关键因素,因为公众对气候变化了解更深,更有可能采用气候变化政策。因此重点应放在提高公众对气候变化威胁的认识,并防止许多转型经济体中有资讯不对等的缺失。

- 排放强度高的产业拥有较大实力时,是采用气候变化政策的主要障碍,它们在一定程度上会造成资讯不对等。因而需要引入有效的激励机制,让这类产业朝低排放强度模式转型。有效的手段包括能源定价改革和引入国际碳交易机制。

- 转型地区国家如能在减排上取得领先地位,就能在国际上享有竞争优势,进而提升国内政权的合法性,并借由发展绿色产业以克服经济上的固有弱点,甚至可在全球经济危机中找到新的契机。

研究人员Tanner和Allouche(2011年)[174]在他们撰写的报告中提出一个新的概念和方法框架,来分析气候变化的政治经济学,这个框架着重于思想、权力和资源如何影响气候变化政策的制定过程和最终结果。新的政治经济学方法预计将超越国际发展机构为分析气候变化措施而制定的政治经济工具,[187][188][189]旧有工具忽视思想和意识形态决定政策结果的方式(见本文末附表) [190]报告撰写者假设思想、权力和资源这三个概念在气候变化政治经济政策过程的某一阶段会分居主导地位,"思想和意识形态在概念化阶段占主导地位,权力在谈判过程中占主导地位,而资源、机构能力和治理在施行阶段占主导地位"。[174]有人认为这些要素对于制定国际气候变化倡议及将其转化为国家和地方政策时会具有举足轻重的地位。

| 过程 | 传统方式 | 新方式 |

|---|---|---|

| 政策流程 | 根据证据的线性思维 | 根据意识形态、参与者与潜力关系的复杂性思考 |

| 主要面向 | 全球及国家间 | 将国际性转化为个别国家及次国家层级 |

| 对于气候变化科学及研究 | 作为制定政策的客观资料 | 社会建构论与科学叙事 |

| 资源短缺与贫穷 | 分配结果(关注最终资源流往何处) | 调解竞争性资源诉求的政治程序(达成各方都能接受的政策方案) |

| 决定 | 集体/理性选择,包含寻租行为 | 意识形态驱动因素与诱因,包含权力关系 |

参见

注释

参考文献

延伸阅读

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.