Ajivica (em sânscrito; IAST: Ājīvika) é uma das escolas násticas ou "heterodoxas" da filosofia indiana.[5][6][7][8] Acredita-se que foi fundado no século V a.C. por Makkhali Gosāla, foi um movimento Xrâmana e um grande rival da religião védica, do budismo primitivo e do jainismo.[5][6][9] Os ajivicas eram renunciantes organizados que formavam comunidades discretas.[5][6] [10] A identidade precisa dos ajivicas não é bem conhecida, e não está claro se eles eram uma seita divergente dos budistas ou dos jainistas.[11]

As escrituras originais da escola de filosofia Ajivica podem ter existido, mas atualmente estão indisponíveis e provavelmente perdidas.[5][6] Suas teorias são extraídas de menções de ajivicas nas fontes secundárias da literatura indiana antiga.[5][6] [12] As descrições mais antigas dos fatalistas ajivicas e seu fundador Gosala podem ser encontradas nas escrituras budistas e jainistas da Índia antiga.[5][6][13] Os estudiosos questionam se a filosofia ajivica foi resumida de forma justa e completa nessas fontes secundárias, pois foram escritas por grupos (como os budistas e jainistas) competindo e adversários da filosofia e das práticas religiosas dos ajivicas.[6][14] Portanto, é provável que muitas das informações disponíveis sobre os ajivicas sejam imprecisas até certo ponto, e as caracterizações deles devem ser consideradas cuidadosa e criticamente.[6]

A escola Ajivica é conhecida por sua doutrina Niyati ("destino") de fatalismo absoluto ou determinismo,[6][8][13][15] a premissa de que não há livre arbítrio, que tudo o que aconteceu, está acontecendo e acontecerá é inteiramente preordenado e uma função de princípios cósmicos.[6][8] [12] O destino predeterminado dos seres vivos e a impossibilidade de alcançar a liberação (moksha) do eterno ciclo de nascimento, morte e renascimento foi a principal doutrina filosófica e metafísica distinta de sua escola de filosofia indiana.[6][13][15] Ājīvikas consideraram ainda a doutrina do carma como uma falácia.[16] A metafísica ajivica incluía uma teoria de átomos que mais tarde foi adaptada na escola vaisesica, onde tudo era composto de átomos, qualidades surgidas de agregados de átomos, mas a agregação e a natureza desses átomos eram predeterminadas por leis e forças cósmicas.[6] [17] Os ajivicas eram principalmente considerados ateus.[18] Eles acreditavam que em cada ser vivo existe um atmã — uma premissa central do hinduísmo e do jainismo.[19][20][21]

A filosofia ajivica, também conhecida como ajiviquismo na erudição ocidental,[6] atingiu o auge de sua popularidade durante o governo do imperador máuria Bindusara, por volta do século IV a.C. Esta escola de pensamento depois declinou, mas sobreviveu por quase dois mil anos através dos séculos XIII e XIV d.C. nos estados do sul da Índia de Carnataca e Tâmil Nadu.[5][7][16][22] A filosofia ajivica, juntamente com a filosofia charvaca, atraiu mais as classes guerreiras, industriais e mercantis da antiga sociedade indiana.[23]

Etimologia e significado

Sânscrito

Ājīvika significa "Seguidor do Caminho da Vida".[5] Ajivica (em prácrito: 𑀆𑀚𑀻𑀯𑀺𑀓, ājīvika;[24] em sânscrito: आजीविक, ājīvika) ou adivica (em prácrito: 𑀆𑀤𑀻𑀯𑀺𑀓, ādīvika)[25] são ambos derivados do sânscrito आजीव (ājīv) que significa literalmente "subsistência, ao longo da vida, modo de vida".[26][27] O termo ajivica "aqueles que seguem regras especiais em relação ao modo de vida", às vezes conotando "mendicantes religiosos" em textos antigos em sânscrito e páli.[7] [12]

O nome "ajivica", para toda uma filosofia, ressoa com sua crença central em "sem livre arbítrio" e niyati completo, literalmente "ordem interna das coisas, autocontrole, predeterminismo", levando à premissa de que a boa vida simples não é um meio para a salvação ou moksha, apenas um meio para o verdadeiro sustento, profissão predeterminada e modo de vida.[27][28] O nome veio a implicar aquela escola de filosofia indiana que vivia um bom e simples modo de vida mendicante por si mesmo e como parte de suas crenças predeterministas, e não por causa da vida após a morte ou motivado por qualquer razões soteriológicas.[12][27]

Alguns estudiosos escrevem "ajivica" como "ajivaca".[29]

Referências

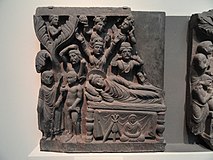

- Balcerowicz, Piotr (2016). «A Religious Centre and the Art of the Ājīvikas». Early Asceticism in India: Ājīvikism and Jainism. Col: Routledge Advances in Jaina Studies 1st ed. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 278–281. ISBN 9781317538530

- Marianne Yaldiz, Herbert Härtel, Along the Ancient Silk Routes: Central Asian Art from the West Berlin State Museums; an Exhibition Lent by the Museum Für Indische Kunst, Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982, p. 78

- Johnson, W. J. (2009). «Ājīvika». A Dictionary of Hinduism 1st ed. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191726705.

Ājīvika (‘Follower of the Way of Life’): Name given to members of a heterodox ascetic order, apparently founded at the same time as the Buddhist and Jaina orders, and now extinct, although active in South India as late as the 13th century. No first-hand record survives of Ājīvika doctrines, so what is known about them is derived largely from the accounts of their rivals. According to Jaina sources, the Ājīvika's founder, Makkhali Gosāla, was for six years a disciple and companion of the Jina-to-be, Mahāvīra, until they fell out.

- Balcerowicz, Piotr (2016). «Determinism, Ājīvikas, and Jainism». Early Asceticism in India: Ājīvikism and Jainism. Col: Routledge Advances in Jaina Studies 1st ed. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 136–174. ISBN 9781317538530.

The Ājīvikas' doctrinal signature was indubitably the idea of determinism and fate, which traditionally incorporated four elements: the doctrine of destiny (niyati-vāda), the doctrine of predetermined concurrence of factors (saṅgati-vāda), the doctrine of intrinsic nature (svabhāva-vāda), occasionally also linked to materialists, and the doctrine of fate (daiva-vāda), or simply fatalism. The Ājīvikas' emphasis on fate and determinism was so profound that later sources would consistently refer to them as niyati-vādins, or ‘the propounders of the doctrine of destiny’.

- Natalia Isaeva (1993), Shankara and Indian Philosophy, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791412817, pages 20-23

- James Lochtefeld, "Ajivika", The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A–M, Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-0823931798, page 22

- Jeffrey D Long (2009), Jainism: An Introduction, Macmillan, ISBN 978-1845116255, page 199

- Basham 1951, pp. 145-146.

- Fogelin, Lars (2015). An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism (em inglês). [S.l.]: Oxford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780199948222

- Basham 1951, Chapter 1.

- Basham, Arthur L. (1981) [1951]. «Chapter XII: Niyati». History and Doctrines of the Ājīvikas, a Vanished Indian Religion. Col: Lala L. S. Jain Series 1st ed. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 224–238. ISBN 9788120812048. OCLC 633493794.

The fundamental principle of Ājīvika philosophy was Fate, usually called Niyati. Buddhist and Jaina sources agree that Gosāla was a rigid determinist, who exalted Niyati to the status of the motive factor of the universe and the sole agent of all phenomenal change. This is quite clear in our locus classicus, the Samaññaphala Sutta. Sin and suffering, attributed by other sects to the laws of karma, the result of evil committed in the previous lives or in the present one, were declared by Gosāla to be without cause or basis, other, presumably, than the force of destiny. Similarly, the escape from evil, the working off of accumulated evil karma, was likewise without cause or basis.

- Paul Dundas (2002), The Jains (The Library of Religious Beliefs and Practices), Routledge, ISBN 978-0415266055, pages 28-30

- Leaman, Oliver, ed. (1999). «Fatalism». Key Concepts in Eastern Philosophy. Col: Routledge Key Guides 1st ed. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 80–81. ISBN 9780415173636.

Fatalism. Some of the teachings of Indian philosophy are fatalistic. For example, the Ajivika school argued that fate (nyati) governs both the cycle of birth and rebirth, and also individual lives. Suffering is not attributed to past actions, but just takes place without any cause or rationale, as does relief from suffering. There is nothing we can do to achieve moksha, we just have to hope that all will go well with us. [...] But the Ajivikas were committed to asceticism, and they justified this in terms of its practice being just as determined by fate as anything else.

- Basham 1951, pp. 262-270.

- Johannes Quack (2014), The Oxford Handbook of Atheism (Editors: Stephen Bullivant, Michael Ruse), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199644650, page 654

- Analayo (2004), Satipaṭṭhāna: The Direct Path to Realization, ISBN 978-1899579549, pp. 207-208

- Basham 1951, pp. 240-261.

- Basham 1951, pp. 270-273.

- Arthur Basham, Kenneth Zysk (1991), The Origins and Development of Classical Hinduism, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195073492, Chapter 4

- DM Riepe (1996), Naturalistic Tradition in Indian Thought, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120812932, pages 39-40

- Hultzsch, Eugen (1925). Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (em sânscrito). [S.l.: s.n.] p. 132

- Senart (1876). Inscriptions Of Piyadasi Tome Second (em inglês). [S.l.: s.n.] pp. 209–210

- A Hoernle, Encyclopædia of Religion and Ethics, Volume 1, p. PA259, no Google Livros, Editor: James Hastings, Charles Scribner & Sons, Edinburgh, pages 259-268

- John R. Hinnells (1995), Ajivaka, A New Dictionary of Religions, Wiley-Blackwell Reference, ISBN 978-0631181392

Bibliografia

Ligações externas

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.