Geologie van de Himalaya

Van Wikipedia, de vrije encyclopedie

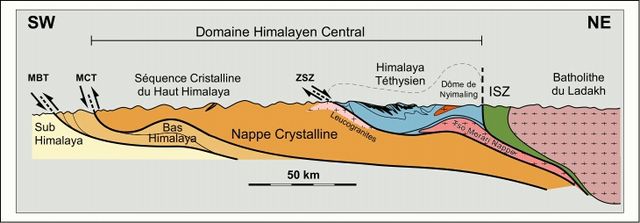

De geologie van de Himalaya is een recent voorbeeld van de werking van de Alpiene orogenese, een proces van gebergtevorming dat zich tijdens het Tertiair heeft afgespeeld. De Himalaya die zich 2900 km uitstrekt langs de grens van Pakistan, India en Tibet is het gevolg van voortdurende plaattektonische bewegingen als resultaat van de botsing van twee continentale platen (de Indische en de Euraziatische). De Himalaya is een relatief zeer jong gebergte (gevormd vanaf 50 Ma). De vorm van het gebergte wordt bepaald door het proces van uplift gevolgd door afbraak door verwering en erosie.

Plaattektonische reconstructie

Samenvatten

Perspectief

De volgende paleogeografische reconstructie is vooral gebaseerd op: Besse et al., 1984; Patriat en Achache, 1984; Dewey et al. 1989; Brookfield, 1993; Ricou, 1994; Rowley, 1996; Stampfli et al. 1998.

In het late Precambrium en het Palaeozoïcum was het Indiase continent deel van Gondwana en werd door de Paleotethys van Eurazië gescheiden. (Fig. 1). In deze periode werd het noordelijk deel van India geraakt door de "Cambro-Ordovicische Pan-Afrikaanse gebeurtenis", die wordt gekenmerkt door een discordantie tussen Ordovicische continentale conglomeraten en de onderliggende mariene sedimenten uit het Cambrium. Granietlichamen gedateerd rond 500 Ma worden aan dezelfde tektonische gebeurtenis toegeschreven.

In het vroege Carboon begon een vroeg stadium van rifting tussen het Indiase continent en de Cimmerian Superterranes. In het vroege Perm zou deze scheuring zich ontwikkelen in de Neotethys oceaan (Fig. 2). Daarna scheidden de Cimmerian Superterranes zich af van Gondwana naar het noorden. Het tegenwoordige Iran, Afghanistan en Tibet komen gedeeltelijk voort uit deze terranes.

In het boven-Trias (210 Ma) brak Gondwana in twee delen uiteen. Het Indiase continent ging deel uitmaken van Oost Gondwana, samen met Australië en Antarctica. De formatie van de oceanische korst kwam pas goed op gang in het Jura (160 - 155 Ma). De Indische plaat brak toen af van Australië en Antarctica in het vroege Krijt (130 - 125 Ma) met de opening van de "Zuid Indische Oceaan" (Fig. 3).

In het Late Krijt (84 Ma) begon de Indische plaat zijn snelle beweging naar het noorden (een gemiddelde snelheid van 16 cm per jaar), en legde een afstand af van 6000 km, totdat het collideerde met het noordwestelijke deel van Eurazië in het vroege Eoceen (48 - 52 Ma). Sindsdien blijft het Indiase continent naar het noorden klimmen met een langzamere snelheid van ~ 5 cm/jaar. Het is daarbij topografisch ongeveer 2400 km in Eurazië binnengedrongen, waarbij het een roterende beweging van 33° tegen de klok in maakt. (Fig. 4).

Waterhuishouding

Het Himalaya-gebied is de watertoren van Azië: het levert vers water voor meer dan een vijfde van de wereldbevolking, en het zorgt voor een kwart van het sediment in de wereld. Topografisch bevat de streek veel records: de hoogste stijging (bijna 1 cm/jaar bij de Nanga Parbat), de hoogste berg (8848 m, de Mount Everest of Chomolangma), de bron van enkele van de grootste rivieren in de wereld en de hoogste concentratie gletsjers buiten de poolstreken. In het Sanskriet heet het gebied dan ook: de woonplaats van de sneeuw.

Referenties

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.