Loading AI tools

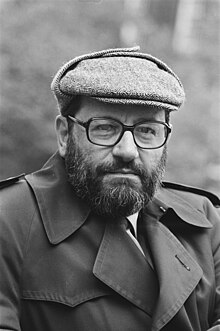

Umberto Eco (5 January 1932 – 19 February 2016) was an Italian philosopher, semiotician, essayist, literary critic, and novelist, most famous for his novel The Name of the Rose (1980), an intellectual mystery combining semiotics in fiction, biblical analysis, medieval studies and literary theory.

- See also:

- Foucault's Pendulum (1989)

- The Island of the Day Before (1994)

- Not long ago, if you wanted to seize political power in a country you had merely to control the army and the police. Today it is only in the most backward countries that fascist generals, in carrying out a coup d'état, still use tanks. If a country has reached a high degree of industrialization the whole scene changes. The day after the fall of Khrushchev, the editors of Pravda, Izvestiia, the heads of the radio and television were replaced; the army wasn't called out. Today a country belongs to the person who controls communications.

- Il costume di casa (1973); as translated in Travels in Hyperreality (1986)

- Semiotics is in principle the discipline studying everything which can be used in order to lie. If something cannot be used to tell a lie, conversely it cannot be used to tell the truth: it cannot in fact be used "to tell" at all.

- Trattato di semiotica generale (1975); [A Theory of Semiotics] (1976)

- Variant: A sign is anything that can be used to tell a lie.

- The basic principle [of hermetic drift semiotics] is not only that the similar can be known through the similar but also that from similarity to similarity everything can be connected with everything else, so that everything can be in turn either the expression or the content of any other thing.

- U. Eco (1990), The limits of Intepretation, as quoted in Thomas A. Sebeok, Jean Umiker-Sebeok (2020), The Semiotic Web 1991: Biosemiotics.

- A democratic civilization will save itself only if it makes the language of the image into a stimulus for critical reflection — not an invitation for hypnosis.

- "Can Television Teach?" in Screen Education 31 (1979), p. 12

- Epistemological thinkers connected with quantum methodology have rightly warned against an ingenuous transposition of physical categories into the fields of ethics and psychology (for example. the identification of indeterminacy with moral freedom). Hence, it would not be justified to understand my formulation as making an analogy between the structures of the work of art and the supposed structures of the world. Indeterminacy, complementarity, noncausality are not modes of being in the physical world, but systems for describing it in a convenient way. The relationship which concerns my exposition is not the supposed nexus between an "ontological" situation and a morphological feature in the work of art, but the relation between an operative procedure for explaining physical processes and an operative procedure for explaining the processes of artistic production and reception. In other words, the relationship between a scientific methodology and a poetics.

- The Role of the Reader : Explorations in the Semiotics of Texts (1979), Part 1: Open, Ch. 1 : The Poetics of the Open Work, endnote 9, p. 66; later published amidst extended and developed translations of Opera aperta (1962), in The Open Work (1989) as translated by Anna Cancogni, Ch. 1 : The Poetics of the Open Work, endnote 9, p. 251

- I started to write [The Name of the Rose] in March of 1978, moved by a seminal idea. I wanted to poison a monk.

- Quoted in Myriem Bouzaher's introduction to the French version of The Name of the Rose, Postille al Nome della Rosa, Page 18 (1985)

- In the United States, politics is a profession, whereas in Europe it is a right and a duty.

- Preface to the American edition of Travels in Hyperreality (1986)

- The real hero is always a hero by mistake; he dreams of being an honest coward like everybody else. If it had been possible he would have settled the matter otherwise, and without bloodshed. He doesn't boast of his own death or of others'. But he does not repent. He suffers and keeps his mouth shut; if anything, others then exploit him, making him a myth, while he, the man worthy of esteem, was only a poor creature who reacted with dignity and courage in an event bigger than he was.

- "Why Are They Laughing In Those Cages?", in Travels in Hyperreality : Essays (1986), Ch. III : The Gods of the Underworld, p. 122

- The language of Europe is translation.

- To read fiction means to play a game by which we give sense to the immensity of things that happened, are happening, or will happen in the actual world. By reading narrative, we escape the anxiety that attacks us when we try to say something true about the world. This is the consoling function of narrative — the reason people tell stories, and have told stories from the beginning of time.

- Six Walks in the Fictional Woods (1994) Chapter Four: "Possible Woods"

- How should we deal with intrusions of fiction into life, now that we have seen the historical impact that this phenomenon can have? … Reflecting on these complex relationships between reader and story, fiction and life, can constitute a form of therapy against the sleep of reason, which generates monsters.

- Six Walks in the Fictional Woods (1994) Chapter Six: "Fictional Protocols"

- I don't even have an E-mail address. I have reached an age where my main purpose is not to receive messages.

- After all, the cultivated person's first duty is to be always prepared to rewrite the encyclopaedia.

- Serendipities: Language and Lunacy (1998)

- I don't miss my youth. I'm glad I had one, but I wouldn't like to start over.

- "On the Disadvantages and Advantages of Death" in La mort et l'immortalié, edited by Frédéric Lenoir (2004)

- I am mimetic. If I write a book set in the seventeenth century, I write in a Baroque style. If I’m writing a book set in a newspaper office, I write in Journalese.

- quoted in Marco Belpoliti, "Umberto Eco: How I Wrote my Books" (2015)

The Name of the Rose (1980)

- Il nome della rosa (1980); The Name of the Rose (1983)

- There are magic moments, involving great physical fatigue and intense motor excitement, that produce visions of people known in the past. As I learned later from the delightful little book of the Abbé de Bucquoy, there are also visions of books as yet unwritten.

- A monk should surely love his books with humility, wishing their good and not the glory of his own curiosity; but what the temptation of adultery is for laymen and the yearning for riches is for secular ecclesiastics, the seduction of knowledge is for monks.

- Books are not made to be believed, but to be subjected to inquiry. When we consider a book, we mustn't ask ourselves what it says but what it means...

- William of Baskerville

- Because learning does not consist only of knowing what we must or we can do, but also of knowing what we could do and perhaps should not do.

- "That man is … odd," I dared say to William.

"He is, or has been, in many ways a great man. But for this very reason he is odd. It is only petty men who seem normal."

- We live for books.

- Benno of Uppsala

- The Devil is not the Prince of Matter; the Devil is the arrogance of the spirit, faith without smile, truth that is never seized by doubt. The Devil is grim because he knows where he is going, and, in moving, he always returns whence he came.

- William of Baskerville

- The hand of God creates; it does not conceal.

- William of Baskerville

- Stat rosa pristina nomine, nomina nuda tenemus.

- Adso

- There is only one thing that arouses animals more than pleasure, and that is pain. Under torture you are as if under the dominion of those grasses that produce visions. Everything you have heard told, everything you have read returns to your mind, as if you were being transported, not toward heaven, but towards hell. Under torture you say not only what the inquisitor wants, but also what you imagine might please him, because a bond (this, truly, diabolical) is established between you and him.

- Temi, Adso, i profeti e coloro disposti a morire per la verità, ché di solito fan morire moltissimo con loro, spesso prima di loro, talvolta al posto loro.

- Fear prophets, Adso, and those prepared to die for the truth, for as a rule they make many others die with them, often before them, at times instead of them.

- William of Baskerville

Semiotics and the Philosophy of Language (1984)

- Semiotica e filosofia del linguaggio (1984)

- The sign is usually considered as a correlation between a signifier and a signified (or between expression and content) and therefore as an action between pairs. Semiosis is, according to Peirce, "an action, or influence, which is, or involves, an operation of three subjects, such as a sign, its object, and its interpretant, this tri-relative influence not being in any way resolvable into an action between pairs".

- [O] : Introduction, O.I.

- The principle of interpretation says that "a sign is something by knowing which we know something more" (Peirce). The Peircean idea of semiosis is the idea of an infinite process of interpretation. It seems that the symbolic mode is the paramount example of this possibility.

However, interpretation is not reducible to the responses elicited by the textual strategies accorded to the symbolic mode. The interpretation of metaphors shifts from the univocality of catachreses to the open possibilities offered by inventive metaphors. Many texts have undoubtedly many possible senses, but it is still possible to decide which one has to be selected if one approaches the text in the light of a given topic, as well as it is possible to tell of certain texts how many isotopies they display.- [O] : Introduction, 0.2

- A specific semiotics is, or aims at being, the 'grammar' of a particular sign system, and proves to be successful insofar as it describes a given field of communicative phenomena as ruled by a system of signification. Thus there are 'grammars' of the American Sign Language, of traffic signals, of a playing-card 'matrix' for different games or of a particular game (for instance, poker). These systems can be studied from a syntactic, a semantic, or a pragmatic point of view.

- [O] : Introduction, 0.4

- Every specific semiotics (as every science) is concerned with general epistemological problems. It has to posit its own theoretical object, according to criteria of pertinence, in order to account for an otherwise disordered field of empirical data; and the researcher must be aware of the underlying philosophical assumptions that influence its choice and its criteria for relevance. Like every science, even a specific semiotics ought to take into account a sort of 'uncertainty principle' (as anthropologists must be aware of the fact that their presence as observers can disturb the normal course of the behavioral phenomena they observe). Notwithstanding, a specific semiotics can aspire to a 'scientific' status. Specific semiotics study phenomena that are reasonably independent of their observations.

- [O] : Introduction, 0.4

- Not every specific semiotics can claim to be like a natural science. In fact, every specific semiotics is at most a human science, and everybody knows how controversial such a notion still is. However, when cultural anthropology studies the kinship system in a certain society, it works upon a rather stable field of phenomena, can produce a theoretical object, and can make some prediction about the behavior of the members of this society. The same happens with a lexical analysis of the system of terms expressing kinship in the same society.

- [O] : Introduction, 0.4

- Signs are not empirical objects. Empirical objects become signs (or they are looked at as signs) only from the point of view of a philosophical decision.

- [O] : Introduction, 0.6

- When semiotics posits such concepts as 'sign', it does not act like a science; it acts like philosophy when it posits such abstractions as subject, good and evil, truth or revolution. Now, a philosophy is not a science, because its assertions cannot be empirically tested … Philosophical entities exist only insofar as they have been philosophically posited. Outside their philosophical framework, the empirical data that a philosophy organizes lose every possible unity and cohesion.

To walk, to make love, to sleep, to refrain from doing something, to give food to someone else, to eat roast beef on Friday — each is either a physical event or the absence of a physical event, or a relation between two or more physical events. However, each becomes an instance of good, bad, or neutral behavior within a given philosophical framework. Outside such a framework, to eat roast beef is radically different from making love, and making love is always the same sort of activity independent of the legal status of the partners. From a given philosophical point of view, both to eat roast beef on Friday and to make love to x can become instances of 'sin', whereas both to give food to someone and to make love to у can become instances of virtuous action.

Good or bad are theoretical stipulations according to which, by a philosophical decision, many scattered instances of the most different facts or acts become the same thing. It is interesting to remark that also the notions of 'object', 'phenomenon', or 'natural kind', as used by the natural sciences, share the same philosophical nature. This is certainly not the case of specific semiotics or of a human science such as cultural anthropology.- [O] : Introduction, 0.6

- A philosophy has a practical power: it contributes to the changing of the world. This practical power has nothing to do with the engineering power that in the discussion above I attributed to sciences, including specific semiotics. A science can study either an animal species or the logic of road signals, without necessarily determining their transformation. There is a certain 'distance' between the descriptive stage and the decision, let us say, to improve a species through genetic engineering or to improve a signaling system by reducing or increasing the number of its pertinent elements.

On the contrary, it was the philosophical position of the modern notion of thinking subject that led Western culture to think and to behave in terms of subjectivity. It was the position of notions such as class struggle and revolution that led people to behave in terms of class, and not only to make revolutions but also to decide, on the grounds of this philosophical concept, which social turmoils or riots of the past were or were not a revolution. Since a philosophy has this practical power, it cannot have a predictive power. It cannot predict what would happen if the world were as it described it. Its power is not the direct result of an act of engineering performed on the basis of a more or less neutral description of independent data.- [O] : Introduction, 0.7

- A philosophy does not play its role as an actor during a recital; it interacts with other philosophies and with other facts, and it cannot know the results of the interaction between itself and other world visions. World visions can conceive of everything, except alternative world visions, if not in order to criticize them and to show their inconsistency. Affected as they are by a constitutive solipsism, philosophies can say everything about the world they design and very little about the world they help to construct.

- [O] : Introduction, 0.7

- A general semiotics studies the whole of the human signifying activity — languages — and languages are what constitutes human beings as such, that is, as semiotic animals. It studies and describes languages through languages. By studying the human signifying activity it influences its course. A general semiotics transforms, for the very fact of its theoretical claim, its own object.

- [O] : Introduction, 0.8

- I am not saying that philosophies, since they are speculative, speak of the nonexistent. When they say 'subject' or 'class struggle' or 'dialectics', they always point to something that should have been defined and posited in some way. Philosophies can be judged, at most, on the grounds of the perspicacity with which they decide that something is worthy of becoming the starting point for a global explanatory hypothesis. Thus I do not think that the sign (or any other suitable object for a general semiotics) is a mere figment.

- [O] : Introduction, 0.8

- Certainly, the categories posited by a general semiotics can prove their power insofar as they provide a satisfactory working hypothesis to specific semiotics. However, they can also allow one to look at the whole of human activity from a coherent point of view. To see human beings as signifying animals — even outside the practice of verbal language — and to see that their ability to produce and to interpret signs, as well as their ability to draw inferences, is rooted in the same cognitive structures, represent a way to give form to our experience. There are obviously other philosophical approaches, but I think that this one deserves some effort.

- [O] : Introduction, 0.8

- The sign is a gesture produced with the intention of communicating, that is, in order to transmit one's representation or inner state to another being. The existence of a certain rule (a code) enabling both the sender and the addressee to understand the manifestation in the same way must, of course, be presupposed if the transmission is to be successful; in this sense, navy flags, street signs, signboards, trademarks, labels, emblems, coats of arms, and letters are taken to be signs.

- [I] Signs, 1.2.2

- As subjects, we are what the shape of the world produced by signs makes us become.

Perhaps we are, somewhere, the deep impulse which generates semiosis. And yet we recognize ourselves only as semiosis in progress, signifying systems and communicational processes. The map of semiosis, as defined at a given stage of historical development (with the debris carried over from previous semiosis), tells us who we are and what (or how) we think.- [I] Signs, 1.13 : Sign and subject

- A sign is not only something which stands for something else; it is also something that can and must be interpreted. The criterion of interpretability allows us to start from a given sign to cover, step by step, the whole universe of semiosis.

- [2] Dictionary vs. Encyclopedia, 2.1 : Porphyry strikes back, 2.1.1 : Is a definition an interpretation?

- No algorithm exists for the metaphor, nor can a metaphor be produced by means of a computer's precise instructions, no matter what the volume of organized information to be fed in. The success of a metaphor is a function of the sociocultural format of the interpreting subjects' encyclopedia. In this perspective, metaphors are produced solely on the basis of a rich cultural framework, on the basis, that is, of a universe of content that is already organized into networks of interpretants, which decide (semiotically) the identities and differences of properties. At the same time, content universe, whose format postulates itself not as rigidly hierarchized but, rather, according to Model Q, alone derives from the metaphorical production and interpretation the opportunity to restructure itself into new nodes of similarity and dissimilarity.

- [3] Metaphor, 3.12. Conclusions

- What is a symbol? Etymologically speaking, the word σύμβολον comes from σνμβάλλω, to throw-with, to make something coincide with something else: a symbol was originally an identification mark made up of two halves of a coin or of a medal. Two halves of the same thing, either one standing for the other, both becoming, however, fully effective only when they matched to make up, again, the original whole. … in the original concept of symbol, there is the suggestion of a final recomposition. Etymologies, however, do not necessarily tell the truth — or, at least, they tell the truth, in terms of historical, not of structural, semantics. What is frequently appreciated in many so-called symbols is exactly their vagueness, their openness, their fruitful ineffectiveness to express a 'final' meaning, so that with symbols and by symbols one indicates what is always beyond one's reach.

- [4] Symbol

- Scholem … says that Jewish mystics have always tried to project their own thought into the biblical texts; as a matter of fact, every unexpressible reading of a symbolic machinery depends on such a projective attitude. In the reading of the Holy Text according to the symbolic mode, "letters and names are not conventional means of communication. They are far more. Each one of them represents a concentration of energy and expresses a wealth of meaning which cannot be translated, or not fully at least, into human language" [On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism (1960); Eng. tr., p. 36]. For the Kabalist, the fact that God expresses Himself, even though His utterances are beyond any human insight, is more important than any specific and coded meaning His words can convey.

The Zohar says that "in any word shine a thousand lights" (3.202a). The unlimitedness of the sense of a text is due to the free combinations of its signifiers, which in that text are linked together as they are only accidentally but which could be combined differently.- [4] Symbol, 4.4 : The symbolic mode, 4.4.4 : The Kabalistic drift

Ur-Fascism (1995)

- In The New York Review of Books (22 June 1995)

- Fascism became an all-purpose term because one can eliminate from a fascist regime one or more features, and it will still be recognizable as fascist. Take away imperialism from fascism and you still have Franco and Salazar. Take away colonialism and you still have the Balkan fascism of the Ustashes. Add to the Italian fascism a radical anti-capitalism (which never much fascinated Mussolini) and you have Ezra Pound. Add a cult of Celtic mythology and the Grail mysticism (completely alien to official fascism) and you have one of the most respected fascist gurus, Julius Evola... But in spite of this fuzziness, I think it is possible to outline a list of features that are typical of what I would like to call Ur-Fascism, or Eternal Fascism.

- [Ur-Fascism] depends on the cult of action for action's sake. Action being beautiful in itself, it must be taken before, or without, any previous reflection. Thinking is a form of emasculation. Therefore culture is suspect insofar as it is identified with critical attitudes. Distrust of the intellectual world has always been a symptom of Ur-Fascism, from Goering's alleged statement ("When I hear talk of culture I reach for my gun") to the frequent use of such expressions as "degenerate intellectuals," "eggheads," "effete snobs," "universities are a nest of reds." The official Fascist intellectuals were mainly engaged in attacking modern culture and the liberal intelligentsia for having betrayed traditional values.

- At the root of the Ur-Fascist psychology there is the obsession with a plot, possibly an international one. The followers must feel besieged. The easiest way to solve the plot is the appeal to xenophobia. But the plot must also come from the inside: Jews are usually the best target because they have the advantage of being at the same time inside and outside. In the US, a prominent instance of the plot obsession is to be found in Pat Robertson's The New World Order, but, as we have recently seen, there are many others.

- The followers must feel humiliated by the ostentatious wealth and force of their enemies. When I was a boy I was taught to think of Englishmen as the five-meal people. They ate more frequently than the poor but sober Italians. Jews are rich and help each other through a secret web of mutual assistance. However, the followers must be convinced that they can overwhelm the enemies. Thus, by a continuous shifting of rhetorical focus, the enemies are at the same time too strong and too weak.

- Elitism is a typical aspect of any reactionary ideology, insofar as it is fundamentally aristocratic, and aristocratic and militaristic elitism cruelly implies contempt for the weak. Ur-Fascism can only advocate a popular elitism. Every citizen belongs to the best people of the world, the members of the party are the best among the citizens, every citizen can (or ought to) become a member of the party. But there cannot be patricians without plebeians. In fact, the Leader, knowing that his power was not delegated to him democratically but was conquered by force, also knows that his force is based upon the weakness of the masses; they are so weak as to need and deserve a ruler. Since the group is hierarchically organized (according to a military model), every subordinate leader despises his own underlings, and each of them despises his inferiors. This reinforces the sense of mass elitism.

- Ur-Fascism is based upon a selective populism, a qualitative populism, one might say. In a democracy, the citizens have individual rights, but the citizens in their entirety have a political impact only from a quantitative point of view—one follows the decisions of the majority. For Ur-Fascism, however, individuals as individuals have no rights, and the People is conceived as a quality, a monolithic entity expressing the Common Will. Since no large quantity of human beings can have a common will, the Leader pretends to be their interpreter. Having lost their power of delegation, citizens do not act; they are only called on to play the role of the People. Thus the People is only a theatrical fiction. To have a good instance of qualitative populism we no longer need the Piazza Venezia in Rome or the Nuremberg Stadium. There is in our future a TV or Internet populism, in which the emotional response of a selected group of citizens can be presented and accepted as the Voice of the People.

- Ur-Fascism is still around us, sometimes in plainclothes. It would be so much easily for us, if there appeared on the scene somebody saying "I want to re-open Auschwitz, I want the Blackshirts to parade again in the Italian squares". Life is not that simple. Ur-Fascism can come back under the most innocent of disguises. Our duty is to uncover it and point the finger at any of its new instances — every day and in every part of the world.

Baudolino (2000)

- "A sack," Baudolino explained, like a man who knows a trade well, "is like a grape harvest: you have to divide the tasks. There are those who press the grapes, those who carry off the must in the tuns, those who cook for others, others who go to fetch the good wine from last year.... a sack is a serious job,"

- Chapter 2, "Baudolino meets Niketas Choniates"

- "The emperor of the Latins — who hasn't been a Latin himself since the days of Charlemagne — is the successor of the Roman emperors — the ones of Rome, I mean, not those of Constantinople. But to make sure he's emperor, he has to be crowned by the pope, because the law of Christ has swept away the false law, the law of liars. To be crowned by the pope, the emperor also has to be recognized by the cities of Italy, and each of them kind of goes his own way, so he has to be crowned king of Italy — provided, naturally, that the Teutonic princes have elected him. Is that clear?"

- Chapter 3, "Baudolino explains to Niketas what he wrote as a boy"

- "The Poet had, who had made a show of attaching no importance to this literary game (though it gnawed at his heart that he himself had not written such beautiful letters, provoking replies even more beautiful), and having no one with whom to fall in love, had fallen in love with the letters themselves — which, as Niketas remarked with a smile — was not surprising, since in youth we are prone to fall in love with love.

- Chapter 7, "Baudolino makes the Poet write love letters and poems to Beatrice"

- "There, Master Niketas," Baudolino said, "when I was not prey to the temptations of this world, I devoted my nights to imagining other worlds. ... There is nothing better than imagining other worlds," he said, "to forget the painful one we live in. At least so I thought then. I hadn't yet realized that, imagining other worlds, you end up changing this one."

The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana (2004)

- La Misteriosa Fiamma della Regina Loana (2004); The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana (2005)

- In short, to remember is to reconstruct in part on the basis of what we have learned or said since. That's normal, that's how we remember. I tell you this to encourage you to reactivate some of these profiles of excitation, instead of simply digging obsessively in an effort to find something that's already there, as shiny and new as you imagine it was when you first set it aside ... Remembering is a labor, not a luxury.

- In this world you either read or write, and writers write out of contempt for their colleagues, out of a desire to have something good to read once in a while.

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.