Zackie Achmat

South African activist, politician and film director From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

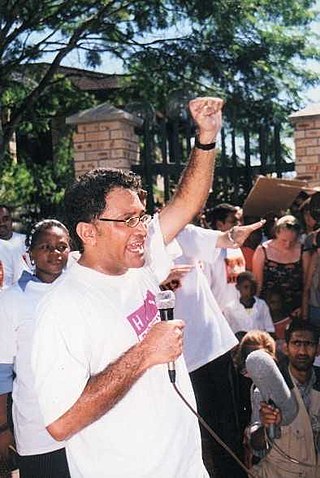

Abdurrazack "Zackie" Achmat (born 21 March 1962) is a South African activist and film director.[2][3][4] He is a co-founder the Treatment Action Campaign and known worldwide for his activism on behalf of people living with HIV and AIDS in South Africa. He served as board member and co-director of Ndifuna Ukwazi (Dare to Know),[5] an organisation which aims to build and support social justice organisations and leaders, and was the chairperson of Equal Education.[6][7] In 2024, he stood as independent candidate in the South African National Elections.[8] However, he did not garner enough support to secure a seat in parliament.[9]

Zackie Achmat | |

|---|---|

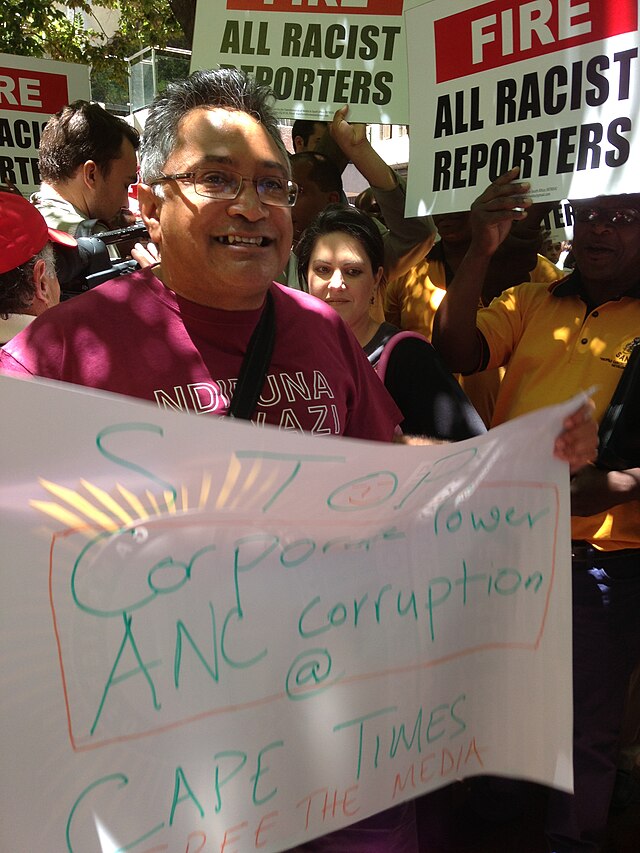

Achmat at an Open Society Foundation of South Africa event on police accountability in 2013 | |

| Born | 21 March 1962 Vrededorp, Johannesburg, South Africa |

| Nationality | South African |

| Alma mater | University of the Western Cape |

| Occupation(s) | Activist, film director |

| Employer | Ndifuna Ukwazi (Dare to Know) |

| Known for | HIV/AIDS activism |

| Political party | Independent |

| Board member of | Ndifuna Ukwazi (Dare to Know) Equal Education |

| Spouse | Dalli Weyers (m. 2008; div. 2011) |

| Parent(s) | Suleiman Achmat and Mymoena Adams[1] |

| Relatives | Taghmeda "Midi" Achmat (sister)[1] |

| Website | www |

Early life and education

Achmat was born in the Johannesburg suburb of Vrededorp to a Muslim Cape Malay family and grew up in the Cape Coloured community in Salt River during apartheid.[10][11] He was raised by his mother and his aunt who were both shop stewards for the Garment Workers Union.[4][3]

He worked as a sex worker as a teenager between 1977 and 1981. Later he would cite the income and opportunity it provided for intimacy and experimentation in exploring his sexuality as reasoning for entering the line of work.[12]

He did not matriculate but nevertheless graduated with a BA Hons degree in English literature from the University of the Western Cape in 1992 and studied filmmaking at the Cape Town Film School.[2][4][3]

Political activism

Summarize

Perspective

Achmat set fire to his school in Salt River in support of the 1976 student protests and was imprisoned several times during his youth for political activities.[13][14] He joined the African National Congress (ANC) in 1980 while serving time in prison.[15] Between 1985 and 1990 he was a member of the Marxist Workers Tendency of the ANC,[3][4] a Trotskyist breakaway group of the ANC and precursor to the Democratic Socialist Movement.[16]

Achmat describes his political ideology as democratic socialist since the unbanning of the ANC in 1990.[15][4] Despite being a member of the ANC, he vigorously opposed the HIV/AIDS denialism promoted by former President Thabo Mbeki and other senior ANC members and in 2004 he withdrew his ANC membership under Mbeki's leadership.[17] In 2006, Achmat called on fellow party members to formulate appropriate HIV policies and oust Health Minister Manto Tshabalala-Msimang.[2][18][19][20] He has also been outspoken in his criticism of President Jacob Zuma and ANC corruption.[15][17][21]

Achmat stood as an independent for national parliament on the Western Cape regional list in the 2024 South African general election.[22] Achmat received 10679 votes, which does not reach the minimum threshold required to gain a seat in the National Assembly. He conceded defeat and vowed to continue politics by contesting in the 2026 local elections.[23]

LGBT rights activism

Achmat wrote a much-cited article about sexuality in South African prisons in 1993, based on his personal experiences with homosexual prison gangs, notably the 28s.[24]

Achmat co-founded the National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality in 1994, and as its director he ensured protections for gays and lesbians in the new South African Constitution, and facilitated the prosecution of cases that led to the decriminalisation of sodomy and granting of equal status to same-sex partners in the immigration process.[3][4][11][25][26]

HIV/AIDS activism

Summarize

Perspective

Achmat joined the AIDS Law Project based out of the University of the Witwatersrand in 1994, working as a paralegal under director Justice Edwin Cameron before replacing him as director that same year. He was involved in cases regarding the rights of HIV-diagnosed prisoners and hate crimes against gay and lesbian couples perpetrated by police.[26][27]

Achmat co-founded the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) in 1998,[18] a grassroots organization advocating for open and easy access to antiretroviral drugs for treating HIV. The AIDS Law Project and TAC work closely together in all the legal matters that arise in the course of advocating for the right to health, including prosecuting cases and defending TAC volunteers.[4]

Solidarity with people living with HIV and AIDS in South Africa

Achmat publicly announced his HIV-positive status in 1998 and stated that he was refusing to take antiretroviral drugs until all who needed them had access to them.[2][11][13] He began taking antiretrovirals in August 2003 when a national congress of TAC activists voted to urge him to begin antiretroviral treatment. He finally announced that he would start treatment shortly before the government announced that it would make antiretrovirals available in the public sector.[28] Achmat's motives have never been independently established and he does not mention this incident in affidavits that he has submitted on public interest matters containing his life history.[27]

Westville Prison incident

Achmat was one of 44 TAC activists arrested in 2006 for occupying provincial government offices in Cape Town as a protest in order to call for Health Minister Manto Tshabalala-Msimang and Correctional Services Minister Ngconde Balfour to be charged with culpable homicide for the death of an HIV-positive inmate at Westville Prison in Durban. The protesters were charged with trespassing and ordered to appear before court. The inmate was one of 15 prisoners who were plaintiffs in a case against the Departments of Health and Correctional Services, suing to be provided access to antiretroviral drugs. The court ordered the government to provide the drugs immediately.[18][29]

Social justice activism

In 2008, Achmat co-founded the Social Justice Coalition (SJC), an organisation with the aim of promoting the rights enshrined in South Africa's Constitution, particularly among poor and unemployed people living in the country. In 2009 he co-founded the Centre for Law and Social Justice, subsequently renamed Ndifuna Ukwazi (Dare to Know), with Gavin Silber.[1][30]

In 2013, Achmat and 18 other SJC activists were arrested for an illegal gathering outside the Cape Town Civic Centre, where they were protesting about sanitation services in the township of Khayelitsha.[31]

Allegations of sexual harassment cover up

Summarize

Perspective

In 2018, Achmat was accused of intimidating women against speaking about sexual harassment while he was the chair of the board of Equal Education, specifically regarding allegations against Doron Isaacs.[32] Achmat has denied the claims,[33] while also publicly defending Isaacs, stating that he does not believe Isaacs is a sexual predator. Achmat denied threatening complainants but admitted that he had "spoken firmly to people who have spread rumours or allegations of sexual or other misconduct without evidence as fact or faith".[34] Achmat has also boasted about being feared by people in South African civil society.[35] In the same radio interview Achmat claimed that he had heard rumours that his interviewer had stolen money and suggested that one of Isaacs' accusers was not credible because she had been gang-raped as a volunteer.[36]

Achmat joined calls for a public inquiry into Equal Education's handling of allegations of sexual misconduct in the organisation.[37] Equal Education[38] appointed retired judge Kathleen Satchwell to head an inquiry into the allegations. The Satchwell inquiry found that the allegations against Achmat and Isaacs were baseless.[39][40][41][42] Judge Satchwell likened the accusations to the "gutter journalism" of the Apartheid era in which "untested propaganda could rule the roost”.[43]

However, one member of Satchwell's three person inquiry, former United Nations' Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women Rashida Manjoo, dissented on the basis that she wished to take into considerations the anonymous allegations that were rejected by Satchwell. There was a total of 19 anonymous submissions through the Women's Legal Centre that were rejected by the commission.[44]

In 2020 Achmat became a director of Karoo Biosciences, which was a company established by Doron Isaacs.[45]

Personal life

Achmat was diagnosed HIV-positive in 1990.[2][4][46][10] In 2005 he had a heart attack, which his doctor said was unlikely to be caused by his HIV-positive status or treatment. He recovered sufficiently to return to his activism work.[47]

On 5 January 2008, Achmat married his partner and fellow activist Dalli Weyers at a ceremony in the Cape Town suburb of Lakeside. The ceremony was attended by then Mayor Helen Zille and presided over by his close friend Supreme Court of Appeal judge Edwin Cameron.[48][49] The couple divorced amicably in June 2011.[50]

Media

- Achmat's story is one of the 28 stories featured in the 2007 nonfiction book 28: Stories of AIDS in Africa by Stephanie Nolen.[51]

- Achmat is portrayed as a "Saint" in the 2009 video opera Fig Trees.[52]

- Achmat's critical role in the battle for mass antiretroviral treatment in Africa is portrayed in the award-winning 2013 documentary film Fire in the Blood.[53]

Filmography

Directing

Acting (as himself)

- Jonathan Dimbleby: The AIDS Crisis in Africa (2002) – presented by Jonathan Dimbleby

- Kommt Europa in die Hölle? (English: Is Europe Going to Hell?) – directed by Robert Cibis (2004)

- Darling! The Pieter-Dirk Uys Story (2007) – BFI award-winning documentary about Pieter-Dirk Uys directed by Julian Shaw

- Road to Ingwavuma (2008)

- Fig Trees (2009)

- Fire in the Blood (2013)

Recognition and awards

- 2001 – Desmond Tutu Leadership Award[57]

- 2001 – People in Need's Homo Homini Award for human rights activism[58]

- 2003 – National Press Club (South Africa) Newsmaker of the Year[59]

- 2003 – Jonathan Mann Award for Global Health and Human Rights[57]

- 2003 – Nelson Mandela Health and Human Rights Award[57]

- 2003 – Elected an Ashoka Fellow[60]

- 2003 – Named one of Time's 2003 European Heroes[57][61][62]

- 2004 – Voted 61st in SABC3's list of 100 Great South Africans[63]

- 2004 – Nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by the Quaker humanitarian group American Friends Service Committee[14][64]

- 2009 – Awarded Open Society Fellowship[65]

- 2011 – City of Cape Town Civic Honours[66][67]

- 2024 – CDC Foundation's Fries Prize for Improving Health[68]

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.