Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

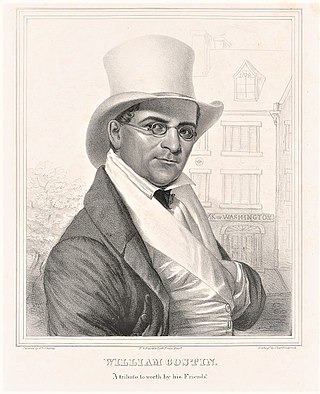

William Costin

African American activist and scholar (c. 1780–1842) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

William Costin (c. 1780 - May 31, 1842) was a free African-American activist and scholar who successfully challenged District of Columbia slave codes in the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia.[1][2]

Remove ads

Early life

Little is known of Costin's upbringing. His enslaved mother was Ann Dandridge-Costin, whose father is reputed to have been Col. John Dandridge of Williamsburg, Virginia,[3][4] making her the half-sister of Martha Washington.

Costin is believed to have been of African and Cherokee descent.[5] Native American slavery had ended and she should have been free under Virginia law via her maternal ancestry, but the slave colony put priority on African ancestry.[3] While Ann and several of her children lived at the Mount Vernon plantation, owned by George Washington on the Potomac River in Fairfax County, Virginia,[2] there is no evidence her son William lived there. He may have lived nearby with other family.

For more than a century, historians have identified Costin's probable father as John Parke Custis, George Washington's stepson.[6][7] Some debate Costin's legal status as "free" or "enslaved".[8] However, his mother was manumitted by Thomas Law, in 1802 shortly after the death of his mother-in-law, Martha Washington, and five years later Law emancipated Ann's children (including William) as well as his wife, Delphy Costin.[9]

Remove ads

Career

Summarize

Perspective

Around 1800, Costin was transferred from Mount Vernon to Washington City, what later became known as Washington, D.C.[citation needed] About that time, he married Philadelphia "Delphy" Judge, whom Martha Washington had given to her granddaughter Elizabeth Parke Custis Law as a wedding present in 1796. William, As well as Delphy and their children were manumitted in 1807 by Thomas Law, Elizabeth's husband. (see below).[citation needed]

In 1812, Costin built a house on A Street South on Capitol Hill. There he and his wife Delphy raised a large family.[10][11][12]

From 1818, Costin worked as a porter of the Bank of Washington.[2] He worked to save his money and buy properties in the developing capital. In 1818, Costin helped start a school for African-American children, which his daughter, Louisa Parke Costin (c. 1804 - October 31, 1831), eventually led. It was known as the first public school for black children in the city.[13]

In the August 1835 Snow Riot, when a white mob burned abolitionist institutions and those associated with free blacks, it spared the school.[14]

In addition to the school, Costin created other organizations. In 1821, he helped found the Israel Colored Methodist Episcopal Church, led by an African-American minister.[15] In June 1825, Costin co-founded an African-American masonic lodge known as Social Lodge #1 (originally #7).[16] In December 1825, he helped found the Columbian Harmony Society, providing burial benefits and a cemetery for use by African Americans. Working with nearly the same group with whom he started other organizations, including fellow hack driver William Wormley (c. 1800–1855) and educator George Bell (1761–1843), Costin served as the Society's vice president through 1826.[17]

Remove ads

Legal challenge

Summarize

Perspective

Challenge to Surety Bond Law

In 1821, Costin challenged part of the D.C. Code which restricted African Americans. The administration of Mayor Samuel Nicholas Smallwood had enacted that section to dissuade free blacks from settling there. The law required that free persons of color had:

to appear before the mayor with documents signed by three 'respectable' white inhabitants of their neighborhood vouching for their good character and means of subsistence. If the evidence was satisfactory to the mayor, the individuals were to post a yearly $20 bond with a 'good and respectable' white person as assurance of their 'good, sober and orderly conduct,' and to ensure that they would not become public charges or beggars in the streets. [T]o post an annual twenty dollar cash bond and present three references from white neighbors, purportedly to guarantee their peaceful behavior.[18]

Costin refused to comply, and was fined five dollars by a justice of the peace. He appealed his fine to the court.

In the case, Chief Judge William Cranch accepted that the City charter authorized it "to prescribe the terms and conditions upon which free Negroes and mulattoes may reside in the city."[1] (He was a nephew of the second U.S. President John Adams). Costin asked the court to strike the law entirely, saying that Congress could not delegate powers to the city that were unconstitutional, and that "the Constitution knows no distinction of color."[2][19]

Cranch defended the peace-bond law by pointing to certain barriers in the state voting and jury laws of the time, writing:

It is said that the [C]onstitution gives equal rights to all the citizens of the United States, in the several states. But that clause of the [C]onstitution does not prohibit any state from denying to some of its citizens some of the political rights enjoyed by others. In all the states certain qualifications are necessary to the right of suffrage; the right to serve on juries, and the right to hold certain offices; and in most of the states the absence of the African color is among those qualifications.[20]

But Cranch conceded that the law was unfair to free blacks who had long lived in the city and contributed to it, noting that they could not compel whites to give surety, and that the law threatened to force families apart. He ruled that those who had lived in the District prior to the law's enactment were exempted from having to abide by it.[1] He said, "It would seem to be unreasonable to suppose that Congress intended to give the [city] corporation the power to banish those free persons of color who had been guilty of no crime."[18]

Remove ads

Personal life

Summarize

Perspective

Marriage

In 1800, Costin married Philadelphia "Delphy" Judge (c. 1779 — December 13, 1831), the younger sister of Oney "Ona" Maria, known as Oney Judge (c. 1773— February 25, 1848), both of whom were daughters of Betty Davis (c. 1738–1795), and were so-called "dower" slaves of Martha Washington at Mount Vernon.[21][22][23][3]

According to Virginia estate law, the dower slaves passed to the Custis children upon Martha's death.[citation needed]

In 1807 and 1820, Costin purchased the freedom of seven relatives. In 1807, Thomas Law freed six of Costin's sisters and half-sisters for "ten cents."[24][25]

Law was the husband of Elizabeth ("Eliza") Parke Custis Law (August 21, 1776 – December 31, 1831), who inherited these slaves at the death of her grandmother, Martha Washington.[26]

In October 1820, the purchase of Costin's apparent cousin, Leanthe, who worked at the Mt. Vernon Mansion House, and was the daughter of Caroline,[27] involved two steps. First, George Washington Parke Custis sold her to Costin for an undisclosed sum. Twelve days later, Costin freed her for "five dollars."[28][29][30]

Costin remained in cordial contact with the Custis family throughout his life. In 1835, Eliza's brother, George Washington Parke Custis, supported Costin's side business driving a horse-and-buggy taxi.[31][32]

Funeral

Costin's funeral on June 4, 1842, was attended by U.S. Attorney Francis Scott Key, who had composed the song that became adopted as the national anthem.[33]

The funeral was notable for the long line of hansom cabs driven by Costin's friends.[34][35] The funeral procession included both white and black mourners, and a horseback processional.[36]

Remove ads

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads