Widener Library

Primary building of Harvard Library From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Library, housing some 3.5 million books,[2] is the centerpiece of the Harvard Library system. It honors 1907 Harvard College graduate and book collector Harry Elkins Widener, and was built by his mother Eleanor Elkins Widener soon after his death in the sinking of the Titanic in 1912.

| Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Library | |

|---|---|

"You could destroy all the other Harvard buildings and, with Widener left standing, still have a university." — G. L. Kittredge[1] | |

| |

| 42°22′24.4″N 71°06′59.4″W | |

| Location | Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Type | Academic |

| Established | 1915 |

| Branch of | Harvard Library |

| Collection | |

| Items collected | Primarily humanities and social sciences |

| Size |

|

| Access and use | |

| Access requirements | Harvard faculty, students & staff |

| Circulation | 600,000 items/year |

| Other information | |

| Website | Widener Library |

Widener's "vast and cavernous" [3] stacks hold works in more than one hundred languages which together comprise "one of the world's most comprehensive research collections in the humanities and social sciences." [4] Its 57 miles (92 km) of shelves, along five miles (8 km) of aisles on ten levels, comprise a "labyrinth" which one student "could not enter without feeling that she ought to carry a compass, a sandwich, and a whistle." [5]

At the building's heart are the Widener Memorial Rooms, displaying papers and mementos recalling the life and death of Harry Widener, as well as the Harry Elkins Widener Collection,[6] "the precious group of rare and wonderfully interesting books brought together by Mr. Widener",[7] to which was later added one of the few perfect Gutenberg Bibles—the object of a 1969 burglary attempt conjectured by Harvard's police chief to have been inspired by the 1964 heist film Topkapi.

Background, conception and gift

Summarize

Perspective

Predecessor

By the opening of the twentieth century alarms had been issuing for many years about Harvard's "disgracefully inadequate" [8]: 276 library, Gore Hall, completed in 1841 (when Harvard owned some 44,000 books)[9]: 5 and declared full in 1863.[9]: 5 Harvard Librarian Justin Winsor concluded his 1892 Annual Report by pleading, "I have in earlier reports exhausted the language of warning and anxiety, in representing the totally inadequate accommodations for books and readers which Gore Hall affords. Each twelve months brings us nearer to a chaotic condition";[10]: 15 his successor Archibald Cary Coolidge asserted that the Boston Public Library was a better place to write an undergraduate thesis.[11]: 29 Despite substantial additions in 1876 and 1907,[12] in 1910 a committee of architects termed Gore Hall

unsafe [and] unsuitable for its object ... No amount of tinkering can make it really good ... Hopelessly overcrowded ... leaks when there is a heavy rain ... intolerably hot in summer ... Books are put in double rows and are not infrequently left lying on top of one another, or actually on the floor ...[13]: 51–52

With university librarian William Coolidge Lane reporting that the building's light switches were delivering electric shocks to his staff,[14] and dormitory basements pressed into service as overflow storage[15] for Harvard's 543,000 books,[16]: 50 the committee drew up a proposal for replacement of Gore in stages. Andrew Carnegie was approached for financing without success.[note 1]

Death of Harry Widener

On April 15, 1912, Harry Elkins Widener—scion of two of the wealthiest families in America,[20] a 1907 graduate of Harvard College, and an accomplished bibliophile despite his youth[21]—died in the sinking of the Titanic. His father George Dunton Widener also perished, but his mother Eleanor Elkins Widener survived.[20]

Harry Widener's will instructed that his mother, when "in her judgment Harvard University shall make arrangements for properly caring for my collection of books ... shall give them to said University to be known as the Harry Elkins Widener Collection",[note 2] and he had told a friend, not long before he died, "I want to be remembered in connection with a great library, [but] I do not see how it is going to be brought about." [21]

To enable the fulfillment of her son's wishes Eleanor Widener briefly considered funding an addition to Gore Hall, but soon determined to build instead a completely new and far larger library building—"a perpetual memorial" [17]: 90 to Harry Widener, housing not only his personal book collection but Harvard's general library as well,[25] with room for growth.[26] As Biel has written, "The [Harvard architects] committee's Beaux Arts design [for Gore Hall's projected replacement], with its massiveness and symmetry, offered monumentality with nothing more particular to monumentalize than the aspirations of the modern university"—until the Titanic sank and "through delicate negotiation, [Harvard] convinced Eleanor Widener that the most eloquent tribute to Harry would be an entire library rather than a rare book wing." [17]: 88-89

Terms and cost of gift

To her gift Eleanor Widener attached a number of stipulations,[B]: 43 including that the project's architects be the firm of Horace Trumbauer & Associates,[27] which had built several mansions for both the Elkins and the Widener families.[B]: 27 "Mrs. Widener does not give the University the money to build a new library, but has offered to build a library satisfactory in external appearance to herself," Harvard President Abbott Lawrence Lowell wrote privately. "The exterior was her own choice, and she has decided architectural opinions." [28]: 167 Harvard historian William Bentinck-Smith has written that

To [Harvard officials] Mrs. Widener was a lovely and generous lady whose wealth, power, and remoteness made her a somewhat terrifying figure who must not be roused to annoyance or outrage. Once [construction] began, all financial transactions were the donor's private business, and no one at Harvard ever knew the exact cost. Mrs. Widener was counting on $2 million, [but] it is probable the cost exceeded $3.5 million [equivalent to $80 million in 2023].[note 3]

Though Harvard awarded Trumbauer an honorary degree on the day of the new library's dedication,[note 4] it was Trumbauer associate Julian F. Abele who had overall responsibility for the building's design,[27] which largely followed the 1910 architects' committee's outline (though with the committee's central circulation room shifted from the center to the northeast corner, yielding pride of place to the Memorial Rooms).[note 5]

After Gore Hall was demolished to make way, ground was broken on February 12, 1913, and the cornerstone laid June 16. By later that year some 50,000 bricks were being laid each day.[19]

Building

Summarize

Perspective

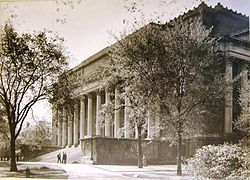

At Harvard's "geographical and intellectual heart" [34] directly across Tercentenary Theatre from Memorial Church,[35] Widener Library is a hollow rectangle of "Harvard brick with Indiana limestone traceries",[36] 250 by 200 by 80 feet high (76 by 61 by 24 m)[28]: 167 and enclosing 320,000 square feet (30,000 m2)[34], "colonnaded on its front by immense pillars with elaborate [Corinthian capitals],[37]: 362 all of which stand at the head of a flight of stairs that would not disgrace the capitol in Washington." [28] Sources describe the building's style as (variously) Beaux-Arts,[17]: 88 Georgian,[38]: 57 [39]: 457 Hellenistic,[40]: 281 or "the austere, formalistic Imperial [or 'Imperial and Classical'] style displayed in the Law School's Langdell Hall and the Medical School Quadrangle".[37]: 361

The east, south, and west wings house the stacks, while the north contains administrative offices and various reading rooms, including the Main Reading Room (now the Loker Reading Room)—which, spanning the entire front of the building and some 42 feet (13 m) in both depth and height, was termed by architectural historian Bainbridge Bunting "the most ostentatious interior space at Harvard." [41]: 154 A topmost floor, supported by the stacks framework itself, contains thirty-two rooms for special collections, studies, offices, and seminars.[42]: 327-8

The Memorial Rooms (see § Widener Memorial Rooms) are in the building's center, between what were originally two light courts (28 by 110 ft or 8.5 by 33 m)[43] now enclosed as additional reading rooms.[44]

Dedication

The building was dedicated immediately after Commencement Day exercises on June 24, 1915. Lowell and Coolidge mounted the steps to the main door, where Eleanor Widener presented them with the building's keys.[46] The first book formally brought into the new library was the 1634 edition of John Downame's The Christian Warfare Against the Devil, World, and Flesh,[9]: 18 believed (at the time) to be the only volume, of those bequeathed to the school by John Harvard in 1638, to have survived the 1764 burning of Harvard Hall.[47]

"President Lowell accepting the key from Mrs. Widener"

"Even from the very entrance one [can glimpse] the portrait of young Harry Widener" far inside.

Flanking the Memorial Rooms' entrance, murals by John Singer Sargent honor World War I dead.

In the Memorial Rooms, after a benediction by Bishop William Lawrence,[53] a portrait of Harry Widener was unveiled, then remarks delivered by Senator Henry Cabot Lodge (speaking on "The Meaning of a Great Library" [54] on behalf of Eleanor Widener) and Lowell ("For years we have longed for a library that would serve our purpose, but we never hoped to see such a library as this").[46] Afterward (said the Boston Evening Transcript ) "the doors were thrown open, and both graduates and undergraduates had an opportunity to see the beauties and utilities of this important university acquisition." [53]

"I hope it will become the heart of the University," Eleanor Widener said, "a centre for all the interests that make Harvard a great university." [55]

Widener Memorial Rooms

The central Memorial Rooms—an outer rotunda[56] housing memorabilia of the life and death of Harry Widener,[57] and an inner library displaying the 3300 rare books collected by him—were described by the Boston Sunday Herald soon after the dedication:

The [rotunda] is of Alabama marble except the domed ceiling, with fluted columns and Ionic capitals [while the library] is finished in carved English oak, the carving having been done in England; the high bookcases are fitted with glass shelves and bronze sashes, the windows are hung with heavy curtains [and] upon the desks are vases filled with flowers.

The big marble fireplace and the portrait of Harry Widener occupy a large portion of the south wall. Standing front of the fireplace one may look through the vista made by the doorways, the staircases within and the stairs without and get a glimpse of the green campus.[note 7]

Conversely, "even from the very entrance [of the building] one will catch a glimpse in the distance of the portrait of young Harry Widener on the further wall [of the Memorial Rooms], if the intervening doors happen to be open." [42]: 325

For many years Eleanor Widener hosted Commencement Day luncheons in the Memorial Rooms.[9]: 20 The family underwrites their upkeep,[59] including weekly renewal of the flowers[60]—originally roses but now carnations.[note 8]

Amenities and deficiencies

Touted as "the last word in library construction",[62] the new building's amenities included telephones, pneumatic tubes, book lifts and conveyors, elevators,[7] and a dining-room and kitchenette "for the ladies of the staff".[63]: 676 Advertisements for the manufacturer of the building's shelving highlighted its "dark brown enamel finish, harmonizing with oak trim",[64] and special interchangeable regular and oversize shelves meant that books on a given subject could be shelved together regardless of size.[note 9]

The Library Journal found "especially interesting not so much the spacious and lofty reading rooms" [33] as the innovation[67]: 255 of placing student carrels and private faculty studies directly in the stack, reflecting Lowell's desire to put "the massive resources of the stack close to the scholar's hand, reuniting books and readers in an intimacy that nineteenth-century ['closed-stack' library designs] had long precluded".[B]: 45–46 (Competition for the seventy[42]: 327 coveted faculty studies has been a longstanding administrative headache.)[note 10]

Nonetheless, certain deficiencies were soon noted.[B]: 107 A primitive form of air conditioning was abandoned within a few months.[67][68]: 97 "The need of better toilet facilities [in the stacks] has been pressed upon us during the past year by several rather distressing experiences," Widener Superintendent Frank Carney wrote discreetly in 1918.[note 11] And after a university-wide search for castoff furniture left many of the stacks' 300 carrels still unequipped,[69] Coolidge wrote to J. P. Morgan Jr., "There is something rather humiliating in having to proclaim to the world that [Widener offers] unequalled opportunity to the scholar and investigator who wishes to come here, but that in order to use these opportunities he must bring his own chair, table and electric lamp." (A week later Coolidge wrote again: "Your very generous gift [has helped] pull me out of a most desperate situation.")[note 12]

Later-built tunnels, from the stacks level furthest underground, connect to nearby Pusey Library, Lamont Library,[71] and Houghton Library.[72] An enclosed bridge connecting to Houghton's reading room via a Widener window—built after Eleanor Widener's heirs agreed to waive[68]: 75 her gift's proscription of exterior additions or alterations[13]: 79 —was removed in 2004.[73] Houghton and Lamont were built in the 1940s to relieve Widener,[74] which had become simultaneously too small—its shelves were full[75]—and too large—its immense size and complex catalog made books difficult to locate.[note 13] But with Harvard's collections doubling every 17 years, by 1965 Widener was again close to full,[76] prompting construction of Pusey,[77] and in the early 1980s library officials "pushed the panic button"[78] again, leading to the construction of the Harvard Depository in 1986.[79]

Collections and stacks

Summarize

Perspective

The ninety-unit Harvard Library system,[37]: 361 of which Widener is the anchor, is the only academic library among the world's five "megalibraries"—Widener, the New York Public Library, the Library of Congress, France's Bibliothèque Nationale, and the British Library[81]: 352 —making it "unambiguously the greatest university library in the world," in the words of a Harvard official.[82]

According to the Harvard Library's own description, Widener's humanities and social sciences collections include

holdings in the history, literature, public affairs, and cultures of five continents. Of particular note are the collections of Africana, Americana, European local history, Judaica, Latin American studies, Middle Eastern studies, Slavic studies, and rich collections of materials for the study of Asia, the United Kingdom and Commonwealth, France, Germany, Italy, Scandinavia, and Greek and Latin antiquity. These collections include significant holdings in linguistics, ancient and modern languages, folklore, economics, history of science and technology, philosophy, psychology, and sociology.[note 14]

The building's 3.5 million volumes[34] occupy 57 miles (92 km) of shelves[83]: 4 along five miles (8 km) of aisles[84] on ten levels divided into three wings each.[83]: 4

Alone among the "megalibraries", only Harvard allows patrons the "long-treasured privilege" of entering the general-collections stacks to browse as they please, instead of requesting books through library staff.[note 15] Until a recent renovation the stacks had little signage—"There was the expectation that if you were good enough to qualify to get into the stacks you certainly didn't need any help" (as one official put it)[44] so that "learning to [find books in] Widener was like a rite of passage, a test of manhood",[89] and a 1979 monograph on library design complained, "After one goes through the main doors of Harvard's Widener Library, the only visible sign says merely ENTER." [90] At times color-coded lines and shoeprints have been applied to the floors to help patrons keep their bearings.[91][92]

As of 2015 some 1700 persons enter the building each day, and about 2800 books are checked out.[93] Another 3 million Widener items reside offsite[94] (along with many millions of items from other Harvard libraries) at the Harvard Depository in Southborough, Massachusetts, from which they are retrieved overnight on request.[B]: 170-1 A project to insert barcodes into each book, begun in the late 1970s, had some 1 million volumes yet to reach as of 2006.[94]

Harry Elkins Widener Collection

The works displayed in the Memorial Rooms comprise Harry Widener's collection at the time of his death, "major monuments of English letters, many remarkable for their bindings and illustrations or unusual provenance":[9]: 9 Shakespeare First Folios;[37]: 362 a copy of Poems written by Wil. Shake-speare, gent. (1640) in its original sheepskin binding;[95] an inscribed copy of Boswell's Life of Samuel Johnson; Johnson's own Bible ("used so much by its owner that several pages were worn out and Johnson copied them over in his own writing");[59] and first editions, presentation copies, and similarly valuable volumes of Robert Louis Stevenson, Thackeray, Charlotte Brontë, Blake, George Cruikshank, Isaac Cruikshank, Robert Cruikshank[6] and Dickens—including the petty cash book kept by Dickens while a young law clerk.[96] Book collector George Sidney Hellman, writing soon after Harry Widener's death, observed that he was "not satisfied alone in having a rare book or a rare book inscribed by the author; it was with him a prerequisite that the volume should be in immaculate condition." [96]

Harry Widener "died suddenly, just as he was beginning to be one of the world's great collectors," [55] said the Collection's first curator.[52]: 6 "They formed a young man's library, and are to be preserved as he left it" [55]—except that the Widener family has the exclusive privilege of adding to it.[note 16] Harvard's "greatest typographical treasure" [97]: 17 is one of the only thirty-eight perfect copies extant[98] of the Gutenberg Bible,[99] purchased while Harry was abroad by his grandfather Peter A. B. Widener (who had intended to surprise Harry with it once the Titanic docked in New York)[59] and added to the Collection by the Widener family in 1944.[note 17]

Like all Harvard's valuable books, works in the Widener Collection may be consulted by researchers demonstrating a genuine research need.[103]

Parallel classification systems and dual catalogs

Like many large libraries, Widener originally classified its holdings according to its own idiosyncratic system—the "Widener" (or "Harvard") system—which (writes Battles) follows "the division of knowledge in its [early twentieth-century] formulation. The Aus class contains books on the Austro-Hungarian Empire; the Ott class serves the purpose for the Ottoman Empire. Dante, Molière, and Montaigne each gets a class of his own." [83]: 15

In the 1970s new arrivals began to be classified according to a modified version of the Library of Congress system.[105]: 256 [B]: 159 The two systems' differences reflect "competing theories of knowledge ... In a sense, the [old] Widener system was Aristotelian; its divisions were empirical, describing and reflecting the languages and cultural origins of books and highlighting their relations to one another in language, place, and time; [the Library of Congress system], by contrast, was Platonic, looking past the surface of language and nation to reflect the idealized, essential discipline in which each [item] might be said to belong." [B]: 158-9

Because of the impracticality of reclassifying millions of books, those received before the changeover remain under their original "Widener" classifications. Thus among works on a given subject, older books will be found at one shelf location (under a "Widener" classification) and newer ones at another (under a related Library of Congress classification).[106][92]

In addition, an accident of the building's layout led to the development of two separate card catalogs—the "Union" catalog and the "Public" catalog—housed on different floors and having a complex interrelationship "which perplexed students and faculty alike." It was not until the 1990s that the electronic Harvard On-Line Library Information System was able to completely supplant both physical catalogs.[B]: 137,192

Departmental and special libraries

The building also houses a number of special libraries in dedicated spaces outside the stacks, including:

- The Fred N. Robinson Celtic Seminar Library

- The Hamilton A.R. Gibb Islamic Seminar Library

- The Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature

- The Herbert Weir Smyth Classical Library

- The Francis James Child Memorial Library (English Department)

- The James A. Notopoulos Collection of Modern Greek Ballads and Songs

There are also special collections in the history of science, linguistics, Near Eastern languages and civilizations, paleography, and Sanskrit.[107]

The contents of the Treasure Room, holding Harvard's most precious rare books and manuscripts (other than the Harry Elkins Widener Collection itself) were transferred to newly built Houghton Library in 1942.[97]: 15

In literature and legend

Summarize

Perspective

Swim-requirement, ice-cream, and other legends

Legend holds that to spare future Harvard men her son's fate, Eleanor Widener insisted, as a condition of her gift, that learning to swim be made a requirement for graduation from Harvard.[108][109] (This requirement, the Harvard Crimson once elaborated erroneously, was "dropped in the late 1970s because it was deemed discriminatory against physically disabled students".)[61] "Among the many myths relating to Harry Elkins Widener, this is the most prevalent", says Harvard's "Ask a Librarian" service. Though Harvard has had swimming requirements at various times (e.g. for rowers on the Charles River, or as a now-defunct test for entering freshmen)[110] Bentinck-Smith writes that "There is absolutely no evidence ... that [Eleanor Widener] was, as a result of the Titanic disaster, in any way responsible for [any] compulsory swimming test." [note 18]

Another story, holding that Eleanor Widener donated a further sum to underwrite perpetual availability of ice cream (purportedly Harry Widener's favorite dessert) in Harvard dining halls, is also without foundation.[108] A Widener curator's compilation of "fanciful oral history" recited by student tour guides includes "Flowers mysteriously appear every morning outside the Widener Room" and "Harry used to have carnations dyed crimson to remind him of Harvard, and so his mother kept up the tradition" in the flowers displayed in the Memorial Rooms.[112]

Literary references

In H. P. Lovecraft's fictional universe Cthulhu Mythos, Widener is one of five libraries holding a 17th-century edition of the Necronomicon, hidden somewhere in the stacks.[113]

Thomas Wolfe, who earned a Harvard master's degree in 1922,[114] told Max Perkins that he spent most of his Harvard years in Widener's reading room.[28] He wrote of "[wandering] through the stacks of that great library like some damned soul, never at rest—ever leaping ahead from the pages I read to thoughts of those I want to read";[115] his alter ego Eugene Gant read with a watch in his hand, "laying waste of the shelves." [116]

Historian Barbara Tuchman considered "the single most formative experience" of her career the writing of her undergraduate thesis, for which she was "allowed to have as my own one of those little cubicles with a table under a window" in the Widener stacks, which were "my Archimedes' bathtub, my burning bush, my dish of mold where I found my personal penicillin." [5]

Burglary and other incidents

Summarize

Perspective

Over the years, Widener has been the scene of various criminal exploits "infamous for their fecklessness and ignominity." [B]: 59

Joel C. Williams

In 1931 former graduate student Joel C. Williams was arrested after attempting to sell two Harvard library books to a local book dealer. Charles Apted and other Harvard officials visited Williams' home[119] where (posing as "book buyers" to spare the feelings of Williams' family)[B]: 88 they found thousands[119] of books which Williams had stolen over the years,[86]: D many badly damaged. The "absolutely crazy" Williams would "go to students studying in Widener and ask them what course they were taking. He would then borrow all the books for that course in the library. Then no one could get any to study", library official John E. Shea later recalled.[note 19]

Despite the misleading[121] implication of bookplates placed in the 2504[86]: D recovered books, Harvard's charges against Williams were dropped after he was indicted on book-theft charges in another jurisdiction, which imposed a sentence of hard labor.[122] After the unrelated arrest of a book-theft ring operating at Harvard, there was a "noticeable increase in the number of missing books secretly returned to the library", the Transcript reported in 1932.[B]: 89

Gutenberg Bible theft

On the night of August 19, 1969 an attempt was made to steal the library's Gutenberg Bible, valued at $1 million[123] (equivalent to $6 million in 2023).[29] Equipped with a hammer, pry bar, and other burglarious implements, the 20-year-old would-be thief[123] hid in a lavatory until after closing, then made his way to the roof, from which he descended via a knotted rope to break through a Memorial Room window. But after smashing the bible's display case and placing its two volumes in a knapsack, he found the additional 70 pounds (32 kg) made it impossible for him to reclimb the rope.[86]: D

Eventually he fell some 50 feet (15 m)[97]: 45 to the pavement of one of the light courts, where he lay semiconscious[124] until his moans were heard by a janitor;[97]: 45 he was found about 1 a.m.[125] with injuries including a fractured skull.[124] "It looks like a professional job all right, in the fact that he came down the rope," commented Harvard Police Chief Robert Tonis. "But it doesn't look very professional that he fell off." [123] Tonis speculated that the attempt may have been modeled on a similar caper depicted in the 1964 film Topkapi,[125] though a retired Harvard librarian later commented that the thief (who was later judged insane)[126] "evidently knew nothing about books—or, at least, about selling them ... There was no explanation of what he expected to do with the Bible." [68]: 72

Only the books' bindings (which were "not valuable [and] did just what a good binding is supposed to do: they protected the inside contents")[123] were damaged.[124] Since the incident only one or the other Bible volume is on display at any given time[86]: E and a replica has been substituted at times of heightened security concern.[note 20]

1969 Vietnam War protests

In the spring of 1969, during Harvard student demonstrations against the war in Vietnam, rumors spread of a possible attack on Widener.[128][129] Following the occupation of University Hall by protesters, and their subsequent violent ejection by police, volunteer librarians and faculty stood watch inside Widener for several nights.[130]

"The Slasher"

Around 1990, empty bindings stripped of their pages began to appear in the Widener stacks. Eventually some 600 mutilated books were discovered, the vandal particularly targeting works on early Christianity in Greek, Latin, or unusual languages such as Icelandic.[85] Notes left at Widener, and later at Northeastern University, threatened graphically described mutilations of library workers, cyanide gas attacks,[131] and bombings of libraries and a local bank.[132] Other notes instructed that $500,000 be left in a Northeastern library, demanded that Northeastern "terminate all Jew personnel", and directed that $1 million be left in the Widener stacks: "pUt THe mONEy FucKer BEhiNd THE eLevATOR on D WEST in THE basemENT WhERE tHe 1,000,000.00 dollaRS IN rare GreEK bOOks wAS slASHEd ApARt MIGNE GREEK PATROLOGIA." These "ransom drops" were staked out by the FBI,[note 21] and surveillance cameras installed in ersatz books, without result.[134]

In 1994 police connected an incident at Northeastern, in which a library worker there (a former Widener employee) was caught stealing chemistry books, with the fact that chemistry texts had been among the works mutilated at Widener.[85][dead link] Officials found "a kind of renegade reference room" in the worker's basement,[135] including library books, piles of ripped-out pages, a microfilm camera, and hundreds of unusable microfilms he had haphazardly made of the books (worth $180,000) he had destroyed.[85] At trial "The Slasher" said he had acted in revenge for the eighteen months he had been detained in a state psychiatric hospital after expiration of a six-month jail term he had received for a minor offense.[131]

Artwork

Summarize

Perspective

Two of Gore Hall's granite pinnacles were preserved, and flank Widener's rear entrance.[28]: 151

In the 1920s the university commissioned John Singer Sargent to paint, within the fourteen-foot-high arched panels flanking the entrance to the Memorial Rooms, two murals giving tribute to Harvard's World War I dead: Death and Victory and Entering the War.[note 22] The accompanying inscription, by Lowell, reads: "Happy those who with a glowing faith / In one embrace clasped Death and Victory".[137] With Memorial Church, which directly faces Widener, these constitute what the Boston Public Library calls "the most elaborate World War I memorial in the Boston area." [35]

Above the Memorial Rooms entrance is inscribed:

To the memory of Eleanor Elkins Rice • whose noble and endearing spirit inspired the conception and completion of this Memorial Library • 1938.[138]

(Eleanor Elkins Widener became Eleanor Elkins Rice when, in October 1915, she married Harvard professor[139] and surgeon[140] Alexander Hamilton Rice Jr., a noted South American explorer whom she had met at the library's dedication four months earlier.[56] She died in 1937.)[20]

On the second floor is a bronze bust by Albin Polasek of sculptor and muralist Frank Millet, who had also died on the Titanic.[142] In the main reading room is a sculpture of George Washington; on the stairs to the third floor a sculpture of John Elbridge Hudson; and on the ground floor a sculpture of Henry Ware Wales,[143] as well as vaulted hallways—"just like the Oyster Bar at Grand Central ... astounding", according to historian Thomas Gick—by Rafael Guastavino, who (with his son) also designed and built domes and vaults in buildings such as Carnegie Hall, the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, and the Boston Public Library.[112]

Three dioramas—depicting the grounds, buildings, and vicinity of Harvard Yard in 1667, 1775 and 1936—were installed behind the main stairs in 1947, but removed during renovations in 2004.[144] A six-foot-square bronze tablet, featuring a bas relief of Gore Hall, is at the exterior northwest corner. Its inscription reads in part:

On this spot stood Gore Hall • Architect Richard Bond, Supervisor • Daniel Treadwell • Built in the Year 1838 • In honor of Christopher Gore Class of 1776. • Fellow of the College, Overseer, Benefactor • Governor of the Commonwealth. • Senator of the United States. • The first use of modern book-stacks was in this library. ... [145]

Restrictions on women

Summarize

Perspective

The building originally included a separate Radcliffe Reading Room behind the card catalogs—"barely large enough for a single table"—to which female students were restricted "for fear their presence would distract the studious Harvard men" in the main reading room.

In 1923 a sequence of communications between Librarian William Coolidge Lane and another Harvard official dealt with "the incident of Miss Alexander's intrusion into the reading room",[B]: 37,86 and Keyes Metcalf, Director of University Libraries from 1937 to 1955, wrote that early in his tenure a Classics professor "rushed into my office, looking as if he were about to have an apoplectic stroke, and gasped, 'I've just been in the reading room, and there is a Radcliffe girl in there!'" By then female graduate students were permitted to enter the stacks, but only until 5 p.m., "after which time it was thought they would not be safe there". [note 23]

"Even the ever-present problem of inadequate lavatories worked to deny functional access to women", wrote Battles. "Patrons requesting directions to a women's restroom were routinely misled, denied access, or simply told that such things did not exist at a college for men such as Harvard." [B]: 115

By World War II (Elizabeth Colson recalled years later) "we could go into the [Main Reading Room] and use the encyclopedias and things like that there, if we stood up, but we couldn't sit down",[146]: 56–57 and only by special permission (which even female faculty members had to request in writing) could a woman work in the building in the evening.[B]: 112-4

Renovation

Summarize

Perspective

A five-year, $97 million renovation completed in 2004[44] (the first since the building opened)[148] added fire suppression and environmental control systems, upgraded wiring and communications, remodeled various public spaces, and enclosed the light courts to create additional reading rooms[44] (beneath which several levels of new offices and mechanical equipment were hidden).[149]

"Claustrophobia-inducing" elevators were replaced,[92] the bottom shelves on the lowest stacks level were removed in recognition of chronic seepage problems,[148] Widener's "olfactory nostalgia ... actually the smell of decaying books" was addressed,[150] and unrestricted light and air—seen as desirable when Widener was built but now considered "public enemies one and two for the long-term safety of old books"—were brought under control.[note 25]

Some changes required that the Widener family grant relief[151] from the terms of Eleanor Widener's gift, which forbade that "structures of any kind [be] erected in the courts around which the [Library] is constructed, but that the same shall be kept open for light and air".[13]: 79 [B]: 42

The need to relocate each of the building's 3.5 million volumes twice—first to temporary locations, then to new permanent locations, as work proceeded aisle by aisle—was turned to advantage, so that by the end of the renovation related materials in the library's two classification systems (see § Parallel classification systems) were physically adjacent for the first time;[106][92] the chart showing the floor and wing location, within the stacks, of each subject classification was revised sixty-five times during construction.[44]

The project received the 2005 Library Building Award from the American Library Association and the American Institute of Architects.[152]

Notes

- [17]: 88 "When I cease to be President of Harvard College," Lowell wrote around this time, "I shall join one of the mendicant orders, so as to have less begging to do ..." [B]: 23 In May 1911 the Boston American (published by disgraced Harvard dropout William Randolph Hearst) [18] carried a mock advertisement: "Wanted—a millionaire. Will some kind millionaire please give Harvard University a library building? Tainted money not barred. Mr. Rockefeller, take notice. Mr. Carnegie, please write." [17]: 87

- [22] Stipulations on conditions of storage began to appear in bequests to Harvard's libraries during the nineteenth century.[23] For example, the 1883–84 annual report of Harvard Divinity School's dean noted that Ezra Abbot's widow, in donating four thousand volumes from his personal library, asked for assurance that a better and safer replacement for the existing Divinity School library building be constructed promptly; the dean also wrote that such a replacement would encourage future donors.[24]

- [9]: 14 [29] Eleanor Widener expressed vexation at newspapers' misreporting of the circumstances of her gift, writing to Lowell, "I want emphasized ... that the library is a memorial to my dear son, to be known as the 'Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Library,' given by me & not his [paternal grandfather P. A. B. Widener] as has been so often stated." [30] Years later her second husband A. H. Rice Jr. insisted that Lowell do his best "to see that in all official reports, etc. the Library is referred to as the Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Library—Widener! Not one cent of Widener money, one second of Widener thought, nor one ounce of Widener energy were expended on either the conception or construction of the Library. [9]: 15

- [31]: 147 Eleanor Widener was not similarly honored, because women were ineligible for Harvard honorary degrees at the time.[16]: 72 The Harvard Graduates Magazine reassured its readers that the admission of ladies, for the first time, to certain Commencement proceedings "will not, however, create any precedent. It was due to the dedication of the Library, which demanded that once, at least, custom should be broken in favor of Mrs. Widener and her friends ..." [32]

- [17]: 89 The Library Journal commented: "The building has administrative disadvantages necessitate by its character as a memorial, with a central fane housing the private library collected by young Widener ... This occupies what would otherwise be the central court and cuts off access from the stack except at the two ends, but is scarcely to be criticized in view of the splendor of the gift and the parental affection thus enshrined and perpetuated by Mrs. Widener." [33]

- [49] The rug is a Heriz Persian;[50] on the desk is an unsigned Tiffany lamp.[51] In the library's early years, when the Memorial Rooms served as the office of the Widener Collection's curator, fires were sometimes set in the fireplace.[52]

- [58] Trumbauer "had no rivals when it came to tempting clients to spend immodest sums", wrote Wayne Andrews,[9]: 16 and Biel wrote that he had "made his name and fortune by knowing that 'only a magnificent setting could hope to satisfy an American with a magnificent income,' and he had already imparted such magnificence to the Widener and Elkins mansions and an assortment of other palaces ... [He] knew who his client was, so he gave elaborate attention to memorializing Harry in style" in the Memorial Rooms.[17]: 89

- [61] From the start it was Eleanor Widener's particular instruction that there always be flowers in the Memorial Room,[58] and in March 1916 she reminded George Parker Winship, curator of the Widener Collection (who at the time used the Memorial Room as his office): "Will you please see that at all times fresh flowers are kept on your table by the photograph of my dear son Harry, the same to be paid out of funds set aside for the maintenance of the Memorial Room. This is the only request I make, and I beg of you to see that it is always carried out." [B]: 43

- [7] In the basement (later converted to additional shelving as stacks levels C and D after a further donation by Eleanor Widener in 1928) [65] were

- the dynamos which run the five elevators and two book-lifts, the compressed air machinery for the pneumatic tubes, the dynamo and fan for the vacuum-cleaning system, a pump connected with the steam-heating apparatus, enormous fans which pump warm air into the Reading-Room and the stack, a filter through which passes all water which enters the building, and the connections for electric light and power. The building is to be heated by steam, conveyed through a tunnel from the plant of the Elevated Railroad Company, which also furnishes heat to the other buildings of the College Yard and to the freshman dormitories.[63]: 328

- "The [faculty studies] are not all fully used," Coolidge wrote in 1917, "but you will understand that I can not go to a professor and tell him that I think he is not making use of his space and had better give it up. I have tried in some cases hinting to people that if they did not need their quarters there were others who could make good use of them. These hints have usually met with conspicuously little success." [B]: 72-75

- "At present", Carney continued, "everyone using the stack is obliged to go to the basement to reach the public toilet. This in the case of a man using one of the top floors of the stack is a particularly long trip ... An emergency toilet ... would be a desirable thing." [B]: 59 By 1937 security changes had made the situation even worse, so that someone on the lowest stack level had to climb seven flights of stairs, exit the stack, then descend another set of stairs to reach the basement toilet. Eventually toilets were installed in the stack by Harvard Librarian Keyes Metcalf, who later wrote that "As far as graduate students are concerned, I will go down in history as the man who provided toilet facilities in the Widener stack." [68]: 139–40

- [13]: 102 Even during construction Harvard officials worried about financing the new library's furnishings and equipment, which Eleanor Widener did not undertake to supply except in the case of the building's "great public rooms [which she] handsomely furnished".[69] In early 1914, for example, a series of letters between Lane and Snead & Co. (the builders of the stacks) discussed the design of signs which would direct patrons to the various subject classifications; but in June, Lane apologized for being unable to finalize a planned order for these signs:

- Our situation in regard to this is an embarrassing one ... The College has no means in hand to cover this expense, and we do not see where we are going to get what is needed for this and other similar purposes. We do not feel ourselves in a position to ask Mrs. Widener or Mr. Trumbauer to provide these necessary fittings, indispensable as they are for the proper use of the shelves. The labels for the ends of the stack and the number plates we can of course do without by fastening up cardboard signs ...

- [68]: 27 On any given floor of the stack, it is 400 feet (120 m) from the entrance stairwell to the furthest shelves, and a patron "concerned with material in widely different fields may find that a tiresome amount of walking and stair climbing is involved." [67]: 91,74 English professor Howard Mumford Jones complained in 1950 that in preparing a lecture on Robert Frost, after a long hunt for a bibliography listing works he would need to consult, then locating those works in the complicated catalogs, he found that

- the American Scholar is shelved on Floor A; the New English Quarterly under New England; the Classical Journal is shelved on Floor 5; and College English is in Educ on Floor B. I shall not go into the matter of distribution [of these works among wings] East, South, and West ...[B]: 133–34

- [85][86]: E It was not always so. Originally "school-boys" earning forty dollars per month (equivalent to $630 in 2024)[87] fetched books requested by patrons via slips. "Should a slip be received for a book in a part of the stack where a boy has just been sent—particularly in the West stack, which is the farthest away from the central station—the [request] is telephoned across on the internal telephone." [B]: 56 But by about 1930 Widener's stacks "were almost wide open to anyone who wanted to enter", so much so that in a single day a group of thieves was able to steal some one hundred valuable works on American history.[88]

- [59] The December 31, 1912 agreement between Eleanor Widener and the President and Fellows of Harvard College provides that "this collection, together with such books as may be added to it by members of the family of the Donor, shall at all times be kept separate and apart from the general library of Harvard ... Harvard is not ... ever to add anything to the said Harry Elkins Widener collection ... [S]aid books shall not be taken or removed from the two rooms specially set apart ... excepting only when necessary for the repair or restoration of any volume ..." [13]: 78–79

- [100] Harry Widener knew his grandfather had bought the Gutenberg Bible, but not that it was intended for him. "I wish it was for me but it is not", he wrote to a friend.[101] After Harry's death, and (soon after) that of his grandfather, the Bible passed to Harry's uncle;[clarification needed] at the uncle's death Harry's brother and sister added the Bible to the Harry Elkins Widener Collection because it "had been bought for Harry and should be among his books." Yale also has a Gutenberg, though not in "quite as fine condition" as Harvard's, according to Harvard officials.[102]

- [9] As pointed out by snopes.com: "Harry Elkins Widener didn't die because he couldn't swim: he, like many other Titanic passengers who couldn't be accommodated by one of the too-few lifeboats, died from immersion in freezing water. The ability to swim wouldn't have helped him, because there was nowhere for him to swim to." [111]

- [120] John Shea was for forty years Widener's "guardian and familiar spirit". His mother had been a college "biddy" who (he said) "did professor C. T. Copeland's laundry for years",[120] and he began his own Harvard career in 1905 as a Gore Hall coatchecker. By his 1954 retirement as Widener's Stacks Superintendent, he was "perhaps the last of the legendary College characters",[37]: 58 renowned not only for leaving "no stone unthrown"—as he himself put it—in locating mis-shelved or otherwise errant books, but also for his "genius for such malapropisms [which] in fact, were generally the mot juste". These included references to "venereal blinds" and "osculating fans" in the Catalog Room, equipment that had "outlived its uselessness", a gift of a bottle of wine "as a momentum", and mention that Widener's head janitor "has a maniac for sweeping the basement." [3]

- [136] Eleanor Widener "had originally stipulated that no further memorials would be permitted within her library, but the war had softened her feelings on the matter. Too many Harvard men died in the conflict to ignore their loss—and further, it seems, Eleanor came to connect Harry's death with their sacrifice." (Battles)[B]: 63

- After his retirement Metcalf wrote that when planning the later Lamont Library, "I was still old fashioned enough to believe that, if women [would be permitted to use it] we should probably not have the small, unsupervised reading rooms that we were planning." [68]: 87

- [147][53] The quotation "He labored not for himself only ..." alludes to Ecclesiasticus 33:17.

- [44] "Before the renovation, the upper [stacks] floors smelled, in summer, of gently roasted books, while [the lowest floor] year-round offered the sporiferous scent usually associated with grottoes and Roman cellars." (Battles)[B]: 180 When Widener was built ventilation for books was emphasized, possibly to prevent mold; thus a slit ran along the base of every row of shelves, allowing air to flow from the floor below. Unfortunately books, papers and objects were prone to fall through these slits,[67]: 135 and "the whole installation might have been regarded as a large collection of chimneys that would help a fire to spread rapidly from floor to floor." The slits were later closed.[68]: 92–93

Sources and further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.