Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Water splitting

Chemical reaction From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

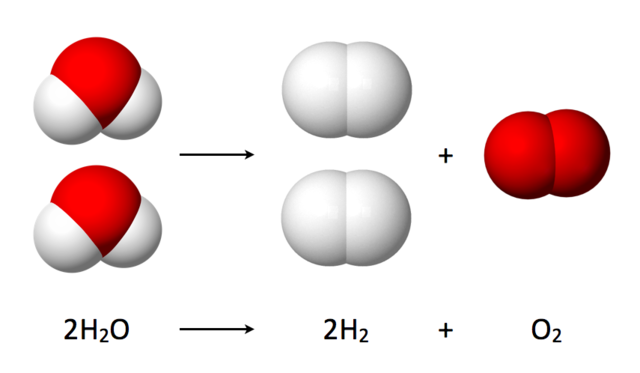

Water splitting is the chemical reaction in which water is broken down into oxygen and hydrogen:[1]

2 H2O → 2 H2 + O2

Efficient and economical water splitting would be a technological breakthrough that could underpin a hydrogen economy. A version of water splitting occurs in photosynthesis, but hydrogen is not produced. The reverse of water splitting is the basis of the hydrogen fuel cell. Water splitting using solar radiation has not been commercialized.

Remove ads

Electrolysis

Electrolysis of water is the decomposition of water (H2O) into oxygen (O2) and hydrogen (H2):[2]

Production of hydrogen from water is energy intensive. Usually, the electricity consumed is more valuable than the hydrogen produced, so this method has not been widely used. In contrast with low-temperature electrolysis, high-temperature electrolysis (HTE) of water converts more of the initial heat energy into chemical energy (hydrogen), potentially doubling efficiency to about 50%.[citation needed] Because some of the energy in HTE is supplied in the form of heat, less of the energy must be converted twice (from heat to electricity, and then to chemical form), and so the process is more efficient.[citation needed]

High-temperature electrolysis (also HTE or steam electrolysis) is a method for the production of hydrogen from water with oxygen as a by-product.

Remove ads

Water splitting in photosynthesis

A version of water splitting occurs in photosynthesis but the electrons are shunted, not to protons, but to the electron transport chain in photosystem II. The electrons are used to reduce carbon dioxide, which eventually becomes incorporated into sugars.

Photo-excitation of photosystem I initiates electron transfer to a series of electron acceptors, eventually reducing NADP+ to NADPH. The oxidized photosystem I captures electrons from photosystem II through a series of steps involving plastoquinone, cytochromes, and plastocyanin. Oxidized photosystem II oxidizes the oxygen-evolving complex (OEC), which converts water into O2 and protons.[3][4] Since the active site of the OEC contains manganese, much research has aimed at synthetic Mn compounds as catalysts for water oxidation.[5]

In biological hydrogen production, the electrons produced by the photosystem are shunted not to a chemical synthesis apparatus but to hydrogenases, resulting in formation of H2. This biohydrogen is produced in a bioreactor.[6]

Remove ads

Photoelectrochemical water splitting

Using electricity produced by photovoltaic systems potentially offers the cleanest way to produce hydrogen, other than nuclear, wind, geothermal, and hydroelectric. Again, water is broken down into hydrogen and oxygen by electrolysis, but the electrical energy is obtained by a photoelectrochemical cell (PEC) process. The system is also named artificial photosynthesis.[7][8][9]

Catalysis and proton-relay membranes are often the focus on development.[10]

Photocatalytic water splitting

The conversion of solar energy into hydrogen by means of water splitting process might be more efficient if it is assisted by photocatalysts suspended in water rather than a photovoltaic or an electrolytic system, so that the reaction takes place in one step.[11][12]

Radiolysis

Energetic nuclear radiation can break the chemical bonds of a water molecule. In the Mponeng gold mine, South Africa, researchers found in a naturally high radiation zone a community dominated by Desulforudis audaxviator, a new phylotype of Desulfotomaculum, feeding on primarily radiolytically produced H2.[13]

Thermal decomposition of water

Summarize

Perspective

In thermolysis, water molecules split into hydrogen and oxygen. For example, at 2,200 °C (2,470 K; 3,990 °F) about three percent of all H2O are dissociated into various combinations of hydrogen and oxygen atoms, mostly H, H2, O, O2, and OH. Other reaction products like H2O2 or HO2 remain minor. At the very high temperature of 3,000 °C (3,270 K; 5,430 °F) more than half of the water molecules are decomposed. At ambient temperatures only one molecule in 100 trillion dissociates by the effect of heat.[14] The high temperature requirements and material constraints have limited the applications of the thermal decomposition approach.

Other research includes thermolysis on defective carbon substrates, thus making hydrogen production possible at temperatures just under 1,000 °C (1,270 K; 1,830 °F).[15]

One side benefit of a nuclear reactor that produces both electricity and hydrogen is that it can shift production between the two. For instance, a nuclear plant might produce electricity during the day and hydrogen at night, matching its electrical generation profile to the daily variation in demand. If the hydrogen can be produced economically, this scheme would compete favorably with existing grid energy storage schemes. As of 2005, there was sufficient hydrogen demand in the United States that all daily peak generation could be handled by such plants.[16]

The hybrid thermoelectric copper–chlorine cycle is a cogeneration system using the waste heat from nuclear reactors, specifically the CANDU supercritical water reactor.[17]

Solar-thermal

Concentrated solar power can achieve the high temperatures necessary to split water. Hydrosol-2 is a 100-kilowatt pilot plant at the Plataforma Solar de Almería in Spain which uses sunlight to obtain the required 800 to 1,200 °C (1,070 to 1,470 K; 1,470 to 2,190 °F) to split water. Hydrosol II has been in operation since 2008. The design of this 100-kilowatt pilot plant is based on a modular concept. As a result, it may be possible that this technology could be readily scaled up to megawatt range by multiplying the available reactor units and by connecting the plant to heliostat fields (fields of sun-tracking mirrors) of a suitable size.[18]

Material constraints due to the required high temperatures are reduced by the design of a membrane reactor with simultaneous extraction of hydrogen and oxygen that exploits a defined thermal gradient and the fast diffusion of hydrogen. With concentrated sunlight as heat source and only water in the reaction chamber, the produced gases are very clean with the only possible contaminant being water. A "Solar Water Cracker" with a concentrator of about 100 m2 can produce almost one kilogram of hydrogen per sunshine hour.[19]

The sulfur–iodine cycle (S–I cycle) is a series of thermochemical processes used to produce hydrogen. The S–I cycle consists of three chemical reactions whose net reactant is water and whose net products are hydrogen and oxygen. All other chemicals are recycled. The S–I process requires an efficient source of heat.

More than 352 thermochemical cycles have been described for water splitting by thermolysis.[20] These cycles promise to produce hydrogen and oxygen from water and heat without using electricity.[21] Since all the input energy for such processes is heat, they can be more efficient than high-temperature electrolysis. This is because the efficiency of electricity production is inherently limited. Thermochemical production of hydrogen using chemical energy from coal or natural gas is generally not considered, because the direct chemical path is more efficient.

For all the thermochemical processes, the summary reaction is that of the decomposition of water:[21]

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads

![{\displaystyle {\ce {2H2O <=>[{\ce {Heat}}] 2H2{}+ O2}}}](http://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f87596dad9be266529ce624d24d420a7c5529226)