W. Eugene Smith

American photojournalist (1918–1978) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

William Eugene Smith (December 30, 1918 – October 15, 1978) was an American photojournalist.[1] He has been described as "perhaps the single most important American photographer in the development of the editorial photo essay."[2] His major photo essays include World War II photographs, the visual stories of an American country doctor and a nurse midwife, the clinic of Albert Schweitzer in French Equatorial Africa, the city of Pittsburgh, and the pollution which damaged the health of the residents of Minamata in Japan.[3] His 1948 series, Country Doctor, photographed for Life, is now recognized as "the first extended editorial photo story".[2]

W. Eugene Smith | |

|---|---|

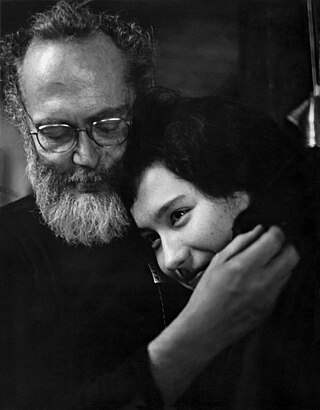

Smith and wife Aileen, 1974 (Photo by Consuelo Kanaga) | |

| Born | William Eugene Smith December 30, 1918 Wichita, Kansas, U.S. |

| Died | October 15, 1978 (aged 59) Tucson, Arizona, U.S. |

| Occupation | Photojournalist |

| Years active | 1934–1978 |

| Spouse | Carmen Martinez 1941, Aileen Mioko 1971 |

| Partner | Sherry Suris 1974 |

| Children | Marissa 1942, Juanita, Patric, Kevin 1956 |

Life and early work

Summarize

Perspective

William Eugene Smith was born in Wichita, Kansas, on December 30, 1918, to William H. Smith and his wife Nettie (née Lee). Growing up, Smith had become fascinated by flying and aviation. When Smith was 13, he asked his mother for money to buy photographs of airplanes. His mother instead lent him her camera and encouraged him to visit a local airfield to take his own photos. When he returned with his exposed film, she developed the pictures for him in her own improvised darkroom.[4]

By the time he was a teenager, photography had become his passion; he photographed sports activities at Cathedral High School and at the age of 15 his sports photos were published by Vigil Cay, sports editor at the Wichita Press.[5] On July 25, 1934, The New York Times published a photo by Smith of the Arkansas River dried up into a plate of mud, evidence of the extreme weather events that were devastating the Midwest. These weather conditions had a disastrous effect on agriculture. Smith's father, who was a grain dealer, saw his business head towards bankruptcy and he committed suicide.[5]

Smith graduated from the Wichita North High School in 1936. His mother used her Catholic church connections to enable Smith to obtain a photography scholarship which helped to fund his tuition at the University of Notre Dame, but at the age of 18 he abruptly quit university[6] and moved to New York City. By 1938 he had begun to work for Newsweek where he became known for his perfectionism and thorny personality. Smith was eventually fired from Newsweek; he later explained Newsweek wanted him to work with larger format negatives but he refused to abandon the 35 mm Contax camera he preferred to work with.[7] Smith began to work for Life magazine in 1939, quickly building a strong relationship with then picture editor Wilson Hicks.[8] Smith married Carmen in 1941 with whom he had four children, their first Marissa in 1942, Juanita, K. Patrick, 1943, Shana,1953 and Kevin in 1956. It is unknown when they divorced. He married Aileen in 1971 and again unknown if they divorced, but he ended his relationship with Aileen as he began a relationship with Sherry Suris and moved in with her after completing the Minamata book in 1974, as laterly mentioned below in New York.

War work

Summarize

Perspective

In September 1943, Smith became a war correspondent for Ziff-Davis Publishing and also supplied photos to Life magazine. Smith took photos on the front lines in the Pacific theater of World War II. He was with the American forces during their island-hopping offensive against Japan, photographing U.S. Marines and Japanese prisoners of war at Saipan, Guam, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa.[9] Smith's awareness of the brutality of the conflict sharpened the focus of his ambition. He wrote "You can't raise a nation to kill and murder without injury to the mind... It is the reason I am covering the war for I want my pictures to carry some message against the greed, the stupidity and the intolerances that cause these wars and the breaking of many bodies." Ben Maddow wrote: "Smith's photographs of 1943 through 1945 show his swift development from talent to genius."[10] In 1945, Smith was seriously injured by mortar fire while photographing the Battle of Okinawa.[11]

In 1946, he took his first photograph since being injured: a picture of his two children walking in the garden of his home which he titled The Walk to Paradise Garden. The photograph became famous when Edward Steichen used it as one of the key images in the exhibition The Family of Man, which Steichen curated in 1955.[12] After spending two years undergoing surgery, Smith continued to work at Life until 1955.[13]

1950s

Summarize

Perspective

Between 1948 and 1954 Smith photographed for Life magazine a series of photo essays with a humanist perspective which laid the basis of modern photojournalism, and which were, in the estimate of Encyclopædia Britannica, "characterized by a strong sense of empathy and social conscience."[14]

In August 1948 Smith photographed Dr. Ernest Ceriani in the town of Kremmling, Colorado, for several weeks, covering the doctor's arduous work in a thinly populated western environment, grappling with life and death situations. (One of the most vivid images shows Ceriani looking exhausted in a kitchen, having performed a Caesarean section during which both mother and baby died.)[2] The essay Country Doctor was published by Life on September 20, 1948.[15] It has been described by Sean O'Hagan as "the first extended editorial photo story".[2]

In late 1949, Smith was sent to the UK to cover the General Election, when the Labour Party, under Clement Attlee, was re-elected with a tiny majority.[16] Smith also travelled to Wales where he photographed a series of studies of miners in South Wales Valleys. Critics have compared Smith's work to similar studies made by Bill Brandt.[16] In a documentary made by BBC Wales, Dai Smith located a miner who described how he and two colleagues had met Smith on their way home from work at the pit and had been instructed on how to pose for one of the photographs published in Life.[17][18]

From Wales, Smith travelled to Spain where he spent a month in 1950, photographing the village of Deleitosa, Extremadura, focusing on themes of rural poverty.[16] Smith attracted the suspicion of the local Guardia Civil, until he finally made an abrupt exit across the border to France. A Spanish Village was published in Life on April 9, 1951, to great acclaim. Ansel Adams wrote Smith a letter of praise, which Smith carried in his pocket for three years, unable to write a reply.[19]

In 1951, Smith persuaded Life editor Edward Thompson to let him do a photo-journalistic profile of Maude E. Callen, a black nurse midwife working in rural South Carolina. For weeks Smith accompanied Callen on her exhausting schedule, rising before dawn and working into the evening. The essay Nurse Midwife was published in Life on December 3, 1951. It was well received and resulted in thousands of dollars in donations to create the Maude Callen Clinic, which opened in Pineville, South Carolina in May 1953, with Smith present at the ceremony.[20][21]

In 1954, Smith photographed an extensive photo-essay about the work of Albert Schweitzer at his clinic at Lambaréné in Gabon, West Africa.[22] It was later revealed that one of his most famous images had been extensively manipulated.[23] Smith made many layouts of his Schweitzer pictures which he submitted to Life, but the final layout of the story published on November 15, 1954, entitled A Man of Mercy, angered Smith because editor Edward Thompson used fewer pictures than Smith wanted, and Smith thought the layout crude. He sent a formal 60-day notice of resignation letter to Life in November 1954.[24]

After leaving Life magazine, Smith joined the Magnum Photos agency in 1955. There he was commissioned by Stefan Lorant to produce a photographic profile of the city of Pittsburgh. The project was supposed to take him a month and to produce 100 images. It ended up occupying more than two years and producing 13,000 photographic negatives. The intended book was never delivered to Lorant, and Smith's obsessive work was bailed out by money from Magnum, causing strain between Smith and the photo-journalist collective.[25]

Jazz Loft Project

Summarize

Perspective

In 1957, Smith left his wife Carmen and their four children in Croton-on-Hudson and moved into a loft space at 821 Sixth Avenue in Midtown Manhattan which he shared with David X. Young, Dick Cary, and Hall Overton.[26][27] Smith laid down an intricate network of microphones and obsessively took photographs and recorded jazz musicians playing in the loft space, including Thelonious Monk, Zoot Sims and Rahsaan Roland Kirk. From 1957 to 1965, Smith made approximately 4,000 hours of recordings on 1,740 reel-to-reel tapes[26] and nearly 40,000 photographs in the loft building in Manhattan's wholesale flower district.[28] The tapes also contain recorded street noise in the flower district, late-night radio talk shows, telephone calls, television and radio news programs, and random loft dialogues among musicians, artists, and other Smith friends and associates.[27] The Jazz Loft Project, devoted to preserving and cataloging the works of Smith, is directed by Sam Stephenson at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, in co-operation with the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona and the Smith estate.[2][27][28][29]

In August 1970, at the age of 51, Smith met Aileen Sprague, who would later become his wife. She served as a translator for Smith when he was interviewed in a Fujifilm commercial. Aileen was the daughter of a Japanese mother and an American father, raised in Tokyo before they moved to the United States when she was 11. At the time of meeting Smith she was 20 years old and went to Stanford University. Only a week after meeting, Smith asked her to become his assistant and live with him in New York. Aileen agreed, dropped out of university and began living with Smith.

Japan and Minamata

Summarize

Perspective

In the fall of 1970, Kazuhiko Motomura, a friend of Smith, moved to the United States. He proposed to Smith and Aileen to visit Japan and cover the Minamata disease. They accepted the invitation and arrived in Japan on August 16, 1971, where they married 12 days later.

Between September 1971 and October 1974, they rented a house in Minamata, both a fishing village and a "one company" industrial city in Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan. There, they created a long-term photo-essay on Minamata disease, the effects of mercury poisoning caused by a Chisso factory discharging heavy metals into water sources around Minamata.[30]

In January 1972, Smith accompanied activists who were meeting representatives of the Chisso trade unionists at Chiba, to ask why union workers were used by the company as bodyguards. The group was attacked by Chisso Company employees and members of the union local who beat Smith up, badly damaging his eyesight.[31][32] Smith and Aileen continued to work together to complete the Minamata project, despite the fact that Aileen informed Smith she was divorcing him as soon as the book was finished. They were supported by the publisher Lawrence Schiller and finished the book in Los Angeles.[33]

The book was published in 1975 as Minamata, Words and Photographs by W. Eugene Smith and Aileen M. Smith. Its centerpiece photograph and one of his most famous works, Tomoko and Mother in the Bath, taken in December 1971, drew worldwide attention to the effects of Minamata disease.[34] The photograph shows a mother cradling her severely deformed daughter in a traditional Japanese bath house. The photograph was the centerpiece of a Minamata disease exhibition held in Tokyo, in 1974.[34] In 1997, Aileen M. Smith withdrew the photo from circulation in accordance with Tomoko's parents' wishes.[34]

In 2020, the film Minamata dramatized the story of Smith's documentation of the pollution and the ensuing protests and campaign in Japan. Johnny Depp played W. Eugene Smith and Minami played Aileen.[35][36]

Move to Arizona and death

Smith returned from his stay in Minamata, Japan, in November 1974, and, after completing the Minamata book, he moved to a studio in New York City with a new partner, Sherry Suris. Smith's friends were alarmed by his deteriorating health and arranged for him to join the teaching faculty of the Art Department and Department of Journalism at the University of Arizona.[37] Smith and Suris moved to Tucson, Arizona in November 1977. On December 23, 1977, Smith suffered a massive stroke, but made a partial recovery and continued to teach and organize his archive. Smith suffered a second stroke and died on October 15, 1978. He was cremated and his ashes interred in Crum Elbow Rural Cemetery, Hyde Park, New York.[38]

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Summarizing Smith's achievements, Ben Maddow wrote:

"His vocation, he once said, was to do nothing less than record, by word and photograph, the human condition. No one could really succeed at such a job: yet Smith almost did. During his relatively brief and often painful life, he created at least fifty images so powerful that they have altered the perception of our history."[39]

Writing in The Guardian in 2017, Sean O'Hagan described Smith as "perhaps the single most important American photographer in the development of the editorial photo essay."[2]

According to the International Center of Photography, "Smith is credited with the developing the photo essay to its ultimate form. He was an exacting printer, and the combination of innovation, integrity, and technical mastery in his photography made his work the standard by which photojournalism was measured for many years."[40]

In 1984 Smith was posthumously inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum.[41]

The Big Book

The Big Book (The Walk to Paradise Garden) is a conceptual photobook that Smith worked on from 1959 until his death, intending to serve as retrospective sum of his work as well as a reflection of his life philosophies. Considered "unviable and non-commercial" at the time, due to having 380 pages and 450 images in two volumes, it was unpublished in his lifetime but was finally published in a facsimile reproduction in 2013 by the University of Texas Press with an added third volume of essays and texts.[42] The work includes two of Smith's original volumes which present his imagery not according to story, as they would have been published at the time of their creation, but rather according to Smith's own creative process. The University of Texas publication comes with a third book included in the slip-case, offering contemporary essays and notes.[43]

W. Eugene Smith Memorial Fund

The W. Eugene Smith Memorial Fund promotes "humanistic photography".[44] Since 1980, the fund has awarded photographers for exceptional accomplishments in the field.

Notable photographs and photo-essays

- 1944 photograph[45] in which a wounded infant is found by an American soldier on Saipan.

- 1945 photograph in which Marines blow up a Japanese cave on Iwo Jima, published on the cover of Life, April 9, 1945.

- "The Walk to Paradise Garden" (1946) – single photograph of his two children walking hand in hand towards a clearing in woods. It was the closing image in the 1955 Museum of Modern Art exhibition, The Family of Man,[46] organized by Edward Steichen with 503 photographs, by 273 photographers from 68 countries.

- Country Doctor[47] (1948) – photo essay on Ernest Ceriani in the small Colorado town of Kremmling. It was described by Sean O'Hagan as "the first extended editorial photo story".[2]

- "Dewey Defeats Truman" (1948) - single photograph of Harry S. Truman on the back of the presidential train in Saint Louis holding up a day old copy of the Chicago Daily Tribune with the prominent (and incorrect) headline "Dewey Defeats Truman"

- Spanish Village (1950) – photo essay on the small Spanish town of Deleitosa.

- Nurse Midwife (1951) – photo essay on midwife Maude E. Callen in South Carolina.[48][21]

- A Man of Mercy (1954) – photo essay on Albert Schweitzer and his humanitarian work in French Equatorial Africa.

- "Pittsburgh" (1955–1958) – three-year-long project on the city, hired initially by photo editor Stefan Lorant for a three-week assignment.

- Haiti 1958–1959 – photo essay on a psychiatric institute in Haiti.[49]

- "Tomoko and Mother in the Bath" (1971)[50] – the centerpiece photograph in Minamata, a long-term photo essay on Minamata disease. The photograph depicts a mother cradling her severely deformed, naked daughter in a traditional Japanese bathing chamber.[34]

Publications

- Michael E. Hoffman, Minor White (eds.): W. Eugene Smith: His Photographs and Notes. An Aperture Monograph. New York: Aperture, 1973. ISBN 0-912334-09-6. Afterword by Lincoln Kirstein.

- W. Eugene Smith and Aileen M. Smith: Minamata. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1975.

- William S. Johnson (ed.): W. Eugene Smith: Master of the Photographic Essay. New York: Aperture, 1981. ISBN 0-89381-070-3. Foreword by James L. Enyeart.

- Ben Maddow: Let Truth Be the Prejudice: W. Eugene Smith, His Life and Photographs. New York: Aperture, 1985. ISBN 0-89381-179-3. Illustrated biography, exhibition catalogue. With an afterword by John G. Morris.

- Jim Hughes: W. Eugene Smith: Shadow & Substance: the Life and Work of an American Photographer. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1989. ISBN 0-07-031123-4.

- Gilles Mora, John T. Hill (eds.): W. Eugene Smith: Photographs 1934–1975. New York: Abrams, 1998. ISBN 0-8109-4191-0. With texts by Mora, "W. Eugene Smith: the Arrogant Martyr", Serge Tisseron, "What Is a Symbolic Image?", Alan Trachtenberg, "W. Eugene Smith's Pittsburgh: Rumours of a City", Gabriel Bauret, "The Influences of a Legend", and Hill, "W. Eugene Smith: His Techniques and Process". The texts by Mora, Bauret and Tisseron were translated from the French by Harriet Mason (French edition by Seuil, Paris).

- Simultaneous UK edition: W. Eugene Smith: The Camera as Conscience. London: Thames & Hudson 1998. ISBN 0-500-54225-2.

- Sam Stephenson (ed.): The Jazz Loft Project: Photographs and Tapes of W. Eugene Smith from 821 Sixth Avenue, 1957–1965. New York: Knopf 2009. ISBN 978-0-226-82700-1.

- The Big Book. Two facsimiled volumes of the original marqettes, additional third volume with essays and texts. Tucson: Center for Creative Photography, University of Texas 2013. ISBN 0-292-75468-X, OCLC 892892442.

Films

- W. Eugene Smith: Photography Made Difficult (Home Vision, 1989) – 87 minutes. Produced by Kirk Morris, directed by Gene Lasko and written by Jan Hartman. ISBN 9780780007680. Originally broadcast as a segment of American Masters.

- The Jazz Loft According to W. Eugene Smith. Written, produced and directed by Sara Fishko. New York: WNYC/Lumiere 2015.[51][52]

- The 2020 feature film Minamata focuses on Smith (portrayed by Johnny Depp) and his involvement in documenting the Minamata disease in 1971.[53]

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.