Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

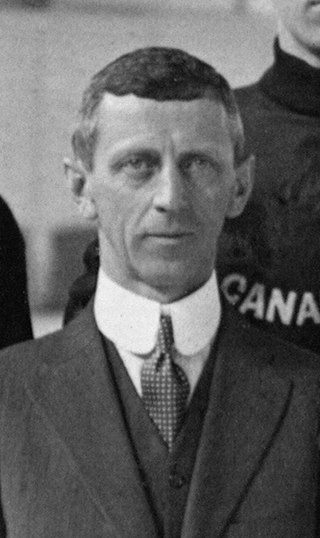

W. A. Hewitt

Canadian sports executive and journalist (1875–1966) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

William Abraham Hewitt (May 15, 1875 – September 8, 1966) was a Canadian sports executive and journalist, also widely known as Billy Hewitt.[a] He was secretary of the Ontario Hockey Association (OHA) from 1903 to 1966, and sports editor of the Toronto Daily Star from 1900 to 1931. He promoted the establishment of the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA), then served as its secretary-treasurer from 1915 to 1919, registrar from 1921 to 1925, registrar-treasurer from 1925 to 1961, and a trustee of the Allan Cup and Memorial Cup. Hewitt standardized player registrations in Canada, was a committee member to discuss professional-amateur agreements with the National Hockey League, and negotiated working agreements with amateur hockey governing bodies in the United States. He oversaw referees within the OHA, and negotiated common rules of play for amateur and professional leagues as chairman of the CAHA rules committee. After retiring from journalism, he was the managing-director of Maple Leaf Gardens from 1931 to 1948, and chairman of the committee to select the inaugural members of the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1945.

Hewitt was a member of the Canadian Olympic Committee from 1920 to 1932, helped select athletes for the Summer and Winter Olympics, and was the head of mission for Canada at the 1928 Winter Olympics. He served as the financial manager for the Canada men's national ice hockey team which won Olympic gold medals in 1920, 1924, and 1928; while sending reports on the Olympic Games to Canadian newspapers. He introduced the CAHA rules of play to the Ligue Internationale de Hockey sur Glace in 1920, and refereed the first game played in the history of ice hockey at the Olympic Games. He also served on several committees for the Amateur Athletic Union of Canada, and including chairman of the registration committee which oversaw the reinstatement of professionals as amateurs.

In Canadian football, Hewitt managed the Toronto Argonauts from 1905 to 1907, served as vice-president of the Ontario Rugby Football Union, and helped organize the meeting which established the Inter-provincial Rugby Football Union in 1907. He was president of the Canadian Rugby Union from 1915 to 1919, sought to implement uniform rules of play across Canada, and was a referee for collegiate and inter-provincial games. In horse racing, Hewitt was a patrol judge at Woodbine Race Course, was a steward of the Incorporated Canadian Racing Association for 31 years, then a steward of the Ontario Racing Association for 14 years.

Hewitt was the father of radio sports announcer Foster Hewitt, and the grandfather of television sports commentator Bill Hewitt. Hewitt guided his son into radio, and together they called the 1925 King's Plate, the first horse race to be broadcast on radio. Later in life, Hewitt published his memoirs, had two arms broken in a car accident that killed his wife, and a heart attack while on a tour of Czechoslovakia with the Winnipeg Maroons. He was a life member of both the OHA and the CAHA, the guest of honour at two testimonial dinners, and multiple ice hockey trophies were named for him including the Dudley Hewitt Cup. He was inducted into the builder category of the Hockey Hall of Fame, the International Hockey Hall of Fame, and the IIHF Hall of Fame.

Remove ads

Early life and family

Summarize

Perspective

William Abraham[b][c] Hewitt was born on May 15, 1875, in Cobourg, Ontario, the son of a clothing merchant.[2][13][15] His parents James Thomas Hewitt and Sarah Hopkins had Irish-Canadian heritage.[13] Hewitt's mother was a schoolteacher born in Northern Ireland, and his father was a salesman born in Canada.[10] The family relocated to Toronto circa 1879, when Hewitt was age 4.[2][10] Hewitt's father worked as an inspector on horse-drawn carriages in Toronto,[16] then died when Hewitt was age 8.[10]

As a youth, Hewitt played team sports sparingly due to his small stature,[15] and learned the sport of boxing from his brothers.[17] At age 12, he pitched batting practice to professional baseball players at Sunlight Park, and later played baseball for the Victorias at Jesse Ketchum Park.[18] His first job was as a newspaper boy for the Toronto Empire, as he and his brothers earned money for the family after their father died.[19] Hewitt's subsequent jobs as a youth included sorting and polishing apples, a messenger at a law office, a labourer at the Eckhardt Casket Company, and as a stock boy at a grocery store owned by his uncle.[20] Hewitt completed his secondary school education at Jarvis Collegiate Institute.[21]

Hewitt was a member of the Anglican Church of Canada, and married Flora Morrison Foster on October 2, 1897, at the Church of the Holy Trinity.[14][22] They met while singing in the church choir, and she was the daughter of a local hardware merchant.[22] They had one daughter, Audrey (born 1898), and one son, Foster Hewitt (born 1902).[22][23]

Remove ads

Journalism career

Summarize

Perspective

Toronto News

Hewitt began working in newspapers at age 14,[9] and earned C$4 per week as a copy boy with the Toronto News.[2][15] The paper's city editor left Hewitt in charge one afternoon, with instructions to fire a young reporter named William Lyon Mackenzie King if he showed up. Hewitt sat at the editor's desk, when King showed up a few minutes later and resigned before Hewitt could tell him he was fired. Later in life, Hewitt regretted the missed opportunity to fire the future prime minister of Canada.[24]

At age 15, Hewitt began his journalism career writing for the Toronto News, with a salary of $10 per week. His first assignment was reporting on the strapping of a convicted sex offender at the Toronto Central Prison.[25] He later reported on baseball and lacrosse,[23] events at Massey Hall, and regularly covered the police and court beat in Toronto.[26] In 1894, Hewitt reported on his first Queen's Plate for horse racing.[27] He became the sports editor of the Toronto News at age 20, and gathered his information through multiple contacts he made in the sports world.[28] His boss at the Toronto News, H. C. Hocken, gave Hewitt a pay raise to $20 per week as the sports editor.[29]

During the late-1890s, Hewitt and business partners arranged day trips by train for spectators to attend the Fort Erie Race Track, and the Kenilworth Racetrack in Buffalo, New York.[27] In addition to sports, Hewitt covered Toronto City Council meetings, and reported on the opening of Toronto City Hall in 1899.[30] He was also the press agent for the Grand Opera House during the late-1890s.[31]

Montreal Herald

Publisher Joseph E. Atkinson convinced Hewitt to transfer to the Montreal Herald as the sports editor, with a starting salary of $25 per week, and the promise to cover Hewitt's travel expenses to and from Montreal on weekends, and future advancement if the paper prospered.[32] He accepted the offer and learned that there was a bitter rivalry between the owners of the Montreal Herald and the Montreal Star. He subsequently declined a twofold pay raise to join the Montreal Star due to his loyalty to Atkinson.[33] Hewitt wrote in his memoirs that when he introduced nets to hockey goalposts in 1899, it increased the tension between the Montreal newspapers, and that the idea was ridiculed by the Montreal Star and the Montreal Gazette. Hewitt arranged for the nets to be used in a local game between the Montreal Victorias and the Montreal Shamrocks, after taking inspiration from fellow journalist Francis Nelson, to resolve disputed goals.[34]

Toronto Daily Star

Hewitt returned to Toronto, and was the sports editor of the Toronto Daily Star from 1900 to 1931.[11][35] His transition from Toronto to Montreal and return took less than three months, when Atkinson purchased the Toronto Daily Star and Hewitt followed him to Toronto in January 1900.[36] Hewitt sought for his sports staff to write articles which were accurate, brief, and included the result of the game in the first paragraph, such that it was easier to shorten the article if more page space was sold for newspaper advertising.[37]

As the sports editor, his favourite topics were ice hockey and Canadian football.[38] He also regularly covered baseball, boxing, horse racing, and lacrosse;[38][39] in addition to sports played by the Canadian Interuniversity Athletic Union.[40] He also attended and wrote about the boxing match on July 4, 1919, when Jack Dempsey won the heavyweight title from Jess Willard.[2]

During the early-1900s, Hewitt reported on the Toronto Maple Leafs baseball team in the International League, and travelled with the team to spring training and some road games.[41] Also during the early-1900s, Hewitt shared in a business venture which operated a baseball World Series scoreboard at several theatres in Toronto. The scoreboard lights for hits, baserunners, and game play, relayed by a telegrapher, to provide patrons with an in-theatre recreated version of a live baseball game. Due to the increasing costs of wire services and renting the buildings, the boards were later used outside of the Toronto Daily Star building instead.[42]

In 1901, Hewitt began publishing horse racing results from tracks in the United States, in addition to results from tracks in Ontario.[27] In 1910, he was charged with breach of racing laws for "printing, publishing, and selling a daily racing record".[43] He pleaded not guilty while sale of the paper stopped,[43] and was subsequently fined $100 for violation of the Miller Act.[44][d] In 1921, he was charged with "advertising, publishing, exhibiting and selling" a horse racing form in Toronto, which was alleged to assist in placing wagers on races.[46] Fellow journalist Francis Nelson argued that the form assisted sports editors in reporting the horse's record, that it was also useful to horse breeders, and that it did not specialize in betting any more than newspapers.[46] Hewitt was later convicted and fined $25, despite that the judge stated Hewitt had not knowingly broken any law.[47][48]

Hewitt was interested in connecting newspapers to radio broadcasts, and took his son Foster to a radio convention at the General Motors Building in 1921.[49] He then guided his son into a career in radio, as a more popular medium for sport.[2][50]

In October 1931, Hewitt resigned as sports editor of the Toronto Daily Star and was succeeded by Lou Marsh, his assistant of 26 years.[7][51] During his journalism career, Hewitt preferred to write his stories by hand and never used a typewriter.[52] Upon his retirement, The Kingston Whig-Standard described Hewitt as, "a most prolific writer, a man with a keen knowledge of all sports, no matter what they are, and above all, at all times one of the fairest writers newspaperdom ever knew".[51]

Remove ads

Ontario Hockey Association

Summarize

Perspective

Hewitt became involved in ice hockey as a player and on-ice official, and reported on the game as a journalist.[53] He was the representative for the Toronto Wellingtons and the Toronto St. George's teams at meetings of the Ontario Hockey Association (OHA) during the late-1890s. At the urging of several clubs in Toronto, Hewitt was convinced to stand for election to the OHA executive.[54] He was elected secretary of the OHA on December 8, 1903,[2] to succeed fellow journalist William Ashbury Buchanan.[55] As secretary, Hewitt received an honorarium for expenses which was increased annually from $200 as of 1903.[23] He was chairman of the OHA schedule committee;[56] and sat on sub-committees to divide teams into groups for league play, and review registrations by players requesting to change teams.[57]

During the early-1900s, Hewitt, John Ross Robertson, and the OHA president at the time, sat on a standing committee to review protests and suspensions. Hewitt wrote in his memoirs that the committee was jokingly known as the "Three White Czars", because of their power to "exile offenders to hockey's Siberia".[58] During the 1904–05 season, the OHA declined a request by Cyclone Taylor to transfer from Listowel to Thessalon, with the decision being relayed by Hewitt.[59] Taylor recalled the incident in his autobiography, and wrote that Hewitt telephoned him with an invitation to play for the Toronto Marlboros senior team. Taylor declined the offer since he wanted to stay at home where he had a job, and stated that Hewitt responded, "If you won't play for the Marlies, you won't play anywhere".[59] Seventy years later, Taylor said that he never forgave Hewitt for the season's suspension.[59]

Hewitt represented the OHA executive committee during the playoffs, to witness the games any incidents that the executive may have to deal with, and to collect the OHA's share of the gate receipts.[60] During a playoffs game in Smiths Falls in 1905, Hewitt arrived late when he train was delayed in a snowfall, then rink management refused to handover the gate receipts to Hewitt when the game did not complete due to on-ice incidents. The next day, Hewitt met with James Whitney, the premier of Ontario, who ordered the local clerk to hand over the money promptly.[60]

Referees and playing rules

As the secretary, Hewitt was the de facto referee-in-chief of the OHA.[61] He scheduled the referees for playoffs games in Ontario,[62] and was empowered to appoint referees for league games as of 1924, instead of the two teams agreeing on a referee.[63] He spoke annually at referee meetings to review interpretations of new and existing rules of play, and sought consistency and more strict enforcement of the rules when dealing with dissent and physical play.[64] In 1951, he supported the implementation of monetary fines for players who verbally abused on-ice officials.[65]

Professionalism and arena contracts

In 1924, the OHA voted to keep its ban on professional coaches in amateur hockey.[63] When Queen's University at Kingston hired a full-time athletic director, Hewitt felt that the OHA should allow the director's involvement with the hockey team despite him being a paid professional. Hewitt proposed an amendment to the constitution which would allow the executive to scrutinize any coach and decide on the registration. The amendment was rejected by delegates who remained against any professionals in the OHA.[66] Two years later, Hewitt brought up the issue again and argued that, "the original intention of this rule was to control the [professional] coach, not exterminate him".[67] His constitutional amendment was subsequently approved in the late-1920s.[67]

When the OHA contract with Arena Gardens was up for renewal in the late-1920s, some executives preferred the Ravina Gardens where teams could get 50 per cent of the gate receipts, compared to only 35 per cent of the gate receipts at the Arena Gardens. Hewitt argued that 35 per cent of a larger arena in an established part of the city would be more profitable than 50 per cent of a smaller arena under construction in a newer part of the city. Hewitt promised to negotiate a better deal, in exchange for the contract with Arena Gardens to be renewed on a year-by-year basis.[68] Hewitt subsequently became an influence on Conn Smythe's decision to build Maple Leaf Gardens.[50]

Hewitt retired from journalism and became the managing-director of Maple Leaf Gardens, on October 17, 1931, and oversaw all events other than hockey[7][69] The OHA signed multiple five-year contracts with the Gardens, in which all Toronto-based teams in the OHA played home games at the arena, except for the University of Toronto teams.[70][71] He remained managing-director of the Gardens until 1948, and attended every professional and amateur hockey game at the arena during his tenure.[15]

In 1933, Frank J. Selke testified in court that the Toronto Marlboros had a proposed agreement to guarantee its finances by the Toronto Maple Leafs. The agreement went unsigned when Hewitt voiced opposition to the financial support of amateur teams by professional teams.[72] Despite concerns from some that Hewitt was connected to professional hockey in his position at Maple Leaf Gardens, the OHA executive upheld his eligibility to be the secretary, since he had no say into the management of the Toronto Maple Leafs.[73]

Later years and retirement

During World War II, Hewitt oversaw assistance by the OHA to charities in Toronto which raised funds to support the war effort, including the local Canadian Red Cross.[75]

In January 1948, the OHA hired George Panter as an assistant secretary to reduce the workload on Hewitt, then later made Panter its business manager to oversee day-to-day operations. Hewitt retained his office at Maple Leaf Gardens where he kept the OHA's records, despite that a new office was opened across the road in a Canadian Bank of Commerce building. Bill Hanley became the business manager in 1951, and Hewitt's role gradually decreased.[74] The OHA established a permanent referee-in-chief position in 1952, and lessened the workload on Hewitt.[61]

Hewitt was acclaimed as secretary of the OHA for the 1965–66 season, his final election to the position.[76] He retired in May 1966, and the OHA transferred the secretary's duties to Bill Hanley, and renamed his position from business manager to secretary manager.[77][78]

Remove ads

Canadian Amateur Hockey Association

Summarize

Perspective

As the sports editor of the Toronto Daily Star, Hewitt promoted the proposal by the Manitoba Hockey Commission to establish a national body to govern amateur hockey.[79] The Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA) was founded on December 4, 1914, then began organizing national playoffs for the Allan Cup awarded to the champion of senior ice hockey, and drafted player eligibility and registration rules.[80]

Secretary, 1915 to 1919

When OHA president James T. Sutherland was elected president of the CAHA in December 1915, he appointed Hewitt as the CAHA secretary.[81] Sutherland then served in Europe with the Canadian Expeditionary Force during World War I, and Hewitt worked alongside OHA executive J. F. Paxton to keep the CAHA functional.[82][83] Hewitt conducted business as needed by mail-in votes, without holding annual elections or meetings due to prohibitive costs during war time austerity measures.[83][84] He assisted Allan Cup trustees to schedule national playoffs for the trophy,[85] and collaborated with Saskatchewan Amateur Hockey Association secretary W. C. Bettschen on drafting uniform rules for the competition.[86]

The Memorial Cup was established for the junior ice hockey championship of the CAHA as of 1919.[87] Hewitt assisted with scheduling its playoffs games,[88] and was subsequently named one of the cup's trustees.[50] In March 1919, the CAHA held its first annual meeting after a four-year hiatus, and adopted uniform rules for Allan Cup competition, and sought to form an alliance with senior hockey in the United States. At the same meeting, Hewitt was succeeded as CAHA secretary by W. C. Bettschen.[89] In October 1919, Hewitt and Paxton reached an agreement with the International Skating Union of the United States to govern and resume international games which halted during the war.[90]

Registrar, 1921 to 1925

In October 1921, the CAHA established a national registration committee and named Hewitt its registrar. The committee included the registrar, the sitting president, and two members each from Eastern and Western Canada; and aimed to investigate all registrations to exclude professionals and reduce the number of players transferring teams solely for hockey instead of employment.[91] The CAHA also wanted to eliminate Canadian players going to American-based teams for one season then returning.[92] Hewitt then implemented standard registration and transfer forms completed in triplicate, including copies for the player's team, the local governing body, and the CAHA registrar.[93] He also served as the CAHA's alternate representative to the Amateur Athletic Union of Canada (AAU of C), the governing body for amateur sports in Canada.[94]

In 1922, the CAHA accepted the Hamilton B. Wills Trophy as the senior hockey championship of North America, which saw the Allan Cup champion challenge the United States Amateur Hockey Association (USAHA) champion in a playoffs series. Hewitt was named one of the cup's trustees and assisted in scheduling the international games.[95][96] In 1923, Hewitt and J. F. Paxton collaborated to negotiate an agreement to govern the migration of senior hockey players to and from the USAHA,[96] and a proposal for the CAHA to assume control of the Allan Cup.[93] The trustees of the Allan Cup remained in control of the trophy, but agreed that proceeds from gate receipts for the Allan Cup playoffs would be held in trust and expended as requested by the CAHA.[96]

Registrar-treasurer, 1925 to 1961

The CAHA appointed Hewitt to the newly created registrar-treasurer position in March 1925, adding financial oversight to his duties in addition to the registration committee.[97] In 1929, Hewitt as the registrar-treasurer, and Fred Marples as the secretary, were made permanent positions on the CAHA executive committee.[98][99] When the George Richardson Memorial Trophy was established the junior hockey champion of Eastern Canada in 1932, Hewitt was made one of its trustees.[100]

In 1937, the CAHA made the registrar-treasurer and secretary positions non-permanent members of the executive to be filled by appointment,[101] with Hewitt re-appointed to be the registrar-treasurer.[102] In 1938, the CAHA removed voting power from the registrar-treasurer and secretary and positions, making the positions administrative only.[103] In April 1939, Hewitt was one of several guest speakers at the CAHA's silver jubilee, and gave introductions for each 11 of the 13 past presidents in attendance.[104]

Hewitt was chairman of the CAHA finance committee during World War II. He oversaw monetary gifts to the Government of Canada and the purchase of victory bonds to help with the war effort, and grants towards the development of minor ice hockey.[105][106] CAHA president Frank Sargent chose to host the Memorial Cup finals at Maple Leaf Gardens during the war to generate the greatest profit to reinvest into hockey in Canada.[107] Hewitt noted that Maple Leafs Gardens attracted large crowds to junior hockey, compared to Winnipeg, Regina and Edmonton, which were hotbeds for junior hockey in Western Canada, but their rinks had lesser spectator capacity.[108]

Player registrations

In 1925, the CAHA and OHA were determined to stop players from moving about the country solely for hockey. After the CAHA set its residency deadline to be May 15 instead of August 1, Hewitt advised that all players must establish bona fide residency to play within the CAHA.[97][109] The CAHA further tightened its residency deadline to January 1, as of the 1932–33 season.[110]

During the 1930s, the CAHA was faced with players returning from professional tryouts without signing a contract. The AAU of C had a policy that such players would be classified as professional and ineligible for amateur play in the same season.[110][111] Since that policy had not been enforced before, CAHA president Jack Hamilton ruled that those players' cards would be cancelled without penalty to the team.[111] When the AAU of C ruled in 1933 that anyone who had not played professional hockey in three years could apply for reinstatement as an amateur, Hewitt interpreted that the intent was to allow former professionals who were not "undesirables" to return to amateur hockey.[112]

In an effort to eliminate the "hockey tourist" in 1934, CAHA president E. A. Gilroy decreed that no player would be permitted to transfer between branches of the CAHA after January 1, without residency being established.[113] Hewitt and the registration committee subsequently allowed transfers after January 1 only for those playing on college teams, or legitimate relocation for employment.[114]

Hewitt announced a rule change as of the 1935–36 season, whereby any amateur player who wanted to try-out for a professional team could seek approval to do so by December 1, and could then return to amateur hockey providing that no contract was signed nor any money was received.[115]

In 1940, the CAHA changed its definition of an amateur to be, "any player not playing organized professional hockey".[116] Hewitt explained that the change prevented a professional club from using a player for a few games before returning him to amateur hockey, and that a professional player still needed to have one year's absence from organized hockey to be reinstated as an amateur.[116]

During World War II, Hewitt and the registration committee loosened player transfer and replacement rules when wartime enlistments led to player shortages.[117] CAHA president George Dudley defended the decision to reinstate former professionals as amateurs to prevent a shortage of player, despite it strengthening Royal Canadian Air Force teams compared to club teams.[118] After the war, Hewitt and the CAHA chose to allow discharged members of the Canadian Armed Forces to join any club in the CAHA, without requirement to meet existing residency or transfer rules.[119]

Hewitt acknowledged that money had changed hands when players were released from one branch to another, and believed that a club who spent money to develop a player was entitled to some remuneration such as a transfer fee. After the war, he and the CAHA discussed implementing a draft system for compulsory payments to release a player. He argued that a plan would be imminent, and that it would prevent arguments when players changed teams.[120]

Allan Cup competition

In November 1926, Allan Cup trustee William Northey suggested that the trophy be withdrawn unless the teams competing for it followed the amateur code more strictly. Hewitt felt that the sole point of contention was the travel allowance given by the CAHA, to teams travelling to play in Allan Cup games. The CAHA sought a new financial deal with the trustees, since it was financially dependent on the proceeds from Allan Cup gate receipts.[121] H. Montagu Allan agreed to donate the Allan Cup outright to the CAHA, and control of the Allan Cup along with a surplus of $20,700, was formally transferred to the CAHA in a ceremony at the Château Laurier on March 26, 1928.[122] Hewitt was subsequently named a trustee of the Allan Cup in 1929.[99]

Professional-amateur agreements

Hewitt and CAHA past-president W. A. Fry attended the 1930 National Hockey League (NHL) general meeting to seek a better working agreement. The CAHA suggested that players remain as amateurs for one season after graduating from junior hockey, and in return the CAHA would permit its amateurs to tryout and practice with professional teams.[123] Hewitt subsequently met multiple times with NHL president Frank Calder, who saw merit in Hewitt's request to keep players in amateur hockey, and continued to discuss a professional-amateur agreement.[124]

The NHL terminated the professional-amateur agreement in 1938, when a player suspended from the NHL was allowed to register as an amateur in Ottawa. Hewitt sat on the committee to reach a new agreement.[125] The CAHA agreed to decline overseas transfers for players on NHL reserve lists, and the NHL agreed not to sign junior-aged players without consent. Both bodies agreed to use the same playing rules, and recognized each other's suspensions.[126]

In 1942, Hewitt met with NHL to seek financial compensation on behalf of teams in Ontario, for the loss of amateur players who turned professional.[127] The CAHA agreed to defer the NHL's development payments to amateur teams, until the players lost to wartime enlistments had returned to professional hockey.[128] The professional-amateur agreement was renegotiated and the NHL agreed to pay a flat rate of $500 to the CAHA.[129]

Hewitt was part of the negotiating committee in 1952, where the CAHA and NHL agreed to a January 15 deadline for professional teams to call up players from the CAHA's Major Series of senior hockey. The agreement gave the NHL a source of emergency replacement players, and prevented teams in Canada from losing players during the Alexander Cup playoffs.[130]

In 1953, the NHL terminated the professional-amateur agreement when it the CAHA restricted the movement of junior-aged players from Western Canada to NHL-sponsored teams in Eastern Canada.[131] Junior teams in Western Canada wanted to keep their best players and sought greater financial compensation. Hewitt participated in negotiations to reach a new agreement in 1954, and felt that having an agreement with the professionals was "the greatest thing this organization has ever had", and that it would be "a crime" to lose it.[132] The CAHA agreed to distribute playoffs proceeds proportional to the profit on a series-by-series basis, but rejected the request for transfers from west to east.[133]

International relations

The CAHA cancelled its alliance with the USAHA in 1925, after Hewitt had three months of unsuccessful negotiations regarding of player transfers.[97] The USAHA subsequently disbanded following the 1924–25 season.[134] The CAHA resumed international playoffs for senior hockey when Hewitt arranged a season between the 1934 Allan Cup champion Moncton Hawks and the Detroit White Stars.[135] He then travelled to the United States to locate the Hamilton B. Wills Trophy that had not been competed for since 1925. He believed the trophy to be in the possession of William S. Haddock, who was president of the USAHA when it folded.[136]

The Great Britain national men's team defeated Canada and won the gold medal in ice hockey at the 1936 Winter Olympics, in which Jimmy Foster and Alex Archer played for Great Britain while under suspension by the CAHA.[137] The relationship between the CAHA and the British Ice Hockey Association (BIHA) deteriorated, and the CAHA banned all of its players from applying for transfers to Great Britain until an agreement was reached. Hewitt was part of the committee to negotiate peace with the BIHA.[138] A new agreement was announced on June 27, 1936, where the BIHA agreed to the CAHA approving player transfers, and that all players suspended by the CAHA would not play in Great Britain.[139]

In April 1937, Hewitt arranged an international tournament hosted in Toronto among the Allan Cup and Memorial Cup champions of the CAHA, the Eastern Amateur Hockey League (EAHL) and the English National League. The tournament coincided with national teams playing at the 1937 Ice Hockey World Championships held at the same time in England.[140] The world's amateur club team title was contested by the Wembley Lions, the Hershey Bears, the Sudbury Tigers, and the Winnipeg Monarchs.[141] In August 1937, Hewitt was part of a CAHA delegation which reached a working agreement with the EAHL that ended wholesale roster moves from Canada to the United States, and allowed for one player per Canadian team to be imported to the league with additional transfers possible if approved by the CAHA.[142]

The CAHA and the Amateur Hockey Association of the United States collaborated to establish the International Ice Hockey Association in 1940, as a governing body for international hockey due to inactivity of the Ligue Internationale de Hockey sur Glace (LIHG) during World War II.[143] Hewitt served as one of the CAHA delegates to meetings of the International Ice Hockey Association.[144]

Playing rules committee

In 1923, Hewitt sought to standardize the weight of the hockey puck since nothing was mentioned in the playing rules of hockey at the time. He met with rubber manufacturers and had 11 different types of pucks tested and weighed, before a rule was implemented for a puck to weigh 5.5–6 ounces (160–170 g).[145] The CAHA appointed Hewitt to its rules committee in 1924, with the intent of standardizing the rules across Canada, and to liaise with professional leagues.[94] He served as chairman of the CAHA rules committee until the 1950s, and negotiated to have common rules for amateur and professional leagues.[146]

At the 1925 CAHA general meeting, Hewitt reported on establishing uniform rules with professional leagues, and indicated that Frank Calder of the NHL, and E. L. Richardson of the Western Canada Hockey League were willing to co-operate, whereas Frank Patrick of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association showed no interest.[147] Later in the same year, the CAHA rules committee was empowered to align amateur rules with the professional rules. Rules changes included elimination of body checking in the centre ice area between the blue lines, limiting the number of substitutes from three to two, increasing the distance from the end of the rink to the blues lines 20–40 feet (6.1–12.2 m), and allowing goaltenders to throw the puck behind their net instead of having to skate away with it.[148]

Hewitt continued to meet with Frank Calder in the 1920s and 1930s to discuss uniform rules of play, and consistent ice rink markings and dimensions.[149] Calder and the NHL pushed for the CAHA to adopt the professional rules, which he felt were supported by spectators and increased tickets sales in the NHL.[124] In 1929, the CAHA gave referees more powers to penalize infractions and to deter abusive language. Hewitt supported a rule change which allowed a referee to give a three-minute penalty to a player throwing a stick to prevent a goal-scoring opportunity.[150] In 1932, Hewitt toured Western Canada attending referee schools to have uniform interpretation of the rules of play.[151]

In 1938, Hewitt and the NHL agreed to implement a delay of game penalty for players holding the puck against the boards unless being challenged by an opposing player, and to widen the blue lines to reduce the number of offside infractions.[152] In 1941, the CAHA permitted its member associations to choose between utilizing a system with two referees and no linesmen during a game, or to have a three-official system with one referee and two linesmen.[153]

In 1943, the NHL agreed to a recommendation by the CAHA rules committee to implement a centre ice red line, to allow for longer passes by the defensive team without being ruled offside.[106][154] The change allowed the defending team to pass the puck to out of their own zone up to the red line, instead of being required to skate over the nearest blue line then pass the puck forward.[155]

The CAHA dissolved its rules committee in 1945, then resumed it in 1946 with Hewitt as chairman.[156] In 1947, the committee adopted the NHL's rules for offside and icing in 1947.[157] In 1948, Hewitt represented the CAHA in joint meetings with the NHL, the American Hockey League, and the United States Hockey League, to standardize playing rules in amateur hockey and multiple tiers of professional hockey.[158] In 1954, Hewitt favoured tightening the interpretation of rules by on-ice officials as a means to deter elbowing, high-sticking and boarding infractions.[159] He was named honorary chairman of the CAHA rules committee in 1959.[160]

Hockey's history and hall of fame

In 1941, the CAHA appointed a committee to write a history of hockey in Canada, led by James T. Sutherland, including Hewitt and Quebec hockey executive George Slater.[153][161] In 1943, the committee concluded that hockey had been played in Canada since 1855, and that Kingston and Halifax had equal claims to be the birthplace of hockey, since both cities hosted games played by the Royal Canadian Rifle Regiment. The report also stated that Kingston had the first recognized hockey league in 1885, which merged into the OHA in 1890.[162] A delegation from Kingston then went to the CAHA general meeting in 1943, and was endorsed to establish a Hockey Hall of Fame in Kingston.[161]

In September 1943, Hewitt was named to the board of directors for selecting inductees into the Hockey Hall of Fame, and sought recommendations by sportswriters from The Canadian Press and the Associated Press.[163] He was named chairman and secretary of the board of governors in 1944,[164] and the CAHA agreed to donate 25 per cent of its profits from the 1945–46 season to help erect a building for the hall of fame.[165] In May 1945, Hewitt announced that nine players were the first group of inductees into the Hockey Hall of Fame.[166] In October 1945, a special committee chosen by the board of governors named six "builders of hockey" to be added to the inaugural group of inductees.[167]

The Hockey Hall of Fame committee was incorporated in 1948, and elected an additional seven to its board of governors to give representation to a broader area.[168] Hewitt remained on the board of governors until 1950.[169] By September 1955, a building for the hall of fame had not been constructed in Kingston, when a group of businessmen from Toronto were given approval for a hall of fame building which opened at Exhibition Place in Toronto in 1961. A separate International Hockey Hall of Fame later opened in Kingston in 1965.[161]

Later years and retirement

Hewitt accompanied the Winnipeg Maroons as the CAHA representative on an exhibition tour of Czechoslovakia from December 1960 to January 1961.[170][171] He retired as the registrar-treasurer at age 86 on May 23, 1961,[9] and was succeeded by Gordon Juckes.[172]

On May 18, 1964, Hewitt cut the ceremonial ribbon at the Hockey Hall of Fame, to unveil CAHA plaques which commemorated the association's 50th anniversary.[173]

Remove ads

Olympics and athletics executive

Summarize

Perspective

During World War I, Hewitt served on the executive of the Sportsmen's Patriotic Association, which sought to provide sporting equipment to soldiers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force.[174] After the war, he sat on the AAU of C committee for the postwar reconstruction of sports.[175]

1920 Summer Olympics

The CAHA chose the Winnipeg Falcons as the 1920 Allan Cup champions to represent the Canada men's national team in ice hockey at the 1920 Summer Olympics, instead of forming a national all-star team on short notice.[176][35] Hewitt represented the Canadian Olympic Committee and oversaw finances for the Falcons, and reported on the Olympic Games for Canadian newspapers.[177][178] He and his wife were a father and mother figure to the Falcons,[179] and sailed with them aboard SS Melita from Saint John to Liverpool, then onto Antwerp.[176]

Hewitt introduced the CAHA rules of play to the LIHG at the Olympics.[180] Writer Andrew Podnieks described Hewitt's interpretation of the rules as "competitive yet gentlemanly", and that the rules of play were accepted for Olympic hockey.[181] Hewitt refereed the first game played in the history of ice hockey at the Olympic Games, an 8–0 win by the Sweden men's national team versus the Belgium men's national team, on April 23, 1920.[182] Hewitt felt that the Sweden team was physically rough by Canadian standards, since they knocked down the opposing player before taking the puck. After he stopped the game and asked if anyone on the team spoke English, the goaltender for Sweden briefly spoke with Hewitt then conferred with his teammates, but they did not understand Hewitt's instructions on the Canadian style of play.[183] The Falcons and the Hewitts returned home aboard SS Grampian from Le Havre to Quebec City.[184] The Falcons honoured Hewitt and his wife at a private dinner and presented them with a silver cup inscribed with the number 13, for the number of people who made the trip to the Olympics and the team's lucky number.[35][185]

The Canadian Olympic Committee named Hewitt to its sub-committee for boxing to select who represented Canada at the 1920 Summer Olympics,[186] and had been credited with officiating hundreds of bouts as a boxing referee in Toronto.[2] He oversaw travel arrangements for the national team to the remainder of the 1920 Summer Olympics which began in August.[187] The boxers which he helped select won one gold, two silver, and two bronze medals for Canada.[188]

1924 Winter Olympics

Hewitt was appointed to the Canadian Olympic Committee in 1923, by its president Patrick J. Mulqueen to represent the CAHA.[189] The CAHA chose the Toronto Granites as the 1923 Allan Cup champions to represent Canada in ice hockey at the 1924 Winter Olympics, and Hewitt was again chosen oversee the national team's finances at the Olympics.[190][191] Hewitt was empowered by the CAHA to name replacement players as needed,[192] and recruited Harold McMunn and Cyril Slater as replacements when four players from the Granites were unable to travel to the Olympics.[193]

The Granites and Hewitt sailed from Saint John, aboard SS Montcalm to Liverpool, then travelled to Chamonix.[194] In his weekly report to the Toronto Daily Star, Hewitt wrote that the Granites would face multiple changes in conditions compared to hockey games in Canada. He did not feel the team would be affected by playing outdoors on natural ice in the morning or afternoon, despite that the team was accustomed to playing indoors with electric lighting on artificial ice. He also felt that the larger ice surface and lack of boards around the sides of the rink would mean more stick handling and less physical play.[195]

During the Olympics, Hewitt attended the annual meeting and elections for the LIHG. Since its rules stated that one of the vice-presidents must be from North America, Hewitt and USAHA president William S. Haddock opted for a coin toss, which decided that Haddock was elected to the position.[196] When the Olympics organizers wanted to select hockey referees by drawing names out of a hat, Hewitt and Haddock agreed to another coin toss to decide on the referee for the game between Canada and the United States men's national team. Hewitt feared having an inexperienced referee for the game, and his suggested to have LIHG president Paul Loicq officiate the game was confirmed by the coin toss.[197] The Granites defeated the United States team by a 6–1 score, and won all six games played to be the Olympic gold medallists.[198] After the Olympics, Hewitt accompanied the Granites to exhibition games in Paris and London, followed by an audience with HRH The Prince of Wales at St James's Palace, then sailing to Canada aboard SS Metagama from Liverpool to Saint John.[199]

1924 to 1928

Hewitt was renamed to the boxing committee for Canada at the 1924 Summer Olympics,[200] where Canadian boxers won a bronze medal.[201] He served as chairman of the AAU of C registration committee for 1926 and 1927. The committee was opposed to professionals and amateurs playing within the same league, and he oversaw the reinstatement of professionals as amateurs.[202] He was appointed to the AAU of C affiliations and alliances committee for 1927 and 1928,[203] which sought to have the CRU as an affiliated member and to promote amateur sport in Canada.[204] He also discussed an AAU of C alliance with the Dominion Football Association, which failed due to disagreements on the mingling of amateurs and professionals in soccer.[205] He later represented the Canadian Olympic Committee at the annual meeting for the Women's Amateur Athletic Federation of Canada in 1927.[206]

1928 Winter Olympics

The Canadian Olympic Committee appointed Hewitt as head of mission for Canada at the 1928 Winter Olympics. He oversaw travel arrangements for the delegation which included figure skating, speed skating, skiing, and ice hockey.[207] Hewitt and the Canadian delegation totalled 47 people, and sailed from Halifax aboard SS Arabic to Cherbourg, then travelled to St. Moritz.[208]

The University of Toronto Graduates as the 1927 Allan Cup champions were chosen to represent Canada in ice hockey, and Hewitt oversaw the team's finances at the Olympics. Conn Smythe coached the team during the OHA season, but refused to go to the Olympics due to disagreements on which players were added to the team by the Canadian Olympic Committee. The Graduates went without Smythe, led by team captain Red Porter.[208]

Hewitt was opposed to the format of the hockey tournament at the Olympics, which saw the Canadian team receive a bye into the second round. He wanted the team to have more games, rather than be idle for a week.[209] Despite the wait to play, the Graduates won all three games by scoring 38 goals and conceding none, to win the gold medal. After an exhibition tour through Austria, Germany, France and England, Hewitt and the Graduates returned to Canada aboard SS Celtic.[210]

Later involvement

Hewitt served on the executive of the Canadian Olympic Committee which selected athletes to compete at the 1928 Summer Olympics.[211] In 1930, he was the chairman of the AAU of C publicity committee.[212] He served as chairman of the winter games sub-committee of the Canadian Olympic Committee, which selected the Winnipeg Hockey Club as the 1931 Allan Cup champions, to represent Canada in ice hockey at the 1932 Winter Olympics. The Canadian Olympic Committee chose Claude C. Robinson to oversee finances for the team, while Hewitt was named honorary manager of the Winnipeg Hockey Club which won the gold medal at the Olympics. Hewitt sought for future Canadian national teams at the Olympics to be the reigning Allan Cup champion team, strengthened with six additional players.[213] He remained on the Canadian Olympic Committee executive to select athletes for the 1932 Summer Olympics.[214]

Remove ads

Football career

Summarize

Perspective

Hewitt was a football referee in the early 1900s, after he played with the Toronto Football Club and the Toronto Wellesleys. He transitioned into managing football and was able to recruit players whom he had become familiar with as a referee.[215] He was an executive with Toronto Football Club, and represented the team in meetings of the Ontario Rugby Football Union (ORFU) in 1902.[216] He became the manager of the team in 1904.[2] He led the team to two wins and two losses during the 1904 season, but were defeated in two consecutive games by the Hamilton Tigers in the ORFU championship.[217]

When the Toronto Football Club merged with the Toronto Argonauts in 1905, Hewitt served as manager of the Argonauts until 1907.[2] In the 1905 season, he led the team to two wins, two losses, and second place in the ORFU,[218] then were defeated in the ORFU championship by the Hamilton Tigers.[219] He led the Argonauts to four wins, two losses, and second place in ORFU for the 1906 season,[220] but did not qualify for the playoffs.[221]

Hewitt was vice-president of the ORFU for the 1905 and 1906 seasons,[222][223] and represented the Argonauts at ORFU meetings.[224] He sought for ORFU to have uniform rules of play with the Canadian Rugby Union (CRU), with a preference to use the snap-back system of play used in Ontario.[225] When the CRU did not adopt the snap-back system, his motion was approved for the ORFU to adopt the CRU rules in 1906.[226]

In December 1906, The Gazette reported that a proposal originated from Ottawa for the ORFU and the Quebec Rugby Football Union to merge, which would allow for higher calibre of play and create rivalries.[223] Hewitt and the Argonauts favoured the higher-level league, and sought for all players to have unquestioned amateur status.[227] He helped organize the meeting which established the Inter-provincial Rugby Football Union (IRFU) in 1907, which included teams from Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto and Hamilton.[2][15] In the 1907 season, his team won just once in six games and did not qualify for the IRFU playoffs.[228]

Hewitt continued to serve on the ORFU executive, was named a delegate to the CRU meetings in 1911.[229] and was elected secretary of the ORFU in 1913.[230] He was named to the CRU executive in 1912, and helped arrange matches for the senior and junior national championships.[231] He was elected first vice-president of the CRU in 1914, which coincided with annual discussions dealing with rules changes due to the influence American football.[232]

The CRU elected Hewitt president for the 1915 season. He appointed a commission to establish uniforms rules of play at different levels including collegiate and senior.[233] He approached multiple football coaches and sought feedback on best ways to implement standard playing rules.[234] After the CRU did not operate from 1916 to 1918 due to World War I,[235] Hewitt returned as president for the 1919 season.[3][11] Due to disagreements on playing rules in Western Canada, lack of interest in Eastern Canada, and students prioritizing studies instead of intercollegiate sports; national playoffs were not held in 1919.[235]

Hewitt later served as a referee for collegiate and IRFU games c. 1919 – c. 1923,[236][237] and represented referees on the CRU commission to revise and standardize the rules of play.[238]

Remove ads

Horse racing official

Summarize

Perspective

While reporting on horse racing, Hewitt made frequent visits to Ontario Jockey Club secretary W. P. Fraser, who appointed him patrol judge at Woodbine Race Course in 1905. Hewitt became steward at the Thorncliffe Park Raceway in 1917, then later at the Devonshire Raceway and Kenilworth Park Racetrack in Windsor, and at Stamford Park in Niagara Falls.[239] Hewitt and his son Foster called the first horse race broadcast on radio, the King's Plate in 1925.[35] Hewitt was a steward of the Incorporated Canadian Racing Association for 31 years,[1][240] and was named the chief steward in 1937, after many years as the assistant steward.[2][79]

On June 5, 1937, Hewitt was one of the stewards which ordered a rerun at Thorncliffe Park Raceway, after the race was declared a false start when one horse was missing from its stall and the flag had not been dropped when other horses jumped the barrier. The decision was protested by spectators who stood to lose bets placed on the race, and an angry mob occupied the track for more than two hours in a near-riotous protest.[241]

In 1938, the Incorporated Canadian Racing Association debated actions to take regarding doping in horses.[242] As a steward, he imposed the suspension of trainer and a horse, due to tests on the saliva of a horse.[243]

When the Government of Canada imposed a 5 per cent tax for betting on horse racing in 1941, Hewitt felt it would not affect wagers, and was among a group which pledged that race tracks would co-operate with the government.[244]

In 1950, the Legislative Assembly of Ontario passed a bill to establish a body to oversee all forms of horse racing in the province, and to issue licenses to all persons involved in the sport. Hewitt was recommended to be on its governing committee by member of parliament, William Houck.[245] The Ontario Racing Association was established in April 1950, and appointed Hewitt as steward.[246] He subsequently served 14 years in the position.[11] He was involved in the investigation and discipline of jockeys and trainers, reforms to riding fees paid to jockeys, establishing medical examination requirements for jockeys and horses, and the implementation of recording races on film to investigate a close finish or foul play during the race.[247]

Remove ads

Personal life

Summarize

Perspective

Hewitt lived on Roxborough Street at Yonge Street in the Rosedale neighbourhood of Toronto, and had a summer house on the Toronto Islands in proximity to Hanlan's Point Stadium.[8][248] On Sundays, he regularly took the family on road trips in their 1912 Pullman automobile to Hamilton or Oakville, and his children sometimes accompanied him in the press box while he reported on sporting events.[8] While on family vacation, Hewitt and his son attended the 1918 World Series in Boston, and were later stricken with the 1918 influenza pandemic.[249] Hewitt's grandson Bill Hewitt (born 1928) followed in the family footsteps with a career as a sports commentator.[1][3][9]

In June 1948, Hewitt recovered from a three-month skin ailment which doctors thought would affect his heart and end his sporting career.[250] On November 15, 1952, his wife was killed in a head-on automobile collision on U.S. Route 6 east of Scranton, Pennsylvania. The vehicle driven by his son-in-law, Charles A. Massey, skidded on a curve and hit an oncoming car.[251][252] Hewitt had both of his arms broken in the accident.[1]

Hewitt published his memoirs in 1958, titled Down the Stretch: Recollections of a Pioneer Sportsman and Journalist.[253][254]

While boarding a plane with the Winnipeg Maroons in Prague, he had an asthmatic heart attack and was taken to hospital. He had pneumonia at the time and a previous heart condition.[170] He was transferred to The London Clinic in England on January 19,[171] where he recovered and returned to Canada on January 27.[255] He later joked that his best memory of the incident was that Elizabeth Taylor later took over his suite in the London hospital.[9]

Hewitt was frail in later life, lived with his son Foster, and then at a retirement home in Toronto.[256] Hewitt died on September 8, 1966, in Toronto.[1][3][11] He was interred with his wife in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, Toronto, plot 3, lot 7.[257][258] He left an estate valued at CA$136,262, equivalent to $1,223,243 in 2023, which included shares in the Toronto Granite Club.[259]

Remove ads

Honours and awards

Summarize

Perspective

Hewitt was made a life member of the OHA on December 5, 1925.[50][79][260] In 1938, he was a guest of honour at an Ontario Sportsmen's Association banquet, and was given a silver cup in recognition of his 35 years of work with the OHA.[261] At the OHA's golden jubilee in 1939, he was honoured for his work as secretary which helped the association reach its milestone.[262]

In October 1945, Hewitt was chosen for induction into the Hockey Hall of Fame, among the six original members of the builder category.[167] The Hockey Hall of Fame and the International Hockey Hall of Fame both list his year of induction as 1947.[50][263] At the 1948 CAHA general meeting, Hewitt was presented with a scroll from the Hockey Hall of Fame in recognition of his induction.[264]

Hewitt received the OHA Gold Stick Award in 1947, and was among the inaugural group recognized by the highest award given by the OHA for contributions to hockey.[265] He received a citation from Tommy Lockhart of the Amateur Hockey Association of the United States in 1950, for service to hockey in the USA where he assisted with setting up amateur leagues.[266] On December 8, 1953, Hewitt was the guest of honour at a testimonial dinner attended by 500 sportsmen from Canada and the United States, to celebrate his 50th anniversary as secretary of the OHA.[2][15] In 1955, the OHA established an endowment at the Hospital for Sick Children, with a bed named Hewitt and his wife.[267]

At the general meeting in 1960, Hewitt was made a life member of the CAHA.[268] He was given a standing ovation when he retired at the general meeting in 1961, and the CAHA stated it would later present Hewitt with a painting of his choice.[9] In 1966, Hewitt was the guest of honour at a second testimonial dinner to recognize his OHA career, when he was named honorary life secretary of the OHA.[256] In May 1966, he received a sports citation from the Government of Ontario in recognition of his sporting career.[269]

Hewitt was posthumously recognized by the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) for contributions to the international game with induction into the builder category of the IIHF Hall of Fame in 1998.[270]

Remove ads

Legacy and reputation

Summarize

Perspective

Hewitt had multiple ice hockey trophies named for him, including the W. A. Hewitt Trophy for the winner of the playoffs series between the senior A-level champions of the OHA and the Northern Ontario Hockey Association,[271] the W. A. Hewitt Trophy awarded to the senior B-level champion of the OHA,[272] and the W. A. Hewitt Trophy awarded to the bantam B-level finalists in the Ontario Minor Hockey Association.[273] Hewitt and George Dudley are the namesakes of the Dudley Hewitt Cup. It was first awarded by the Canadian Junior Hockey League in 1971, to the Central Canada Junior A champion team who moves on to the national Centennial Cup competition.[274][275][276]

The origins of hockey committee reported that the first nets on hockey goalposts were introduced during a game in Montreal by Hewitt, who was then the sporting editor of the Montreal Herald. In the same report, Hewitt stated that the idea came from fellow journalist Francis Nelson, who conceived the nets while on a visit to Australia. Hewitt also stated that nets might have been used in the OHA sooner than in Montreal.[277] Despite Hewitt giving credit to Nelson, reports persisted that credited Hewitt with introducing nets, including his obituary in The Toronto Daily Star.[35][50][193]

James T. Sutherland stated that the OHA was fortunate to have Hewitt as its secretary, and "owe[d] most of its success" to him.[278] Sutherland referred to Hewitt as a "miracle man of hockey who [did] more than anyone to guide the game through its scant and lean years".[79] Journalist Scott Young credited Hewitt for being a forward thinker, and in tune with George Dudley in reversing the ban on professional coaches in the OHA.[279]

The Kingston Whig-Standard columnist Mike Rodden wrote that Hewitt was, "a solid man who followed a chosen star of destiny" as an ice hockey executive, and "a kindly man but he was so dedicated to the cause that he tolerated no nonsense".[193] The Canadian Press writer Wilfred Gruson described Hewitt as, "one of the most respected authorities in the Dominion on hockey and horse racing", and that Hewitt was unequalled "in his knowledge of the complexities of [hockey]".[250] The Canadian Press sports editor Jack Sullivan wrote, "most almost to a fault, [Hewitt] had remained behind the scenes in various administrative capacities while nursing these sports to their present status".[15]

Remove ads

Notes

- Hewitt wrote in his memoirs that he guarded his middle name as a secret, and that his namesake was parliamentarian and educator Abraham Code.[10]

- The Miller Act was named for Henry Morton Miller, the member of parliament for Grey South, who introduced to legislation regulate gambling in horse racing.[45]

Remove ads

References

Sources

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads