Vladimir Menshov

Soviet and Russian actor and director (1939–2021) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Vladimir Valentinovich Menshov (Russian: Влади́мир Валенти́нович Меньшо́в; 17 September 1939 – 5 July 2021)[1] was a Soviet and Russian actor and film director.[2][3] He was noted for depicting the Russian everyman and working class life in his films. Although Menshov mostly worked as an actor, he is better known for the films he directed, especially for the 1979 melodrama Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears, which won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.[4][5] Actress Vera Alentova, who starred in the film, is the mother of Vladimir Menshov's daughter Yuliya Menshova.[6]

Vladimir Menshov | |

|---|---|

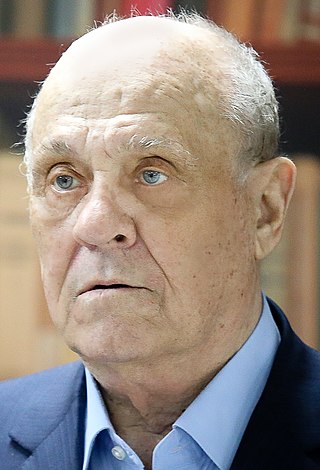

Menshov in 2018 | |

| Born | Vladimir Valentinovich Menshov 17 September 1939 |

| Died | 5 July 2021 (aged 81) Moscow, Russia |

| Nationality | Russian, Azerbaijani |

| Education | Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography |

| Occupation(s) | Actor, director, screenwriter, producer |

| Notable work |

|

| Spouse | Vera Alentova |

| Children | Yuliya Menshova |

| Awards |

|

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Menshov was born in a Russian family in Baku, Azerbaijan SSR.[7] His father, Valentin Mikhailovich Menshov, was a sailor and later an NKVD officer; his mother Antonina Aleksandrovna Menshova (née Dubovskaya) was a housewife. Because of his father's work, the family lived in Baku, Arkhangelsk and Astrakhan.[8]

As a teenager Menshov worked as a machinist student at a factory, at a mine in Vorkuta, as a sailor on a diving boat in Baku, and also as an understudying actor at the Astrakhan Drama Theater.[9] In 1961 he entered the acting department of the Moscow Art Theatre School. During the second year he married actress Vera Alentova who was also studying at the same theatre school.[10] In 1965 he graduated from the acting department.[11] After graduating, he worked for two years as actor and assistant director at the Stavropol Regional Drama Theater.[9]

In 1970 he graduated from the VGIK postgraduate course in the department of feature film direction[11] (Mikhail Romm's workshop).[12]

From 1970 to 1976, Vladimir Menshov worked under contracts at the film studios Mosfilm, Lenfilm and the Odessa Film Studio.[13] He made a short thesis film On the Question of the Dialectic of the Perception of Art, or Lost Dreams,[14] wrote the stage version of the novel Mess-Mend by Marietta Shaginyan, which was staged at the Leningrad Youth Theater,[15] and wrote the script I'm Serving on the Border at the request of Lenfilm.[2]

In those years his cinematic acting career began: he starred in the title role in the thesis work of his classmate Alexander Pavlovsky Happy Kukushkin.[13] The film was shot at the Odessa Film Studio.[16] Vladimir Menshov also was a co-author of the script. The picture received the main prize at the Molodist-71 Kiev Film Festival[17][16] Menshov starred in a 1972 film by Alexei Sakharov called A Man in His Place.[15] In 1973 Menshov was awarded the first prize for the best performance at the VI All-Union Film Festival in Almaty.[18][19]

As an actor, Vladimir Menshov has 117 credits. Some of the most popular films that feature him include How Czar Peter the Great Married Off His Moor (1976),[16] Where is the Nophelet? (1987),[20] Night Watch (2004), Day Watch (2006) and Legend № 17 (2013).[21]

Menshov's directorial debut took place in 1976, it was the film Practical Joke.[22] Menshov's second picture, Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears became one of Russia's box-office record holders, was awarded the State Prize of the USSR, and then the Oscar (1981) as the Best Foreign Language Film.[23] The film tells the story of lives of three women over two decades. It was also a box-office hit.[24]

In 1984, Menchov directed the film Love and Pigeons based on the play of Vladimir Gurkin.[25]

Vladimir Menshov also directed the following films: What a Mess! (1995),[22] The Envy of Gods (2000), and The Great Waltz.[13] The Great Waltz was not finished.[26]

He wrote screenplays for the films I Serve on the Border (1973), The Night Is Short (1981), What a Mess! (1995), The Great Waltz (2008),[13] was the producer of several films, among which: Love of Evil (1998), Chinese Service (1999), Quadrille (1999), The Envy of Gods (2000), Neighbor (2004), A Time to Gather Stones (2005), Shawls (2006), and The Great Waltz.[9]

In 2004, Menshov was the host of the Channel One show Last Hero.[27]

Vladimir Menshov was the general director and art director of "Film Studio Genre", which is a subsidiary of Mosfilm.[14]

In 2011 as the chair of the Russian Academy Award committee he refused to co-sign the decision to nominate Nikita Mikhalkov's film Burnt by the Sun 3: The Citadel as the Russian submission for the 2011 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.[28]

He expressed support for the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation[29] and was blacklisted in Ukraine in 2015 as a result.[30]

Awards

Summarize

Perspective

Vladimir Menshov – Honored Artist of the RSFSR (1984),[14] People's Artist of Russia (1989),[22] winner of the State Prizes of the RSFSR (1978,[22] for the film Rally) and the USSR (1981,[22] for the film Moscow Does not Believe in Tears).

- The Order of Merit for the Fatherland, IV degree (1999)[14]

- The "For Services to Moscow" badge (30 July 2009)[2]

- The Order of Merit for the Fatherland, III degree (2010)[14]

- The Golden Eagle Award as Best Supporting Actor in Legend No. 17 (2014)[31]

- The Order of Merit for the Fatherland, II degree (2017)[14]

Political views and career

At the elections to the State Duma in 1995, Menshov was included in the federal list Trade Unions, Industrialists of Russia, Labor Union. In 1999, he was a member of the presidium of the All Russia party. He ran for the post of vice-governor of the Moscow region together with Anatoly Dolgolaptev. In April 2001, he signed a letter in support of the recently elected Russian President Vladimir Putin's policy on Chechnya.[32][33]

In 2003, Menshov joined the United Russia party.[34] In an interview with Esquire magazine in 2010, he stated that he joined it by accident and regrets it and treats the party's activities with irony, but does not leave its ranks in order to avoid scandal.[35] However, in the 2016 legislative election, Menshov became a trusted representative of United Russia.[36]

In 2007, answering a question about a possible third term for Vladimir Putin's presidency, Menshov said that he was "sharply negative" about this scenario and criticized his colleagues who said there were no alternatives to the current head of state.[37] During the 2018 presidential election, Menshov became one of Putin's trusted representatives.[38][39] However, in 2016, Menshov claimed that he always voted for the communists[40] and positively assessed the Soviet Union.[41]

In 2011, Menshov gave an interview about his political views, where he stated: "Over the years, it has become completely clear to me: if you take the path of anti-Sovietism, you will certainly come to outright Russophobia."[42]

Menshov supported the annexation of Crimea by Russia[43] and expressed his opinion on the need for "reunification" with Donbass,[44] and gave Zakhar Prilepin 1 million rubles in aid "for Donbass." In 2017, the Security Service of Ukraine banned Menshov from entering the country for a period of 5 years.[45]

Menshov planned to run for the State Duma in the 2021 legislative election from the A Just Russia party on its federal party list.[46]

Personal life and death

Menshov married actress Vera Alentova in 1962. They had a daughter, Yuliya Menshova.

Partial filmography

As a director

| Year | Title | Notes | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | Practical Joke | [16] | |

| 1979 | Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears | [16] | |

| 1984 | Love and Pigeons | [16] | |

| 1995 | What a Mess! | [16] | |

| 2000 | The Envy of Gods | [48] | |

As an actor

| Year | Title | Role | Notes | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Happy Kukushkin | Pashka Kukushkin | Short film | [16] |

| 1972 | A Man at His Place | Semyon Bobrov | [15] | |

| 1976 | How Czar Peter the Great Married Off His Moor | Officer | [16] | |

| 1977 | Practical Joke | Vladimir Valentinovich | Uncredited role | [49] |

| 1982 | Under One Sky | Pavlov | ||

| 1983 | Magistral | Potappov | ||

| 1984 | Love and Pigeons | Cameo | Also directed | [50] |

| 1987 | Courier | Oleg Nikolaevich | [16][48] | |

| 1987 | Where is the Nophelet? | Pavel Golikov | [51] | |

| 1989 | Zerograd | Prosecutor | [15] | |

| 1991 | Abdullajon | Navlo Buchko | [52] | |

| 1992 | The General | Georgy Zhukov | [15] | |

| 1993 | In Order to Survive | Oleg | Also known under the title Red Mob | [53][54] |

| 1995 | What a Mess! | Russian President | [21] | |

| 1997 | Tsarevich Alexei | Menshikov | [48] | |

| 1999 | 8 ½ $ | Spartak | [55] | |

| 2002 | Spartacus and Kalashnikov | colonel Egorov | ||

| 2004 | Night Watch | Geser | [56] | |

| 2004 | Diversant | General of military intelligence Kalyazin | [16][21] | |

| 2006 | Day Watch | Geser | [56] | |

| 2007 | The Apocalypse Code | Kharitonov | [2] | |

| 2007 | Liquidation | Georgy Zhukov | Television miniseries | [57] |

| 2009 | O Lucky Man! | Oleg Genrikhovich | ||

| 2011 | Lucky Trouble | Tryokhgolovich | [56] | |

| 2011 | Generation P | Farseykin | [57] | |

| 2012 | Legend No. 17 | Eduard Balashov | [56][21] | |

| 2013 | Möbius | Cherkachin | [58] | |

| 2014 | Ekaterina | Bestuzhev | [56] | |

| 2016 | After You're Gone | Father | [59] | |

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.