Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Timeline of tuberous sclerosis

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The history of tuberous sclerosis (TSC) research spans less than 200 years. TSC is a rare, multi-system genetic disease that can cause benign tumours to grow on the brain or other vital organs such as the kidneys, heart, eyes, lungs, and skin. A combination of symptoms may include seizures, developmental delay, behavioural problems and skin abnormalities, as well as lung and kidney disease. TSC is caused by mutations on either of two genes, TSC1 and TSC2, which encode for the proteins hamartin and tuberin respectively. These proteins act as tumour growth suppressors and regulate cell proliferation and differentiation.[1] Originally regarded as a rare pathological curiosity, it is now an important focus of research into tumour formation and suppression.

The history of TSC research is commonly divided into four periods.[2] In the late 19th century, notable physicians working in European teaching hospitals first described the cortical and dermatological manifestations; these early researchers have been awarded with eponyms such as "Bourneville's disease"[3] and "Pringle's adenoma sebaceum".[4] At the start of the 20th century, these symptoms were recognised as belonging to a single medical condition. Further organ involvement was discovered, along with a realisation that the condition was highly variable in its severity. The late 20th century saw great improvements in cranial imaging techniques and the discovery of the two genes. Finally, the start of the 21st century saw the beginning of a molecular understanding of the illness, along with possible non-surgical therapeutic treatments.

Remove ads

19th century

- 1835

- French dermatologist Pierre François Olive Rayer published an atlas of skin diseases. It contains 22 large coloured plates with 400 figures presented in a systematic order. On page 20, fig. 1 is a drawing that is regarded as the earliest description of tuberous sclerosis.[5] Entitled "végétations vasculaires", Rayer noted these were "small vascular, of papulous appearance, widespread growths distributed on the nose and around the mouth".[6] No mention was made of any medical condition associated with the skin disorder.

- 1850

- English dermatologists Thomas Addison and William Gull described, in Guy's Hospital Reports, the case of a four-year-old girl with a "peculiar eruption extending across the nose and slightly affecting both cheeks", which they called "vitiligoidea tuberosa".[7]

- 1862

- German physician Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen, who was working as an assistant to Rudolf Virchow in the Institute for Pathological Anatomy in Berlin,[8] presented a case to the city's Obstetrical Society.[9] The heart of an infant who "died after taking a few breaths" had several tumours. He called these tumours "myomata", one of which was the "size of a pigeon's egg".[7] He also noted the brain had "a great number of scleroses".[5] These were almost certainly the cardiac rhabdomyomas and cortical tubers of tuberous sclerosis. He failed to recognise a distinct disease, regarding it as a pathological-anatomical curiosity.[10] Von Recklinghausen's name would instead become associated with neurofibromatosis after a classic paper in 1881.[8]

- 1864

- German pathologist Rudolf Virchow published a three-volume work on tumours that described a child with cerebral tuberous sclerosis and rhabdomyoma of the heart. His description contained the first hint that this may be an inherited disease: the child's sister had died of a cerebral tumour.[11]

- 1880

- French neurologist Désiré-Magloire Bourneville had a chance encounter with the disease that would bear his name. He was working as an unofficial assistant to Jean Martin Charcot at La Salpêtrière.[10] While substituting for his teacher, Louis J.F. Delasiauve,[12] he attended to Marie, a 15-year-old girl with psychomotor retardation, epilepsy and a "confluent vascular-papulous eruption of the nose, the cheeks and forehead". She had a history of seizures since infancy and was taken to the children's hospital aged three and declared a hopeless case. She had learning difficulties and could neither walk nor talk. While under Bourneville's care, Marie had an ever-increasing number of seizures, which came in clusters. She was treated with quinquina, bromide of camphor, amyl nitrite, and the application of leeches behind the ears. On 7 May 1879 Marie died in her hospital bed. The post-mortem examination disclosed hard, dense tubers in the cerebral convolutions, which Bourneville named Sclérose tubéreuse des circonvolutions cérébrales. He concluded they were the source (focus) of her seizures. In addition, whitish hard masses, one "the size of a walnut", were found in both kidneys.[13]

- 1881

- German physician Hartdegen described the case of a two-day-old baby who died in status epilepticus. Post-mortem examination revealed small tumours in the lateral ventricles of the brain and areas of cortical sclerosis, which he called "glioma gangliocellulare cerebri congenitum".[14][15]

- 1881

- Bourneville and Édouard Brissaud examined a four-year-old boy at La Bicêtre. As before, this patient had cortical tubers, epilepsy and learning difficulties. In addition he had a heart murmur and, on post-mortem examination, had tiny hard tumours in the ventricle walls in the brain (subependymal nodules) and small tumours in the kidneys (angiomyolipomas).[16]

- 1885

- French physicians Félix Balzer and Pierre Eugène Ménétrier reported a case of "adénomes sébacés de la face et du cuir" (adenoma of the sebaceous glands of the face and scalp).[17] The term has since proved to be incorrect as they are neither adenoma nor derived from sebaceous glands. The papular rash is now known as facial angiofibroma.[18]

- 1885

- French dermatologists François Henri Hallopeau and Émile Leredde published a case of adenoma sebaceum that was of a hard and fibrous nature. They first described the shagreen plaques and later would note an association between the facial rash and epilepsy.[7][19]

- 1890

- Scottish dermatologist John James Pringle, working in London, described a 25-year-old woman with subnormal intelligence, rough lesions on the arms and legs, and a papular facial rash. Pringle brought attention to five previous reports, two of which were unpublished.[20] Pringle's adenoma sebaceum would become a common eponym for the facial rash.

Remove ads

Early 20th century

- 1901

- Italian physician GB Pellizzi studied the pathology of the cerebral lesions. He noted their dysplastic nature, the cortical heterotopia and defective myelination. Pellizzi classified the tubers into type 1 (smooth surface) and type 2 (with central depressions).[21][22]

- 1903

- German physician Richard Kothe described periungual fibromas, which were later rediscovered by the Dutch physician Johannes Koenen in 1932 (known as Koenen's tumours).[23]

- 1906

- Australian neurologist Alfred Walter Campbell, working in England, considered the lesions in the brain, skin, heart and kidney to be caused by one disease. He also first described the pathology in the eye. His review of 20 reported cases led him to suggest a diagnostic triad of symptoms that is more commonly attributed to Vogt.[24]

- 1908

- German paediatric neurologist Heinrich Vogt established the diagnostic criteria for TSC, firmly associating the facial rash with the neurological consequences of the cortical tubers.[25][26] Vogt's triad of epilepsy, idiocy, and adenoma sebaceum held for 60 years until research by Manuel Gómez discovered that fewer than a third of patients with TSC had all three symptoms.[5]

- 1910

- J. Kirpicznick was first to recognise that TSC was a genetic condition. He described cases of identical and fraternal twins and also one family with three successive generations affected.[27]

- 1911

- Edward Sherlock, barrister-at-law and lecturer in biology, reported nine cases in his book on the "feeble-minded". He coined the term epiloia, a portmanteau of epilepsy and anoia (mindless).[28] The word is no longer widely used as a synonym for TSC. The geneticist Robert James Gorlin suggested in 1981 that it could be a useful acronym for epilepsy, low intelligence, and adenoma sebaceum.[29]

- 1913

- H. Berg is credited with first stating that TSC was a hereditary disorder, noting its transmission through two or three generations.[30]

- 1914

- P. Schuster described a patient with adenoma sebaceum and epilepsy but of normal intelligence.[7] This reduced phenotypic expression is called a forme fruste.[31]

- 1918

- French physician René Lutembacher published the first report of cystic lung disease in a patient with TSC. The 36-year-old woman died from bilateral pneumothoraces. Lutembacher believed the cysts and nodules to be metastases from a renal fibrosarcoma. This complication, which only affects women, is now known as lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM).[32][33]

- 1920

- Dutch ophthalmologist Jan van der Hoeve described the retinal hamartomas (phakoma). He grouped both TSC and neurofibromatosis together as "phakomatoses" (later called neurocutaneous syndromes).[34]

- 1924

- H. Marcus noted that characteristic features of TSC such as intracranial calcifications were visible on x-ray.[35]

Remove ads

Mid-20th century

- 1932

- MacDonald Critchley and Charles J.C. Earl studied 29 patients with TSC who were in mental institutions. They described behaviour—unusual hand movements, bizarre attitudes and repetitive movements (stereotypies)—that today would be recognised as autistic. However it would be 11 years before Leo Kanner suggested the term "autism". They also noticed the associated white spots on the skin (hypomelanic macules).[36]

- 1934

- N.J. Berkwitz and L.G. Rigler showed it was possible to diagnose tuberous sclerosis using pneumoencephalography to highlight non-calcified subependymal nodules. These resembled "the wax drippings of a burning candle" on the lateral ventricles.[37]

- 1942

- Sylvan E. Moolten proposed "the tuberous sclerosis complex", which is now the preferred name. This recognises the multi-organ nature of the disease. Moolten introduced three words to describe its pathology: "the basic lesion is hamartial, becoming in turn tumor-like (hamartoma) or truly neoplastic (hamartoblastoma)."[38]

- 1954

- Norwegian pathologist Reidar Eker bred a line of Wistar rats predisposed to renal adenomas. The Eker rat became an important model of dominantly inherited cancer.[39]

- 1966

- Phanor Perot and Bryce Weir pioneered surgical intervention for epilepsy in TSC. Of the seven patients who underwent cortical tuber resection, two became seizure-free. Prior to this, only four patients had ever been surgically treated for epilepsy in TSC.[40]

- 1967

- J.C. Lagos and Manuel Rodríguez Gómez reviewed 71 TSC cases and found that 38% of patients have normal intelligence.[14][41]

- 1971

- American geneticist Alfred Knudson developed his "two hit" hypothesis to explain the formation of retinoblastoma in both children and adults. The children had a congenital germline mutation which was combined with an early lifetime somatic mutation to cause a tumour. This model applies to many conditions involving tumour suppressor genes such as TSC.[42] In the 1980s, Knudson's studies on the Eker rat strengthened this hypothesis.[43]

- 1975

- Giuseppe Pampiglione and E. Pugh, in a letter to The Lancet, noted that up to 69% of patients presented with infantile spasms.[44]

- 1975

- Riemann first used ultrasound to examine TSC-affected kidneys in the case of a 35-year-old woman with chronic renal failure.[45]

Remove ads

Late 20th century

- 1976

- Cranial computed tomography (CT, invented 1972) proved to be an excellent tool for diagnosing cerebral neoplasms in children, including those found in tuberous sclerosis.[46]

- 1977

- Ann Mercy Hunt MBE and others found the Tuberous Sclerosis Association in the UK to provide self help and to fund research.[47]

- 1979

- Manuel Gómez published a monograph: "Tuberous Sclerosis" that remained the standard textbook for three editions over two decades. The book described the full clinical spectrum of TSC for the first time and established a new set of diagnostic criteria to replace the Vogt triad.[14][48]

- 1982

- Kenneth Arndt successfully treated facial angiofibroma with an argon laser.[49]

- 1983

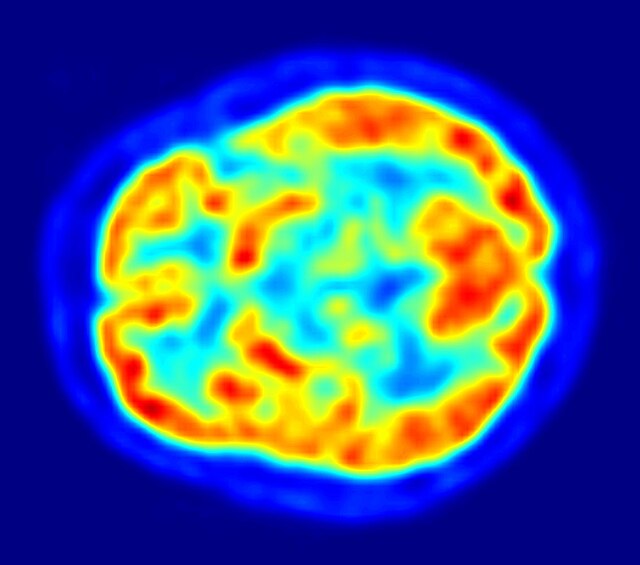

- Positron emission tomography (PET, invented 1981) was compared to electroencephalography (EEG) and CT. It was found to be capable of locating epileptogenic cortical tubers that would otherwise have been missed.[50]

- 1984

- The cluster of infantile spasms in TSC was discovered to be preceded by a focal EEG discharge.[51]

- 1985

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, invented 1980) was first used in TSC to identify affected regions in the brain of a girl with tuberous sclerosis.[52]

- 1987

- MR was judged superior to CT imaging for both sensitivity and specificity. In a study of fifteen patients, it identified subependymal nodules projecting into the lateral ventricles in twelve patients, distortion of the normal cortical architecture in ten patients (corresponding to cortical tubers), dilated ventricles in five patients, and distinguished a known astrocytoma from benign subependymal nodules in one patient.[53]

- 1987

- MR imaging was found to be capable of predicting the clinical severity of the disease (epilepsy and developmental delay). A study of 25 patients found a correlation with the number of cortical tubers identified. In contrast, CT was not a useful predictor, but was superior at identifying calcified lesions.[54]

- 1987

- Linkage analysis on 19 families with TSC located a probable gene on chromosome 9.[55]

- 1988

- Cortical tubers found on MR imaging corresponded exactly to the location of persistent EEG foci, in a study of six children with TSC. In particular, frontal cortical tubers were associated with more intractable seizures.[56]

- 1990

- Vigabatrin was found to be a highly effective antiepileptic treatment for infantile spasms, particularly in children with TSC.[57] Following the discovery in 1997 of severe persistent visual field constriction as a possible side-effect, vigabatrin monotherapy is now largely restricted to this patient group.[58]

- 1992

- Linkage analysis located a second gene to chromosome 16p13.3, close to the polycystic kidney disease type 1 (PKD1) gene.[59]

- 1993

- The European Chromosome 16 Tuberous Sclerosis Consortium announced the cloning of TSC2; its product is called tuberin.[60]

- 1994

- The Eker rat was discovered to be an animal model for tuberous sclerosis; it has a mutation in the rat-equivalent of the TSC2 gene.[61]

- 1995

- MRI with fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences was reported to be significantly better than standard T2-weighted images at highlighting small tubers, especially subcortical ones.[62][63]

- 1997

- The TSC1 Consortium announced the cloning of TSC1; its product is called hamartin.[64]

- 1997

- The PKD1 gene, which leads to autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), and the TSC2 gene were discovered to be adjacent on chromosome 16p13.3. A team based at the Institute of Medical Genetics in Wales studied 27 unrelated patients with TSC and renal cystic disease. They concluded that serious renal disease in those with TSC is usually due to contiguous gene deletions of TSC2 and PKD1. They also noted that the disease was different (earlier and more severe) than ADPKD and that patients with TSC1 did not suffer significant cystic disease.[65]

- 1997

- Patrick Bolton and Paul Griffiths examined 18 patients with TSC, half of whom had some form of autism. They found a strong association between tubers in the temporal lobes and the patients with autism.[66]

- 1998

- The Tuberous Sclerosis Consensus Conference issued revised diagnostic criteria.[67]

- 1998

- An Italian team used magnetoencephalography (MEG) to study three patients with TSC and partial epilepsy. Combined with MRI, they were able to study the association between tuberous areas of the brain, neuronal malfunctioning and epileptogenic areas.[68] Later studies would confirm that MEG is superior to EEG in identifying the eliptogenic tuber, which may be a candidate for surgical resection.[69]

Remove ads

21st century

Summarize

Perspective

- 2001

- A multi-centre cohort of 224 patients were examined for mutations and disease severity. Those with TSC1 were less severely affected than those with TSC2. They had fewer seizures and less mental impairment. Some symptoms of TSC were rare or absent in those with TSC1. A conclusion is that "both germline and somatic mutations appear to be less common in TSC1 than in TSC2".[70]

- 2002

- Several research groups investigated how the TSC1 and TSC2 gene products (tuberin and hamartin) work together to inhibit mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-mediated downstream signalling. This important pathway regulates cell proliferation and tumour suppression.[71]

- 2002

- Treatment with rapamycin (sirolimus) was found to shrink tumours in the Eker rat (TSC2)[72] and mouse (TSC1)[73] models of tuberous sclerosis.

- 2006

- Small trials showed promising results in the use of rapamycin to shrink angiomyolipoma[74] and astrocytomas.[75] Several larger multicentre clinical trials began: lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM)[76] and kidney angiomyolipoma (AML)[77] were treated with rapamycin; giant cell astrocytomas were treated with the rapamycin derivative everolimus.[78]

2012

A consensus conference was held and revised guidelines for the diagnosis and management of tuberous sclerosis were published.[79][80]

Remove ads

Notes

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads