Loading AI tools

1867-1868 novel by Émile Zola From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

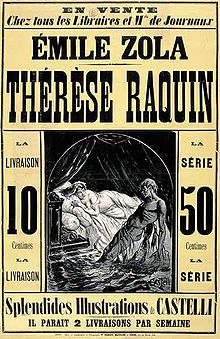

Thérèse Raquin [teʁɛz ʁakɛ̃] is an 1868 novel by French writer Émile Zola, first published in serial form in the literary magazine L'Artiste in 1867. It was Zola's third novel, though the first to earn wide fame. The novel's adultery and murder were considered scandalous and famously described as "putrid" in a review in the newspaper Le Figaro.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2013) |

Advertisement | |

| Author | Émile Zola |

|---|---|

| Original title | Thérèse Raquin |

| Translator | Edward Vizetelly Robin Buss |

| Language | French |

| Genre | Naturalism, theatrical naturalism, psychological novel |

| Set in | Paris, 1860s |

| Published | L'Artiste |

Publication date | 1867-68 (serialized) 1873 (as book) |

| Publication place | France |

Published in English | 1886–89[1] |

| Media type | Print: serialized in journal |

| Pages | 144 |

| 843.89 | |

| LC Class | PQ2521.T3 E5 |

| Preceded by | Les Mystères de Marseille |

| Followed by | Madeleine Férat |

Original text | Thérèse Raquin at French Wikisource |

Thérèse Raquin tells the story of a young woman, unhappily married to her first cousin by an overbearing aunt, who may seem to be well-intentioned but in many ways is deeply selfish. Thérèse's husband, Camille, is sickly and egocentric and when the opportunity arises, Thérèse enters into a turbulent and sordidly passionate affair with one of Camille's friends, Laurent.

In his preface, Zola explains that his goal in this novel was to "study temperaments and not characters".[2] Because of this detached and scientific approach, Thérèse Raquin is considered an example of naturalism.

Thérèse Raquin was first adapted for the stage as an 1873 play written by Zola himself. It has since then been adapted numerous times as films, TV mini-series, musicals, and an opera, among others.

Thérèse Raquin is the daughter of a French sea captain and an Algerian mother. After her mother's death, her father takes her to live with her aunt, Madame Raquin, and Camille, her valetudinarian son. Because her son is "so ill", Madame Raquin dotes on him to the point of spoiling him, and he is very selfish. Camille and Thérèse grow up side-by-side and Madame Raquin marries them to each other when Thérèse turns 21. Shortly thereafter, Camille decides that the family should move to Paris so he can pursue a career.

Thérèse and Madame Raquin set up shop in the Passage du Pont Neuf to support Camille while he searches for a job. He eventually starts working for the Orléans Railway Company, where he runs into a childhood friend, Laurent. Laurent visits the Raquins and, while painting a portrait of Camille, contemplates an affair with the lonely Thérèse, mostly because he cannot afford prostitutes anymore.

It soon becomes a torrid love affair. They meet regularly and secretly in Thérèse's room. After some time, Laurent's boss no longer allows him to leave early, so the lovers must think of something new. Thérèse comes up with the idea of killing Camille, and they become infatuated with the idea of being able to be together permanently while being married. It seems Camille is the only obstacle in this. They eventually drown him during a boat trip, though in defending himself Camille succeeds in biting Laurent on the neck. Madame Raquin is in shock after hearing of her son's disappearance. Everybody believes that the drowning was an accident and that the couple actually tried to save Camille. Laurent is still uncertain about whether Camille is truly dead and frequently visits the mortuary, which he persists in although it disturbs him, until he finally finds the dead body there. Thérèse becomes far more nervous and has nightmares; the previously calm and centered Laurent also becomes nervous. Their feelings toward each other are greatly changing, but they still plot to marry without raising suspicion and therefore reap the rewards of their actions. Thérèse acts very subdued around family and acquaintances and Laurent publicly shows great concern and care for her, so Michaud, one of the family's regular visitors, decides that Thérèse should remarry and her ideal husband should be Laurent. They finally marry but are haunted by the memory of the murder; Laurent's bite scar serves as a constant reminder for them both. They have hallucinations of the dead Camille in their bed every night, preventing them from touching each other and quickly driving them even more insane. They vacillate between trying desperately to rekindle their passion to get rid of the corpse hallucinations (and trying to 'heal' the bite scar) and despising each other. Laurent, previously an untalented artist, is suddenly struck with surprising talent and skill, but he can no longer paint a picture (even a landscape) which does not in some way resemble the dead man. Sickened by this, he gives up art. They must also tend to Madame Raquin, who suffered a stroke after Camille's death. She suffers a second stroke and becomes completely paralyzed (except for her eyes), after which Thérèse and Laurent accidentally reveal the murder in her presence during one of their many arguments.[3]

Madame Raquin, previously blissfully happy, is now filled with rage, disgust, and horror. During an evening game of dominoes with friends, Madame Raquin manages to move her finger with an extreme effort of will to trace words on the table: "Thérèse et Laurent ont ...". The complete sentence was intended to be "Thérèse et Laurent ont tué Camille" (Thérèse and Laurent killed Camille). At this point, her strength gives out and the words are interpreted as "Thérèse and Laurent look after me very well".

Thérèse and Laurent find life together intolerable. Laurent has started beating Thérèse, something she deliberately provokes to distract her from her life. Thérèse has convinced herself that Madame Raquin has forgiven her and spends hours kissing her and praying at the disabled woman's feet. The couple argue almost constantly about Camille and who was responsible for his death, so they exist in an endless waking nightmare. They are being driven to rashly plot to kill each other. At the novel's climax, they're about to kill each other when each realizes the other's plan. They break down sobbing in silent agreement of what they should do next, and reflect on their miserable lives. After a final embrace, they commit suicide by taking poison supplied by Laurent, all in front of the hate-filled, watchful gaze of Madame Raquin.

Throughout the book, there are references to chains, cages, tombs, and pits. These contribute to the impression that Laurent and Thérèse are in a state of remorse and are plagued by guilt. The book mentions how they always claw at the chains that bound them together. The shop that Thérèse owns is compared to a tomb, where Thérèse watches corpses walk by in the day.

In his preface to the second edition, Zola writes that he intended to "study temperaments and not characters". To his main characters, he assigns various humors according to Galen's four temperaments: Thérèse is melancholic, Laurent is sanguine, Camille is phlegmatic and Madame is choleric. For Zola, the interactions of these types of personalities could only have the result that plays out in his plot.

Also in his preface, Zola calls both Thérèse and Laurent "human brutes" and the characters are often given animal tendencies. Zola would take up this idea again in his La Bête humaine (1890).

Thérèse Raquin is generally considered to be Zola's first major work. Upon its release in 1867, Thérèse Raquin was a commercial and artistic success for Zola; this led to a reprint in book form in 1868. It gained additional publicity when critic Louis Ulbach (pen name: Ferragus) called Thérèse Raquin "putrid" in a long diatribe for Le Figaro; Zola capitalized on this for publicity and referred to it in his preface to the second edition.[4]

Zola's book provided the clear inspiration for James M. Cain's 1934 novel The Postman Always Rings Twice, which has a similar plot.[5]

Zola adapted the novel into a play, Thérèse Raquin, first staged in 1873. It was not performed in London until 1891, under the auspices of the Independent Theatre Society, since the Lord Chamberlain's Office refused to license it.

Stage productions of Zola's play include:

An opera based on the novel was written by the composer Michael Finnissy. Another opera, Thérèse Raquin, by Tobias Picker, opened in 2000.

The novel was made into the Broadway musical Thou Shalt Not, with music by Harry Connick Jr.

The play The Artificial Jungle by Charles Ludlam was an adaption of the novel, written in the hard-boiled crime style of James M. Cain.

Neal Bell adapted the novel into a play under the same title. It was first produced at New York University by Playwrights Horizons Theatre School on December 3, 1991, directed by Edward Elefterion, with Katie Bainbridge as the title role. Its first professional production was at the Williamstown Theatre Festival on June 30, 1993, directed by Michael Greif, with Lynn Hawley as Thérèse. On July 10, 1994, Michael Greif, in conjunction with La Jolla Playhouse in California, put up the West Coast premiere with Paul Giamatti in the role of Camille. Its professional New York premiere was on October 27, 1997, at the Classic Stage Company, directed by David Esbjornson, with Elizabeth Marvel as Thérèse. The Los Angeles premiere was directed by Charlie Stratton, with Leslie Hope as Thérèse.[7]

A 2014 UK musical, Thérèse Raquin, with music by Craig Adams and book and lyrics by Nona Shepphard, featured Julie Atherton as Thérèse, Tara Hugo as Madame, Jeremy Legat as Camille and Ben Lewis/Greg Barnett as Laurent. After a sold-out run at The Finborough Theatre the Theatre Bench production transferred to Park Theatre in Finsbury Park and was nominated for a West End Frame award. A cast recording was released in 2015.[8]

Film and television adaptations of the novel include:

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.