Thomas M. Messer

American museum director From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Thomas Maria Messer (February 9, 1920 – May 15, 2013) was the director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, including the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City and the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, Italy, for 27 years, longer than any other director of a major New York City arts institution.[2][3]

Thomas M. Messer | |

|---|---|

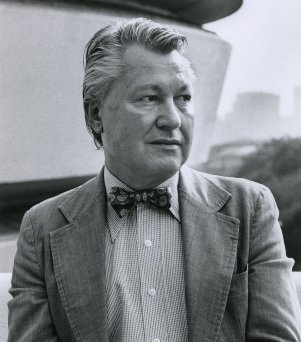

Messer in 1985 | |

| Born | Thomas Maria Messer February 9, 1920 |

| Died | May 15, 2013 (aged 93)[1] |

| Citizenship | U.S. |

| Education | Thiel College, Boston University, CCFS Sorbonne University, MA art history and museology Harvard University |

| Known for | Director of Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation 1961–1988 |

| Spouse | Remedio Garcia Villa (1948– ) |

Born and raised in Czechoslovakia, Messer became a U.S. citizen in 1944 and served in the U.S. Army in World War II. He earned a master's degree in art history and museology from Harvard University. From 1947 to 1961, he worked in a series of art and museum administration positions, the last of which was director of the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston. In 1961, he became director of the Guggenheim Museum in New York. There, he was able to establish the usefulness of the spiral-shaped Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Guggenheim as a venue for the display of art, despite the doubts of critics and artists. Messer was instrumental in expanding the museum's collection during his tenure, especially by persuading Peggy Guggenheim to donate her collection to the Guggenheim Foundation. He retired in 1988 to take up freelance curating, teaching, writing, lecturing.[3][4]

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Messer was born in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia and grew up in Prague. His mother came from a family of musicians, and his father was an art historian and a professor of German.[5] He studied chemistry in Prague until September 2, 1939, when he sailed for England, but the following day England declared war with Germany, and the ship on which he was travelling, the Athenia, was torpedoed and sunk. Messer was rescued and soon travelled to the United States, where he enrolled as an exchange student at Thiel College, Greenville, Pennsylvania. He switched to the study of modern languages at Boston University, Massachusetts, from which he graduated in 1942.[5] After working as a multilingual monitor and interrogator for military intelligence at the Office of War Information in New York, he enlisted in the U.S. Army and became a U.S. citizen in 1944, seeing combat overseas in 1944–1945.[2][6]

After the war, Messer worked at the Office of Military Government, United States in Munich, Germany, studying art for the first time at the Sorbonne in Paris.[5] Receiving his degree in 1947, he returned to the U.S., where he married Remedio Garcia Villa (d. 2002).[6] From 1949 to 1952, he served as the director of the Roswell Museum and Art Center, except for a year's leave of absence, when he studied for a master's degree in art history and museology at Harvard University.[6] He then was assistant director and later director at the American Federation of Arts until 1956.[2] From 1957 to 1961, he was director of the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston and, for part of that time, taught modern art at Harvard.[2][6]

Guggenheim and later years

Summarize

Perspective

Messer took over at the Guggenheim Museum in 1961, at a time when the museum's ability to present art at all was in doubt due to the challenges of working in the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed building's unique continuous spiral ramp gallery that is tilted, with curved walls.[3] Almost immediately, in 1962, he took a risk putting on a large exhibition that combined the Guggenheim's paintings with sculptures on loan from the Hirshhorn Museum.[3] Three-dimensional sculpture, in particular, entailed, "the problem of installing such a show in a museum bearing so close a resemblance to the circular geography of hell," where any vertical object appears tilted in a "drunken lurch" because the slope of the floor and the curvature of the walls could combine to produce vexing optical illusions.[4]

It turned out that the combination could work well in the Guggenheim's space, but, Messer recalled that at the time, "I was scared. I half felt that this would be my last exhibition."[3] Messer had the foresight to prepare by staging a smaller sculpture exhibition the previous year, in which he discovered how to compensate for the space's weird geometry by constructing special plinths at a particular angle, so the pieces were not at a true vertical yet appeared to be so.[4] In the earlier sculpture show, this trick proved impossible for one piece, an Alexander Calder mobile whose wire inevitably hung at a true plumb vertical, "suggesting hallucination" in the disorienting context of the tilted floor.[4]

In 1963, Messer acquired for the museum an important private modern art collection from art dealer Justin K. Thannhauser,[5][7] which originally consisted of 73 pieces.[8][9] Thannhauser's widow Hilde donated additional pieces to the museum's Thannhauser Collection in 1981 and 1991.[10] At Messer's urging, in 1976, Peggy Guggenheim donated her art collection and home in Venice, Italy, the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, to the foundation.[5][11] After her death in 1979, the collection of more than 300 important works was re-opened to the public as the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in 1980.[12] Since 1985, the Guggenheim Foundation has also operated the U.S. Pavilion of the Venice Biennale, an exhibition held every other summer. In 1986, the Foundation purchased the Palladian-style pavilion building.[12][13]

Messer served as director of the Guggenheim Foundation from 1980[14] to 1988.[6] He announced his retirement from the Guggenheim in November 1987, and a search committee found his replacement, Thomas Krens, by 1988.[3] Messer's retirement announcement coincided with the 50th birthday celebration of the Guggenheim Museum. At the exhibition put on in celebration, "virtually every foreign artist who has ever shown at the Guggenheim flew in to pay tribute" to Messer.[15]

From 1990, he was a freelance curator, teacher, writer and arts consultant.[6] Messer died at his home in New York City on May 15, 2013, at the age of 93.[5]

Timeline

Summarize

Perspective

Sources, except as indicated:[2][6]

- 1920 Born Bratislava, Czechoslovakia

- 1924 Moved to Prague at age 3 or 4

- 1926–1939 Elementary school (Czech), Hauptschule (German), Graduated from industrial school (Czechoslovak)

- 1938 Awarded scholarship for exchange studies to U.S., under Institute of International Education, New York

- 1939 Undergraduate at Thiel College, Greenville, Pennsylvania

- 1941–1942 Undergraduate Boston University, Massachusetts

- 1942–43 Multilingual monitor at Office of War Information, New York

- 1944 Enlisted, U.S. Army. U.S. citizenship

- 1944–1945 Combat duty in France, regimental military intelligence.[6][16]

- 1945–1947 Office of Military Government, United States, Munich, Germany

- 1947 Cours de Civilisation Française diploma from Sorbonne University, Paris, France. Return to U.S.

- 1948 Marriage to Remedio Garcia Villa

- 1949–52 Director, Roswell Museum and Art Center

- 1950–1951 Master of Arts in art history and museology, Harvard University (leave of absence from Roswell Museum)

- 1952–53 Assistant Director, American Federation of Arts

- 1953–55 Director of Exhibitions

- 1955–56 Director

- 1956 Consultant and Director, Time Inc.

- 1957–61 Director, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston

- 1960 Adjunct Professor of modern art, Harvard University

- 1961–88 Director, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

- 1980–88 Trustee

- 1966, 1971 Adjunct Professor, Barnard College

- 1966 Senior Fellow of Center For Advanced Study, Wesleyan University

- 1974– Trustee, Center for Inter–American Relations (Percy R. Pyne House)

- 1976–78 Chair, International Exhibitions Committee

- 1977–80 President, MacDowell Colony

- 1980 Director Emeritus, Peggy Guggenheim Collection

- 1981–1988 Director, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

- 1981 Trustee, Americas Society

- 1988 Retired from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

- 1989 Appointed Director Emeritus, Guggenheim

- 1990–2012 Freelance curating, teaching, writing, lecturing and other work in arts and culture.

- n/a Writer and Trustee, Wooster School

- 2013 Death[5]

Notes

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.