Thomas Baty

English lawyer, writer and activist (1869–1954) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Thomas Baty (8 February 1869 – 9 February 1954), also known as Irene Clyde, was an English international lawyer, writer and activist. Baty was a renowned legal scholar and international law expert, spending the majority of a distinguished career as a legal advisor to the Japanese Foreign Office and publishing several works on international law. Baty was also a notable advocate for radical feminism and against binary gender distinctions. Contemporary scholars have described Baty variously as non-binary, genderfluid, transgender, or a trans woman.

Thomas Baty | |

|---|---|

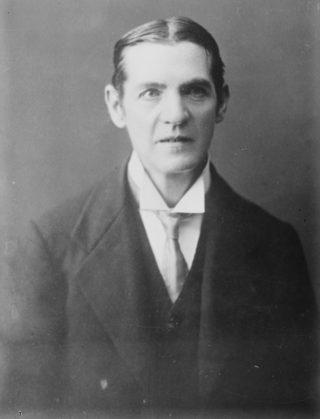

Baty, c. 1915–1920 | |

| Born | 8 February 1869 Stanwix, Cumberland, England |

| Died | 9 February 1954 (aged 85) Ichinomiya, Chiba, Japan |

| Resting place | Aoyama Cemetery, Japan 35.66605°N 139.72229°E |

| Other names | Irene Clyde, Theta |

| Education |

|

| Occupation(s) | International lawyer, writer, activist |

| Years active | 1898–1954 |

| Known for |

|

| Notable work |

|

| Awards | Order of the Sacred Treasure (third class, 1920; second class, 1936) |

| Signature | |

Baty was born in Stanwix, Cumberland. Despite the early death of Baty's father, academic prowess earned Baty a scholarship to The Queen's College, Oxford, where a degree in jurisprudence was completed in 1892, followed by further studies at Trinity College, Cambridge. Baty's career encompassed teaching positions at several prominent universities and a prolific output of writings on international law. Under the name Irene Clyde, Baty published Beatrice the Sixteenth, a feminist utopian novel set in a genderless society, founded the short-lived Aëthnic Union, and co-founded the journal Urania to challenge binary gender categories. Baty's legal career led to Japan in 1916, where Baty's service as a legal adviser to the Japanese government earned Baty the Order of the Sacred Treasure.

During a tenure in Japan, Baty developed a legal philosophy that emphasized effective control over territory as the primary criterion for state recognition, a perspective used to justify Japanese expansionist policies. Baty defended Japan's actions in international forums, including the League of Nations. Despite the geopolitical tensions of World War II, Baty remained in Japan, continuing work for the Japanese government. Baty's alignment with Japanese policies led the British government to consider charges of treason; however, prosecution was ultimately avoided, and Baty's British citizenship was revoked instead. Baty passed away in Ichinomiya, Chiba, and was posthumously honored by Japanese dignitaries.

Life and work

Summarize

Perspective

Early life and education

Thomas Baty was born on 8 February 1869, in Stanwix, Cumberland, the eldest child of William Thomas Baty and his wife Mary (née Matthews).[1] Baty's father, a cabinet-maker, died when Baty was seven,[2] leading to a close relationship in late childhood with Baty's mother and sister.[3]: 26 Baty's uncles financially supported the family, enabling a middle-class home characterised by the "feminine home" concept. This Victorian ideal depicted a nurturing sanctuary dominated by female virtue, fostering spiritual and emotional well-being.[4]

Baty attended Carlisle Grammar School[5] and excelled as a gifted student, earning a scholarship to study at The Queen's College, Oxford.[6] Baty enrolled in 1888 and completed a bachelor's degree in jurisprudence in 1892. Called to the bar in 1898, Baty continued academic pursuits, earning an LL.M. from Trinity College, Cambridge, in June 1901, a D.C.L. from Oxford the same year, and an LL.D. from Cambridge in 1903. Baty was a Civil Law Fellow at Oxford and a Whewell Scholar at Cambridge.[1]

Feminist and anti-gender binary activism

Baty also wrote under the name Irene Clyde. Clyde[note 1] advocated for the abolition of male dominance, the dismantling of gender binaries, the fluidity of biological sex, critical examinations of heterosexual marriage and biological reproduction, and the celebration of female-female relationships.[7]

Beatrice the Sixteenth

In 1909, Clyde published the feminist utopian novel Beatrice the Sixteenth.[7] Set in Armeria, it describes a genderless land of people with feminine characteristics who form life partnerships together. The novel examined perspectives on same-sex love and the gender binary.[8] It is considered a precursor to other feminist utopias and contemporary radical feminist theories on gender and sexuality.[9]

The Aëthnic Union and Urania

In 1911, Clyde founded the Aëthnic Union, a society dedicated to challenging the societal gender binary.[3]: 36–37 In 1916, Clyde, along with Esther Roper, Eva Gore-Booth, Dorothy Cornish, and Jessey Wade—fellow members of the Union—launched Urania, a privately circulated journal. The journal advocated Clyde's opposition to the rigid classification of people into two genders.[10][11][12] "Sex is an accident" and "There are no 'men' and 'women' in Urania" were regular mottos.[13] Clyde also contributed under the name Theta.[14]

Urania became a central focus for Clyde over the next 25 years, until its publication ceased with the onset of the Second World War. Initially released bimonthly and later three times a year, the journal was distributed privately and free of charge. It was printed at various global locations and featured original content, often written by Clyde, alongside reprinted excerpts from books or global mass media, and occasional editorial comments.[15] Subjects of the articles included same-sex relationships, androgyny, and sex changes.[13]

Eve's Sour Apples

In 1934, Clyde published Eve's Sour Apples, a collection of essays criticising gender distinctions and heterosexual marriage. The book envisioned a future where all forms of traditionally masculine behaviour were eradicated and offered guidance on how someone assigned male at birth could adopt a more feminine gender presentation.[8] Clyde also passionately opposed the idea that women's worth was tied to motherhood or maternity, arguing that it was disastrous for "every girl's mind to be filled with the gruesome details of maternity".[7]

Legal career and life in Japan

Early legal career and contributions

Baty's expertise was in the field of international law. After graduation, Baty lectured on international law at Nottingham University and served as a degree examiner at Oxford, London, and Liverpool universities. During this time, Baty became a prolific writer on international law.[6] Baty served as the honorary general secretary of the International Law Association from 1905 to 1916 and acted as junior counsel on the Zamora case. Baty was an associate member of the Institut de Droit International from 1921 onwards.[1]

Engagement with the Japanese government

Following the outbreak of the First World War, Baty took part in the establishment of the Grotius Society, established in London in 1915. As one of the original members of that society, Baty became acquainted with Isaburo Yoshida, Second Secretary of the Embassy of Japan in London and an international law scholar from the graduate school of the Tokyo Imperial University. The Japanese government was at that time searching for a foreign legal adviser following the death of Henry Willard Denison, a US citizen who served in that position until his death in 1914. Baty applied for that position in February 1915. The Japanese government accepted the application and Baty came to Tokyo in May 1916 to start work at the Japanese Foreign Office. In 1920, Baty was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure, third class, for service as a legal adviser,[6] and in 1936, Baty received the second class of the same order.[16]

In 1927, Baty participated as part of the Japanese delegation to the Geneva Naval Conference on disarmament, marking the only public appearance as a legal adviser for the Japanese government. The majority of Baty's work focused on writing legal opinions. Baty renewed working contracts with the Japanese Foreign Office several times and, in 1928, became a permanent employee of the ministry.[16]

Defence of Japanese military actions

Baty's legal philosophy evolved while working for the Japanese government and was designed to justify Japanese actions of encroaching upon the sovereignty of China.[16] Following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1932 and the establishment of Manchukuo, Baty defended Japan's position in the League of Nations and advocated for the new state's membership. Baty also wrote legal opinions justifying the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937.[16] In addition, Baty donated 1,000 yen five times, a substantial sum for the time, to aid the families of fallen Japanese soldiers describing such actions as humanitarian, aimed at easing the grief of mothers, and arguing the war was avoidable if the League of Nations had accepted Baty's views and Japan's position.[16]

Baty's main argument was that the recognition of states must depend on one factor alone—effective control by the military and security forces of the government over the state's territory, and not on preconceived definitions of what the state should be. Based on this reasoning, Baty opposed the practice of granting de facto recognition, asserting that only final and irrevocable recognition should be applied. Baty accused the Western international community of hypocrisy for using de facto recognition as a tool to engage in certain transactions with governments of states Baty considered unfriendly, without fully committing to accepting those states as part of the international community.[17]

World War II and aftermath

In July 1941, the Japanese government froze the assets of foreigners residing in Japan or its colonial possessions as a retaliatory measure against similar actions taken by the United States. Baty was exempt from this policy due to service for the Japanese government. Despite the outbreak of war with the British Empire in December 1941, Baty chose to remain in Japan, rejecting efforts by the British Embassy to arrange repatriation. Baty continued working for the Japanese government throughout the war and defended Japan's policy of conquest as a response to Western imperialism in Asia. In late 1944, Baty questioned the legitimacy of pro-Allied governments established after the end of the German occupation in Europe.[16] Baty also contributed articles to Japanese newspapers on British and American affairs.[18]

Following the Japanese surrender in 1945, the British Ministry of Foreign Affairs considered indicting Baty for treason. However, the Central Liaison Office, a British government agency operating in Japan, opined that Baty's involvement with the Japanese government during the war was insignificant. Additionally, some legal advisers within the British government argued against prosecution on the grounds of Baty's advanced age. Ultimately, the British government chose to revoke Baty's British citizenship and allowed Baty to remain in Japan.[16]

For the rest of Baty's life, Baty resided in a villa in Ichinomiya, Chiba, given to Baty by Kano Hisarō. Baty continued to work for the Japanese government until 1952.[19]

Death

Baty died of a cerebral haemorrhage at the age of 85, in Ichinomiya, on 9 February 1954.[20] The Emperor of Japan sent floral tributes to Baty's funeral, as did many of the people who knew Baty. Eulogies were delivered by Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, Foreign Minister Katsuo Okazaki, Saburo Yamada (President of the Japanese Society of International Law) and Iyemasa Tokugawa (a former colleague). Baty was buried in Aoyama Cemetery, Tokyo, alongside Baty's sister and mother.[2]

Baty, who authored approximately 18 books on legal matters, died shortly after completing the first proof of Baty's last book, International Law in Twilight. The book provides commentary on legal issues as well as history, politics, and problems related to Japan and the Far East, drawing from extensive experience as a legal advisor to the Japanese Foreign Office.[21]

Gender identity

Summarize

Perspective

Baty's personal reflections

In 1926, Baty wrote a declaration on love and marriage that was privately shared with close friends and published posthumously. In the text, Baty confessed:[4]

From my earliest years I hated sex. The reason was that I wanted to be a girl. I saw that ladies, while admittedly more graceful and sweet than men, were also just as determined and noble. I could not bear to be relegated to the ranks of rough and stern men.

In an autobiographical sketch in Alone in Japan, Baty reflected: "From earliest days, adored Beauty and Sweetness; considered ladies had both, as well as Persistence and Tenacity. Therefore, longed passionately to be a lady—and have continued to do so."[22]

Insights from friends and observers

Baty publicly presented as Thomas Baty to most of society.[3]: 21–22 Friends observed Baty's reserved nature, gentle demeanour, and traditionally feminine traits, such as speaking in the women's style of Japanese and fastening garments from right to left.[22] Baty also wore women's clothes and accessories.[4] Hugh Keenleyside, a Canadian diplomat in Japan, described Baty as a "transvestite", who occasionally entertained guests while dressed in a gown.[23] Friends also witnessed a transition from Thomas Baty to Irene Clyde, noting that one identity gradually faded as the other emerged:[3]: 21–22

When he extended his hand in greeting his sombre eyes lit up, his withdrawn expression melted away. Dr Baty, Chief Legal Advisor to the Foreign Office of Japan, disappeared and in his place stood Irene Clyde, a gentle, kindly, witty, and intelligent elderly lady.

Modern interpretations

Baty has been described variously by contemporary scholars as non-binary,[24][25] genderfluid,[3]: 21–22 [25] transgender,[11][12][25] or a trans woman.[26] Sandra Duffy asserts that Baty's gender identity remains ambiguous.[25] Alison Oram argues that Baty's desire "to be a lady" challenges efforts by some theorists and historians to trace a continuous transgender identity through history. While there are similarities to late twentieth-century transgender politics, Baty's self-perception was shaped by a specific historical context, differing significantly from identities influenced by later advancements in medical transition.[27]

Personal life

Summarize

Perspective

Baty was a strict vegetarian since the age of 19 and later served as vice-president of the British Vegetarian Society.[2] Baty was also a member of the Humanitarian League[28] and the Animal Defence and Anti-Vivisection Society.[29]

Influenced by the writings of Thomas Carlyle, Baty came to perceive the unity of all religions and disregarded the specific historical contexts of Hebrew and Christian traditions. Baty subsequently became a Theosophist and a follower of Shinto.[15]

An important person in Baty's life was Baty's sister Anne, who accompanied Baty to Japan in 1916 alongside their mother (who died in the same year). Anne lived with Baty until Anne's death in Nikkō on 22 January 1945.[2]

Baty's recreations included a passion for music, heraldry, and the sea, and Baty was described as a conservative.[1] Baty also had a passion for literature and localism, particularly the formation of small, self-sustaining communities.[23] While living in Tokyo, Baty embraced a leisure-class lifestyle, spending summers at Lake Chuzenji with Anne. At the lake, Baty owned and sailed a boat named The Ark and socialised at the Nantaisan Yacht Club. The exclusivity of the resort was marked by its mainly diplomatic occupants and daily sailboat races.[16]

Baty never married. Some evidence suggests that Baty was disillusioned with Victorian sexual norms and disgusted by the then accepted notions of male domination over women.[4] Baty described a personal philosophy as that of a radical feminist and a pacifist,[30] arguing that masculine traits lead to war, while feminine traits reject it. Baty concluded that ending war required prioritising feminine characteristics.[2] Baty was also a supporter of the feminist struggle in Japan.[31]

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Baty's later years inspired Japanese writer Ayako Sono's 1954 short story "Grave of the Sea". Although the story is set in Hakone instead of Nikkō, where Baty resided, it portrays a tale of a difficult life in a foreign land after the war. A notable line from the main character reads: "When I die, please throw my bones in the sea. I don't need a grave."[32]

In 1959, Baty's memoirs, Alone in Japan: The Reminiscences of an International Jurist Resident in Japan 1916–1954, were published, edited by Motokichi Hasegawa.[33]

In 1993, scholars Daphne Patai and Angela Ingram uncovered that starting in 1909, Baty had been writing about feminism and gender using the name Irene Clyde.[34] Baty's strong opposition to the restrictive gender conventions of the time, coupled with a personal defiance of these norms in Baty's private life, is recognised by contemporary scholars as establishing Baty as a transgender pioneer.[34][35]

Baty's unwavering support for Japan during the war made Baty a controversial figure in international law.[2] Critics have described Baty as both a traitor and an apologist for imperialism.[36] In 2004, a commemorative seminar was held at the University of Tokyo on the 50th anniversary of Baty's death to reappraise Baty's contributions to international law. It featured work from the scholars Vaughan Lowe, Martin Gornall and Hatsue Shinohara.[37]

Works

Books

As Thomas Baty

- International Law in South Africa (London: Stevens and Haynes, 1900)

- International Law (New York: Longmans, Green, and Co.; London; John Murray, 1909)

- Polarized Law (London: Stevens and Haynes, 1914)

- (with John H. Morgan) War: Its Conduct and Legal Results (New York: E. P. Dutton and Co., 1915)

- Vicarious Liability (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1916)

- The Canons of International Law (London: John Murray, 1930)

- Academic Colours (Tokyo: Kenkyusha Press, 1934)

- International Law in Twilight (Tokyo: Maruzen Publishing Co., 1954)

- (ed. Motokichi Hasegawa) Alone in Japan: The Reminiscences of an International Jurist Resident in Japan 1916–1954 (Tokyo: Maruzen Publishing Co., 1959), memoirs

- (ed. Julian Franklyn) Vital Heraldry (Edinburgh: The Armorial Register, 1962)

As Irene Clyde

- Beatrice the Sixteenth (London: George Bell & Sons, 1909; New York: Macmillan, 1909)

- Eve's Sour Apples (London: Eric Partridge at the Scholartis Press, 1934)

Articles

- "The Root of the Matter". Macmillan's Magazine. Vol. 88. 1902–1903. pp. 194–198.

- "The Aëthnic Union". The Freewoman. 1 (14): 278–279. 22 February 1912.

- "Can an Anarchy be a State?" American Journal of International Law, Vol. 28, No. 3 (Jul., 1934), pp. 444–455

- "Abuse of Terms: 'Recognition': 'War'" American Journal of International Law, Vol. 30, No. 3 (Jul., 1936), pp. 377–399 (advocating the recognition of Manchukuo)

- "The 'Private International Law' of Japan" Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Jul., 1939), pp. 386–408

- "The Literary Introduction of Japan to Europe" Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 7, No. 1/2 (1951), pp. 24–39, Vol. 8, No. 1/2 (1952), pp. 15–46, Vol. 9, No. 1/2 (1953), pp. 62–82 and Vol. 10, No. 1/2 (1954), pp. 65–80

Notes

- This article uses the name Irene Clyde when referring to works written under that name.

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.