2008 Kosovo declaration of independence

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The 2008 Kosovo declaration of independence, which proclaimed the Republic of Kosovo to be an independent and sovereign state, was adopted at a meeting held on 17 February 2008 by 109 out of the 120 members of the Assembly of Kosovo, including the Prime Minister of Kosovo, Hashim Thaçi, and by the President of Kosovo, Fatmir Sejdiu (who was not a member of the Assembly).[1] It was the second declaration of independence by Kosovo's Albanian-majority political institutions; the first was proclaimed on 7 September 1990.[2]

The legality of the declaration has been disputed. Serbia sought international validation and support for its stance that the declaration was illegal, and in October 2008 requested an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice.[3] The Court determined that the declaration did not violate international law.[4]

As a result of the ICJ decision, a joint Serbia–EU resolution was passed in the United Nations General Assembly which called for an EU-facilitated dialogue between Belgrade and Pristina to "promote cooperation, achieve progress on the path to the European Union and improve the lives of the people."[5] The dialogue resulted in the 2013 Brussels deal between Belgrade and Pristina which abolished all of the Republic of Serbia's institutions in Kosovo. Dejan Pavićević is the official representative of Government of Serbia in Pristina.[6] Valdet Sadiku is the official representative of Kosovo to Serbia.[7]

History

Summarize

Perspective

Background

The Province of Kosovo took shape in 1945 as the Autonomous Region of Kosovo and Metohija within Socialist Yugoslavia, as an autonomous region within the People's Republic of Serbia.[8] Initially a ceremonial entity, more power was devolved to Kosovan authorities with each constitutional reform. In 1968 it became the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo and in 1974, a new Yugoslav constitution enabled the autonomous province to function with some elements of self-governance including an assembly, government and a right to its own constitution.[9][10] Increasing ethnic tension throughout Yugoslavia in the late 1980s amid rising nationalism among its nations eventually led to a decentralised state: this facilitated Serbian President Slobodan Milošević's effective termination of the privileges awarded to the Kosovar assembly in 1974. The move attracted criticism from the leaderships of the other Yugoslav republics but no higher authority was in place to reverse the measure. In response to the action, the Kosovo Assembly voted on 2 July 1990 to declare Kosovo an independent state, and this received recognition from Albania.[11][12] A state of emergency and harsh security rules were subsequently imposed against Kosovo's Albanians following mass protests. The Albanians established a "parallel state" to provide education and social services while boycotting or being excluded from Yugoslav institutions.

Kosovo remained largely quiet through the Yugoslav wars. The severity of the Yugoslav government in Kosovo was internationally criticised. In 1996, the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) began attacking federal security forces. The conflict escalated until Kosovo was on the verge of all-out war by the end of 1998. In January 1999, NATO warned that it would intervene militarily against Yugoslavia if it did not agree to the introduction of an international peacekeeping force and the establishment of local government in Kosovo. Subsequent peace talks failed and from 24 March to 11 June 1999, NATO carried out an extensive bombing campaign against FR Yugoslavia including targets in Kosovo itself.[13] The war ended with Milošević agreeing to allow NATO "peacekeepers" into Kosovo and withdrawing all security forces so as to transfer governance to the United Nations.[13][14]

Build-up

A NATO-led Kosovo Force (KFOR) entered the province following the Kosovo War, tasked with providing security to the UN Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK). Before and during the handover of power, an estimated 100,000 Serbs and other non-Albanians, mostly Romani people, fled the province for fear of reprisals. In the case of the non-Albanians, the Romani in particular were regarded by many Albanians as having assisted federal forces during the war. Many left along with the withdrawing security forces, expressing fears that they would be targeted by returning Albanian refugees and KLA fighters who blamed them for wartime acts of violence. Thousands more were driven out by intimidation, attacks and a wave of crime after the war.

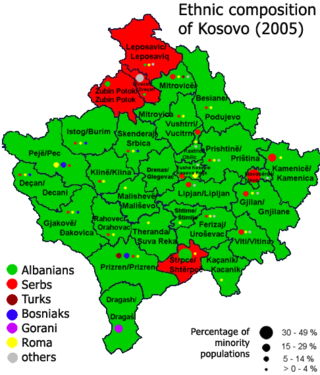

Large numbers of refugees from Kosovo still live in temporary camps and shelters in Serbia proper. In 2002, Serbia and Montenegro reported hosting 277,000 internally displaced people (the vast majority being Serbs and Roma from Kosovo), which included 201,641 persons displaced from Kosovo into Serbia proper, 29,451 displaced from Kosovo into Montenegro, and about 46,000 displaced within Kosovo itself, including 16,000 returning refugees unable to inhabit their original homes.[15][16] Some sources put the figure far lower. In 2004 the European Stability Initiative estimated the number of displaced people as being only 65,000, with 130,000 Serbs remaining in Kosovo, though this would leave a significant proportion of the pre-1999 ethnic Serb population unaccounted-for. The largest concentration of ethnic Serbs in Kosovo is in the north of the province above the Ibar river, but an estimated two-thirds (75,000) of the Serbian population in Kosovo continue to live in the Albanian-dominated south of the province.[17]

In March 2004, there was a serious inter-ethnic clash between Kosovo Albanians and Kosovo Serbs that led to 27 deaths and significant property destruction. The unrest was precipitated by misleading reports in the Kosovo Albanian media which falsely claimed[citation needed] that three Kosovo Albanian boys had drowned after being chased into the Ibar River by a group of Kosovo Serbs. UNMIK peacekeepers and KFOR troops failed to contain a raging gun battle between Serbs and Albanians.[18] The Serbian Government called the events the March Pogrom.[19]

In 2005 the Swiss Federal Councillor responsible for Foreign Affairs, Micheline Calmy-Rey, was the first official of a country to publicly express support for the independence of Kosovo. [20][21][22]

International negotiations began in 2006 to determine the final status of Kosovo, as envisaged under UN Security Council Resolution 1244 which ended the Kosovo conflict of 1999. Serbia's continued sovereignty over Kosovo was recognised internationally. The vast majority of the province's population sought independence.

Declaration of 2008–present

The 2008 declaration was a product of failed negotiations concerning the adoption of the Ahtisaari plan, which broke down in the fall of 2007. The plan, prepared by the UN Special Envoy and former President of Finland, Martti Ahtisaari, stipulated a sort of supervised independence for Kosovo, without expressly using the word "independence" among its proposals.[23] Under the plan, Kosovo would gain self-governance under the supervision of the European Union, and become obligated to expressly protect its minorities' rights by means of a constitution and a representative government.[24] Kosovo would be accorded its own national symbols such as a flag and a coat of arms, and be obligated to carry out border demarcation on the border with the Republic of North Macedonia border.[24] The Albanian negotiators supported the Ahtisaari plan essentially in whole, and the plan gained the backing of the European Union and of the United States.[25] However, Serbia and Russia rejected it outright, and no progress was possible on the United Nations front.

Faced with no progress on negotiations in sight, the Kosovars decided to unilaterally proclaim the Republic of Kosovo, obligating themselves in the process to follow the Ahtisaari plan's provisions in full.[23] As of mid-April 2008, this has largely been the case, with the new Republic adopting a constitution written by local and international scholars protecting minority rights and providing for a representative government with guaranteed ethnic representation, which law is to take effect on 15 June 2008. It also adopted some of its national symbols already, including the flag and coat of arms, while work continues on defining the anthem. It has also engaged, albeit with a delay, in the border demarcation talks with North Macedonia, initially insisting on being recognised first but dropping this condition later on.

The 2008 Kosovo declaration of independence elicited mixed reaction internationally and a polarised one domestically, the latter along the division of Kosovo Serbs vs. the Kosovo Albanians. Accordingly, effective control in Kosovo has also fractured along these lines.

After 13 years of international oversight, Kosovo's authorities formally obtained full unsupervised control of the region (less only North Kosovo) on 10 September 2012 when Western Powers terminated their oversight. The International Steering Group, in its final meeting with the authorities in Pristina, declared that the Comprehensive Proposal for the Kosovo Status Settlement, known as the Ahtisaari plan after its Finnish UN creator, had been substantially implemented.[26] Nonetheless, as of November 2015, United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo still functions, albeit at a greatly reduced capacity.

Political background

Summarize

Perspective

After the end of the Kosovo War in 1999, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 1244 to provide a framework for Kosovo's interim status. It placed Kosovo under transitional UN administration, demanded a withdrawal of Serbian security forces from Kosovo and envisioned an eventual UN-facilitated political process to resolve the status of Kosovo.

In February 2007, Martti Ahtisaari delivered a draft status settlement proposal to leaders in Belgrade and Pristina, the basis for a draft UN Security Council Resolution which proposed 'supervised independence' for the province. By early July 2007 a draft resolution, backed by the United States and the European Union members of the Security Council, had been rewritten four times to try to accommodate Russian concerns that such a resolution would undermine the principle of state sovereignty. However, it had still not found agreement.[27] Russia, which holds a veto in the Security Council as one of five permanent members, stated that it would not support any resolution which was not acceptable to both Serbia and the Kosovo Albanians.[28] While most observers had, at the beginning of the talks, anticipated independence as the most likely outcome, others suggested that a rapid resolution might not be preferable.[29]

The talks finally broke down, late 2007 with the two sides remaining far apart, with the minimum demands of each side being more than the other was willing to accept.

At the turn of 2008, the media started reporting that the Kosovo Albanians were determined to proclaim independence.[citation needed] This came at the time when the ten-year anniversary of the Kosovo War was looming (with the five-year anniversary being marked by violent unrest); the U.S. President George W. Bush was in his last year in power and not able to seek re-election; and two nations which had previously seceded from Yugoslavia were in important political positions (Slovenia presiding over the EU and Croatia an elected member of the UN Security Council). The proclamation was widely reported to have been postponed until after the 2008 Serbian presidential election, held on 20 January and 3 February, given that Kosovo was an important topic of the election campaign.

Adoption and terms of the declaration of independence

Summarize

Perspective

The text declaration of independence is shown in the Albanian language with an English translation below:

"Ne, udhëheqësit e popullit tonë, të zgjedhur në mënyrë demokratike, nëpërmjet kësaj Deklarate shpallim Kosovën shtet të pavarur dhe sovran. Kjo shpallje pasqyron vullnetin e popullit tonë dhe është në pajtueshmëri të plotë me rekomandimet e të Dërguarit Special të Kombeve të Bashkuara, Martti Ahtisaari, dhe Propozimin e tij Gjithëpërfshirës për Zgjidhjen e Statusit të Kosovës."

"We, the democratically elected leaders of our people, hereby declare Kosovo to be an independent and sovereign state. This declaration reflects the will of our people and it is in full accordance with the recommendations of UN Special Envoy Martti Ahtisaari and his Comprehensive Proposal for the Kosovo Status Settlement. We declare Kosovo to be a democratic, secular and multi-ethnic republic, guided by the principles of non-discrimination and equal protection under the law."

The declaration of independence was made by members of the Kosovo Assembly as well as by the President of Kosovo meeting in Pristina, the capital of Kosovo, on 17 February 2008. It was approved by a unanimous quorum, numbering 109 members. Eleven deputies representing the Serbian national minority boycotted the proceedings. All nine other ethnic minority representatives were part of the quorum.[30] The terms of the declaration state that Kosovo's independence is limited to the principles outlined by the Ahtisaari plan. It prohibits Kosovo from joining any other country, provides for only a limited military capability, states that Kosovo will be under international supervision and provides for the protection of minority ethnic communities.[31] The original papyrus version of the declaration signed that day is in the Albanian language.[32] The Albanian text of the declaration is the sole authentic text.[32]

International disputes

Summarize

Perspective

Legality of the declaration

On 18 February 2008 the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia declared Kosovo's declaration of independence as null and void per the suggestion of the Government of the Republic of Serbia, after the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Serbia deemed the act illegal arguing it was not in coordination with the UN Charter, the Constitution of Serbia, the Helsinki Final Act, UN Security Council Resolution 1244 (including the previous resolutions) and the Badinter Commission.[33]

According to writer Noel Malcolm, the 1903 constitution was still in force at the time that Serbia annexed Kosovo[34][35][36] during the First Balkan War. He elaborates that this constitution required a Grand National Assembly before Serbia's borders could be expanded to include Kosovo; but no such Grand National Assembly was ever held. Constitutionally, he argues, Kosovo should not have become part of the Kingdom of Serbia. It was initially ruled by decree.[37][38][page needed]

The Contact Group had issued in 2005 the Guiding Principles upon which the final status of Kosovo shall be decided.[39]

Precedent or special case

Recognition of Kosovo's independence is controversial. A number of countries fear that it is a precedent, affecting other contested territories in Europe and non-European parts of the former Soviet Union, such as Abkhazia and South Ossetia.[40][41]

The text of Kosovo's declaration of independence addressed this issue by stating "...Observing that Kosovo is a special case arising from Yugoslavia's non-consensual breakup and is not a precedent for any other situation, Recalling the years of strife and violence in Kosovo, that disturbed the conscience of "all civilized people"..." However, Ted Galen Carpenter of the Cato Institute stated the view of Kosovo being sui generis and setting no precedent is "extraordinarily naïve".[40]

United Nations involvement

The newly proclaimed republic has not been seated at the United Nations, as it is generally believed that any application for UN membership would be vetoed by Russia.[42] Russia vowed to oppose Kosovo's independence with a "plan of retaliation".[42][43] Serbia has likewise proactively declared the annulment of Kosovo's independence and vowed to oppose Kosovo's independence with a package of measures intended to discourage the international recognition of the republic.[44]

On 8 October 2008, the UN General Assembly voted to refer Kosovo's independence declaration to the International Court of Justice; 77 countries voted in favour, 6 against and 74 abstained. The ICJ was asked to give an advisory opinion on the legality of Kosovo's declaration of independence from Serbia in February.[45] The court delivered its advisory opinion on 22 July 2010; by a vote of 10 to 4, it declared that "the declaration of independence of the 17th of February 2008 did not violate general international law because international law contains no 'prohibition on declarations of independence'."[46]

Reactions to the declaration of independence

Summarize

Perspective

Kosovo

States that formally recognise Kosovo

States that do not recognise Kosovo

States that recognized Kosovo and later withdrew that recognition

Reactions in Kosovo

Kosovo Albanians

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2009) |

Ethnic Albanians in Kosovo greeted the news with celebration.[47][48][49]

Kosovo Serbs

The bishop of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Kosovo, Artemije Radosavljević, reacted in anger, stating that Kosovo's independence was a "temporary state of occupation", and that "Serbia should buy state of the art weapons from Russia and other countries and call on Russia to send volunteers and establish a military presence in Serbia."[50]

In North Kosovo, a UN building housing a courthouse and jail was attacked by a hand grenade, causing slight damage but no casualties. An unexploded grenade was found across the street, near a hotel that houses EU officials.[51]

An explosive device was detonated in Mitrovica, damaging two vehicles. No casualties or injuries were reported.[52]

Serb protestors in Kosovo set fire to two border crossings on Kosovo's northern border. Both crossings are staffed by Kosovar and UNMIK police. No injuries were reported in the attacks, but the police withdrew until KFOR soldiers arrived.[53]

A Japanese journalist wearing a UN uniform was beaten by Serbs in northern Mitrovica.[54]

Hundreds of Serbs protested in the Kosovo town of Mitrovica on 22 February, which was somewhat peaceful aside from some stone-throwing and a little fighting.[55]

On 14 March 2008 Serb protesters forcibly occupied the UN courthouse in the northern part of Kosovska Mitrovica. On 17 March, UNMIK peacekeepers and KFOR troops entered the courthouse to end the occupation. In the following clashes with several hundred protesters, one Ukrainian UNMIK police officer was killed, over 50 persons on each side were wounded and one UNMIK and one KFOR vehicle were torched. The UNMIK police withdrew from northern Mitrovica leaving KFOR troops to maintain order.[56][57]

The Community Assembly of Kosovo and Metohija first met on 28 June 2008, to coordinate Serb responses to the new government.

Serbian reaction

Official reaction by the Government of Serbia included instituting pre-emptively on 12 February 2008 an Action Plan, which stipulated, among other things, recalling the Serbian ambassadors for consultations in protest from any state recognising Kosovo,[58] issuing arrest warrants for Kosovo leaders for high treason,[59] and even dissolving the government on grounds of lack of consensus to deal with Kosovo, with new elections scheduled for 11 May 2008,[60][61] as well as a rogue minister proposing partitioning Kosovo along ethnic lines,[62] which initiative was shortly thereafter disavowed by the full Government, as well as the President.[63] Late in March the government disclosed its intent to litigate the issue at the International Court of Justice and seek support at the United Nations General Assembly in September 2008.[64]

The Prime Minister of Serbia, Vojislav Koštunica, has blamed the United States for being "ready to violate the international order for its own military interests" and stated that "Today, this policy of force thinks that it has triumphed by establishing a false state. [...] As long as the Serb people exist, Kosovo will be Serbia."[65] Slobodan Samardžić, the Serb minister for Kosovo, stated that, "A new country is being established by breach of international law [...] It's better to call it a fake country."[66] However, the Serbian government says they will not respond with violence.[67]

On 17 February, about 2,000 Serbs protested at the United States Embassy in Belgrade, with some throwing stones and firecrackers at the building before being driven back by riot police.[48] Protestors also broke windows of the embassy of Slovenia, the state that controlled the EU presidency.[68] In Belgrade and Novi Sad, McDonald's restaurants were damaged by protestors.[69] The Serbian division of U.S. Steel, based in Smederevo, had a false bomb threat called in.[70]

The Crown Council of House of Karadjordjevic, a former royal family of Serbia and Yugoslavia, rejected Kosovo's declaration of independence, saying that: "Europe had diminished its own morale, embarrassed its own history and shown that it carries within its organism the virus of its own downfall", and that "it is a defeat of the idea of democracy... a defeat of the universally accepted rules of international law", and that a "part of the project of Mussolini and Hitler has finally been accomplished, in the territory of Serbia".[71]

On 21 February, there were large demonstrations by Serbs in Belgrade. There were more than 500,000 protesters. Most protesters were non-violent, but small groups attacked the United States and Croatian embassies. A group broke into The United States embassy, set it on fire, and attempted to throw furniture through the windows. The embassy was empty, except for security personnel. No embassy staff were injured, but a corpse was found; embassy spokeswoman Rian Harris stated that the embassy believes it to be an attacker.[72] Police took 45 minutes to arrive at the scene, and the fire was only then put out. US ambassador to the UN Zalmay Khalilzad was "outraged", and requested the UN Security Council immediately issue a statement "expressing the council's outrage, condemning the attack, and also reminding the Serb government of its responsibility to protect diplomatic facilities." The damage to the Croatian embassy was less serious.[72]

The Turkish and British embassies were also attacked, but police were able to prevent damage. The interior of a McDonald's was damaged. A local clinic admitted 30 injured, half of whom were police; most wounds were minor.[72]

The Security Council responded to these incidents by issuing a unanimous statement that, "The members of the Security Council condemn in the strongest terms the mob attacks against embassies in Belgrade, which have resulted in damage to embassy premises and have endangered diplomatic personnel," noting that the 1961 Vienna Convention requires host states to protect embassies.[73]

On 22 February, the United States embassy in Serbia ordered the temporary evacuation of all non-essential personnel, after the protests and attacks on the embassy. Rian Harris, a U.S. embassy spokeswoman, explained the evacuation to AFP saying that "Dependents are being temporarily ordered to depart Belgrade. We do not have confidence that Serbian authorities can provide security for our staff members."[55]

Reactions in the former Yugoslavia

On 23 February, 44 protesters were arrested after burning the Serbian flag, in the main square of Zagreb (Croatia), following Serb protesters attacking the Croatian embassy in Belgrade, Serbia.[74]

Hundreds of Bosnian Serb demonstrators broke away from a peaceful rally in Banja Luka on 26 February 2008 and headed for the United States Embassy's office there, clashing with police along the way.[74]

In Montenegro, protests were held in Podgorica on 19 February. Protesters waved flags of the Serb People's Party and the Serbian Radical Party. Serb parties led by the Serb List are calling for a protest on 22 February to protest the independence bid.[75]

International reaction

Unlike the 1990 Kosovo declaration of independence, which only Albania recognised,[76] Kosovo's second declaration of independence has received 111 diplomatic recognitions. However, many states have also showed their opposition to Kosovo's declaration of independence, most notably India, China and Russia. Serbia announced before the declaration that it would withdraw its ambassador from any state which recognised independent Kosovo.[77] Serbia, however, maintains embassies in many countries which recognise Kosovo, including Albania, Canada, Croatia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, South Korea, Turkey, the UAE, the UK, and the US.[78]

Reaction within the European Union

On 18 February 2008 the EU presidency announced after a day of intense talks between foreign ministers that member countries were free to decide individually whether to recognise Kosovo's independence. The majority of EU member states have recognised Kosovo, but Cyprus, Greece, Romania, Slovakia and Spain have not.[79] Some Spanish people (scholars or from the Spanish Government or opposition parties) challenged the comparison made by the Basque Government that way of Kosovo's independence could be a path for the independence of the Basque Country and Catalonia.[80]

Shortly before Kosovo's declaration of independence, the European Union approved deployment of a non-military 2,000-member Rule of Law mission, "EULEX", to develop further Kosovo's police and justice sector. All twenty-seven members of the EU approved the EULEX mandate, including the minority of EU countries that have still not recognised Kosovo's independence. Serbia has claimed that this is an occupation and that the EU's move is illegal.[81]

Outside the EU

United States president George W. Bush welcomed the declaration of independence as well as its proclamation of friendship with Serbia, stating: "We have strongly supported the Ahtisaari plan [implying Kosovo's independence …]. We are heartened by the fact that the Kosovo government has clearly proclaimed its willingness and its desire to support Serbian rights in Kosovo. We also believe it's in Serbia's interests to be aligned with Europe and the Serbian people can know that they have a friend in America."[82]

Russia reacted with condemnation, stating they "expect the UN mission and NATO-led forces in Kosovo to take immediate action to carry out their mandate [...] including the annulling of the decisions of Pristina's self-governing organs and the taking of tough administrative measures against them."[82]

In Tirana, the capital of Albania, 'Kosovo Day' was held as a celebration,[83] and a square in central Tirana was named for this occasion.[84]

Turkish Prime Minister Tayyip Erdoğan phoned Prime Minister Hashim Thaçi, commenting on the declaration of independence, and that it "will bring to Balkans peace and stability".[85]

The Republic of China's (commonly known as Taiwan; non-UN member) Foreign Ministry stated "We congratulate the Kosovo people on their winning independence and hope they enjoy the fruits of democracy and freedom. [...] Democracy and self-determination are the rights endorsed by the United Nations. The Republic of China always supports sovereign countries' seeking democracy, sovereignty and independence through peaceful means."[86] Taiwan's political rival, the People's Republic of China, responded quickly, saying that "Taiwan, as a part of China, has no right and qualification at all to make the so-called recognition".[87]

Amongst Southeast Asian countries where Muslim separatist movements were active in at least three states, Indonesia, with the world's largest Muslim population, deferred recognition of an independent Kosovo,[88] while the Philippines declared it will not oppose, nor support Kosovo's independence.[89][90] Both countries face pressures from Muslim separatist movements within their territories, notably Aceh and southern Mindanao respectively. Vietnam expressed opposition,[91] while Singapore reported that it was still studying the situation.[92] Malaysia, which headed the Organisation of the Islamic Conference at the time, formally recognized Kosovo's sovereignty three days after its independence.[93]

Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd backed Kosovan independence on the morning of 18 February, saying "This would appear to be the right course of action. That's why, diplomatically, we would extend recognition at the earliest opportunity."[94] New Zealand's Former Prime Minister Helen Clark said that New Zealand would neither recognise nor not recognise an independent Kosovo.[95] Pro-Independence rallies were held by ethnic Albanians in Canada in the days leading up to the declaration.[96]

On 9 November 2009 New Zealand formally recognised Kosovo's independence.

The President of Northern Cyprus (a state not recognised by the UN), Mehmet Ali Talat, saluted the independence of Kosovo and hopes that the state is respected and assisted, in staunch opposition to the position of the Republic of Cyprus.[97]

United Nations

Following a request from Russia, the United Nations Security Council held an emergency session in the afternoon of 17 February 2008.[81] The United Nations Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, issued a statement that avoided taking sides and urged all parties "to refrain from any actions of statements that could endanger peace, incite violence or jeopardize security in Kosovo or the region."[98] Speaking on behalf of six countries—Belgium, Croatia, France, Germany, Italy and the United States—the Belgian ambassador expressed regret "that the Security Council cannot agree on the way forward, but this impasse has been clear for many months. Today's events... represent the conclusion of a status process that has exhausted all avenues in pursuit of a negotiated outcome."[99]

ICJ ruling

On 22 July 2010, the International Court of Justice ruled that the declaration did not violate international law, holding that the authors were acting in their capacity as representatives of the people of Kosovo outside the framework of the interim administration (the Assembly of Kosovo and the Provisional Institutions of Self-Government), and were therefore not bound by the Constitutional Framework (promulgated by UNMIK) or by UNSCR1244 that is addressed only to United Nations Member States and organs of the United Nations.[1] Prior to the announcement Hashim Thaçi said there would be no "winners or losers" and that "I expect this to be a correct decision, according to the will of Kosovo's citizens. Kosovo will respect the advisory opinion." For his part, Boris Tadić, the Serbian president, warned that "If the International Court of Justice sets a new principle, it would trigger a process that would create several new countries and destabilise numerous regions in the world."[100]

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.