Loading AI tools

Musical work by Johann Sebastian Bach From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Art of Fugue, or The Art of the Fugue (German: Die Kunst der Fuge), BWV 1080, is an incomplete musical work of unspecified instrumentation by Johann Sebastian Bach. Written in the last decade of his life, The Art of Fugue is the culmination of Bach's experimentation with monothematic instrumental works.

This work consists of fourteen fugues and four canons in D minor, each using some variation of a single principal subject, and generally ordered to increase in complexity. "The governing idea of the work", as put by Bach specialist Christoph Wolff, "was an exploration in depth of the contrapuntal possibilities inherent in a single musical subject."[1] The word "contrapunctus" is often used for each fugue.

The earliest extant source of the work is an autograph manuscript possibly written from 1740 to 1746, usually referred to by its call number as Mus. ms. autogr. P 200 in the Berlin State Library. Bearing the title Die / Kunst der Fuga [sic] / di Sig[nore] Joh. Seb. Bach, which was written by Bach's son-in-law Johann Christoph Altnickol, followed by (in eigenhändiger Partitur) written by Georg Poelchau, the autograph contains twelve untitled fugues and two canons arranged in a different order than in the first printed edition, with the absence of Contrapunctus 4, Fuga a 2 clav (two-keyboard version of Contrapunctus 13), Canon alla decima, and Canon alla duodecima.

The autograph manuscript presents the then-untitled Contrapuncti and canons in the following order: [Contrapunctus 1], [Contrapunctus 3], [Contrapunctus 2], [Contrapunctus 5], [Contrapunctus 9], an early version of [Contrapunctus 10], [Contrapunctus 6], [Contrapunctus 7], Canon in Hypodiapason with its two-stave solution Resolutio Canonis (entitled Canon alla Ottava in the first printed edition), [Contrapunctus 8], [Contrapunctus 11], Canon in Hypodiatesseron, al roversio [sic] e per augmentationem, perpetuus presented in two staves and then on one, [Contrapunctus 12] with the inversus form of the fugue written directly below the rectus form, [Contrapunctus 13] with the same rectus–inversus format, and a two-stave Canon al roverscio et per augmentationem—a second version of Canon in Hypodiatesseron.

Bundled with the primary autograph are three supplementary manuscripts, each affixed to a composition that would appear in the first printed edition. Referred to as Mus. ms. autogr. P 200/Beilage 1, Mus. ms. autogr. P 200/Beilage 2, and Mus. ms. autogr. P 200/Beilage 3, they are written under the title Die Kunst / der Fuga / von J.S.B.

Mus. ms. autogr. P 200, Beilage 1 contains a final preparatory revision of the Canon in Hypodiatesseron, under the title Canon p[er] Augmentationem contrario Motu crossed out. The manuscript contains line break and page break information for the engraving process, most of which was transcribed in the first printed edition. Written on the top region of the manuscript is a note written by Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach:

N.B. Der seel. Papa hat auf die Platte diesen Titul stechen lassen, Canon per Augment: in Contrapuncto all octava, er hat es aber wieder ausgestrichen auf der Probe Platte und gesetzet wie forn stehet N.B. The late father had written on the copper plate the following title, Canon per Augment: in Contrapuncto all octava, but had struck it out again on the proof sheet and restored the title as it was formerly

Mus. ms. autogr. P 200, Beilage 2 contains two-keyboard arrangements of Contrapunctus 13 inversus and rectus, entitled Fuga a 2. Clav: and Alio modo Fuga a 2 Clav. in the first printed edition respectively. Like Beilage 1, the manuscript served as a preparatory edition for the first printed edition.

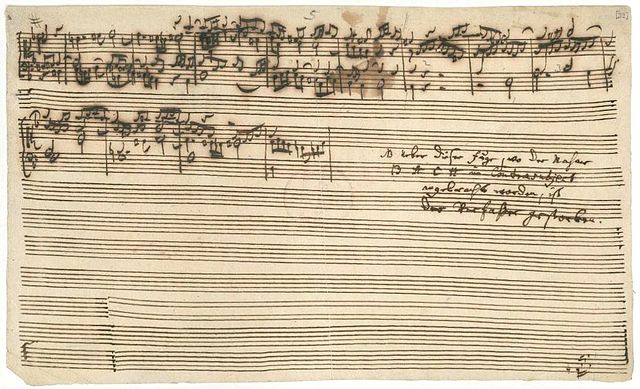

Mus. ms. autogr. P 200, Beilage 3 contains a fragment of a three-subject fugue, which would be later called Fuga a 3 Soggetti in the first printed edition. Unlike the fugues written in the primary autograph, the Fuga is presented in a two-stave keyboard system, instead of with individual staves for each voice. The fugue abruptly breaks off on the fifth page, specifically on the 239th measure and ends with the note written by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: "Ueber dieser Fuge, wo der Nahme BACH im Contrasubject angebracht worden, ist der Verfasser gestorben." ("At the point where the composer introduces the name BACH [for which the English notation would be B♭–A–C–B♮] in the countersubject to this fugue, the composer died.") The following page contains a list of errata by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach for the first printed edition (pages 21–35).

The first printed version was published under the title Die / Kunst der Fuge / durch / Herrn Johann Sebastian Bach / ehemahligen Capellmeister und Musikdirector zu Leipzig in May 1751, slightly less than a year after Bach's death. In addition to changes in the order, notation, and material of pieces which appeared in the autograph, it contained two new fugues, two new canons, and three pieces of ostensibly spurious inclusion. A second edition was published in 1752, but differed only in its addition of a preface by Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg.

In spite of its revisions, the printed edition of 1751 contained a number of glaring editorial errors. The majority of these may be attributed to Bach's relatively sudden death in the midst of publication. Three pieces were included that do not appear to have been part of Bach's intended order: an unrevised (and thus redundant) version of the second double fugue, Contrapunctus X; a two-keyboard arrangement[2] of the first mirror fugue, Contrapunctus XIII; and an organ chorale prelude on "Vor deinen Thron tret ich hiermit" ("Herewith I come before Thy Throne"), derived from BWV 668a, and noted in the introduction to the edition as a recompense for the work's incompleteness, having purportedly been dictated by Bach on his deathbed.

The anomalous character of the published order and the Unfinished Fugue, have engendered a wide variety of theories which attempt to restore the work to the state originally intended by Bach.

The Art of Fugue is based on a single subject, which each canon and fugue employs in some variation:

The work divides into seven groups, according to each piece's prevailing contrapuntal device; in both editions, these groups and their respective components are generally ordered to increase in complexity. In the order in which they occur in the printed edition of 1751 (without the aforementioned works of spurious inclusion), the groups, and their components are as follows.

Simple fugues:

Stretto-fugues (counter-fugues), in which the subject is used simultaneously in regular, inverted, augmented, and diminished forms:

Double and triple fugues, employing two and three subjects respectively:

Mirror fugues, in which a piece is notated once and then with voices and counterpoint completely inverted, without violating contrapuntal rules or musicality:

Canons, labeled by interval and technique:

Alternate variants and arrangements:

Incomplete fugue:

Both editions of the Art of Fugue are written in open score, where each voice is written on its own staff. This has led some to conclude[5] that the Art of Fugue was intended as an intellectual exercise, meant to be studied more than heard. The renowned keyboardist Gustav Leonhardt argued that the Art of Fugue was intended[6] to be played on a keyboard instrument, and specifically the harpsichord. Leonhardt's arguments included the following:[7]

It is now generally accepted by scholars that the work was envisioned for keyboard.[8]

Fuga a 3 Soggetti ("fugue in three subjects"), also called the "Unfinished Fugue" and Contrapunctus 14, was contained in a handwritten manuscript bundled with the autograph manuscript Mus. ms. autogr. P 200. It breaks off abruptly in the middle of its third section, with an only partially written measure 239. This autograph carries a note in the handwriting of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, stating "Über dieser Fuge, wo der Name B A C H im Contrasubject angebracht worden, ist der Verfasser gestorben." ("While working on this fugue, which introduces the name BACH [for which the English notation would be B♭–A–C–B♮] in the countersubject, the composer died.") This account is disputed by modern scholars, as the manuscript is clearly written in Bach's own hand, and thus dates to a time before his deteriorating health and vision would have prevented his ability to write, probably 1748–1749.[9]

Several musicians and musicologists have composed conjectural completions of Contrapunctus XIV which include the fourth subject, including musicologists Donald Tovey (1931), Zoltán Göncz (1992), Yngve Jan Trede (1995), and Thomas Daniel (2010), organists Helmut Walcha,[10] David Goode, Lionel Rogg, and Davitt Moroney (1989), conductor Rudolf Barshai (2010)[11] and Daniil Trifonov (2021). Ferruccio Busoni's Fantasia contrappuntistica is based on Contrapunctus XIV, but it develops Bach's ideas to Busoni's own purposes in Busoni's musical style, rather than working out Bach's thoughts as Bach himself might have done.[12]

Loïc Sylvestre and Marco Costa reported a mathematical architecture of The Art of Fugue, based on bar counts, which shows that the whole work could have been conceived on the basis of the Fibonacci series and the golden ratio.[13]

Dominic Florence proposes that a concept he calls "opposition" governs all the methods that Bach uses in Contrapuncti 1, 2, 3, and 5 to create variety. These include changes in "melody (contrary motion), polyphony (contrapuntal inversion), harmony (dissonance), [rhythmic] density (texture), rhythm (syncopation), and tonality (modulation}".[14] For example, Contrapuncti 1 and 2 both switch repeatedly between the keys of A minor and D minor; Contrapuncti 2 and 3 in addition enter F major and G minor, Contrapunctus 2 also visiting B-flat major once in a further "tonal remove": all three begin and end in D minor. He concludes that "Analyses of fugues should focus on continuous, dynamic, organic processes that evolve over time, rather than on the static and discontinuous dismemberment into strictly delineated sections."[14]

In 1984, the German musicologist Hans Heinrich Eggebrecht suggested a possible religious interpretation of The Art of Fugue, which he agreed was impossible to prove: that the work illustrated in musical terms the Christian doctrine of redemption by God's grace alone, sola gratia, rather than by any action an individual can take. Eggebrecht noted the presence in fugue 3 of the presence of the composer's surname Bach in its theme, the sequence of notes B-A-C-H-C#-D. In Eggebrecht's view, this could mean that the composer is not just signing the work, but is placing himself by his grave, accepting sola gratia as he reaches towards the tonic note, which marks the end of the fugue and symbolically the end of his life. Further, the six-note fragment is chromatic, denoting sinful humanity, whereas the work as a whole is diatonic, symbolising God's perfection.[15]

The Russian musicologist Anatoly Milka suggests that the various numbers embedded in the work have a numerological significance related to the Book of Revelation, the last book of the Bible which describes the apocalypse.[15]

| Number | Use in The Art of Fugue | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 14 | 14 fugues (basic structure of the work) | The surname BACH, taking A=1, B=2, C=3, H=8; a symbol of Christ's cross (lines B---C intersecting A------H). These digits sum to 14. |

| 7 | Two blocks of 7 fugues (according to Milka) | 7 seals = 4 Horsemen of the Apocalypse + 3 calamities, or 7 trumpets = 4 plagues + 3 woes |

| 4 | 4 canons; fugues in each block in groups of 4 and 3 | 4 beasts in Revelation chapter 4 (animals of the 4 evangelists); see also the 4+3 symbolism above |

| 3 | Fugues in groups of 4 and 3 | See the 4+3 symbolism above |

In her 2007 doctoral thesis about the unfinished ending of Contrapunctus 14, the New Zealand organist and conductor Indra Hughes proposed that the work was left unfinished not because Bach died, but as a deliberate choice by Bach to encourage independent efforts at a completion.[16][17]

Douglas Hofstadter's book Gödel, Escher, Bach discusses the unfinished fugue and Bach's supposed death during composition as a tongue-in-cheek illustration of the Austrian logician Kurt Gödel's first incompleteness theorem. According to Gödel, the very power of a "sufficiently powerful" formal mathematical system can be exploited to "undermine" the system, by leading to statements that assert such things as "I cannot be proven in this system". In Hofstadter's discussion, Bach's great compositional talent is used as a metaphor for a "sufficiently powerful" formal system; however, Bach's insertion of his own name "in code" into the fugue is not, even metaphorically, a case of Gödelian self-reference; and Bach's failure to finish his self-referential fugue serves as a metaphor for the unprovability of the Gödelian assertion, and thus for the incompleteness of the formal system.[18]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.