Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

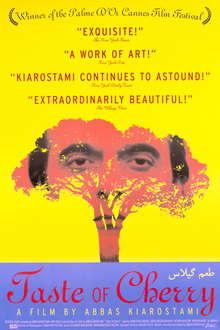

Taste of Cherry

1997 Iranian film directed by Abbas Kiarostami From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Taste of Cherry (Persian: طعم گیلاس..., Ta’m-e gīlās...) is a 1997 Iranian minimalist drama film written, produced, edited, and directed by Abbas Kiarostami, and starring Homayoun Ershadi as a middle-aged Tehran man who drives through a city suburb in search of someone willing to carry out the task of burying him after he commits suicide. The film won the Palme d'Or at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival, which it shared with The Eel.

Remove ads

Plot

Summarize

Perspective

Badii, a middle-aged man, drives through Tehran looking for someone to do a job for him, for which he offers a large sum of money. During his drives with prospective candidates, Badii reveals that he plans to kill himself and has already dug the grave. He tells the people he is soliciting to go to the spot he has chosen the next morning, and either help him up if he has chosen to live or bury him if he has chosen to die. He does not discuss why he wants to commit suicide.

His first recruit is a young, shy Kurdish soldier who refuses to do the job and flees from Badii's car. His second recruit is an Afghan seminarist who also declines because he has religious objections to suicide. The third is Bagheri, an Azeri taxidermist. He is willing to help Badii because he needs the money for his sick child. He tries to convince Badii not to commit suicide and reveals that he too wanted to commit suicide in 1960 but chose to live when, after failing in his attempt, he tasted mulberries which dropped from a tree. Bagheri reveals that he then went home with the mulberries and gave them to his wife, who enjoyed them. He continues to discuss what he perceives to be the beauty of life, including sunrises, the moon, and stars. Bagheri promises to throw dirt on Badii if he finds him dead in the morning. Badii drops him back at his workplace but suddenly runs back to meet him, requesting that in the morning Bagheri should confirm if he is actually dead by throwing some stones at him and jolting him awake in case he is asleep.

That night, Badii lies in his grave while a thunderstorm begins. After a long blackout, the film ends by breaking the fourth wall with camcorder footage of Kiarostami and the film crew filming Taste of Cherry, leaving Badii's choice unknown.

Remove ads

Cast

- Homayoun Ershadi as Mr. Badii

- Abdolrahman Bagheri as Mr. Bagheri, the taxidermist

- Afshin Khorshid Bakhtiari as Worker

- Safar Ali Moradi as Soldier

- Mir Hossein Noori as Seminarian

Style

The film is minimalist in that it is shot primarily with long takes; the pace is leisurely and there are long periods of ambient (background) sound, which the closing sequence shows the crew recording. Mr. Badii is rarely shown in the same shot as the person he is talking to (this is partly because during the filming, director Kiarostami was sitting in the car's passenger seat).[citation needed]

Music

The film does not include a background score, except for the ending titles. This features a trumpet piece, Louis Armstrong's 1929 adaptation of "St. James Infirmary Blues". The only other song featured in the film is "Khuda Bowad Yaret" (May God be your protector) by Afghan singer Ahmad Zaher, which is played in the background on a radio about 38 minutes into the film. [citation needed] In the sequences filmed around and inside the wildlife museum, the background music features the voice of Abdolhossein Mokhtabad.

Remove ads

Release

Summarize

Perspective

Taste of Cherry was awarded the prestigious Palme d'Or at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival in the year of its release,[1] tied with Shohei Imamura's The Eel.

Reception

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 83% based on 40 reviews, with the "critics consensus" reading, "Taste of Cherry's somewhat simple aesthetic belies a richly ambiguous character study with an impressively ambitious thematic scale."[2] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 80 out of 100, based on 22 critics, indicating "generally favorable" reviews.[3] Rob Aldam of Backseat Mafia described the film as "an assured and studied meditation on the question of whether life is worth living".[4] Matthew Lucas of From the Front Row wrote:[5]

"The ending is ambiguous in the most lovely Kiarostami tradition, but its segue into behind the scenes footage is as exhilarating as it is disorienting. It's as if the film is on the verge of revealing all the answers of life itself, and then pulls back at the last second, returning the mystery to the audience. In doing so it attains a kind of haunting mysticism, profoundly shifting the audience's perception of reality. It's Kiarostami's finest work, and one of the best films of the 1990s."

Stephen Holden of The New York Times called the film "simultaneously epic and precisely minuscule", writing that "it isn't until Badii meets the taxidermist that the film finds a lyrical voice to match its powerful visual imagery. His gorgeous, rough-hewn soliloquy about regaining his zest for life after trying to hang himself from a mulberry tree is a simple, eloquent parable of the senses opening to the refreshment of life's simple pleasures."[6] According to Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic, "As the film's design becomes clear to us, a quiet spaciousness begins to inhabit it."[7]

Of the minority of negative reviews, Roger Ebert's in The Chicago Sun-Times was the most scathing, giving the film 1 out of 4 stars. Ebert dismissed the film as "excruciatingly boring" and added,[8]

"I understand intellectually what Kiarostami is doing. I am not impatiently asking for action or incident. What I do feel, however, is that Kiarostami's style here is an affectation; the subject matter does not make it necessary, and is not benefited by it. If we're to feel sympathy for Badhi, wouldn't it help to know more about him? To know, in fact, anything at all about him? What purpose does it serve to suggest at first he may be a homosexual? (Not what purpose for the audience--what purpose for Badhi himself? Surely he must be aware his intentions are being misinterpreted.) And why must we see Kiarostami's camera crew--a tiresome distancing strategy to remind us we are seeing a movie? If there is one thing Taste of Cherry does not need, it is such a reminder: The film is such a lifeless drone that we experience it only as a movie."

Ebert later went on to add the film to a list of his most hated movies of all time.[9]

In his own review of Kiarostami's film, critic Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader awarded it a full four stars. Responding to Ebert's criticisms, Rosenbaum wrote:[10]

"A colleague who finds Taste of Cherry "excruciatingly boring" objects in particular to the fact that we don’t know anything about Badii, to what he sees as the distracting suggestion that Badii might be a homosexual looking for sex, and to what he sees as the tired "distancing strategy" of reminding us at the end that we’re seeing a movie. From the perspective of the history of commercial Western cinema, he has a point on all three counts. But Kiarostami couldn’t care less about conforming to that perspective, and given what he can do, I can’t think of any reason he should care... the most important thing about the joyful finale is that it’s the precise opposite of a "distancing effect". It does invite us into the laboratory from which the film sprang and places us on an equal footing with the filmmaker, yet it does this in a spirit of collective euphoria, suddenly liberating us from the oppressive solitude and darkness of Badii alone in his grave... Kiarostami is representing life in all its rich complexity, reconfiguring elements from the preceding 80-odd minutes in video to clarify what’s real and what’s concocted... Far from affirming that Taste of Cherry is "only" a movie, this wonderful ending is saying, among other things, that it’s also a movie."

Since the film's release, multiple other critics have also declared it a masterpiece; in the British Film Institute's 2012 Sight & Sound poll, six critics and two directors named Taste of Cherry one of the 10 best films ever made.[11] It was also named the 9th best film of the 90s by Slant Magazine. About the ending and its detractors, Calum Marsh wrote:[12]

"It’s baffling that anybody anywhere could watch Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry, love it enthusiastically, and then suggest that its life-affirming pomo coda be excised, as throngs of broadsheet admirers did after the film’s premiere at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival (even more perplexingly, Kiarostami actually heeded their advice, lopping off the ending for its theatrical run in Italy). Those precious final moments—a meta-textual break from the action, shot on video, in which the cast and crew are shown preparing a scene from the film to the sounds of "St. James Infirmary"—are a grand and graceful move beyond the text of both film and life, a liberation from a hero’s grave and a narrative’s closure. That’s where the long journey into night and death bring us: We awaken in daylight, outside the world of the film, rejoicing in the action of cinema. It undercuts nothing; it expands on, enriches, enlivens all that came before it. It’s the ultimate coup: A few minutes of Handycam video transform a very good film about death into a great film about life. "

Home media

On June 1, 1999, The Criterion Collection released the film onto DVD. On July 21, 2020, Criterion released the film on Blu-ray with a new 4K restoration.[13]

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads