Tagalog grammar

Grammar of the Tagalog language From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Tagalog grammar (Tagalog: Balarilà ng Tagalog) are the rules that describe the structure of expressions in the Tagalog language, one of the languages in the Philippines.

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

In Tagalog, there are nine parts of speech: nouns (pangngalan), pronouns (panghalíp), verbs (pandiwà), adverbs (pang-abay), adjectives (pang-urì), prepositions (pang-ukol), conjunctions (pangatníg), ligatures (pang-angkóp) and particles.

Tagalog is an agglutinative yet slightly inflected language.

Pronouns are inflected for number and verbs for focus/voice and aspect.

Verbs

Summarize

Perspective

Tagalog verbs are complex and are changed by taking on many affixes reflecting focus/trigger, aspect and mood. Below is a chart of the main verbal affixes, which consist of a variety of prefixes, suffixes, infixes, and circumfixes.

Conventions used in the chart:

- CV~ stands for reduplication of the first syllable of a root word; that is, the first consonant (if any) and the first vowel of the word.

- N stands for a nasal consonant, which are m, n, or ng.

- m is used when the prefixed word starts with the consonants b or p

- n is used before the consonants d, t, and l

- in all other cases, ng /ŋ/ is used

- ∅ means that the verb root is used, therefore no affixes are added.

- Punctuation marks indicate the type of affix a particular bound morpheme is:

- hyphens mark prefixes if placed after the morpheme (e.g., mag-), or suffixes if placed before it (e.g., -han)

- ⟨⟩ marks infixes, which is typically placed before the first vowel of the word, and after the first consonant if there is any. Thus, the word "sumulat" (s⟨um⟩ulat) is composed of the root word sulat and the infix ⟨um⟩.

- ~ is used to separate the reduplicated morpheme (CV), from the root word, such that "susulat" is written as (su~sulat) and "sumusulat" as (s⟨um⟩u~sulat).

| Complete | Progressive | Contemplative | Infinitive | Imperative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actor trigger I | ⟨um⟩ bumasa |

C⟨um⟩V~ bumabasa |

CV~ babasa |

⟨um⟩ bumasa |

∅ |

| Actor trigger II | nag- nagbasa |

nag-CV~ nagbabasa |

mag-CV~ magbabasa |

mag- magbasa |

pag- pagbasa |

| Actor trigger III | na- nabasa |

na-CV~ nababasa |

ma-CV~ mababasa |

ma- mabasa |

pa- pabasa |

| Actor trigger IV | naN- (nang-, nam-, nan-) nangbasa (nambasa) |

naN-CV~ nangbabasa (nambabasa) |

maN-CV~ mangbabasa (mambabasa) |

maN- mangbasa (mambasa) |

paN- pangbasa (pambasa) |

| Object trigger I | ⟨in⟩ binasa |

C⟨in⟩V~ binabasa |

CV~ ... -(h)in babasahin |

-(h)in basahin |

-a (or verb root) basa |

| Object trigger II | i⟨in⟩- ibinasa |

i-C⟨in⟩V~ ibinabasa |

i-CV~ ibabasa |

i- ibasa |

-(h)an/-(h)in basaan |

| Object trigger III | ⟨in⟩ ... -(h)an binasahan |

C⟨in⟩V~ ... -(h)an binabasahan |

CV~ ... -(h)an babasahan |

-(h)an basahan |

-(h)i basahi |

| Locative trigger | ⟨in⟩ ... -(h)an binasahan |

C⟨in⟩V~ ... -(h)an binabasahan |

CV~ ... -(h)an babasahan |

-(h)an basahan |

∅ |

| Benefactive trigger | i⟨in⟩- ibinasa |

i-C⟨in⟩V~ ibinabasa |

i-CV~ ibabasa |

i- ibasa |

∅ |

| Instrument trigger | ip⟨in⟩aN- ipinambasa |

ip⟨in⟩aN-CV~ ipinambabasa |

ipaN-CV~ ipambabasa |

ipaN- ipambasa |

∅ |

| Reason trigger | ik⟨in⟩a- ikinabasa |

ik⟨in⟩a-CV~ ikinababasa |

ika-CV~ ikababasa |

ika- ikabasa |

∅ |

With object-focus verbs in the completed and progressive aspects, the infix -in- frequently becomes the prefix ni- if the root word begins with /l/, /r/, /w/, or /j/; e.g., linalapitan or nilalapitan and inilagáy or ilinagáy.

When suffixing -in and -an to a word that ends in a vowel, an epenthetic h is inserted. This helps to distinguish them from words that have a glottal stop, which is usually not written except when diacritical marks are applied, such that "basa" (to read) becomes "basahin" while "basa" (to be wet, otherwise spelt as "basâ") becomes "basaín" pronounced with a glottal stop.

The imperative affixes are not often used in Manila, but they do exist in other Tagalog speaking provinces.

Archaic Forms

| Complete | Progressive | Contemplative | Infinitive | Imperative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archaic Actor trigger I (Unassimilated) |

⟨ungm⟩ or ⟨ingm⟩ bungmasa, tingmingin |

C⟨ungm⟩V~ or C⟨ingm⟩V~ bungmabasa, tingmitingin |

CV~ babasa |

⟨um⟩ bumasa |

∅ |

| Archaic Actor trigger I (Assimilated) |

b/p → n nasa |

b/p → n + REDUP nanasa |

b/p → m + REDUP mamasa |

b/p → m masa |

∅ |

In old Tagalog, the complete and progressive aspects of actor trigger I was marked with the affix "-ungm-" or "-ingm-', while "-um-" was used solely as the infinitive form. The rule is that when a verb has an "i" in its initial syllable, the infix used is "-ingm-" like "tingmingin" (looked, complete aspect) and "tingmitingin" (is looking, progressive aspect), otherwise "-ungm-" is used. This is a case called vowel harmony. Another archaic feature is when a verb starts in a "b" or "p", which becomes an "n" for the complete and progressive aspects, and "m" for contemplative and infinitive. The word "pasok" (to enter) therefore becomes "nasok" (complete), "nanasok" (progressive), "mamasok" (contemplative), and "masok" (infinitive). Though these have been lost in the Manila dialect, they are preserved in some Tagalog dialects. The allophones "d" and "r" are still somewhat preserved when it comes to verbs like "dating (to arrive)" but it is sometimes ignored.

Trigger

The central feature of verbs in Tagalog and other Philippine languages is the trigger system, often called voice or focus.[1] In this system, the thematic relation (agent, patient, or other oblique relations – location, direction, etc.) of the noun marked by the direct-case particle is encoded in the verb.

Actor trigger forms

Also known as the agent trigger, agent focus, actor focus, or by the abbreviations AT or AF. This verb form triggers a reading of the direct noun (marked by "ang") as the agent of the clause. The main affixes/forms under this trigger are -um-, mag-, ma-, and mang-; while their derivatives (e.g., maka-, ma- -an, magsi-, etc.) may also function as actor focus.

Some verb roots only take one of the main affixes to form the actor trigger of that verb, such as "tingín" (to look) which only uses the -um- conjugation as its actor trigger form. Other root words may take two or more, such as "sulat" (to write) which could take mag- and -um- conjugations. In such instances, the different verb forms may have the same exact meaning, or they may have some slight nuances. In the case of "sulat", "magsulat" is closer to the meaning of physically writing a letter, while "sumulat" is closer to the meaning of sending a letter out.[2] "sayáw" (to dance), on the other hand, has "sumayáw" and "magsayáw" which mean the same thing. Furthermore, there are a few root verbs that derive opposite meanings through these affixes, such as in the case of "bilí" (to buy), where "bumilí" means to buy and "magbilí" is to sell.

The difference between these four actor trigger forms are complicated and there seems to be no consistent rule dictating when one form should be used over another. That said, memorizing what affixes a verb root uses and its corresponding meaning is essential in learning Tagalog.

- ma- is only used with a few roots which are semantically intransitive, for example, matulog (to sleep) and maligò (to bathe). Ma- is not to be confused with ma-, a patient-trigger prefix verb form.

Object trigger forms

Otherwise known as the patient trigger, patient focus, object focus, or by its initials OT, OF, PT, or PF. This verb form triggers a reading of the direct noun (marked by "ang") as the patient of the clause. There are three main affixes/forms used in this trigger, -in-, i-, and -an:

- -in is the most commonly used patient trigger form. It is generally used with:

- actions that involve movement towards the agent: kainin (to eat something), bilhín (to buy something).

- actions that involve permanent change: basagin (to crack something), patayín (to kill something).

- actions that involve thought: isipin (to think of something), alalahanin (to remember something).

- i- is also a benefactive trigger, but when used as an object trigger, it denotes actions which involve something that is moved away from an agent: ibigáy (to give something), ilagáy (to put something), itaním (to plant something).

- -an can also serve as a locative or benefactive trigger, but as an object trigger, it denotes actions involving a surface change (doing unto something): hugasan (to rinse something), walisán (to sweep something off), sulatan (to write on a surface).

Affixes can also be used in nouns or adjectives: baligtarán (from baligtád, to reverse) (reversible), katamarán (from tamád, lazy) (laziness), kasabihán (from sabi, to say) (proverb), kasagutan (from sagót, answer), bayarín (from bayad, to pay) (payment), bukirín (from bukid, farm), lupaín (from lupà, land), pagkakaroón (from doón/roón, there) (having/appearance), and pagdárasál (from dasál, prayer). Verbs with affixes (mostly suffixes) are also used as nouns, which are differentiated by stress position. Examples are panoórin (to watch or view) and panoorín (materials to be watched or viewed), hangarín (to wish) and hangárin (goal/objective), arálin (to study) and aralín (studies), and bayáran (to pay) and bayarán (someone or something for hire).

List of triggers and examples

The actor trigger marks the direct noun as the agent (doer) of the action:

- Bumilí ng saging ang lalaki sa tindahan para sa unggóy.

- The man bought a banana at the store for the monkey.

The object trigger marks the direct noun as the patient (receiver) of the action:

- Binilí ng lalaki ang saging sa tindahan para sa unggóy.

- The man bought the banana at the store for the monkey.

The locative trigger marks the direct noun as the location or direction of an action or the area affected by the action.

- The man bought a banana at/from the store.

- Binilhán ng lalaki ng saging ang tindahan. (formal/dated form)

- Pinagbilhán ng lalaki ng saging ang tindahan. (colloquial form)

The benefactive trigger marks the direct noun as the person or thing that benefits from the action; i.e., the beneficiary of an action.

- The man bought a banana for the monkey.

- Ibinilí ng lalaki ng saging ang unggóy. (formal/dated form)

- Binilhán ng lalaki ng saging ang unggóy. (colloquial form)

The instrumental trigger marks the direct noun as the means by which the action is performed.

- Ipinambilí ng lalaki ng saging ang pera ng asawa niyá.

- The man bought a banana with his spouse's money.

The reason trigger marks the direct noun as the cause or reason why an action is performed. It is mostly used exclusively with verbs of emotion.

- Ikinagulat ng lalaki ang pagdatíng ng unggóy.

- The man got surprised because of the monkey's arrival.

Aspect

The aspect of the verb indicates the progressiveness of the verb. It specifies whether the action happened, is happening, or will happen. Tagalog verbs are conjugated for time using aspect rather than tense, which can be easily expressed with phrases and time prepositions.[3][4]

| Aspect | Use | Example sentence | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completed (Perfective) | indicates that the action has been completed | Naglutò ang babae | The woman cooked |

| Naglutò na ang babae | The woman has/had cooked | ||

| Uncompleted (Imperfective) | indicates that the action has started, but not completed and is ongoing; also indicates habitual actions and general facts | Naglulutò ang babae | The woman cooks |

| Naglulutò na ang babae | The woman is (already) cooking | ||

| Naglulutò pa ang babae | The woman is (still) cooking | ||

| Unstarted (Contemplative) | indicates that the action has not been started | Maglulutò ang babae | The woman will cook |

| Maglulutò na ang babae | The woman is going to cook (now) | ||

| Maglulutò pa ang babae | The woman is yet to cook | ||

| Recently completed | indicates that the action has been completed just before the time of speaking or just before some other specified time | Kalulutò lang ng babae | The woman has just cooked |

Infinitive (Pawatas)

This serves as the base form of the verb, and is not marked by aspect. It is typically used in modal and subjunctive constructions. It is also used in standard Tagalog as the basis for the imperative form of the verb, by adding a second-person pronoun, such as ka/mo (you) and kayó/ninyó (you all), directly after it.

This is formed by affixing a verbal trigger suffix to the root word.

| Root Word | Affix | Base Form | Trigger |

|---|---|---|---|

| alís (leave) | -um- | umalís (to leave) | Actor trigger I |

| kain (eat) | -um- | kumain (to eat) | Actor trigger I |

| sulat (write) | mag- | magsulát (to write) | Actor trigger II |

| tulog (sleep) | ma- | matulog (to sleep) | Actor trigger III |

| hingî (ask/request) | mang- | manghingî (to ask/request) | Actor trigger IV |

| alís (leave) | -(h)in | alisín (to remove) | Object trigger I |

| basa (read) | -(h)in | basahin (to read) | Object trigger I |

| bigáy (give) | i- | ibigáy(to give) | Object trigger II |

| bilí (buy) | -(h)an | bilhán (to buy from) | Locative trigger |

| balík (return) | i- | ibalík (to bring back) | Benefactive trigger |

| hugas (wash) | ipang- | ipanghugas (to use for washing) | Instrumental trigger |

| galák (joy) | ika- | ikagalák (to bring joy) | Reason trigger |

Examples of infinitive use in modal sentences:

| Grammatical mood | Example | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Subjunctive | dapat matulog ka | you should sleep |

| Optative | sana ibigáy mo | I hope you will give (it) |

| Necessitative | kailangan niláng kumain | they need to eat |

| Imperative | basahin mo na | read it now |

| Prohibitive | huwág kang manghingî ng tawad | don't ask for forgiveness |

Perfective (Naganáp)

Also known as the complete or completed aspect. This implies that the action was done in the past, prior to the time of speaking or some other specified time. This aspect is characterized by:

- the use of the infix -in- in all triggers except the actor trigger

- the alteration of initial m to n in mag-, ma-, and mang- (actor triggers II, III, and IV)

- no change with -um- (actor trigger I)

In the complete aspect of the object trigger -in, that suffix -in (or -hin) is removed. This is in contrast with other triggers where the trigger affix remains.

| Root Word | Trigger | Base Form | Affix | Complete Aspect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| alís (leave) | Actor trigger I | umalís (to leave) | no change | umalís (left) |

| kain (eat) | Actor trigger I | kumain (to eat) | no change | kumain (ate) |

| sulat (write) | Actor trigger II | magsulat (to write) | mag- → nag- | nagsulat (wrote) |

| tulog (sleep) | Actor trigger III | matulog (to sleep) | ma- → na- | natulog (slept) |

| hingî (ask/request) | Actor trigger IV | manghingî (to ask/request) | mang- → nang- | nanghingî (asked/requested) |

| alís (leave) | Object trigger I | alisín (to remove) | remove -in + add -in- | inalís (removed) |

| basa (read) | Object trigger I | basahin (to read) | remove -hin + add -in- | binasa (read) |

| bigáy (give) | Object trigger II | ibigáy(to give) | add -in- | ibinigáy (given) |

| bilí (buy) | Locative trigger | bilhán (to buy from) | add -in- | binilhán (bought from) |

| balík (return) | Benefactive trigger | ibalík (to bring back) | add -in- | ibinalík (brought back) |

| hugas (wash) | Instrumental trigger | ipanghugas (to use for washing) | add -in- | ipinanghugas (used for washing) |

| galák (joy) | Reason trigger | ikagalák (to bring joy) | add -in- | ikinagalák (brought joy) |

On its own, the perfective verb may not necessarily imply that the action is completed. Adding the particle na directly after it strengthens the notion that it is in fact completed. Compare this with the difference between English simple past and past perfect tenses.

| Without particle | With particle | |

|---|---|---|

| Example | pumuntá akó sa Baguio pagdatíng nilá | pumuntá na akó sa Baguio pagdatíng nilá |

| Meaning | I went to Baguio when they came | I have (already) gone to Baguio when they came |

Imperfective (Nagaganap)

Also known as the progressive or uncompleted aspect. This implies that the action has started, is ongoing, and not yet completed. It is also used with habitual actions, or actions that signify general facts. This aspect is characterized by the reduplication of the first syllable of the root word, followed by application of the same morphological rules as seen with the complete aspect. If the base form of the verb has its stress on the last syllable, a secondary stress usually falls on the reduplicated syllable.

| Root Word | Trigger | Base Form | Affix | Complete Aspect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| alís (leave) | Actor trigger I | umalís (to leave) | CV reduplication | umáalís (leaving) |

| kain (eat) | Actor trigger I | kumain (to eat) | CV reduplication | kumakain (eating) |

| sulat (write) | Actor trigger II | magsulát (to write) | CV reduplication + mag- → nag- | nagsúsulát (writing) |

| tulog (sleep) | Actor trigger III | matulog (to sleep) | CV reduplication + ma- → na- | natutulog (sleeping) |

| hingî (ask/request) | Actor trigger IV | manghingî (to ask/request) | CV reduplication + mang- → nang- | nanghíhingì (asking/requesting) |

| alís (leave) | Object trigger I | alisín (to remove) | CV reduplication + remove -in + add -in- | ináalís (removed) |

| basa (read) | Object trigger I | basahin (to read) | CV reduplication + remove -hin + add -in- | binabasa (reading) |

| bigáy (give) | Object trigger II | ibigáy(to give) | CV reduplication + add -in- | ibiníbigáy (giving) |

| bilí (buy) | Locative trigger | bilhán (to buy from) | CV reduplication + add -in- | biníbilhán (buying from) |

| balík (return) | Benefactive trigger | ibalík (to bring back) | CV reduplication + add -in- | ibinábalík (bringing back) |

| hugas (wash) | Instrumental trigger | ipanghugas (to use for washing) | CV reduplication + add -in- | ipinanghuhugas (using for washing) |

| galák (joy) | Reason trigger | ikagalák (to bring joy) | CV reduplication + add -in- | ikinagágalák (bringing joy) |

Contemplative (Magaganap)

This implies that the action has not yet started but anticipated. This aspect is characterized solely by the reduplication of the first syllable of the root word.

In the contemplative aspect of the actor trigger -um-, that infix -um- is removed.

| Root Word | Trigger | Base Form | Affix | Complete Aspect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| alís (leave) | Actor trigger I | umalís (to leave) | remove -um- + CV reduplication | áalís (will leave) |

| kain (eat) | Actor trigger I | kumain (to eat) | remove -um- + CV reduplication | kakain (will eat) |

| sulat (write) | Actor trigger II | magsulat (to write) | CV reduplication | magsúsulát (will write) |

| tulog (sleep) | Actor trigger III | matulog (to sleep) | CV reduplication | matutulog (will sleep) |

| hingî (ask/request) | Actor trigger IV | manghingî (to ask/request) | CV reduplication | manghíhingì (will ask/request) |

| alís (leave) | Object trigger I | alisín (to remove) | CV reduplication | áalisín (will remove) |

| basa (read) | Object trigger I | basahin (to read) | CV reduplication | bábasahin (will read) |

| bigáy (give) | Object trigger II | ibigáy(to give) | CV reduplication | ibíbigáy (will give) |

| bilí (buy) | Locative trigger | bilhán (to buy from) | CV reduplication | bíbilhán (will buy from) |

| balík (return) | Benefactive trigger | ibalík (to bring back) | CV reduplication | ibábalík (will bring back) |

| hugas (wash) | Instrumental trigger | ipanghugas (to use for washing) | CV reduplication | ipanghuhugas (will use for washing) |

| galák (joy) | Reason trigger | ikagalák (to bring joy) | CV reduplication | ikagágalák (will bring joy) |

Recently Complete (Katatapos)

This implies that the action has just been completed before the time of speaking or before a specified time. This aspect is unique in that it does not use the direct case marker ang to mark a focused argument. All nouns bound to a verb in this aspect are only marked by the indirect and oblique markers.

It is often taught that to form this aspect, the first syllable of the word should be reduplicated followed by adding the prefix ka-. In colloquial speech however, the prefix kaka- is used instead without any reduplication. A verb in this aspect is always followed by the particle lang.

| Root Word | Formal | Informal |

|---|---|---|

| alís (leave) | kaáalís (just left) | kakáalís (just left) |

| kain (eat) | kakakain (just ate) | |

| sulat (write) | kasusulat (just wrote) | kakasulat (just wrote) |

| tulog (sleep) | katutulog (just slept) | kakatulog (just slept) |

| hingî (ask/request) | kahíhingî (just asked/requested) | kakahingî (just asked/requested) |

| basa (read) | kababasa (just read) | kakabasa (just read) |

| bigáy (give) | kabíbigáy (just gave) | kakabigáy (just gave) |

| bilí (buy) | kabíbilí (just bought) | kakabilí (just bought) |

| balík (return) | kabábalík (just returned) | kakabalík (just returned) |

| hugas (wash) | kahuhugas (just washed) | kakahugas (just washed) |

Mood

Tagalog verbs also have affixes expressing grammatical mood; some examples are indicative, potential, social, causative and distributed.

Indicative

Nagdalá siyá ng liham.

"(S)he brought a letter."

Bumilí kamí ng bigás sa palengke.

"We bought rice in the market."

Kumain akó.

"I ate."

Hindî siyá nagsásalitâ ng Tagalog.

"(S)he does not speak Tagalog."

Causative magpa-

Nagpadalá siyá ng liham sa kaniyáng iná.

"He sent (literally: caused to be brought) a letter to his mother."

Distributive maN-

Namilí kamí sa palengke.

"We went shopping in the market."

Social maki-

Nakikain akó sa mga kaibigan ko.

"I ate with my friends."

Potential maka-/makapag-

Hindî siyá nakapagsásalitâ ng Tagalog.

"(S)he was not able to speak Tagalog."

Nouns

Summarize

Perspective

While Tagalog nouns are not inflected, they are usually preceded by case-marking particles. These follow an Austronesian alignment, also known as a trigger system, which is a distinct feature of Austronesian languages. There are three basic cases: direct (ang/si); indirect (ng/ni); and oblique (sa/kay).

The direct case marks the noun which has a special relation to the verb in the clause. Here, it is the verb's trigger that determines what semantic role (agent, patient, etc.) the noun is in. The indirect case marks the agent or patient, or both, that isn't marked with the direct case in the clause. The oblique case marks the location, benificiary, instrument, and any other oblique argument that isn't marked with the direct case.

In clauses using the actor trigger, the direct case would mark the agent of the verb (corresponding to the subject in the English active voice), the indirect would mark the patient (direct object), while any other argument would be marked by the oblique case. In the object trigger, the reverse occurs, wherein the direct would mark the patient and the indirect marking the agent. When other verb triggers are used (i.e, locative, beneficiary, instrumental, causal triggers), both agent and patient would be marked by the indirect case, the focused oblique argument marked with the direct case, and any other argument by the oblique case.

One of the functions of trigger in Tagalog is to code definiteness, analogous to the use of definite and indefinite articles (i.e., the & a) in English. That said, an argument marked with the direct case is always definite. Whereas, when a patient argument is marked with the indirect case, it is generally indefinite, but an agent argument marked with the same indirect case would be understood as definite. To make it indefinite, the numeral isá (one) is used.

| Sentence 1 (AF) | Sentence 2 (OF) | Sentence 3 (OF) | Sentence 4 (OF) | Sentence 5 (AF) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tagalog | kumain ang pusà ng isdâ | kinain ng pusa ang isdâ | kinain ng isáng pusà ang isdâ | kinain ng isáng pusà ang isáng isdâ | kumain ang isáng pusà ng isáng isdâ |

| English | the cat ate a fish | the cat ate the fish | a cat ate the fish | a cat ate a fish | a cat ate a fish |

The indirect particle is also used as a genitive marker. It is for this reason that Tagalog lean more towards a VOS word order, as an indirect (ng/ni) argument directly following a direct (ang/si) argument might be misinterpreted as a possessive construction. For instance with the sentence above, kumain ang pusà ng isdâ may be read as "the cat of the fish ate".

The oblique particle and the locative derived from it are similar to prepositions in English, marking things such as location and direction.

The case particles fall into two classes: one used with names of people (proper) and one for everything else (common).

The common indirect marker is spelled ng and pronounced [naŋ]. Mgá, pronounced [maˈŋa], marks the common plural.

Tagalog has associative plural[5] in addition to additive plural.

Cases

| Direct (ang) | Indirect (ng) | Oblique (sa) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common | singular | ang, 'yung (iyong) | ng, nu'ng (niyong) | sa |

| plural | ang mgá, 'yung mgá (iyong mgá) | ng mgá, nu'ng mgá (niyong mgá) | sa mgá | |

| Personal | singular | si | ni | kay |

| plural | sina | nina | kina | |

Common noun affixes

| ka- | indicating a companion or colleague |

| ka- -(h)an | collective or abstract noun |

| pan-, pam-, pang- | denoting instrumental use of the noun |

Examples

ex:

Dumatíng

(has) arrived

ang

the

lalaki.

man

"The man arrived."

ex:

Nakita

saw

ni Juan

by (the) Juan

si María.

(the) María

"Juan saw María."

Note that in Tagalog, even proper nouns require a case marker.

ex:

Pupunta

will go

siná

PL.NOM.ART

Elena

Elena

at

and

Roberto

Roberto

sa

at

bahay

house

ni

of

Miguel.

Miguel

"Elena and Roberto will go to Miguel's house."

ex:

Nasaan

Where

ang mga

the.PL

libró?

book

"Where are the books?"

ex:

Na kay

Is with

Tatay

Father

ang

the

susì.

key

"Father has the key."

ex:

Malusóg

Healthy

ang

(the)

sanggól

baby

niyó.

your(plural)

"Your baby is healthy."

ex:

Para

For

kina

the.PL

Luis

Luis

ang

the

handaan..

party

"The party is for Luis and the others."

Pronouns

Summarize

Perspective

Like nouns, personal pronouns are categorized by case. As above, the indirect forms also function as the genitive.

| Direct (ang) | Indirect (ng) | Oblique (sa) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | singular | akó | ko (nakin) | akin | |

| dual | kitá/kata[6] | nita/nata (ta) [6] | kanitá/kanata (ata)[6] | ||

| plural | inclusive | tayo | natin | atin | |

| exclusive | kamí | namin | amin | ||

| 2nd person | singular | ikáw (ka) | mo (niyo) | iyó | |

| plural | kayó | ninyó | inyó | ||

| 3rd person | singular | siyá | niyá | kaniyá | |

| plural | silá | nilá | kanilá | ||

| Direct second person (ang) with Indirect (ng) first person | |

|---|---|

| (to) you by/from me | kitá[7] |

Pronoun sequences are ko ikáw (kitá), ko kayó, ko siyá, and ko silá.

Examples:

Sumulat akó.

"I wrote."

Sinulatan akó ng liham.

"He/She/They wrote me a letter."

Note: If "ng liham" is removed from the sentence, it becomes "I was written on"

Ibíbigay ko ito sa kaniyá.

"I will give this to him/her/them."

Genitive pronouns follow the word they modify. Oblique pronouns can take the place of the genitive pronoun but they precede the word they modify.

Ang bahay ko.

Ang aking bahay.

"My house."

The inclusive dual pronoun kata/kitá has largely disappeared from the Manila Dialect. It survives in other Tagalog dialects, particularly those spoken in the rural areas. However kitá is used to replace the pronoun sequence [verb] ko ikaw, (I [verb] you).

The 1st–2nd dual pronoun "kata/kitá" referring to "you and I" is traditionally used as follows:

Mágkaibigan kitá. (Manila Dialect: Mágkaibigan tayo.)

"You and I are friends." (Manila Dialect: “We are friends.")

Examples:

Mágkásintahan kitá.(We are lovers.)

Maayós áng bahay nita. (Our house is fixed.)

Magagandá áng mgá paróroonan sá kanitá. (The destinations are beautiful at ours.)

As previously mentioned, the pronoun sequence [verb] ko ikáw, (I [verb] you) may be replaced by kitá.

Mahál kitá.

"I love you."

Bíbigyan kitá ng pera.

"I will give you money."

Nakità kitá sa tindahan kahapon.

"I saw you at the store yesterday."

Kaibigan kitá.

"You are my friend."

The inclusive pronoun tayo refers to the first and second persons. It may also refer to a third person(s).

The exclusive pronoun kamí refers to the first and third persons but excludes the second.

Walâ tayong bigás.

"We (you and me) have no rice."

Walâ kaming bigás.

"We (someone else and me, but not you) have no rice."

The second person singular has two forms. Ikáw is the non-enclitic form while ka is the enclitic which never begins a sentence. The plural form kayó is also used politely in the singular, similar to French vous.

Native nouns are genderless, hence siyá means he, she, or they (singular).

Polite or formal usage

Tagalog, like many languages, marks the T–V distinction: when addressing a single person in polite/formal/respectful settings, pronouns from either the 2nd person plural or the 3rd person plural group are used instead of the singular 2nd person pronoun. They can be used with, or in lieu of, the pô/hô iterations without losing any degree of politeness, formality, or respect:

- ikáw or ka ("you" sgl.) becomes kayó ("you" pl.) or silá ("they")

- mo (post-substantive "your") becomes niyó or ninyó (more polite), (post-substantive "your" pl.) or nilá (post-substantive "their")

- iyó(ng) ("yours" sgl. or pre-substantive "your" sgl.) becomes inyó(ng) ("yours" pl. or pre-substantive "your" pl.) or kanilá(ng) ("theirs" or pre-substantive "their")

Example:

English: "What's your name?"

Casual: Anó'ng pangalan mo?

Respectful: Anó'ng pangalan ninyo? or Anó'ng pangalan nilá?

Using such pluralized pronouns is quite sufficient for expressing politeness, formality or respect, particularly when an affirmative (or negative) pô/hô iteration isn't necessary.

Additionally, the formal second-person pronouns Ikaw (Ka), Kayo, Mo, and Ninyo, third-person forms Niya and Siya, and their oblique forms Inyo, Iyo, and Kaniya are customarily and reverentially capitalized, particularly in most religion-related digital and printed media and their references. Purists who frame this capitalization as nonstandard and inconsistent do not apply it when typing or writing.

Demonstrative pronouns

Tagalog's demonstrative pronouns are as follows.

| Direct (ang) | Indirect (ng) | Oblique (sa) | Locative (nasa) | Existential | Manner (gaya) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest to speaker (this, here)* | iré, aré | niré | díne/ríne | nandine(andine)/nárine | eré | ganiré |

| Near speaker and addressee (this, here) | itó | nitó | díto/ríto | nandíto(andíto)/nárito | éto/héto | ganitó |

| Nearest addressee (that, there) | iyán | niyán | diyán/riyán | nandiyán(andíyan)/náriyan | ayán/hayán | ganiyán |

| Remote (that, there) | iyón, yaón | niyón | doón/roón | nandoón(andoón)/nároon | ayón/hayón | ganoón (gayón/ganó'n)/ garoón |

Notes:

- Although dine and dito both mean here, its difference is the first one pertains to the speaker only while the second one includes the listener. Lost in Standard Filipino/Tagalog (Manila dialect: dito) but still survive in province dialects like Batangas. The same goes for direct, indirect, oblique, locative, existential, and manner (nearest to speaker).

- Yaón is an old-fashioned word which means that.The modern word is iyón.

- The oblique are verbs and locative are pseudo-verbs; for instance, dumito, dumidito, and didito for oblique; and narito, naririto, and nandito for oblique. However, some are archaic and some are old-fashioned.

- Words like pariné, paritó, pariyón, and paroón are combined with pa+(oblique word). These were old-fashioned and/or archaic but still survive in dialects.

- The contractions are: 're, 'to, 'yan, 'yun, n'yan, gan'to, gan'yan, gan're, gano'n (gayon)

*Many Tagalog speakers may use itó in place of iré/aré.

Examples:

|

Anó itó? Sino ang lalaking iyón? Gáling kay Pedro ang liham na itó. |

Nandito akó. Kakain silá roón. Saán ka man naróroon. |

Kumain niyán ang batà. Ayón palá ang salamín mo! Heto isáng regalo para sa iyó. |

Adjectives

Summarize

Perspective

Just like English adjectives, Tagalog adjectives modify a noun or a pronoun.

Forms

Simple (Payák)

These consist of only the root word.

Examples: hinóg (ripe), sabog (exploded), ganda (beautiful)

Affixed (Maylapì)

These consist of the root word and one or more affixes.

Examples: tinanóng (questioned), kumakain (eating), nagmámahál (loving)

Repeating (Inuulit)

These are formed by the repetition of the whole or part of the root word.

Examples: puláng-pulá (really red), putíng-putî (really white), araw-araw (every day), gabí-gabí (every night)

Compound (Tambalan)

These are compound words.

Examples: ngiting-aso (literally: "dog smile", meaning: "big smile"), balát-sibuyas (literally: "onion-skinned", meaning: "crybaby")

Types

Descriptive (Panlarawan)

This states the size, color, form, smell, sound, texture, taste, and shape.

Examples: muntî (little), biluhabà (oval), matamis (sweet), malubhâ (serious)

Proper (Pantangì)

This states a specific noun. This consists of a common noun and a proper noun. The proper noun (that starts with a capital letter) is modifying the type of common noun.

Examples: wikang Ingles (English language), kulturang Espanyol (Spanish culture), pagkaing Iloko (Ilokano food)

Pamilang

This states the number, how many, or a position in order. This has multiple types.

- Sequence (Panunurán) – This states the position in an order. Examples: ikatló (third), una (first), pangalawá (second)

- Quantitative (Patakarán) – This states the actual number. Examples: isa (one), apat (four), limang libo (five thousand)

- Fraction (Pamahagì) – This states a part of a whole. Examples: kalahatì (half), limáng-kawaló (five-eights), sangkapat (fourth)

- Monetary (Pahalagá) – This states a price (equivalent to money) of a thing or any bought item. Examples: piso (one peso), limampung sentimo (fifty centavos), sandaang piso (one hundred pesos)

- Collective (Palansák) – This states a group of people or things. This identifies the number that forms that group. Examples: dalawahan (by two), sampú-sampû (by ten), animan (by six)

- Patakdâ – This states the exact and actual number. This cannot be added or subtracted. Examples: iisa (only one), dadalawa (only two), lilima (only five)

Degrees of Comparison

Just like English adjectives, Tagalog adjectives have 3 degrees of comparison.

Positive (Lantáy)

This only compares one noun/pronoun.

Example: maliít (small), kupas (peeled), matabâ (fat)

Comparative (Pahambíng)

This is used when 2 nouns/pronouns are being compared. This has multiple types.

- Similar (Magkatulad) – This is the comparison when the traits compared are fair. Usually, the prefixes ga-, sing-/kasíng-, and magsing-/magkasíng- are used.

- Dissimilar (Di-magkatulad) – This is the comparison if it shows the idea of disallowance, rejection or opposition.

- Palamáng – the thing that is being compared has a positive trait. The words "higít", "lalo", "mas", "di-hamak" and others are used.

- Pasahol – the thing that is being compared has a negative trait. The words "di-gaano", "di-gasino", "di-masyado" and others are used.

Superlative (Pasukdól)

This is the highest degree of comparison. This can be positive or negative. The prefix "pinaká" and the words "sobra", "ubod", "tunay", "talaga", "saksakan", and "hari ng ___" are used, as well as the repetition of the adjective.

| Positive

(Lantay) |

Comparative (Pahambing) | Superlative

(Pasukdol) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Similar

(Magkatulad) |

Dissimilar (Di-magkatulad) | |||

| Palamáng | Pasahol | |||

| pangit (ugly) | kasíng-pangit (as ugly as) | higít na pangit (uglier) | di-gaanong pangit (not that ugly) | pinakapangit (ugliest) |

| magandá (beautiful) | singgandá (as beautiful as) | mas magandá (more beautiful) | di-masyadong magandá (not that beautiful) | ubod ng gandá (most beautiful) |

| mabangó (fragrant) | magkasíng-bangó (as fragrant as) | lalong mabangó (more fragrant) | di-gasinong mabangó (not that fragrant) | tunay na mabangó (most fragrant) |

Degrees of Description

These degrees have no comparison.

Lantáy

This is when the simple/plain form of the adjective is being used for description.

Examples: matalino (smart), palatawá (risible)

Katamtaman

This is when the adjective is accompanied by the words "medyo", "nang kauntî", "nang bahagyâ" or the repetition of the root word or the first two syllables of the root word.

Examples: medyo matabâ (somewhat fat), malakás nang bahagyâ (slightly strong), malakás-lakás (somewhat strong), matabáng nang kauntî (a little bit insipid)

Masidhî

This is when the adjective is accompanied by the words "napaka", "ubod ng", "saksakan ng", "talagáng", "sobrang", "masyadong" or the repetition of the whole adjective. The description in this degree is intense.

Examples: napakalakas (so strong), ubod ng baít (really kind), talagáng mabangó (truly fragrant), sobrang makinis (oversmooth)

Number

There are rules that are followed when forming adjectives that use the prefix "ma-".

Singular (Isahan)

When the adjective is describing only one noun/pronoun, "ma-" and the root word is used.

Examples: masayá (happy), malungkót (sad)

Plural (Maramihan)

When the adjective is describing two or more noun/pronoun, "ma-" is used and the first syllable or first two letters of the root word is repeated.

Examples: maliliít (small), magagandá (beautiful)

The word "mgá" is not needed if the noun/pronoun is right next to the adjective.

Example: Ang magagandáng damít ay kasya kiná Erica at Bel. (The beautiful clothes can fit to Erica and Bel.)

Ligature

The ligature (pang-angkóp) connects, or links, modifiers (like adjectives and adverbs) to the words that they are modifying. It has two allomorphs:

- na

This is used if the preceding word ends with a consonant other than n. It is not combined with the preceding word but separated, appearing between the modifier and the word it modifies.

Example: mapágmahál na tao ("loving person")

- -ng

This suffixed allomorph is used if the preceding word ends with a vowel or n; in the latter case, the final n is lost and replaced by the suffix:

Examples: mabuting nilaláng ng Diyos ("good creation of God"); huwarang mamámayán (huwaran + mamámayán) ("ideal citizen")

Conjunctions

Tagalog uses numerous conjunctions, and may belong to one of these possible functions:

- separate non-contrasting ideas (e.g. at "and")

- separate contrasting ideas (e.g. ngunit "but")

- give explanations (e.g. kung "if")

- provide circumstances (e.g. kapág "when")

- indicate similarities (e.g. kung saán "where")

- provide reasons (e.g. dahil "because")

- indicate endings (e.g. upang "[in order] to")

Modifiers

Summarize

Perspective

Modifiers alter, qualify, clarify, or limit other elements in a sentence structure. They are optional grammatical elements but they change the meaning of the element they are modifying in particular ways. Examples of modifiers are adjectives (modifies nouns), adjectival clauses, adverbs (modifies verbs), and adverbial clauses. Nouns can also modify other nouns. In Tagalog, word categories are fluid: A word can sometimes be an adverb or an adjective depending on the word it modifies. If the word being modified is a noun, then the modifier is an adjective, if the word being modified is a verb, then it is an adverb. For example, the word 'mabilís' means 'fast' in English. The Tagalog word 'mabilís' can be used to describe nouns like 'kuneho' ('rabbit') in 'kunehong mabilís' ('quick rabbit'). In that phrase, 'mabilís' was used as an adjective. The same word can be used to describe verbs, one can say 'tumakbóng mabilís' which means 'quickly ran'. In that phrase, 'mabilis' was used as an adverb. The Tagalog word for 'rabbit' is 'kuneho' and 'ran' is 'tumakbó' but they showed up in the phrases as 'kuneho-ng' and 'tumakbó-ng'. Tagalog uses something called a "linker" that always surfaces in the context of modification.[8] Modification only occurs when a linker is present. Tagalog has the linkers -ng and na. In the examples mentioned, the linker -ng was used because the word before the linker ends in a vowel. The second linker, na is used everywhere else (the na used in modification is not the same as the adverb na which means 'now' or 'already'). Seeing the enclitics -ng and na are good indications that there is modification in the clause. These linkers can appear before or after the modifier.

The following table[9] summarizes the distribution of the linker:

| Required | Prohibited |

|---|---|

| Attributive Adjective | Predicative Adjective |

| Adverbial modifier | Predicative Adverbial |

| Nominal Modifier | Predicative Nominal |

| Relative Clause | Matrix Clause |

Sequence of modifiers in a noun phrase

The following tables show a possible word order of a noun phrase containing a modifier.[10] Since word order is flexible in Tagalog, there are other possible ways in which one could say these phrases. To read more on Tagalog word order, head to the Word Order section.

| Marker | Possessive | Quantity | Verbal Phrase | Adjectives | Noun | Head Noun | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Example | ang | kaniyáng | apat na | piniritong | mahabang | Vigang | lumpiâ |

| Gloss | the | her | four | fried | long | Vigan | spring roll |

| Translation | her four fried, long Vigan spring rolls | ||||||

| Example | iyáng | inyóng | limáng kahóng | binasag ng batang | putíng | Intsík na | pinggán |

| Gloss | those | your | five boxes | that the children broke | white | Chinese | plates |

| Translation | those five boxes of yours of white Chinese plates that the children broke | ||||||

Enclitic particles

Summarize

Perspective

Tagalog has enclitic particles that have important information conveying different nuances in meaning. Below is a list of Tagalog's enclitic particles.

- na and pa

- na: now, already

- pa: still, else, in addition, yet

- man, kahit: even, even if, even though

- bagamán: although

- ngâ: indeed; used to affirm or to emphasise. Also softens imperatives.

- din (after a vowel: rin): too, also

- lamang (contracted as lang): limiting particle; only or just

- daw (after a vowel: raw): a reporting particle that indicates the preceding information as secondhand; they say, he said, reportedly, supposedly, etc.

- pô (less respectful form: hô): marker indicating politeness.

- ba: used to end yes-and-no questions and optionally in other types of questions, similar to Japanese -ka and Chinese ma (嗎), but not entirely.

- muna: for now, for a minute, and yet (when answering in the negative).

- namán: used in making contrasts; softens requests; emphasis

- kasí: expresses cause; because

- kayâ: expresses wonder; I wonder; perhaps (we should do something); also optionally used in yes-and-no questions and other forms of questions

- palá: expresses that the speaker has realized or suddenly remembered something; realization particle; apparently

- yatà (contracted as/informal: atà): expresses uncertainty; probably, perhaps, seems

- tulóy: used in cause and effect; as a result

- sana: expresses hope, unrealized condition (with the verb in completed aspect), used in conditional sentences.

The order listed above is the order in which the particles follow if they are used in conjunction with each other. A more concise list of the orders of monosyllabic particles from Rubino (2002) is given below.[11]

- na / pa

- ngâ

- din ~ rin

- daw ~ raw

- pô / hô

- ba

The particles na and pa cannot be used in conjunction with each other as well as pô and hô.

- Dumatíng na raw palá ang lola mo.

- "Oh yes, your grandmother has apparently arrived."

- Palitán mo na rin.

- "Do change it as well."

Note for "daw/raw and rin/din": If the preceding letter is a consonant except y and w, the letter d is used in any word, vice versa for r e.g., pagdárasal, instead of pagdádasal

Although in everyday speech, this rule is often ignored.

- Walâ pa yatang asawa ang kapatíd niyá.

- "Perhaps his brother still hasn’t a wife."

- Itó lang kayâ ang ibibigáy nilá sa amin?

- "I wonder, is the only thing that they'll be giving us?"

- Nag-aral ka na ba ng wikang Kastilà?

- "Have you already studied the Spanish language?"

- Batà pa kasí.

- "He's still young, is why."

- Pakisulat mo ngâ muna ang iyóng pangalan dito.

- "Please, do write your name here first."

The words daw and raw, which mean “he said”/“she said”/“they said”, are sometimes joined to the real translations of “he said”/”she said”, which is sabi niyá, and “they said”, which is sabi nilá. They are also joined to the Tagalog of “you said”, which is sabi mo. But this time, both daw and raw mean “supposedly/reportedly”.

- Sabi raw niyá. / Sabi daw niyá.

- "He/she supposedly said."

- Sabi raw nilá. / Sabi daw nilá.

- "They supposedly said."

- Sabi mo raw. / Sabi mo daw.

- "You supposedly said."

Although the word kasí is a native Tagalog word for “because” and not slang, it is still not used in formal writing. The Tagalog word for this is sapagká’t or sapagkát. Thus, the formal form of Batà pa kasí is Sapagká’t batà pa or Sapagkát batà pa. This is sometimes shortened to pagká’t or pagkát, so Sapagká’t batà pa is also written as Pagká’t batà pa or Pagkát batà pa. In both formal and everyday writing and speech, dahil sa (the oblique form of kasí; thus, its exact translation is “because of”) is also synonymous to sapagká’t (sapagkát), so the substitute of Sapagká’t batà pa for Batà pa kasí is Dahil sa batà pa. Most of the time in speech and writing (mostly every day and sometimes formal), dahil sa as the Tagalog of “because” is reduced to dahil, so Dahil sa batà pa is spoken simply as Dahil batà pa.

Word order

Summarize

Perspective

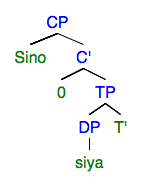

The accessibility of this section is in question. The specific issue is: Missing image descriptions and in-text equivalents for syntax trees. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. (November 2021) |

Tagalog has a flexible word order compared to English. While the verb always remains in the initial position, the order of noun phrase complements that follows is flexible. An example provided by Schacter and Otanes can be seen in (1).

(1)

Nagbigáy

gave

ng=libró

GEN=book

sa=babae

DAT=woman

ang=lalaki

NOM=man

(Kroeger, 1991: 136 (2))

The man gave the woman a book.

The flexibility of Tagalog word order can be seen in (2). There are six different ways of saying 'The man gave the woman a book.' in Tagalog. The following five sentences, along with the sentence from (1), include the same grammatical components and are all grammatical and identical in meaning but have different orders.

| (2)

(Kroeger, 1991: 136 (2)) |

Nagbigáy gave ng=libró GEN=book ang=lalaki NOM=man sa=babae DAT=woman Nagbigáy gave sa=babae DAT=woman ng=libró GEN=book ang=lalaki NOM=man Nagbigáy gave sa=babae DAT=woman ang=lalaki NOM=man ng=libró GEN=book Nagbigáy gave ang=lalaki NOM=man sa=babae DAT=woman ng=libró GEN=book Nagbigáy gave ang=lalaki NOM=man ng=libró GEN=book sa=babae DAT=woman |

The principles in (3) help to determine the ordering of possible noun phrase complements.[12] In a basic clause where the patient takes the nominative case, principles (i) and (ii) requires the actor to precede the patient. In example (4a), the patient, 'liham' (letter) takes the nominative case and satisfies principles (i) and (ii). The example in (4b) shows that the opposite ordering of the agent and patient does not result in an ungrammatical sentence but rather an unnatural one in Tagalog.

|

(4a) Sinulat PERF=write ni=Juan GEN=John ang=liham. NOM=letter (Kroeger, 1991: 137 (4))

John wrote the letter. (4b) ?Sinulat PERF=write ang=liham NOM=letter ni=Juan GEN=John (Kroeger, 1991: 137 (4))

John wrote the letter.

|

In example (5), the verb, 'binihag', (captivated) is marked for active voice and results in the actor ('Kuya Louis') to take the nominative case. Example (5) doesn't satisfy principles (i) and (ii). That is, principle (i) requires the Actor ('Kuya Louis') to precede all other arguments. However, since the Actor also takes the nominative case, principle (ii) requires the phrase 'Kuya Louis' to come last. The preferred order of agent and patient in Tagalog active clauses is still being debated. Therefore, we can assume that there are two "unmarked" word orders: VSO or VOS.

(5)

Binihag

PERF-capture-OV

si=Kuya Luis

NOM=big brother Luis

ng=kagandahan

GEN=beauty

ni=Emma

GEN=Emma

(Kroeger, 1991: 137 (5))

Big brother Luis was captivated by Emma's beauty.

A change in word order and trigger generally corresponds to a change in definiteness ("the" vs "a") in English. Example (6) shows a change in word order, triggered by the indirect, "ng." Example (7) shows a change in word order, triggered by the direct, "ang."

(6)

B(in)asa

P=read

ng

INDIR

tao

person

ang

DIR

libró.

book

A person read the book.

(7)

B(um)asa

A=read

ang

DIR

tao

person

ng

INDIR

libró

book

The person read a book.

Word order may be inverted (referred to in Tagalog grammar as Kabalikáng Anyô) by way of the inversion marker 'ay ' ( ’y after vowels in informal speech, not usually used in writing). Contrary to popular belief, this is not the copula 'to be' as 'ay' does not behave as an existential marker in an SVO structure and an inverted form VSO does not require 'ay' since the existentiality is denoted by case marking. A slight, but optional, pause in speech or a comma in writing may replace the inversion marker. This construction is often viewed by native speakers as formal or literary.

In this construction (ay-inversion), the 'ay' appears between the fronted constituent and the remainder of the clause. The fronted constituent in the construction includes locations and adverbs. Example (8)- (11) shows the inverted form of the sentences in the previous examples above.

(8)

Ang

DIR

batà

child

ay

ay

kumakantá

singing

The child is singing.

(9)

Ang

DIR

serbesa

beer

'y

ay

iniinom

drinking

nila

them

They are drinking the beer.

(10)

Ang

DIR

mga=dalaga

PL=girls

'y

ay

magagandá.

beautiful

The girls are beautiful.

(11)

Ang

DIR

ulán

rain

ay

ay

malakás

strong

The rain is strong.

In (8) and (11), the fronted constituent is the subject. On the other hand, in (9), the fronted constituent is the object. Another example of a fronted constituent in Tagalog is, wh-phrases. Wh-phrases include interrogative questions that begin with: who, what, where, when, why, and how. In Tagalog, wh-phrases occur to the left of the clause. For example, in the sentence, 'Who are you?', which translates to, 'Sino ka?' occurs to the left of the clause. The syntactic tree of this sentence is found in (12a). As we can see in (12a), the complementizer position is null. However, in the case where an overt complementizer is present, Sabbagh (2014) proposes that the wh-phrase lowers from Spec, CP, and adjoins to TP when C is overt (12b). The operation in (12b) is known as, WhP lowering.

|

|

This operation of lowering can also be applied in sentences to account for the verb-initial word order in Tagalog. The subject-lowering analysis states that "the subject lowers from Spec, TP and adjoins to a projection dominated by TP.".[13] If we use the example from (2), Nagbigáy ang lalaki ng libró sa babae. and applied subject lowering, we would see the syntax tree in (13a).If we lowered the subject, ang lalaki, to an intermediate position within VP, we would be able to achieve a VOS word order and still satisfy subject lowering.[13] This can be seen in (13b).

|

Lowering is motivated by a prosodic constraint called, WeakStart.[14] This constraint is largely based on the phonological hierarchy. This constraint requires the first phonological element within a phonological domain to be lower on the prosodic hierarchy than elements that follow it, within the same domain.[15]

Negation

There are three negation words: hindî, walâ, and huwág.

Hindî negates verbs and equations. It is sometimes contracted to ‘dî.

- Hindî akó magtatrabaho bukas.

- "I will not work tomorrow."

- Hindî mayaman ang babae.

- "The woman is not rich."

Walâ is the opposite of may and mayroón ("there is").

- Walâ akóng pera.

- Akó ay waláng pera.

- "I do not have money."

- Waláng libró sa loób ng bahay niyá.

- "There are no books in his house."

Huwág is used in expressing negative commands. It can be used for the infinitive and the future aspect. It is contracted as ‘wag.

- Huwág kang umiyák.

- "Do not cry."

- Huwág kayóng tumakbó rito.

- "Do not run here."

There are two (or more) special negative forms for common verbs:

- Gustó/Ibig/Nais ko nang kumain.

- "I would like to eat now." (Positive)

- Ayaw ko pang kumain.

- "I don't want to eat yet." (Negative)

Interrogative words

Summarize

Perspective

Tagalog's interrogative words are: alín, anó, bákit, gaáno, gaálin, makáilan, ilán, kailán, kaníno, kumustá, magkáno, nakaníno, nasaán, níno, paáno, pasaán, saán, tagasaán, and síno. With the exceptions of bakit, kamustá(maáno), and nasaán, all of the interrogative words have optional plural forms which are formed by reduplication. They are used when the person who is asking the question anticipates a plural answer and can be called wh-phrases. The syntactic position of these types of phrases can be seen in (12a).

(14a)

Alíng

Which

palda

skirt

ang

DEF

gustó

like

mo?

you

Which skirt do you like?

(14b)

Anó

What

ang

DEF

ginagawâ

doing

mo?

you?

What are you doing?

(14c)

Bakit

Why

nasa

in

Barcelona

Barcelona

sila?

they

Why are they in Barcelona?

(14d)

Kailán

When

uuwì

go home

si-=Victor

Victor

When will Victor go home?

(14e)

Nasaán

Where

si=Antonia?

Antonia

Where is Antonia?

Gaano (from ga- + anó) means how but is used in inquiring about the quality of an adjective or an adverb. The root word of the modifier is prefixed with ga- in this construction (16a).Ilán means how many (16b). Kumustá is used to inquire how something is (are).(16c) It is frequently used as a greeting meaning How are you? It is derived from the Spanish ¿cómo está?. Magkano (from mag- + gaano) means how much and is usually used in inquiring the price of something (16d). Paano (from pa- + anó) is used in asking how something is done or happened (16e).

(15a)

Gaano

How

ka

you

katagál

long

sa

in

Montreal?

Montreal?

How long will you be in Montreal?

(15b)

Iláng

How many

taón

year

ka

you

na?

now?

How old are you?

(15c)

Kumusta

How

ka?

you?

How are you?

(15d)

Magkano

How much

ang

DEF

kotseng

car

iyón?

that

How much is that car?

(15e)

Paano

How

mo

you

gagawin?

do

How will you do this?

(15f)

Gaalin

How long

galíng

from

dito

here

hanggang

to

doon?

there

How long does it take from here to there?

Nino (from ni + anó) means who, whose, and whom (18a). It is the indirect and genitive form of sino. Sino (from si + anó) means who and whom and it is in the direct form (18b). Kanino (from kay + anó) means whom or whose (18c). It is the oblique form of sino (who).

(18a)

Ginawâ

PAST=do

nino?

Who

Who did it?

(18b)

Sino

Who

siyá

she/he

Who is he/she?

(18c)

Kanino

Whose

itó

this

Whose is this?

See also

Notes

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.