Speaking in tongues

Phenomenon in which people speak words apparently in languages unknown to them From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Speaking in tongues, also known as glossolalia, is an activity or practice in which people utter words or speech-like sounds, often thought by believers to be languages unknown to the speaker. One definition used by linguists is the fluid vocalizing of speech-like syllables that lack any readily comprehensible meaning. In some cases, as part of religious practice, some believe it to be a divine language unknown to the speaker.[1] Glossolalia is practiced in Pentecostal and charismatic Christianity,[2][3] as well as in other religions.[4]

Sometimes a distinction is made between "glossolalia" and "xenolalia", or "xenoglossy", which specifically relates to the belief that the language being spoken is a natural language previously unknown to the speaker.[5][failed verification][6]

Etymology

Glossolalia is a borrowing of the γλωσσολαλία (glossolalía), which is a compound of the γλῶσσα (glossa) 'tongue, language'[7] and λαλέω (laleō) 'to speak, talk, chat, prattle, make a sound'.[8] The Greek expression (in various forms) appears in the New Testament in the books of Acts and First Corinthians. In Acts 2, the followers of Christ receive the Holy Spirit and speak in the languages of at least fifteen countries or ethnic groups.

The exact phrase speaking in tongues has been used at least since the translation of the New Testament into Middle English in the Wycliffe Bible in the 14th century.[9] Frederic Farrar first used the word glossolalia in 1879.[10]

Linguistics

Summarize

Perspective

In 1972, William J. Samarin, a linguist from the University of Toronto, published a thorough assessment of Pentecostal glossolalia[11] that became a classic work on its linguistic characteristics.[citation needed] His assessment was based on a large sample of glossolalia recorded in public and private Christian meetings in Italy, the Netherlands, Jamaica, Canada, and the United States over the course of five years; his wide range of subjects included the Puerto Ricans of the Bronx, the snake handlers of the Appalachians and the Molokans from Russia in Los Angeles.[12]

Samarin found that glossolalic speech does resemble human language in some respects. The speaker uses accent, rhythm, intonation and pauses to break up the speech into distinct units. Each unit is itself made up of syllables, the syllables being formed from consonants and vowels found in a language known to the speaker:

It is verbal behaviour that consists of using a certain number of consonants and vowels ... in a limited number of syllables that in turn are organized into larger units that are taken apart and rearranged pseudogrammatically ... with variations in pitch, volume, speed and intensity.[13]

[Glossolalia] consists of strings of syllables, made up of sounds taken from all those that the speaker knows, put together more or less haphazardly but emerging nevertheless as word-like and sentence-like units because of realistic, language-like rhythm and melody.[14]

That the sounds are taken from the set of sounds already known to the speaker is confirmed by others.[15] Felicitas Goodman, a psychological anthropologist and linguist, also found that the speech of glossolalists reflected the patterns of speech of the speaker's native language.[16] These findings were confirmed by Kavan (2004).[17]

Samarin found that the resemblance to human language was merely on the surface and so concluded that glossolalia is "only a facade of language".[18] He reached this conclusion because the syllable string did not form words, the stream of speech was not internally organized, and – most importantly of all – there was no systematic relationship between units of speech and concepts. Humans use language to communicate, but glossolalia does not. Therefore, he concluded that glossolalia is not "a specimen of human language because it is neither internally organized nor systematically related to the world man perceives".[18] On the basis of his linguistic analysis, Samarin defined Pentecostal glossolalia as "meaningless but phonologically structured human utterance, believed by the speaker to be a real language but bearing no systematic resemblance to any natural language, living or dead".[19]

Felicitas Goodman studied a number of Pentecostal communities in the United States, the Caribbean, and Mexico; these included English-, Spanish- and Mayan-speaking groups. She compared what she found with recordings of non-Christian rituals from Africa, Borneo, Indonesia and Japan. She took into account both the segmental structure (such as sounds, syllables, phrases) and the supra-segmental elements (rhythm, accent, intonation) and concluded that there was no distinction between what was practised by the Pentecostal Protestants and the followers of other religions.[20][page needed]

History

Summarize

Perspective

Classical antiquity

It was a commonplace idea within the Ancient world that divine beings spoke languages different from human languages, and historians of religion have identified references to esoteric speech in Greco-Roman literature that resemble glossolalia, sometimes explained as angelic or divine language.[21] An example is the account in the Testament of Job, a non-canonical elaboration of the Book of Job, where the daughters of Job are described as being given sashes enabling them to speak and sing in angelic languages.[22]

According to Dale B. Martin, glossolalia was accorded high status in the ancient world due to its association with the divine. Alexander of Abonoteichus may have exhibited glossolalia during his episodes of prophetic ecstasy.[23] Neoplatonist philosopher Iamblichus linked glossolalia to prophecy, writing that prophecy was divine spirit possession that "emits words which are not understood by those that utter them; for they pronounce them, as it is said, with an insane mouth (mainomenό stomati) and are wholly subservient, and entirely yield themselves to the energy of the predominating God".[24]

In his writings on early Christianity, the Greek philosopher Celsus includes an account of Christian glossolalia. Celsus describes prophecies made by several Christians in Palestine and Phoenicia of which he writes, "Having brandished these threats they then go on to add incomprehensible, incoherent, and utterly obscure utterances, the meaning of which no intelligent person could discover: for they are meaningless and nonsensical, and give a chance for any fool or sorcerer to take the words in whatever sense he likes".[23]

References to speaking in tongues by the Church fathers are rare. Except for Irenaeus' 2nd-century reference to many in the church speaking all kinds of languages "through the Spirit", and Tertullian's reference in 207 AD to the spiritual gift of interpretation of tongues being encountered in his day, there are no other known first-hand accounts of glossolalia, and very few second-hand accounts among their writings.[25]

1100 to 1900

- 12th century – Bernard of Clairvaux explained that speaking tongues was no longer present because there were greater miracles – the transformed lives of believers.[26]

- 12th century – Hildegard of Bingen is said to have possessed the gift of visions and prophecy and to have been able to speak and write in Latin without having learned the language.[27]

- 1265 – Thomas Aquinas wrote about the gift of tongues in the New Testament, which he understood to be an ability to speak every language, given for the purposes of missionary work. He explained that Christ did not have this gift because his mission was to the Jews, "nor does each one of the faithful now speak save in one tongue"; for "no one speaks in the tongues of all nations, because the Church herself already speaks the languages of all nations".[28]

- 15th century – The Moravians are referred to by detractors as having spoken in tongues. John Roche, a contemporary critic, claimed that the Moravians "commonly broke into some disconnected Jargon, which they often passed upon the vulgar, 'as the exuberant and resistless Evacuations of the Spirit'".[29]

- 17th century – The French Prophets: The Camisards also spoke sometimes in languages that were unknown: "Several persons of both Sexes", James Du Bois of Montpellier recalled, "I have heard in their Extasies pronounce certain words, which seem'd to the Standers-by, to be some Foreign Language". These utterances were sometimes accompanied by the gift of interpretation exercised, in Du Bois' experience, by the same person who had spoken in tongues.[30][31]

- 17th century – Early Quakers, such as Edward Burrough, make mention of tongues-speaking in their meetings: "We spoke with new tongues, as the Lord gave us utterance, and His Spirit led us".[32]

- 1817 – In Germany, Gustav von Below, an aristocratic officer of the Prussian Guard, and his brothers, founded a religious movement based on their estates in Pomerania, which may have included speaking in tongues.[33]

- 19th century – Edward Irving and the Catholic Apostolic Church. Edward Irving, a minister in the Church of Scotland, writes of a woman who would "speak at great length, and with superhuman strength, in an unknown tongue, to the great astonishment of all who heard, and to her own great edification and enjoyment in God".[34] Irving further stated that "tongues are a great instrument for personal edification, however mysterious it may seem to us".[35]

- 19th century – The history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), contains extensive references to the practice of speaking in tongues by Brigham Young, Joseph Smith and many others.[36][37] Sidney Rigdon had disagreements with Alexander Campbell regarding speaking in tongues, and later joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Speaking in tongues was recorded in contemporary sources, both hostile and sympathetic to Mormonism, by at least 1830.[38] The practice was soon widespread amongst Mormons, with many rank and file church members believing they were speaking the language of Adam; some of the hostility towards Mormons stemmed from those of other faiths regarding speaking in tongues unfavorably, especially when practiced by children.[38] At the 1836 dedication of the Kirtland Temple the dedicatory prayer asked that God grant them the gift of tongues and at the end of the service Brigham Young spoke in tongues, another elder interpreted it and then gave his own exhortation in tongues. Many other worship experiences in the Kirtland Temple prior to and after the dedication included references to people speaking and interpreting tongues. In describing the beliefs of the church in the Wentworth letter (1842), Joseph Smith identified a belief of the "gift of tongues" and "interpretation of tongues". The practice of glossolalia by the Latter-day Saints was widespread but after an initial burst of enthusiastic growth circa 1830–34, seems to have been somewhat more restrained than in many other contemporary religious movements.[38] Young, Smith, and numerous other early leaders frequently cautioned against the public exercise of glossolalia unless there be someone who could exercise the corresponding spiritual gift of interpretation of tongues, so that listeners could be edified by what had been said. Although the Latter-day Saints believe that speaking in tongues and the interpretation of tongues is alive and well in the Church, modern Mormons are much more likely to point to the way in which LDS missionaries are trained and learn foreign languages quickly, and are able to communicate rapidly on their missions, as evidence of the manifestation of this gift. This interpretation stems from a 1900 General Conference sermon by Joseph F. Smith which discouraged glossolalia; subsequent leaders echoed this recommendation for about a decade afterwards and subsequently the practice had largely died out amongst Mormons by the 1930s and '40s.[38]

20th century

During the 20th century, glossolalia primarily became associated with Pentecostalism and the later charismatic movement. Preachers in the Holiness Movement preachers Charles Parham and William Seymour are credited as co-founders of the movement. Parham and Seymour taught that "baptism of the Holy Spirit was not the blessing of sanctification but rather a third work of grace that was accompanied by the experience of tongues".[3] It was Parham who formulated the doctrine of "initial evidence". After studying the Bible, Parham came to the conclusion that speaking in tongues was the Bible evidence that one had received the baptism with the Holy Spirit.

In 1900, Parham opened Bethel Bible College in Topeka, Kansas, America, where he taught initial evidence, a Charismatic belief about how to initiate the practice. During a service on 1 January 1901, a student named Agnes Ozman asked for prayer and the laying on of hands to specifically ask God to fill her with the Holy Spirit. She became the first of many students to experience glossolalia, in the first hours of the 20th century. Parham followed within the next few days. Parham called his new movement the apostolic faith. In 1905, he moved to Houston and opened a Bible school there. One of his students was William Seymour, an African-American preacher. In 1906, Seymour traveled to Los Angeles where his preaching ignited the Azusa Street Revival. This revival is considered the birth of the global Pentecostal movement. According to the first issue of William Seymour's newsletter, The Apostolic Faith, from 1906:

A Mohammedan, a Soudanese by birth, a man who is an interpreter and speaks sixteen languages, came into the meetings at Azusa Street and the Lord gave him messages which none but himself could understand. He identified, interpreted and wrote a number of the languages.[39]

Parham and his early followers believed that speaking in tongues was xenoglossia, and some followers traveled to foreign countries and tried to use the gift to share the Gospel with non-English-speaking people. From the time of the Azusa Street revival and among early participants in the Pentecostal movement, there were many accounts of individuals hearing their own languages spoken 'in tongues'. The majority of Pentecostals and Charismatics consider speaking in tongues to primarily be divine, or the "language of angels", rather than human languages.[40] In the years following the Azusa Street revival Pentecostals who went to the mission field found that they were unable to speak in the language of the local inhabitants at will when they spoke in tongues in strange lands.[41]

The revival at Azusa Street lasted until around 1915. From it grew many new Pentecostal churches as people visited the services in Los Angeles and took their newfound beliefs to communities around the United States and abroad. During the 20th century, glossolalia became an important part of the identity of these religious groups. During the 1960s, the charismatic movement within the mainline Protestant churches and among charismatic Roman Catholics adopted some Pentecostal beliefs, and the practice of glossolalia spread to other Christian denominations. The discussion regarding tongues has permeated many branches of Protestantism, particularly since the widespread charismatic movement in the 1960s. Many books have been published either defending[42] or attacking[43] the practice.

Christianity

Summarize

Perspective

Theological explanations

In Christianity, a supernatural explanation for glossolalia is advocated by some and rejected by others. Proponents of each viewpoint use the biblical writings and historical arguments to support their positions.

- Glossolalists could, apart from those practicing glossolalia, also mean all those Christians who believe that the Pentecostal/charismatic glossolalia practiced today is the "speaking in tongues" described in the New Testament. They believe that it is a miraculous charism or spiritual gift. Glossolalists claim that these tongues can be both real, unlearned languages (i.e., xenoglossia)[44][45] as well as a "language of the spirit", a "heavenly language", or perhaps the language of angels.[46]

- Cessationists believe that all the miraculous gifts of the Holy Spirit ceased to occur early in Christian history, and therefore that the speaking in tongues as practiced by Charismatic Christians is the learned utterance of non-linguistic syllables. According to this belief, it is neither xenoglossia nor miraculous, but rather taught behavior, possibly self-induced. These believe that what the New Testament described as "speaking in tongues" was xenoglossia, a miraculous spiritual gift through which the speaker could communicate in natural languages not previously studied.

- A third position claims that glossolalia does exist, but it is a form of prelest, not the "speaking in tongues" described in the New Testament. It believes glossolalia is part of a mediumistic technique where practitioners are manifesting genuine spiritual power, but this power is not necessarily of the Holy Spirit.[47]

- A fourth position conceivably exists, which believes the practice of "glossolalia" to be a folk practice and different from the legitimate New Testament spiritual gift of speaking/interpreting real languages. It is therefore not out of a belief that "miracles have ceased" (i.e., cessationism) that causes this group to discredit the supernatural origins of particular modern expressions of "glossolalia", but it is rather out of a belief that glossolalists have misunderstood Scripture and wrongly attributed to the Holy Spirit something that may be explained naturalistically.[48]

Biblical practice

There are five places in the New Testament where speaking in tongues is referred to explicitly:

- Mark 16:17 (though this is a disputed text), which records the instructions of Christ to the apostles, including his description that "they will speak with new tongues" as a sign that would follow "them that believe" in him.

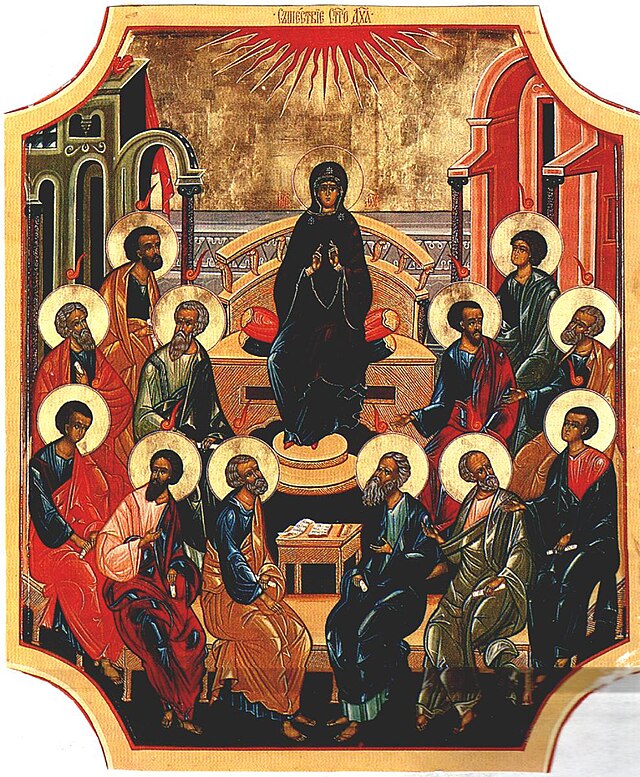

- Acts 2, which describes an occurrence of speaking in tongues in Jerusalem at Pentecost, though with various interpretations. Specifically, "every man heard them speak in his own language" and wondered "how hear we every man in our own tongue, wherein we were born?"

- Acts 10:46, when the household of Cornelius in Caesarea spoke in tongues, and those present compared it to the speaking in tongues that occurred at Pentecost.

- Acts 19:6, when a group of approximately a dozen men spoke in tongues in Ephesus as they received the Holy Spirit while the apostle Paul laid his hands upon them.

- 1 Cor 12, 13, 14, where Paul discusses speaking in "various kinds of tongues" as part of his wider discussion of the gifts of the Spirit; his remarks shed some light on his own speaking in tongues as well as how the gift of speaking in tongues was to be used in the church.

Other verses by inference may be considered to refer to "speaking in tongues", such as Isaiah 28:11, Romans 8:26 and Jude 20.

The biblical account of Pentecost in the second chapter of the book of Acts describes the sound of a mighty rushing wind and "divided tongues like fire" coming to rest on the apostles.[49] The text further describes that "they were all filled with the Holy Spirit, and began to speak in other languages". It goes on to say in verses 5–11 that when the Apostles spoke, each person in attendance "heard their own language being spoken". Therefore, the gift of speaking in tongues refers to the Apostles' speaking languages that the people listening heard as "them telling in our own tongues the mighty works of God". Glossolalists and cessationists both recognize this as xenoglossia, a miraculous ability that marked their baptism in the Holy Spirit. Something similar (although perhaps not xenoglossia) took place on at least two subsequent occasions, in Caesarea and Ephesus.

Glossolalists and cessationists generally agree that the primary purpose of the gift of speaking in tongues was to mark the Holy Spirit being poured out. At Pentecost the Apostle Peter declared that this gift, which was making some in the audience ridicule the disciples as drunks, be the fulfilment of the prophecy of Joel, which described that God would pour out his Spirit on all flesh (Acts 2:17).[45]

Despite these commonalities, there are significant variations in interpretation.

- Universal. The traditional Pentecostal view is that every Christian should expect to be baptized in the Holy Spirit, the distinctive mark of which is glossolalia.[50] While most Protestants agree that baptism in the Holy Spirit is integral to being a Christian, others[51] believe that it is not separable from conversion and no longer marked by glossolalia. Pentecostals appeal to the declaration of the Apostle Peter at Pentecost, that "the gift of the Holy Spirit" was "for you and for your children and for all who are far off" (Acts 2:38–39). Cessationists reply that the gift of speaking in tongues was never for all (1 Cor 12:30). In response to those who say that the baptism in the Holy Spirit be not a separate experience from conversion, Pentecostals appeal to the question asked by the Apostle Paul to the Ephesian believers "Have ye received the Holy Ghost since ye believed?" (Acts 19:2).

- One gift. Different aspects of speaking in tongues appear in Acts and 1 Corinthians, such that the Assemblies of God declare that the gift in Acts "is the same in essence as the gift of tongues" in 1 Corinthians "but different in purpose and use".[50] They distinguish between (private) speech in tongues when receiving the gift of the Spirit, and (public) speech in tongues for the benefit of the church. Others assert that the gift in Acts was "not a different phenomenon" but the same gift being displayed under varying circumstances.[52] The same description – "speaking in tongues" – is used in both Acts and 1 Corinthians, and in both cases the speech is in an unlearned language.

- Direction. The New Testament describes tongues largely as speech addressed to God, but also as something that can potentially be interpreted into human language, thereby "edifying the hearers" (1 Cor 14:5, 13). At Pentecost and Caesarea the speakers were praising God (Acts 2:11; 10:46). Paul referred to praying, singing praise, and giving thanks in tongues (1 Cor 14:14–17), as well as to the interpretation of tongues (1 Cor 14:5), and instructed those speaking in tongues to pray for the ability to interpret their tongues so that others could understand them (1 Cor 14:13). While some people limit speaking in tongues to speech addressed to God – "prayer or praise",[44] others claim that speaking in tongues be the revelation from God to the church, and when interpreted into human language by those embued with the gift of interpretation of tongues for the benefit of others present, may be considered equivalent to prophecy.[53]

- Music. Musical interludes of glossolalia are sometimes described as singing in the Spirit. Some hold that singing in the Spirit is identified with singing in tongues in 1 Corinthians 14:13–19,[54][55] which they hold to be "spiritual or spirited singing", as opposed to "communicative or impactive singing" which Paul refers to as "singing with the understanding".[56]

- Sign for unbelievers (1 Cor 14:22). Some assume that tongues are "a sign for unbelievers that they might believe",[57] and so advocate it as a means of evangelism. Others point out that Paul quotes Isaiah to show that "when God speaks to people in language they cannot understand, it is quite evidently a sign of God's judgment"; so if unbelievers are baffled by a church service they cannot understand because tongues are spoken without being interpreted, that is a "sign of God's attitude", "a sign of judgment".[58] Some identify the tongues in Acts 2 as the primary example of tongues as signs for unbelievers.

- Comprehension. Some say that speaking in tongues was "not understood by the speaker".[44] Others assert that "the tongues-speaker normally understood his own foreign-language message".[59] This last comment seems to have been made by someone confusing the "gift of tongues" with the "gift of the interpretation of tongues" , which is specified as a different gift in the New Testament, but one that can be given to a person who also has the gift of tongues. In that case, a person understands a message in tongues that he has previously spoken in an unknown language.

Pentecostal and charismatic practices

Baptism with the Holy Spirit is regarded by the Holiness Pentecostals as being the third work of grace, following the new birth (first work of grace) and entire sanctification (second work of grace).[60][3] Holiness Pentecostals teach that this third work of grace is accompanied with glossolalia.[60][3]

Because Pentecostal and charismatic beliefs are not monolithic, there is not complete theological agreement on speaking in tongues.[citation needed] Generally, followers believe that speaking in tongues is a spiritual gift that can be manifested as either a human language or a heavenly supernatural language in three ways:[61]

- The "sign of tongues" refers to xenoglossia, wherein followers believe someone is speaking a language they have never learned.

- The "gift of tongues" refers to a glossolalic utterance spoken by an individual and addressed to a congregation of, typically, other believers.

- "Praying in the spirit" is typically used to refer to glossolalia as part of personal prayer.[62]

Many Pentecostals and charismatics quote Paul's words in 1 Corinthians 14 which established guidelines on the public use of glossolalia in the church at Corinth although the exegesis of this passage and the extent to which these instructions are followed is a matter of academic debate.[63]

The gift of tongues is often referred to as a "message in tongues".[64] Practitioners believe that this use of glossolalia requires an interpretation so that the gathered congregation can understand the message, which is accomplished by the interpretation of tongues.[citation needed] There are two schools of thought concerning the nature of a message in tongues:

- One school of thought believes it is always directed to God as prayer, praise, or thanksgiving but is spoken in for the hearing and edification of the congregation.[citation needed]

- The other school of thought believes that a message in tongues can be a prophetic utterance inspired by the Holy Spirit.[65] In this case, the speaker delivers a message to the congregation on behalf of God.[citation needed]

In addition to praying in the Spirit, many Pentecostal and charismatic churches practice what is known as singing in the Spirit.[66][67][68]

Interpretation of tongues

In Christian theology, the interpretation of tongues is one of the spiritual gifts listed in 1 Corinthians 12. This gift is used in conjunction with that of the gift of tongues – the supernatural ability to speak in a language (tongue) unknown to the speaker. The gift of interpretation is the supernatural enablement to express in an intelligible language an utterance spoken in an unknown tongue. This is not learned but imparted by the Holy Spirit; therefore, it should not be confused with the acquired skill of language interpretation. While cessationist Christians believe that this miraculous charism has ceased, Charismatic and Pentecostal Christians believe that this gift continues to operate within the church.[69] Much of what is known about this gift was recorded by St. Paul in 1 Corinthians 14. In this passage, guidelines for the proper use of the gift of tongues were given. In order for the gift of tongues to be beneficial to the edification of the church, such supernatural utterances were to be interpreted into the language of the gathered Christians. If no one among the gathered Christians possessed the gift of interpretation, then the gift of tongues was not to be publicly exercised. Those possessing the gift of tongues were encouraged to pray for the ability to interpret.[69]

Non-Christian practice

Other religious groups have been observed to practice some form of theopneustic glossolalia. It is perhaps most commonly in Paganism, Shamanism, and other mediumistic religious practices.[47] In Japan, the God Light Association believed that glossolalia could cause adherents to recall past lives.[4]

Glossolalia has been postulated as an explanation for the Voynich manuscript.[70]

In the 19th century, Spiritism was developed by the work of Allan Kardec, and the practice was seen as one of the self-evident manifestations of spirits. Spiritists argued that some cases were actually cases of xenoglossia.

Medical research

Summarize

Perspective

In most cases tongues speakers have no underlying neuropsychiatric disorder precipitating the manifestations, although it rarely occurs in neurogenic conditions.[71] Speakers report finding personal meaning in the utterances, although they are unintelligible and have no linguistic structure. The link to psychopathology has been disproven - tongues speakers are not over-represented in those with depression or psychosis, nor other disorders and one study found tongues speaking negatively associated with neuroticism - emotional stability was greater amongst the speakers.[72]: 69 Nevertheless the language spoken by the speakers is devoid of semantic meaning, although the utterances appear to be derived from the language of the speaker.[73]: 505 Studies have thus suggested this could be learned behaviour by the speakers.[74]

Neuroimaging of brain activity during glossolalia does not show activity in the language areas of the brain.[72][75] In other words, it may be characterized by a specific brain activity.[76][77]

A 1973 experimental study highlighted the existence of two basic types of glossolalia: a static form which tends to a somewhat coaction to repetitiveness and a more dynamic one which tends to free association of speech-like elements.[78][76]

A study done by the American Journal of Human Biology found that speaking in tongues is associated with both a reduction in circulatory cortisol, and enhancements in alpha-amylase enzyme activity – two common biomarkers of stress reduction that can be measured in saliva.[79] Several sociological studies report various social benefits of engaging in Pentecostal glossolalia,[80][81] such as an increase in self-confidence.[81]

As of April 2021, further studies are needed to corroborate the 1980s view of glossolaly with more sensitive measures of outcome, by using the more recent techniques of neuroimaging.[76] [better source needed]

Cessationism

Various Christian groups have criticized the Pentecostal and charismatic movement for paying too much attention to mystical manifestations, such as glossolalia.[82] In certain evangelical and other Protestant Churches, this experience was understood as a gift to speak foreign languages without having learned them (xenoglossy) for evangelization, and cessationism is the theological position that argues that this and other spiritual gifts were meant only for the apostolic age, and thereafter withdrawn.[83][84]

See also

- Aphasia – Inability to comprehend or formulate language

- Asemic writing – Wordless open semantic form of writing

- Automatic writing – Claimed psychic ability

- Biblical hermeneutics

- Covenant theology – Protestant biblical interpretive framework

- Direct revelation – Communication from God to a person

- Dispensationalism – Biblical interpretation

- Dream speech – Words in the mind during sleep

- Gibberish – Nonsensical speech or writing

- Historical-grammatical method – Christian hermeneutical method

- Idioglossia – Idiosyncratic language

- Logorrhoea – Communication disorder that causes excessive wordiness and repetitiveness

- Scat singing – Vocal improvisation with wordless vocables, nonsense syllables or without words at all

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.