Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

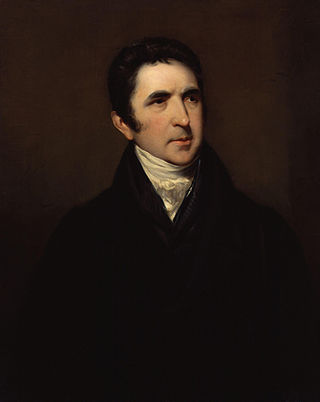

Sir John Barrow, 1st Baronet

English geographer, linguist, and civil servant (1764–1848) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Sir John Barrow, 1st Baronet, FRS, FRGS, FSA (19 June 1764 – 23 November 1848) was an English geographer, linguist, writer and civil servant best known for serving as the Second Secretary to the Admiralty from 1804 until 1845.

Remove ads

Remove ads

Early life

Barrow was born the only child of Roger Barrow, a tanner in the village of Dragley Beck, in the parish of Ulverston, Lancashire.[1] He was a pupil at Town Bank Grammar School, Ulverston, but left at the age of 13 to found a Sunday school for poor local children.

Barrow was employed as superintending clerk of an iron foundry at Liverpool. At only 16, he went on a whaling expedition to Greenland. By his twenties, he was teaching mathematics, in which he had always excelled, at a private school in Greenwich.[2][3]

Remove ads

China

Barrow taught mathematics to the son of Sir George Leonard Staunton; through Staunton's interest, he was attached on the first British embassy to China from 1792 to 1794 as comptroller of the household to Lord Macartney. He soon acquired a good knowledge of the Chinese language, on which he subsequently contributed articles to the Quarterly Review; and the account of the embassy published by Sir George Staunton records many of Barrow's valuable contributions to literature and science connected with China.[2]

Barrow ceased to be officially connected with Chinese affairs after the return of the embassy in 1794, but he always took much interest in them, and on critical occasions was frequently consulted by the British government.[2]

Some historians attribute the 'stagnation thesis' to Barrow; that China was an extremely civilized nation that was in a process of decay by the time of European contact.[4]

Remove ads

South Africa

Summarize

Perspective

The Castle at Cape Town in about 1800, painted by John Barrow

In 1797, Barrow accompanied Lord Macartney as private secretary in his mission to settle the government of the newly acquired colony of the Cape of Good Hope. Barrow was entrusted with the task of reconciling the Boer settlers and the native Black population and of reporting on the country in the interior. In the course of the trip, he visited all parts of the colony; when he returned, he was appointed auditor-general of public accounts. He then decided to settle in South Africa, married, and bought a house in 1800 in Cape Town. However, the surrender of the colony at the peace of Amiens (1802) upset this plan.

During his travels through South Africa, Barrow compiled copious notes and sketches of the countryside that he was traversing. The outcome of his journeys was a map which, despite its numerous errors, was the first published modern map of the southern parts of the Cape Colony.[5] Barrow's descriptions of South Africa greatly influenced Europeans' understanding of South Africa and its peoples.[4] William John Burchell (1781–1863) was particularly scathing: "As to the miserable thing called a map, which has been prefixed to Mr. Barrow’s quarto, I perfectly agree with Professor Lichtenstein, that it is so defective that it can seldom be found of any use."[citation needed]

Career in the Admiralty

Summarize

Perspective

Barrow returned to Britain in 1804 and was appointed Second Secretary to the Admiralty by Viscount Melville, a post which he held for forty years[2] – apart from a short period in 1806–1807 when there was a Whig government in power.[6] Lord Grey took office as Prime Minister in 1830, and Barrow was especially requested to remain in his post, starting the principle that senior civil servants stay in office on change of government and serve in a non-partisan manner. Indeed, it was during his occupancy of the post that it was renamed Permanent Secretary.[3] Barrow enjoyed the esteem and confidence of all the eleven chief lords who successively presided at the Admiralty board during that period, and more especially of King William IV while lord high admiral, who honoured him with tokens of his personal regard.[2]

In his position at the Admiralty, Barrow was a great promoter of Arctic voyages of discovery, including those of John Ross, William Edward Parry, James Clark Ross and John Franklin. Barrow Strait, Cape Barrow, and Cape John Barrow in the Canadian Arctic, as well as Point Barrow and the former city of Barrow in Alaska are named after him. He is reputed to have been the initial proposer of Saint Helena as the new place of exile for Napoleon Bonaparte following the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.[7][3] He is also remembered for infamously declaring the newly invented electrical telegraph as being "wholly unnecessary" and greatly delaying its proposed adoption by the admiralty.[8]

Barrow was a fellow of the Royal Society and received the degree of LL.D from the University of Edinburgh in 1821. A baronetcy was conferred on him by Sir Robert Peel in 1835.[9] He was also a member of the Raleigh Club, a forerunner of the Royal Geographical Society.[2] Barrow was subsequently one of the seven founding members of the Royal Geographical Society on 16 July 1830.[10]

Remove ads

Retirement and legacy

Barrow retired from public life in 1845 and devoted himself to writing a history of the modern Arctic voyages of discovery (1846), as well as his autobiography, published in 1847.[2] He died suddenly on 23 November 1848.[2] The Sir John Barrow monument was built in his honour on Hoad Hill overlooking his home town of Ulverston in 1850, though locally it is more commonly called Hoad Monument.[11] Mount Barrow and Barrow Island in Australia are believed to have been named after him.[12] Barrow's Goldeneye a species of duck from North America and Iceland is also named after him.

Barrow's legacy has been met with a mixed analysis. Some historians regard Barrow as an instrument of imperialism who portrayed Africa as a resource rich land devoid of any human or civilized elements.[13] Other historians consider Barrow to have promoted humanitarianism and rights for South Africans.[4] His renewal of Arctic voyages in search of the Northwest Passage and the Open Polar Sea has also been criticized, with author Fergus Fleming remarking that "perhaps no other man in the history of exploration has expended so much money and so many lives in so desperately pointless a dream".[14]

Remove ads

Private life

Barrow married Anna Maria Truter (1777–1857), a botanical artist from the Cape, in South Africa on 26 August 1799.[15] The couple had four sons and two daughters, one of whom, Johanna, married the artist Robert Batty.[16] His son George succeeded to his title. His second son, John Barrow (28 June 1808 – 9 December 1898), was appointed head of the Admiralty Records Office as a reward for developing a system for recording naval correspondence, and for rescuing documents dating back to the Elizabethan period. He published ten volumes of his travels, wrote biographies of Francis Drake and others and edited the voyages of Captain Cook[17] among other works.[18]

Remove ads

In fiction

Barrow in his role as Second Secretary is portrayed as a character in Hornblower and the Crisis by C. S. Forester.[19]

Bibliography

Summarize

Perspective

Besides 95 articles in the Quarterly Review,[3] Barrow published among other works:[2]

- Barrow, John (1792). A Description of Pocket and Magazine Cases of Mathematical Drawing Instruments, in which is explained the Use of each Instrument, and particularly, of the Sector and plain Scale, in the Solutions of a variety of Problems; likewise the Description, Construction, and Use of Gunter's Scale. London: J & W Watkins.

- — (1804). Travels in China, Containing Descriptions, Observations, And Comparison, Made And Collected in the Course of a Short Residence at the Imperial Palace of Yuen-Min-Yuen. London: T. Cadell And W. Davies. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- — (1806). A Voyage to Cochinchina in the Years 1792 and 1793. London: T. Cadell And W. Davies. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- — (1806). Travels into The Interior of Southern Africa. London: T. Cadell And W. Davies. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- — (1807). Some Account of the Public Life, And A Selection From The Unpublished Writings, of The Earl of McCartney. London: T. Cadell And W. Davies. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- — (1818). A Chronological History of Voyages into The Arctic Regions. London: John Murray. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- The Eventful History of the Mutiny and Piratical Seizure of H.M.S. Bounty: (1831) Its Cause and Consequences. John Murray. 1831.

- — (1843). The life, voyages, and exploits of Admiral Sir Francis Drake : with numerous original letters from him and the Lord High Admiral to the Queen and great officers of state. London: John Murray.

- — (1838). The Life of Richard Earl Howe, K.G., Admiral of the Fleet, And General of Marines. London: John Murray. Retrieved 15 August 2009.[20]

- An Auto-Biographical Memoir of Sir John Barrow, Bart, Late of the Admiralty. Including Reflections, Observations, and Reminiscences at Home and Abroad, from Early Life to Advanced Age; Murray, 1847 (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 978-1-108-00470-1)

- — (1839). The Life of George Lord Anson, Admiral of The Fleet; Vice-Admiral of Great Britain; And First Lord Commissioner of the Admiralty, Previous To, And During, The Seven-Years' War. London: John Murray. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- — (1840). The Life of Peter The Great (1908 ed.). London: John Murray. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- — (1845). A Description of Pitcairn's Island And Its Inhabitants (Harper's Stereotype Edition, 1845). New York: Harper & Brothers. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- — (1846). Voyages of Discovery And Research Within The Arctic Regions, From The Year 1818 to the Present Time. London: John Murray. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- Life & Correspondence of Admiral Sir William Sidney Smith G.C.B. – London: Richard Bentley, 1848 (See William Sidney Smith.)

- — (1848). Sketches of the Royal Society And Royal Society Club. London: John Murray. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- Staunton, George Thomas; John Barrow (1856). Memoirs of the Chief Incidents of the Public Life of Sir George Thomas Staunton, Bart. London: L. Booth. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

He was also the author of several valuable contributions to the seventh edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica.

Other reading

- Crusades against Frost:Frankenstein, Polar Ice, and Climate Change in 1818 – Siobhan Carroll.[21]

- Barrow's Boys – Fergus Fleming (1998)[22]

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads