Siege of Smerwick

Siege and massacre during the Second Desmond Rebellion, 1580 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The siege of Smerwick took place at Ard na Caithne (the Hill of the Arbutus Tree, known in English as Smerwick) in November 1580, during the Second Desmond Rebellion in Ireland. A force of between 400 and 700 Papal freelance soldiers, mostly of Spanish and Italian origin, landed at Smerwick to support the Catholic rebels. They were forced to retreat to the nearby promontory fort of Dún an Óir,[1] where they were besieged by the English. The Papal commander parleyed and was bribed, and the defenders surrendered within a few days. The officers were spared, but the other ranks were then summarily executed on the orders of the English commander, Arthur Grey (Baron Grey de Wilton), the Lord Deputy of Ireland.[2][3]

| Siege of Smerwick | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Desmond Rebellion | |||||||

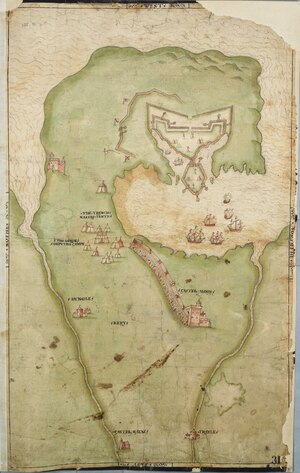

Map of the English attack on Spanish and Italian forces at Smerwick | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Kingdom of England | Papal and Spanish troops | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| The 14th Baron Grey de Wilton | Sebastiano di San Giuseppe | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~4,000 | 400–700 | ||||||

Background

Summarize

Perspective

James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald landed a small Papal invasion force in July 1579, initiating the Second Desmond rebellion. This continued for three years, though Fitzmaurice was killed within weeks of the landing.

The following year, on 10 September 1580, a squadron of Spanish ships under the command of Don Juan Martinez de Recalde landed a Papal force of Spanish and Italians at Smerwick, on the Dingle Peninsula, near Fitzmaurice's landing-point. The force numbered 600 men, and brought with it arms for several thousand. It was commanded by Sebastiano di San Giuseppe (a.k.a. Sebastiano da Modena), paid for and sent by Pope Gregory XIII, and was a clandestine initiative by Philip II of Spain to aid the rebellion. It was found later that none of the Spanish officers had a commission from King Philip, nor the Italians from Pope Gregory, though the latter had been granted indulgences for taking part. At the time, neither Spain nor the Papacy was formally at war with England, but the papal bull Regnans in Excelsis of 1570 had released observant Catholics from their allegiance to Queen Elizabeth I of England and Ireland.

Regarding the Papal force, the Irish historian Father CP Meehan commented: ".. in or about one thousand, ... most of them were brigands pardoned at the entreaty of Fitzmaurice on the strict understanding that they should clear out of the Pontifical States and take service under him in Ireland. Some of them, however, did not follow the free-booting profession, and we may assume that Ercole di Pisa was an honourable man, although a soldier of fortune. Be that as it may, his Holiness and travellers in Italy must have been glad to get rid of them all."[4]

Leading a rebel force of 4,000 men somewhere to the east, Gerald FitzGerald (Earl of Desmond), James Eustace (Viscount Baltinglass), and John of Desmond tried to link up to receive the supplies brought by the expeditionary force. English forces under Thomas Butler (Earl of Ormond) and Arthur Grey (Baron Grey de Wilton) (including Walter Raleigh and the poet Edmund Spenser as chronicler) blocked them, and Richard Bingham's ships blockaded their ships in the bay at Smerwick. San Giuseppe had no choice but to retreat to the fort at Dún an Óir, which however is a banked field with no spring or drinking water.

From information obtained from prisoners, Lord Ormond ascertained the size of the defending forces to be around 700, but with military equipment that would serve a force of 5,000; the prisoners said the defences of the fort were being strengthened. Ormond retreated, leaving a small party to keep Dún an Óir under surveillance.[5]

Siege

Summarize

Perspective

On 5 November, an English naval force led by Admiral Sir William Winter arrived at Smerwick Bay, replenishing the supplies of Grey de Wilton, who was camped at Dingle, and landing eight artillery pieces.[5] On 7 November, Grey de Wilton laid siege to the Smerwick garrison. The besieged forces were geographically isolated on the tip of the Dingle Peninsula, cut off by Mount Brandon, one of the highest mountains in Ireland, on one side, and the much larger English force on the other. The English forces began the artillery barrage on Dún an Óir on the morning of 8 November, which rapidly broke down the improvised defences of the fort.[5]

After a three-day siege, the commander Di San Giuseppe surrendered on 10 November.

Massacre

Accounts vary on whether they had been granted quarter. Grey de Wilton ordered the summary executions, sparing only the commanders. Grey had also heard that the main Irish rebel army of 4,000 "who had promised to be on the mountains", were somewhere in the hills to his east, looking to be rearmed and supplied by Di San Giuseppe, and they might, in turn, surround his army; but this army never appeared.

In Grey de Wilton's account, contained in a despatch to Queen Elizabeth I of England dated 11 November 1580, he rejected an approach made by the besieged Spanish and Italian forces to agree to terms of a conditional surrender in which they would cede the fort and leave. Grey de Wilton claimed that he insisted that they surrender without preconditions and put themselves at his mercy and that he subsequently rejected a request for a ceasefire. An agreement was finally made for an unconditional surrender the next morning, with hostages being taken by English forces to ensure compliance.[6] The following morning, an English force entered the fort to secure and guard armaments and supplies. Grey de Wilton's account in his despatch says "Then put I in certain bands, who straight fell to execution. There were six hundred slain." Grey de Wilton's forces spared those of higher rank: "Those that I gave life unto, I have bestowed upon the captains and gentlemen that hath well deserved ...."[6]

Sir Geoffrey Fenton wrote to London on 14 November about the prisoners that a further "20 or 30 Captains and Alphiaries [were] spared to report in Spain and Italy the poverty and infidelity of their Irish consociates."[7]

Margaret Anna Cusack (writing as M. F. Cusack) noted in 1871 that there had long been a degree of controversy about Grey de Wilton's version of events to Elizabeth, and identifies three other contemporary accounts which contradict it, by O'Daly, O'Sullivan Beare, and Russell. According to these versions, Grey de Wilton promised the garrison their lives in return for their surrender, a promise which he broke, remembered in the term "Grey's faith". Like Grey himself, none of these commentators can be described as neutral, as they were all either serving the state or opposed to it. Cusack's own interpretation of the events likewise could not be described as unbiased, given her position as a Catholic nun and fervent Irish nationalist at the time.[8]

Cusack confirmed that Di San Giuseppe (whom she named by the Spanish version, San José) had sold the "Fort del Ore" ('Fort of Gold', i.e. Dún an Óir) for a bribe: "Colonel Sebastian San José, who proved eventually so fearful a traitor to the cause he had volunteered to defend. [...] The Geraldine cause was reduced to the lowest ebb by the treachery of José."[9] She explained that:

In a few days the courage of the Spanish commander failed, and he entered into treaty with the Lord Deputy. A bargain was made that he should receive a large share of the spoils. He had obtained a personal interview in the Viceroy's camp, and the only persons for whom he made conditions were the Spaniards who had accompanied him on the expedition. The English were admitted to the fortress on the following day, and a feast was prepared for them.[9]

Cusack also mentions that some of the few who were spared summary execution actually suffered a worse fate: They were offered life if they would renounce their Catholic faith. Upon refusal, their arms and legs were broken in three places by an ironsmith. They were left in agony for a day and night and then hanged.[8] In contrast, Grey's report mentioned: "Execution of the Englishman who served Dr Sanders, and two others, whose arms and legs were broken for torture." He did not specify why they were tortured, nor refer to their religion.[10]

John Hooker states in his Supply to the Irish Chronicle (an addition to Holinshed's Chronicles) written in 1587, the bands ordered to carry out the executions were led by Captain Raleigh (later Sir Walter Raleigh) and Captain Mackworth.[11][12]

Richard Bingham, future commander of Connacht, was present and described events in a letter to Robert Dudley (Earl of Leicester), although he claimed the massacre was perpetrated by sailors.[13] The poet Edmund Spenser, then secretary to the Lord Deputy of Ireland, is also thought to have been present.[6]

According to the folklore of the area, the execution of the captives took two days, with many of the captives being beheaded in a field known locally in Irish as Gort a Ghearradh ('Field of Cutting'); their bodies later being thrown into the sea. Archaeologists have not yet discovered human remains at the site, although a nearby field is known as Gort na gCeann ('Field of the Heads') and local folklore recalls the massacre.[14]

In Raleigh's trial

Three decades after the siege, when Raleigh had fallen from favour, his involvement with this massacre was brought against him as a criminal charge in one of his trials. Raleigh argued that he was "obliged to obey the commands of his superior officer" but he was unable to exonerate himself.[2] He was executed on 29 October 1618, chiefly for his involvement in the Main Plot.

Monument

A monument to commemorate the victims of the massacre was erected at Smerwick in 1980.[15] The sculpture is by Irish sculptor Cliodhna Cussen.

See also

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.