Sack of Rome (390 BC)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The First sack of Rome[b] was the consequence of the victory of the Senone Gauls led by Brennus over the Roman troops during the Battle of the Allia, a military success allowing them to invest the city and demand the payment of a heavy ransom from the defeated Romans, but they were soon driven out from the city. The Sack of Rome has multiple accounts, including Polybius (II, 18, 2), Livy (V, 35–55), Diodorus Siculus (XIV, 113–117), Plutarch (Camillus, 15–32) and Strabo (V, 2–3). The accounts of the Battle of the Allia and the Sack of Rome were written centuries after the events, and their reliability is disputed by modern historians, who have shown that parts of the narrative are based on mythology, and others on transfers from Greek history.[10] Another uncertain information is the date of the start of the Siege: the historian Tacitus suggests July 18 of 390 BC (according to the Varronian calendar),[11] while modern sources suggest July 21 of 387 BC (according to the Polybian/Greek calendar), lasting as much as seven months.[12]

| First Sack of Rome | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Roman–Gallic Wars | |||||||

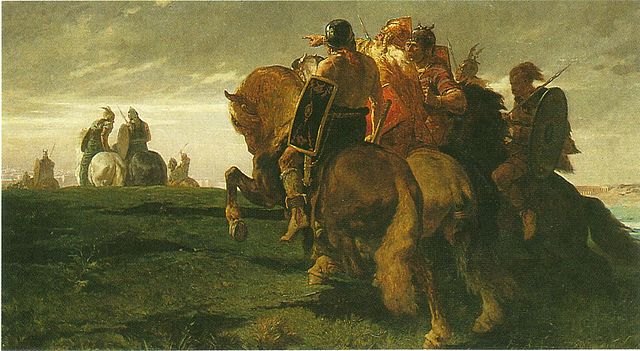

"Le Brenn et sa part de butin", Paul Jamin, 1893. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Senones | Roman Republic | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Chief Brennus †[8] |

Marcus Furius Camillus Manlius Capitolinus Quintus Sulpicius Longus | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 30,000+ men[9] | 24,000 men[citation needed] | ||||||

The Gauls in Rome

Summarize

Perspective

The departure to Caere

According to Livy , after the disaster of the Allia ("dies Alliensis"), realizing that the situation had become desperate, the Romans abandoned any idea of defending Rome. One of the first measures taken by the Roman authorities was to secure the sacred objects of the city, under the guard of the Vestal Virgins and the Flamenes.[12] They were sent to Caere (modern Cerveteri),[13] an allied Etruscan city, under the command of the plebeian Lucius Albinius[14][15] accompanied by part of the Roman population.[16]

The devotion of the elderly magistrates

For those remaining in Rome, it was decided that all men of fighting age ("militaris iuuentus") as well as senators in the prime of life, accompanied by their wives and children, should take refuge on the Arx (literally "hill of the citadel", since in Latin Arx means "citadel", "fortress") and on the Capitoline Hills, fortified positions that were easier to defend. The oldest magistrates ("seniores") pronounced the formula of devotio, by which they agreed to sacrifice themselves and await the arrival of the Gauls,[17] devoting themselves and their enemies to the infernal gods.[14][18]

The Gauls entered Rome three days after the Roman defeat on the Allia.[19] Not being equipped with siege engines,[18] the Gauls laid siege to the Capitoline Hills and quickly began to pillage the rest of the city. According to Livy, the signal for the pillage was given by an altercation between a certain Marcus Papirius and a Gallic warrior.[20] To defend himself from the warrior who was pulling his beard, the Roman struck him on the head with his ivory scepter, which triggered the massacre. The Gauls burned Rome and killed the inhabitants who remained there.

"After the murder of the high-ranking figures, no one was spared, houses were looted and burned."

The Siege of the Capitoline Citadel

Marcus Furius Camillus, who had escaped the disaster of the Allia, kept informed of events from Ardea, where he was in exile, began to assemble a relief army, with the survivors of the Allia who had taken refuge in Veii.[21] Despite their recent defeat, the latter had launched attacks against Etruscan raiders who had come to prowl around Rome to take advantage of the situation.[15]

Meanwhile, in Rome, the Gallic besiegers attempted an assault on the Roman citadel, but the attack was repelled.[22] Plutarch does not clearly mention this assault. The Gauls then seem to have given up on carrying out a frontal attack, and were preparing for a long siege. However, the Gauls attempted a second assault under cover of night. This was apparently thwarted thanks to the sacred geese of Juno, whose cries attracted the attention of Marcus Manlius. The latter prevented the attackers from gaining a foothold on the top of the hill,[19][23] thus earning the nickname "Capitolinus".

During the siege, the young pontifex Gaius Fabius Dorsuo also made a name for himself by not hesitating to leave the refuge of the Capitoline Hills, cross the enemy lines and reach the Quirinal Hill to celebrate a family ceremony there. The Gauls, taken aback by this act of courage and piety, are said to have let him pass.[15] The episodes of Manlius and Fabius Dorsuo are today considered legendary[24] and are an opportunity for ancient authors to involve the gods in the conflict, and to clearly show that they offer their favors to the Romans.[18]

- "Geese Saves Rome", illustration from the book "The story of the greatest nations, from the dawn of history to the twentieth century", 1900.

- "Just in time to repel the first attackers", illustration from the book "Stories from Ancient Rome", Alfred J. Church.

- "The Sack of Rome by the Gauls", François Chifflart, 1863.

The payment of the ransom

After seven months of siege, in the grip of famine, the besieged finally negotiated their surrender in exchange for the payment of a ransom set according to tradition at 1,000 pounds of gold, or 330 kilograms of gold.[12][25] The inglorious nature of this episode is partly attenuated in the traditional account by the greedy and provocative attitude that ancient historians attribute to the Gauls and their leader Brennus.[26] When weighing the ransom, the Gauls are said to have used rigged weights. To the Roman protests, Brennus is said to have responded eloquently by adding his sword to the incriminated weights, justifying the right of the victors with the phrase "Vae victis" (Woe to the vanquished!).[25]

The matrons were forced to sacrifice their jewels in order to pay the ransom, an act which earned them permission to use the heavy cart ("pilentum") during the festivals.[27]

According to the Greek historian Polybius, it was the Gauls who negotiated the lifting of the siege because the Veneti invaded their homelands in Cisalpine Gaul.[28] For Livy, it was an epidemic of plague that forced the Gauls to interrupt the siege and withdraw from Rome.[29]

Modern analysis

It is now accepted that the ancient accounts are based on a meager historical background, limited to the fact that a band of Gauls defeated a Roman army and were able to besiege or even invest the city of Rome. This event would have been amplified by the annalistic record, which would have used it as a backdrop to introduce a whole series of worthy and heroic acts: the sacrifice of the old magistrates, the exceptional piety of the pontiff Caius Fabius Dorsuo or the exploits in battle of Marcus Manlius Capitolinus.[30] The scope of the event and the destruction attributed to the Gauls were amplified to the point of making this disaster "a crisis of cosmic dimensions" calling into question the order of the world.[31]

The limited number of finds of Gallic equipment from the 4th century BC in Italy also casts doubt on the reality of the events described by ancient authors.[32] Traces of fire dating back to this period have indeed been found on the Palatine Hill, but nothing as significant as the burning of an entire city.[33] Destruction on such a scale should have left more traces on monuments of the period such as the Forum or the temples of the area of Sant'Omobono. It seems more likely that the Gauls caused localized destruction, for example by starting fires mainly affecting wooden dwellings. They would have plundered the temples of their valuables to gain booty but would not have destroyed the monuments.[12] The tradition relied on by ancient authors certainly exaggerated the extent of the damage and the Gallic numbers, speaking of "hordes", to attenuate the humiliation suffered by the Romans. Livy uses this supposed total destruction to justify the lack of archives for the first centuries of Rome, but these documents must have been few in number at that time and were certainly kept safe at Caereus or on the Capitol so as not to fall into the hands of the Gauls.[34] For Nicholas Horsfall, "the events of 390 — or rather of 387/6 — are, in the form in which they have been transmitted, an inextricable jumble of etiological narratives, family apologias, doublets and transfers from Greek history."[35] Thus, the name of the Senone leader, Brennus, which only appears from Livy onwards (it does not appear in Polybius or Diodorus Siculus), probably reflects the name of the leader of the Celts who made an incursion into Greece in 280–279.[35]

The Fate of the Roman Ransom

Summarize

Perspective

Livy's version: Camillus' intervention

According to Livius tradition, General Camillus then intervened at the head of his relief army at just the right moment to challenge the legality of the ransom, like a "deus ex machina."[36] The general opposed the granting of the ransom, as it had been established illegally in his absence, and prepared to give battle to the Gauls, who were soon defeated.[37] This intervention by Camillus, where he famously chanted "Non auro, sed ferro, recuperanda est patria" (Our homeland must be recovered, not with gold, but with iron), the providential man, is today considered a lie of the annalistic record allowing the Romans to be exonerated from the shame of having had to bargain for their survival.[36]

Livy also reports a second, "more regular" battle on the road to Gabii, a battle which was also supposedly won by Camillus, massacrinf the total Celtic force, including Brennus.[38] Plutarch, deviating from the version of the Roman historian, disputes the first Roman victory, but he also mentions a battle on the road to Gabii. In this version, the Romans are also victorious, although less completely.[39]

Strabo's version: intervention of Caere

According to Strabo,[40] the booty taken by the Gauls was recovered a few years later by the troops of Caere who intercepted the Gauls of Brennus during an ambush while they were returning from Iapygia.[16] The Romans were then doubly indebted to the Cerites, on the one hand for having sheltered the Roman sacred objects, as well as the vestals and the flamines, and on the other hand for having recovered and returned the important booty taken by the Gauls.[16] Rome expressed its gratitude by granting the inhabitants of Caere extended rights ("hospitium publicum") such as exemption from taxes or military service for Cerites residing in Rome.[41] The two cities concluded a treaty of hospitium which provided social, commercial and military benefits for the inhabitants of one city residing in the other city ("conubium", "commercium", "militia").[42] The Cerites concerned then had the privilege and honor of having their names included in the lists of Roman citizens on special tables, the "cerites tables" ("tabulae Caerites").[36]

The Livii Drusi version

Suetonius, for his part, remembers an older tradition claimed by the family of the Livii Drusi. He states that the Gauls left with the ransom, which was only recovered almost a century later by the propraetor of Cisalpine Gaul, Drusus, during the campaign against the Senones led by Publius Cornelius Dolabella in 283 BC.[36][43]

Modern versions

According to a modern interpretation by Emilio Gabba in contrast with the classical sources, the Gauls withdrew to face the attacks of the Veneti, to the north of their original territories, carrying away the spoils of war.[44]

Concequences

Summarize

Perspective

Impact on history

Following these events, the Romans may have adopted a new type of helmet (the Montefortino helmet, from the name of a necropolis near Ancona, which was used until the 1st century BC by the Roman army),[45] a shield protected by iron edges[46] and a javelin ("pilum") such that it could stick and bend in the opponent's shields, making them unusable for the continuation of the battle.[46] Plutarch tells, in fact, that 13 years after the battle of the Allia river, in a subsequent clash with the Gauls (dating back to 377–374 BC), the Romans managed to defeat the Celtic armies, and stopped a new invasion.[46]

"A lasting trauma"

According to Titus Livius (Livy)[47] and Plutarch,[48] after a seven-month occupation, the city of Rome was completely sacked, destroyed and burned, with the exception of the Capitoline Hill.[12] On the external front, according to Polybius, it took the Romans thirty years to regain the hegemonic position in Latium that they had gained by the capture of Veii in 396 BC.

For the Romans, this event remained anchored in the conscience and became a national trauma. The accounts, notably that of Livy which has the greatest posterity, agree in recognizing the sack of Rome as a defilement of sacred order. In addition to the bad omens reported by the historian before the events, Livy indicates that the dictator Camillus concerned himself above all with rebuilding and purifying the temples, then he had homage paid to the protective gods of the city.[49] The trauma touches the very essence of the Roman nation.

The very existence of the city seemed threatened since shortly after the departure of the Gauls, the tribune of the plebs, supported by the people, defended the idea of transferring the Roman capital from the site of Rome to that of Veii, which was easier to defend. Camillus, leader of the party for reconstruction "in situ" (on the location), had to firmly oppose this idea and ended up convincing the Roman people.[50][51] He earned on this occasion the nickname of "second founder of Rome",[52] raising him to a level equal to that of Romulus.[53]

Rome according to the Greek world

The news of the capture of Rome by the Gauls spread quickly throughout the Greek world, relayed by contemporary authors such as Theopompus and Aristotle.[54] The city of Rome, a city unknown to the Greeks, was suddenly put in the spotlight, to the point of being described as a Greek city by some authors. According to Trogus Pompeius, a Gallo-Roman contemporary of Augustus, Greek cities such as Massĭlĭa even offered financial aid to compensate for the ransom taken by the Gauls.[36]

The fate suffered by the Romans, victims of a Gallic pillaging raid, brought them closer to the Greeks of Delphi, whose sanctuary was also pillaged by the Gauls in 278 BC. These Celtic incursions allowed the Roman and Greek worlds to find a common enemy defining barbarism in contrast to the civilized world that the Romans and Greeks represented and defended.[55]

Conquest of Cisalpine Gaul

The sack of Rome provoked a fear of the Gauls deeply rooted in the collective unconscious,[34] which may partly explain the fact that later, the Romans devoted all their attention to neutralizing the Gallic threat. This desire to repel this threat led to the conquest of Cisalpine Gaul which was completed during the 2nd century BC.

Sources

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.