SABRE (rocket engine)

Synergetic Air Breathing Rocket Engine - a proposed hybrid ramjet and rocket engine From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

SABRE (Synergetic Air Breathing Rocket Engine[4]) was a concept under development by Reaction Engines Limited for a hypersonic precooled hybrid air-breathing rocket engine.[5][6] The engine was designed to achieve single-stage-to-orbit capability, propelling the proposed Skylon spaceplane to low Earth orbit. SABRE was an evolution of Alan Bond's series of LACE-like designs that started in the early/mid-1980s for the HOTOL project.[7] Reaction Engines went into bankruptcy in 2024 before completing the project.[8]

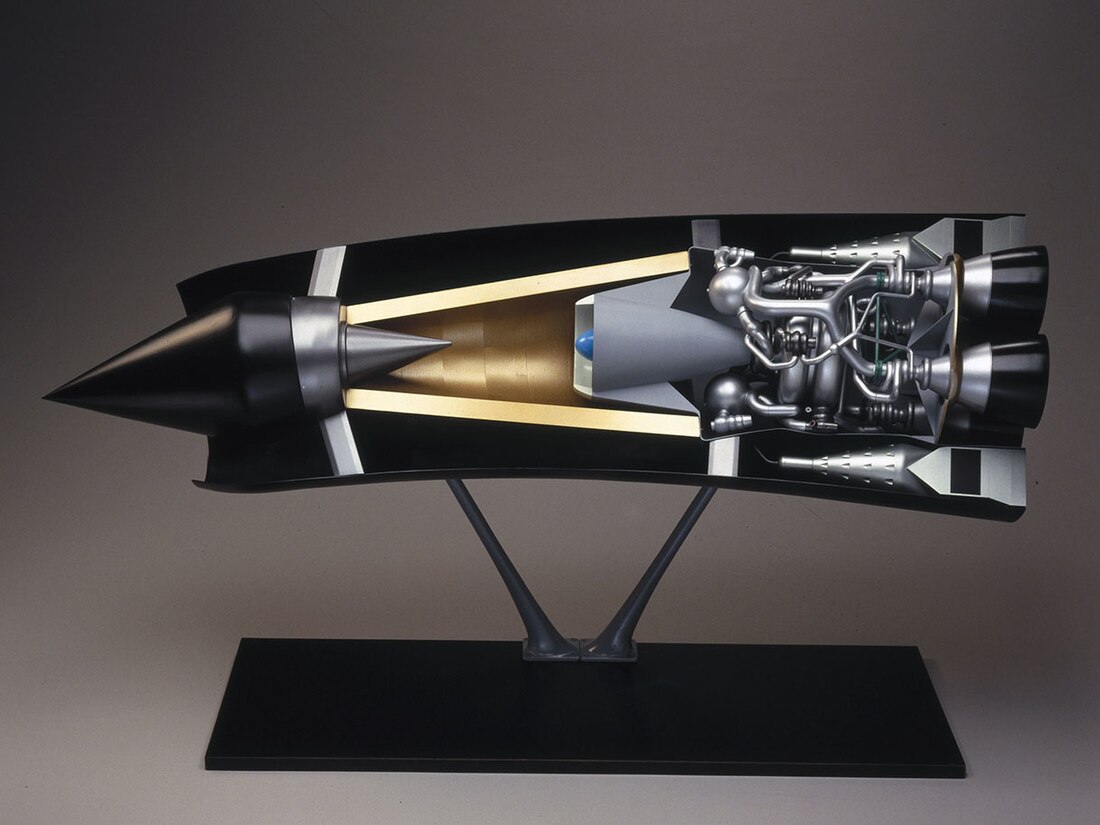

A version of the SABRE engine designed in the 1990s | |

| Country of origin | United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Designer | Reaction Engines Limited |

| Application | Single-stage-to-orbit |

| Associated LV | Skylon |

| Predecessor | RB545 |

| Status | Cancelled at research and development stage |

| Liquid-fuel engine | |

| Propellant | Air or liquid oxygen / liquid hydrogen[1] |

| Cycle | Combined cycle precooled jet engine and closed cycle rocket engine |

| Performance | |

| Thrust, vacuum | Approx. 2,940 kN (660,000 lbf)[citation needed] |

| Thrust, sea-level | Approx. 1,960 kN (440,000 lbf)[citation needed] |

| Thrust-to-weight ratio | Up to 14 (atmospheric)[2] |

| Specific impulse, vacuum | 460 seconds (4.5 km/s)[3] |

| Specific impulse, sea-level | 3,600 seconds (1.0 lb/(lbf⋅h); 35 km/s)[3] |

The design comprised a single combined cycle rocket engine with two modes of operation.[3] The air-breathing mode combined a turbo-compressor with a lightweight air precooler positioned just behind the inlet cone. At high speeds this precooler would cool the hot, ram-compressed air, which would otherwise reach a temperature that the engine could not withstand,[9] leading to a very high pressure ratio within the engine. The compressed air would subsequently be fed into the rocket combustion chamber where it would be ignited along with stored liquid hydrogen. The high pressure ratio would allow the engine to provide high thrust at very high speeds and altitudes. The low temperature of the air would permit light alloy construction to be employed and this allow a very lightweight engine—essential for reaching orbit. In addition, unlike the LACE concept, SABRE's precooler would not liquefy the air, thus letting it run more efficiently.[2]

After shutting the inlet cone off at Mach 5.14, and at an altitude of 28.5 km (17.7 mi),[3] the system would continue as a closed-cycle high-performance rocket engine burning liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen from on-board fuel tanks, potentially allowing a hybrid spaceplane concept like Skylon to reach orbital velocity after leaving the atmosphere on a steep climb.

An engine derived from the SABRE concept called Scimitar has been designed for the company's A2 hypersonic passenger jet proposal for the European Union-funded LAPCAT study.[10]

History

Summarize

Perspective

The precooler concept evolved from an idea originated by Robert P. Carmichael in 1955.[11] This was followed by the liquid air cycle engine (LACE) idea which was originally explored by General Dynamics in the 1960s as part of the US Air Force's aerospaceplane efforts.[2]

The LACE system was to be placed behind a supersonic air intake which would compress the air through ram compression, then a heat exchanger would rapidly cool it using some of the liquid hydrogen fuel stored on board. The resulting liquid air was then processed to separate the liquid oxygen for combustion. The amount of warmed hydrogen was too great to burn with the oxygen, so most was to be expelled, giving useful thrust, but greatly reducing the potential efficiency.[citation needed]

Instead, as part of the HOTOL project, the liquid air cycle engine (LACE) based RB545 engine was developed with more efficient cycle. The engine was given the Rolls-Royce name "Swallow".[12] In 1989, after funding for HOTOL ceased, Bond and several others formed Reaction Engines Limited to continue research. The RB545's precooler had issues with embrittlement and excess liquid hydrogen consumption, and was encumbered by both patents and the UK's Official Secrets Act, so Bond developed SABRE instead.[13]

In 2016 the project received £60m in funds from the UK government and ESA for a demonstrator involving the full cycle.[14] In July 2021 the UK Space Agency provided a further £3.9m for continued development.[15]

Concept

Summarize

Perspective

Like the RB545, the SABRE design was neither a conventional rocket engine nor a conventional jet engine, but a hybrid that used air from the environment at low speeds/altitudes, and stored liquid oxygen at higher altitude. The SABRE engine "relies on a heat exchanger capable of cooling incoming air to −150 °C (−238 °F), to provide oxygen for mixing with hydrogen and provide jet thrust during atmospheric flight before switching to tanked liquid oxygen when in space."

In air-breathing mode, air would enter the engine through an inlet. A bypass system would then direct some of the air through a precooler into a compressor, which would inject it into a combustion chamber where it would be burnt with fuel, the exhaust products then accelerated through nozzles to provide thrust. The remainder of the intake air would continue through the bypass system to a ring of flame holders which act as a ramjet for part of the air breathing flight regime. A helium loop would be used to transfer the heat from the precooler to the fuel and drive the engine pumps and compressors.

Inlet

At the front of the engine, the concept designs proposed a simple translating axisymmetric shock cone inlet which would compress and slow the air (relative to the engine) to subsonic speeds using two shock reflections. Accelerating the air to the speed of the engine would incur ram drag. As a result of the shocks, compression, and acceleration the intake air would be heated, reaching around 1,000 °C (1,830 °F) at Mach 5.5.

Bayern-Chemie, through ESA, had undertaken work to refine and test the intake and bypass systems[16]

Precooler

As the air would enter the engine at supersonic or hypersonic speeds, it would become hotter than the engine can withstand due to compression effects.[9] Jet engines, which have the same problem but to a lesser degree, solve it by using heavy copper or nickel-based materials, by reducing the engine's pressure ratio, and by throttling back the engine at the higher airspeeds to avoid melting. However, for a single-stage-to-orbit (SSTO) spaceplane, such heavy materials are unusable, and maximum thrust is necessary for orbital insertion at the earliest time to minimise gravity losses. Instead, using a gaseous helium coolant loop, SABRE would dramatically cool the air from 1,000 °C (1,830 °F) down to −150 °C (−238 °F) in a counterflow heat exchanger while avoiding liquefaction of the air or blockage from freezing water vapour. The counterflow heat exchanger would also allow the helium to exit the engine at a sufficiently high temperature to drive pumps and compressors for the liquid hydrogen fuel and helium working fluid itself.

Previous versions of precoolers such as HOTOL put the hydrogen fuel directly through the precooler. SABRE would insert a helium cooling loop between the air and the cold fuel to avoid problems with hydrogen embrittlement in the precooler.

The dramatic cooling of the air created a potential problem: it would be necessary to prevent blocking the precooler from frozen water vapour and other air fractions. In October 2012, the cooling solution was demonstrated for 6 minutes using freezing air.[17] The cooler would consist of a fine pipework heat exchanger with 16,800 thin-walled tubes,[18] and would cool the hot in-rushing atmospheric air down to the required −150 °C (−238 °F) in 0.01 s.[19] The ice prevention system had been a closely guarded secret, but REL disclosed a methanol-injecting 3D-printed de-icer in 2015 through patents, as they needed partner companies and could not keep the secret while working closely with outsiders.[20][21][22]

Compressor

Below five times the speed of sound and 25 kilometres of altitude, which are 20% of the speed and 20% of the altitude needed to reach orbit, the cooled air from the precooler would pass into a modified turbo-compressor, similar in design to those used on conventional jet engines but running at an unusually high pressure ratio made possible by the low temperature of the inlet air. The compressor would feed the compressed air at 140 atmospheres into the combustion chambers of the main engines.[23]

In a conventional jet engine, the turbo-compressor is driven by a gas turbine powered by combustion gases. SABRE would drive the turbine with a helium loop, which would be powered by heat captured in the precooler and a preburner.[23]

Helium loop

The 'hot' helium from the air precooler would be recycled by cooling it in a heat exchanger with the liquid hydrogen fuel. The loop would formsm a self-starting Brayton cycle engine, cooling critical parts of the engine and powering turbines.[citation needed] The heat would pass from the air into the helium. This heat energy would then be used to power various parts of the engine and to vaporise hydrogen, which would then be burnt in ramjets.[3][24]

Combustion chambers

The combustion chambers in the SABRE engine would be cooled by the oxidant (air/liquid oxygen) rather than by liquid hydrogen[25] to further reduce the system's use of liquid hydrogen compared with stoichiometric systems.

Nozzles

The most efficient atmospheric pressure at which a conventional propelling nozzle works is set by the geometry of the nozzle bell. While the geometry of the conventional bell remains static the atmospheric pressure changes with altitude and therefore nozzles designed for high performance in the lower atmosphere lose efficiency as they reach higher altitudes. In traditional rockets this is overcome by using multiple stages designed for the atmospheric pressures they encounter.

The SABRE engine would have to operate at both low and high altitude scenarios. To ensure efficiency at all altitudes a sort of moving, expanding nozzle would be used. First at low altitude, air-breathing flight the bell would be located rearwards, connected to a toroidal combustion chamber surrounding the top part of the nozzle, together forming an expansion deflection nozzle. When SABRE later transitions into rocket mode, the bell would be moved forwards, extending the length of the bell of the inner rocket combustion chamber, creating a much larger, high altitude nozzle for more efficient flight.[26]

Bypass burners

Avoiding liquefaction would improve the efficiency of the engine since less entropy would be generated and therefore less liquid hydrogen would be boiled off. However, simply cooling the air would need more liquid hydrogen than could be burnt in the engine core. The excess would be expelled through a series of burners called "spill duct ramjet burners",[3][24] that would be arranged in a ring around the central core. These would be fed air that bypasses the precooler. This bypass ramjet system was designed to reduce the negative effects of drag resulting from air that would pass into the intakes but would not be fed into the main rocket engine, rather than generating thrust. At low speeds the ratio of the volume of air entering the intake to the volume that the compressor could feed to the combustion Chambers would be at its highest, requiring the bypassed air to be accelerated to maintain efficiency at these low speeds. This distinguished the system from a turboramjet where a turbine-cycle's exhaust is used to increase air-flow for the ramjet to become efficient enough to take over the role of primary propulsion.[27]

Development

Summarize

Perspective

Tests were carried out in 2008 by Airborne Engineering Ltd on an expansion deflection nozzle called STERN to provide the data needed to develop an accurate engineering model to overcome the problem of non-dynamic exhaust expansion. This research continued with the STRICT nozzle in 2011.

Successful tests of an oxidiser (both air and oxygen) cooled combustion chamber were conducted by EADS-Astrium at Institute of Space Propulsion in 2010.

In 2011, hardware testing of the heat exchanger technology "crucial to [the] hybrid air- and liquid oxygen-breathing [SABRE] rocket motor" was completed, demonstrating that the technology is viable.[28][29] The tests validated that the heat exchanger could perform as needed for the engine to obtain adequate oxygen from the atmosphere to support the low-altitude, high-performance operation.[28][29]

In November 2012, Reaction Engines announced it had successfully concluded a series of tests that prove the cooling technology of the engine, one of the main obstacles towards the completion of the project. The European Space Agency (ESA) evaluated the SABRE engine's precooler heat exchanger, and accepted claims that the technologies required to proceed with the engine's development had been fully demonstrated.[28][30][31]

In June 2013 the United Kingdom government announced further support for the development of a full-scale prototype of the SABRE engine,[32] providing £60M of funding between 2014 and 2016[33][34] with the ESA providing an additional £7M.[35] The total cost of developing a test rig was estimated at £200M.[33]

By June 2015, SABRE's development continued with The Advanced Nozzle Project at Westcott. The test engine, operated by Airborne Engineering Ltd., was used to analyze the aerodynamics and performance of the advanced nozzles that the SABRE engine would use, in addition to new manufacturing technologies such as the 3D-printed propellant injection system.[36]

In April 2015, the SABRE engine concept passed a theoretical feasibility review conducted by the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory.[37][38][39] The laboratory was to reveal two-stage-to-orbit SABRE concepts shortly afterwards, as they considered that a single-stage-to-orbit Skylon space plane was "technically very risky as a first application of SABRE engine".[40]

In August 2015 the European Commission competition authority approved UK government funding of £50 million for further development of the SABRE project. This was approved on the grounds that money raised from private equity had been insufficient to bring the project to completion.[41] In October 2015 British company BAE Systems agreed to buy a 20% stake in the company for £20.6 million as part of an agreement to help develop the SABRE hypersonic engine.[42][43] In 2016, Reaction CEO Mark Thomas announced planned to build a quarter-sized ground test engine, given limitations of funding.[44]

In September 2016 agents acting on behalf of Reaction Engines applied for planning consent to build a rocket engine test facility at the site of the former Rocket Propulsion Establishment in Westcott, UK[45] which was granted in April 2017,[46] and in May 2017 a groundbreaking ceremony was held to announce the beginning of construction of the SABRE TF1 engine test facility, expected to become active in 2020.[47][48] However, development of the TF1 facility was since quietly dropped, and the site was taken on by aerospace and defence group Nammo.[49]

In September 2017 it was announced the United States Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) had contracted with Reaction Engines Inc. to build a high-temperature airflow test facility at Front Range Airport near Watkins, Colorado.[50] The DARPA contract was to test the Sabre engine's pre-cooler heat exchanger (HTX). Construction of the test facilities and test articles began in 2018 with testing focusing on running the HTX at temperatures simulating air coming through a subsonic intake travelling at Mach 5 or around 1,800 °F (1,000 °C) beginning in 2019.[51][52]

The HTX test unit was completed in the UK and sent to Colorado in 2018, where on 25 March 2019 an F-4 GE J79 turbojet exhaust was mixed with ambient air to replicate Mach 3.3 inlet conditions, successfully quenching a 420 °C (788 °F) stream of gases to 100 °C (212 °F) in less than 1/20 of a second. Further tests simulating Mach 5 were planned, with temperature reduction expected from 1,000 °C (1,830 °F).[9][18] These further tests were successfully completed by October 2019.[53][54][55]

The successful HTX test was thought to maybe lead to spin-off precooler applications which could be developed before a scalable SABRE demonstrator was completed; suggested uses were to expand gas turbines capabilities, in advanced turbofans, hypersonic vehicles, and industrial applications.[56] In March 2019, the UKSA and ESA preliminary design review of the demonstrator engine core confirmed the test version to be ready for implementation.[57]

In 2019, Airborne Engineering conducted a test campaign on subscale air/hydrogen injectors for the SABRE preburners.[58]

In 2020, Airborne Engineering conducted a test campaign on an "HX3 module" (preburner to helium loop heat exchanger).[59]

In 2022, a Foreign Comparative Testing of Reaction’s precooler heat exchanger was performed. The testing was successfully completed by the company’s US subsidiary (Reaction Engines Incorporated – REI) and the US Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL). “The FCT test program greatly expanded the demonstrated capabilities of our engine precooler technology”, said REI’s director of engineering, Andrew Piotti. “During these recent tests, the precooler successfully achieved our objective of over 10 megawatts of transferred thermal energy from the high-temperature airflow, which is three times higher than our previous test program.”[60]

Engine

Due to the static thrust capability of the hybrid rocket engine, the vehicle could take off under air-breathing mode, much like a conventional turbojet.[3] As the craft would ascend and the outside air pressure drop, more and more air would be passed into the compressor as the effectiveness of the ram compression drops. In this fashion the jets would be able to operate to a much higher altitude than would normally be possible.

At Mach 5.5 the air-breathing system would become inefficient and would be powered down, replaced by the on-board stored oxygen which would allow the engine to accelerate to orbital velocities (around Mach 25).[23]

Evolution

RB545

Designed for use with HOTOL.

The engine had no air-breathing static thrust capability, relying on a rocket trolley to achieve takeoff.

SABRE

Designed for use with Skylon A4.

The engine had no air-breathing static thrust capability, relying on RATO engines.

SABRE 2

Designed for use with Skylon C1.

The engine had no static thrust capability, using LOX until the air-breathing cycle could take over.[citation needed]

SABRE 3

Designed for use with Skylon C2.

This engine included a fuel rich preburner to augment the heat recovered from the airstream used to drive the helium loop, giving the engine static thrust capability.

SABRE 4

SABRE 4 was no longer a single engine design, but a class of engines, e.g. a 0.8–2 MN (180,000–450,000 lbf; 82–204 tf) instance of this engine would have been used with SKYLON D1.5, a 110,000–280,000 lbf (0.49–1.25 MN; 50–127 tf) for a USAF study into a partially reusable TSTO.

Performance

Summarize

Perspective

The designed thrust-to-weight ratio of SABRE is fourteen compared to about five for conventional jet engines, and two for scramjets.[5] This high performance is a combination of the denser, cooled air, requiring less compression, and, more importantly, the low air temperatures permitting lighter alloys to be used in much of the engine. Overall performance is much better than the RB545 engine or scramjets.

Fuel efficiency (known as specific impulse in rocket engines) peaks at about 3500 seconds within the atmosphere.[3] Typical all-rocket systems peak around 450 seconds and even "typical" nuclear thermal rockets at about 900 seconds.

The combination of high fuel efficiency and low-mass engines permits an SSTO approach, with air-breathing to Mach 5.14+ at 28.5 km (94,000 ft) altitude, and with the vehicle reaching orbit with more payload mass per take-off mass than just about any non-nuclear launch vehicle ever proposed.[citation needed]

The precooler adds mass and complexity to the system and is the most aggressive and difficult part of the design, but the mass of this heat exchanger is an order of magnitude lower than has been achieved previously. The experimental device achieved heat exchange of almost 1 GW/m3. The losses from carrying the added weight of systems shut down during the closed cycle mode (namely the precooler and turbo-compressor) as well as the added weight of Skylon's wings are offset by the gains in overall efficiency and the proposed flight plan. Conventional launch vehicles such as the Space Shuttle spend about one-minute climbing almost vertically at relatively low speeds; this is inefficient but optimal for pure-rocket vehicles. In contrast, the SABRE engine permits a much slower, shallower climb (thirteen minutes to reach the 28.5 km transition altitude), while breathing air and using its wings to support the vehicle. This trades gravity drag and an increase in vehicle weight for a reduction in propellant mass and a gain from aerodynamic lift increasing payload fraction to the level at which SSTO becomes possible.

A hybrid jet engine like SABRE needs only reach low hypersonic speeds inside the lower atmosphere before engaging its closed cycle mode, whilst climbing, to build speed. Unlike ramjet or scramjet engines, the design is able to provide high thrust from zero speed up to Mach 5.4,[4] with excellent thrust over the entire flight, from the ground to very high altitude, with high efficiency throughout. In addition, this static thrust capability means the engine can be realistically tested on the ground, which drastically cuts testing costs.[5]

In 2012, REL expected test flights by 2020, and operational flights by 2030.[61]

See also

- Altitude compensating nozzle

- Avatar (spacecraft) – India's air-breathing spaceplane

- Liquid-propellant rocket

- Precooled jet engine

References

Resources

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.