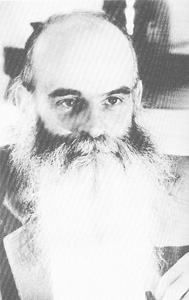

Ronald Gene Simmons

American mass murderer (1940–1990) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Ronald Gene Simmons Sr. (July 15, 1940 – June 25, 1990) was an American mass murderer and retired military serviceman who, over a week in December 1987, killed 16 people, including 14 family members, in Arkansas, marking the deadliest familicide in U.S. history. Born in Chicago, Simmons served over 20 years in the U.S. Navy and Air Force before descending into a life of isolation and abuse, culminating in a rampage that ended with his execution by lethal injection in 1990—the first such execution in Arkansas. Despite the scale of his crimes, Simmons offered no clear motive, refused appeals, and sought a swift death penalty, leaving his reasons largely a mystery.

Ronald Gene Simmons | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 15, 1940 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | June 25, 1990 (aged 49) Cummins Unit, Arkansas, U.S. |

| Criminal status | Executed by lethal injection |

| Spouse | Bersabe Rebecca "Becky" Ulibarri (m. July 9, 1960) |

| Children | 7 |

| Convictions | Capital murder (two trials, 16 victims) |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

| Details | |

| Date | December 22–28, 1987 |

| Country | United States |

| Locations | Rural Pope County and Russellville, Arkansas |

| Killed | 16 |

| Injured | 4 |

| Weapons |

|

Ronald Gene Simmons | |

|---|---|

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service | US Navy (1957–62) US Air Force (1963–1979) |

| Years of service | 1957–1962 (USN) 1963–1979 (USAF) |

| Rank | Master sergeant (USAF) |

| Awards | Bronze Star Medal Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross Airforce Ribbon for Excellent Marksmanship |

A retired military serviceman, Simmons murdered fourteen members of his family, including a daughter he had sexually abused and the child he had fathered with her, as well as a former co-worker, and a stranger; he also wounded four others.[1]

Simmons holds the grim distinction of being the deadliest mass murderer in Arkansas history.[2]

Simmons was sentenced to death in two separate trials and refused to appeal either. His refusal to appeal was the subject of a 1990 US Supreme Court case, Whitmore v. Arkansas.

Simmons was executed on June 25, 1990, one year and four and a half months after the second conviction. Only one other murderer, Gary Gilmore, had a shorter time from sentence to execution in the modern era of capital punishment.[3]

Personal life and military career

Summarize

Perspective

Ronald Gene Simmons was born to Loretta and William Simmons on July 15, 1940, in Chicago, Illinois, their second son. A sister, Nancy Ellen Simmons Madden (February 4, 1942 – April 30, 2004), was born seventeen months later.[4] On January 31, 1943, William Simmons died of a stroke. Within a year, Simmons's mother had remarried, this time to William D. Griffen, a civil engineer for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, with a new son, Peter, arriving soon thereafter. In 1946, the corps moved Griffen to Little Rock, Arkansas, the first of several transfers that would take the family across central Arkansas over the next decade. Some of that time, the family lived in Pope County, near Hector.[5]

By age 10, Simmons was known as the family bully, frequently tormenting his younger sister, Nancy, and half-brother, Pete, who said after the murders that Simmons had heaped the same abuse on his own children.[6] A relative noted he exploited any weakness relentlessly. He also lashed out at animals, repeatedly hitting a family cat until it turned aggressive. A sister-in-law later described him as egocentric, universally resentful, and quick to blame others, often erupting in anger.[4] Gene's behavioral issues persisted despite his parents' efforts to address them. For several summers, they sent him to live with a nearby friend to separate him from his siblings. Additionally, they enrolled him in the Morris School for Boys, a Roman Catholic boarding school near Searcy.[7]

On September 5, 1957, Simmons dropped out of school and enlisted in the United States Navy. In November of that year, he was stationed at a ship repair facility in Guam, where he successfully earned his General Equivalency Diploma (GED). In July 1959, Simmons, then a Yeoman Third Class, was assigned to Naval Hospital Bremerton at Naval Station Bremerton in Washington. While there, he attended a USO dance at the Bremerton YMCA, where he met Bersabe Rebecca "Becky" Ulibarri.[8]

The couple was married in Raton, New Mexico, on July 9, 1960. Over the next 18 years, the couple had seven children.[9]

On July 13, 1962, Simmons left the Navy, and, on January 30, 1963, joined the U.S. Air Force. Stationed at Langley Air Force Base, the couple's first child, Shiela, was born on October 24.[8]

He was eventually assigned to the Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI) and, in January 1966, was promoted to Staff Sergeant. The following year, Simmons reenlisted and volunteered for a tour in Vietnam in return for a guarantee of a billet with AFOSI in Saigon. Before the transfer to Saigon, he was assigned to the AFOSI Personnel Investigations Division. Landing at Tan Son Nhut Air Base on August 2, 1967, Simmons was in Vietnam until July 1968, including the early 1968 Tet Offensive when Saigon was attacked.[9]

During his over 20-year administrative specialist military career, Simmons was awarded a Bronze Star Medal,[10] the Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross,[11][12] and the Air Force Small Arms Expert Marksmanship Ribbon. Simmons retired from the Air Force and military service on November 30, 1979, with the rank of master sergeant. Simmons' service record was spotless and his performance marks were often exemplary. Simmons's career in the Air Force was primarily clerical.[9]

Dominance and Control

Becky confided in her sister that Simmons's mother had warned her about his temper and tendency to dominate those close to him. "She was always trying to tell me what Gene was like," Becky told her sister. "But I didn't listen."[4]

At Simmons' insistence, Becky stopped wearing makeup and kept her hair tied back. He handled all household tasks, like bills and groceries, and forbade her from getting a driver's license or using a phone. She could only write to her family, but later, he denied her stamps, forcing her to ask others to mail her letters secretly. Simmons used distant post office boxes to censor the family's mail and required Becky to wear long dresses. Her sister noted, "Becky was not stupid by any means, but she was insecure. Ronald had made her believe that things were her fault, that she deserved what she got."[4] "He cut her off from all of us and now he's gone crazy... He wouldn't let her have a telephone and he'd stand there if she ever made any calls from somewhere else."[13]

Just before Simmons was executed in June 1990, Becky's brother, Manuel Ulibarri, described him as an evil man who demanded complete control of his family.[14]

New Mexico

From 1976 to 1981, the family lived on a 2-acre (0.81 ha) property in Wills Canyon near the small town of Cloudcroft, New Mexico.[9]

In April 1976, after a four-year stint in the UK stationed at RAF Alconbury,[8] Air Force Master Sergeant R. Gene Simmons was assigned to the Space and Missile Systems Organization (SAMSO) observatory high in the Sacramento Mountains east of Alamogordo. The SAMSO Electro-Optical Research Facility focused its telescopes on Air Force communications satellites and detectors on high-flying aircraft. Located thirty-two miles from Holloman AFB, the observatory was a semiautonomous post with a personnel roster of one officer and seven enlisted personnel, with Simmons being the senior enlisted man. All had top security clearances.[9]

In November 1976, the Air Force announced that the observatory would be placed on "caretaker status" as soon as possible. As the staff numbers at the site decreased, Simmons took on more responsibilities and ultimately was the last person to "turn out the lights" when the observatory was deactivated in June 1978. After this, Simmons was transferred to the 6585th Test Group at Holloman Air Force Base near Alamogordo.[9]

On November 30, 1979,[8] Simmons, who had over 20 years of service, retired from the Air Force when faced with the possibility of a promotion to Senior Master Sergeant (E-8) that would require extending his service obligation and a transfer to Turkey.[9][15]

On May 5, 1981, Simmons began working as a GS-4 civil service employee at Holloman AFB.[9]

Allegations, investigation, and charges

In 1981, Simmons was investigated for allegations of child sex abuse and for allegedly impregnating his 17-year-old daughter, Sheila. Social Services had been alerted anonymously on April 17, 1981.[16] The district attorney at the time, Steven Sanders, stated that Simmons' son, R. Gene Simmons Jr., revealed to him that he was the informant.[17] The son called two more times in the next three days, again anonymously. Additionally, authorities learned of the allegations through friends of Sheila who had been told about the situation and from school officials.[18]

On April 20, a caseworker went to Cloudcraft to investigate rumors. Meeting privately, Sheila confirmed the suspicions that she was pregnant with her father's child.[15][19]

An assistant Otero County prosecutor was notified on April 21. Under threat of prosecution, Simmons eventually agreed to a program of psychological counseling for the whole family.[15]

According to authorities, the initial incest had occurred in July 1980, in a hotel room in Phoenix when Simmons and Sheila were on their way from New Mexico to California for a coin show. While Simmons loved coin collecting, Sheila only pretended to enjoy it to please him.[15]

According to social workers' investigations, at least two more occurrences occurred in September 1980.[20] In March 1981, Sheila recognized she was pregnant and told her father. She gave birth to a daughter, Sylvia, on June 17, 1981.[15][9]

A 1981 New Mexico Social Services report says that social workers tried to get legal custody of R. Gene Simmons' four daughters after he insisted the family would raise the child he fathered with the eldest daughter.[21] The report, dated June 8, 1981, asked District Attorney Sanders to seek a court order for custody of the children. Sanders later claimed an assistant district attorney never relayed the request to him.[22]

Simmons and his family attended counseling for five weeks in 1981,[15] but they stopped in June after their lawyer informed Simmons that anything he disclosed to social workers could be used against him in court. Once the counseling sessions ended, a criminal investigation began. On June 19, the District Attorney's office referred the case to the sheriff for further investigation.[23]

Deputy Jeff Farmer drove to the Simmons property on June 20, 1981, where he met Sheila Simmons and her mother Becky. Sheila refused to make any statement or comment. On July 6, school principal Everett Banister, who lived near the Simmons family, told Farmer that he took assignments to Sheila at home and made arrangements for her final exams.[24]

Banister said he didn't discuss the allegations with the family because social workers were handling the case. He said he took classwork to the Simmons home so she could graduate at the end of May and that the mother and her children were friendly, but Simmons was strange.[24] He couldn't recall ever talking to Simmons, but he did remember seeing him and his daughter Sheila riding down the road once. "She was sitting so close to him, like boyfriend-girlfriend instead of father-daughter." Others made similar observations.[25]

Farmer's investigation ended July 11, 1981, after Farmer met with R. Gene Simmons Jr. Farmer said the younger Simmons would not talk about the incest allegation because his sister and mother asked him not to, but that the family was "well-satisfied" with its counseling session.[24]

Former DA Sanders said Sheila Simmons ignored a grand jury subpoena and refused to discuss the incest with investigators until Sanders threatened her with contempt of court.[17] Sheila reluctantly appeared on August 10[26] and testified against her father, telling the jurors that her father had intimate relations with her three times. Sanders said, "She testified for two hours... She broke down and cried. She said she didn't want her father to go to prison."[27] Sheila's statements eventually led to a criminal charge and an arrest warrant.[28][29]

On August 11, 1981, in Otero County, New Mexico, two months after Sheila gave birth to a daughter,[30] Simmons was charged in New Mexico's 12th Judicial District, with engaging in incest three times in September 1980 and could have faced up to nine years in prison if convicted.[31][17] Sheriff's deputies planning to arrest Simmons arrived at the home 20 miles outside of Cloudcroft on August 11 to find the family had packed and moved away.[32][33]

Abe DeLeon, Otero County manager for the New Mexico Human Services Department said he received an anonymous tip that the Simmons family had gone to the Little Rock area. DeLeon then sent a "protective Service alert" about Simmons to the Arkansas Human Service Department on March 17, 1982. Walt Patterson, deputy director of the Arkansas Human Services Department, said there was no reason for the department to act on an alert from New Mexico. The proper way to handle that would have been through law enforcement agencies, who might have traced Simmons through his military pension payments. Patterson also said, "if we had been contacted by the Simmons family, we would have taken action on the New Mexico alert."[34]

Former DA Steven Sanders said he met with R. Gene Simmons Jr. in June or July 1982. Simmons said he did not know where his father lived but that he could have him returned to New Mexico if the charges were dropped.[24]

The New Mexico incest charges were conditionally dismissed on August 10, 1982.[32][35] Former DA Sanders said the indictment was dismissed because officials had been unable to locate the family and the only witness was the uncooperative daughter. The dismissal had a provision allowing reinstatement of the charges if Simmons was arrested.[24] The dismissal canceled the arrest warrant and any information stored on the FBI's National Crime Information Center (NCIC) was dropped, leaving no trace.[36]

Arkansas

Fearing arrest, Simmons fled with his family, first to Ward, Arkansas, where starting September 30, 1981, he worked as a temporary filing clerk in the medical records division of the John L. McClellan Memorial Veterans Hospital, North Little Rock Division. On January 10, 1982, he left for a permanent personnel clerk position at the 5th Army Medical Recruiting Battalion's Little Rock office.[37][38][5]

Family life had nearly collapsed entirely for Simmons. Gene Jr. declined to relocate to Arkansas, opting instead to remain in New Mexico with high school friends. Following the incest allegations, Becky ceased sharing a bed with her husband.[4]

While in Ward, Simmons impregnated Sheila a second time, the pregnancy aborted this time by Dr. Chu Iy Tan in Dermott in early 1983.[9]

Purchasing a small "farm too far from Little Rock to commute" on June 12, 1983, the family took up residence on a 14-acre (5.7 ha) tract of land[39][40] in Pope County, 6.5 miles (10.5 km) north of Dover that they would dub "Mockingbird Hill."[9][41] He quit the recruiting office job on August 5, 1983.[37]

Friends and family noted that the relocation was influenced by an emerging relationship between Simmons' daughter, Sheila, and a young man named Dennis McNulty. Simmons had enrolled Sheila at the Draughon School of Business, blocks from the recruiting command where he was employed. Shiela and Dennis met in early 1983 at the school's snack bar. While Dennis was studying radio communications, Sheila pursued secretarial courses to secure a job and gain independence from her parents' home. However, the Simmons family's move to Pope County didn't stop McNulty. He regularly drove 170 miles round trip to court Sheila.[4][9]

The Simmons property was 0.25 miles (0.40 km) east of Arkansas Highway 7 on a low ridge parallel to Broomfield Road, a paved county road that traversed a part of Pope County with few paved roads during the 1980s. The property was located in Pleasant Grove, an unincorporated community north of Dover, which had little else nearby except for a church, a cemetery, a corner store, and a campground.[42]

Two days after the family moved in, a "No trespassing" sign went up at the bottom of the road and a barbed wire fence came soon after.[43]

The property featured a five-bedroom mobile home, with two bedrooms under an extended roof. The spacious family room included a fireplace, while the kitchen, dining room, and bedrooms were relatively small.[40][42][44] The home heating and air conditioning system was inoperable. The only heat came from a wood-burning stove in the family room;[45] only one room had a window air conditioner.[9] There was a phone, but Simmons wouldn't let it be hooked up because he didn't want the family to have uncontrolled outside contact.[46] The family used two nearby outhouses because the toilet was broken.[47] The home was surrounded by a makeshift privacy fence that was as high as 10 feet tall in some places. Several weeks before Christmas, Simmons had ordered his family to dig a new privy pit, which would eventually be where he disposed of some of their bodies.[48][9]

While reconciling with Wilma, his estranged wife, Gene Jr. decided to have their three-year-old daughter, Barbara, temporarily spend time at his parents' house until Gene Jr. and Wilma could afford a new place. They planned to reunite and remarry in February 1988. Gene Jr. had arrived at Mocking Bird Hill on December 21. Wilma stayed in New Mexico for Christmas [42] because she couldn't afford to travel to Arkansas for the visit.[49]

Even at home, Simmons was a recluse who spent much of his time at home in his room alone.[50] According to Edith Nesby, Becky's sister, "No one was allowed in his bedroom, not even Becky. He locked the door when he was in it, he locked the door when he was gone."[4]

He was described variously as a reclusive loner,[51] a quiet and stingy man, an unsmiling man with a piercing stare[43] who compelled his children to perform heavy labor, such as carrying five-gallon containers of dirt to maintain a steep driveway. Loretta Simmons, 17, described her father as a "drunken bum" to a school classmate who occasionally stayed overnight and who said Simmons "had a beer in his hand all the time. He had one little room he would stay in all the time. It was dark and seemed spooky and it stunk. Nobody ever went in there but him."[52] It was the only room with an inside lock and had always been off-limits to the children.[9]

In Pope County, Simmons worked a string of low-paying jobs, going from an "industrial" cleaner's job at a pickle plant in Atkins to a "processor" job at a frozen food plant in Russellville and, then, part-time clerk on the nightshift at a Sinclair Mini Mart.[9][43] From January 1985 to November 19, 1986, Simmons worked as a clerk at Woodline Motor Freight, processing checks and making telephone calls to customers who were past due in payment of their bills. According to Robert Wood, president of the company, Simmons quit under pressure to raise his performance level to that of the other clerks. Joyce Butts, who he later shot, was his immediate boss. Kathy Kendrick, who he killed, had been a co-worker at Woodline[53] who reportedly had rejected Simmons' affections.[5][41][42] He worked weekend night shifts at the Mini Mart[9] for approximately three and a half years[54] before quitting on December 18, 1987.[55]

The number of people in the home had decreased to six. Gene Jr.—"Little Gene"—moved out before the family left New Mexico, later marrying Wilma Sue Pitts in Alamogordo on February 28, 1984. Sheila married Dennis McNulty on August 11, 1984, and moved to Camden, taking her daughter, Sylvia. William moved out after securing full-time hours at Hardee's in Russellville (where he had made shift manager) in 1984. He married Renata May in October 1985, and the couple moved to Fordyce. The fourth oldest child, Loretta, was an honors student in the senior class at Dover High School.[56] Set to graduate the following spring, she had made little effort to hide her desire to leave home at her first opportunity.[9][42][46]

Christmas cards

Becky Simmons had sent Christmas cards, each with a letter enclosed, to her siblings. Her sister, Edithe Nesby, said, "She was very happy. Her whole family was coming to see her." She was to have all of her children and grandchildren with her during the Christmas holiday.[57]

Weapons

Simmons owned three weapons. In 1968, when stationed with Air Force OSI in San Francisco, he had purchased a long-barreled Ruger .22-caliber revolver and a Winchester .243-caliber rifle, which was still in its box in 1987. On May 5, 1984, he bought a snub-nose Harrington & Richardson revolver at the Walmart store in Russellville. He took the two pistols with him on his December 1987 rampage in Russellville.[9]

Murders

Summarize

Perspective

Simmons' violent murders occurred in three phases. Two were at the Simmons home and the third was in Russellville on the first workday after the Christmas weekend.

Simmons' home (near Dover)

Investigators later concluded that, in the weeks leading up to the 1987 Christmas holiday, Simmons made a calculated decision to methodically kill all members of his immediate family. He recognized it as the one time they would gather together in a short period. Several weeks earlier, he had instructed his children to dig a large hole, telling them it was for a new outhouse.

December 22, 1987

On the morning of December 22, he first killed his wife Becky and eldest son Gene by bludgeoning them [58] and shooting them with a .22-caliber pistol.[59] He then killed his three-year-old granddaughter Barbara by strangulation.

Simmons dumped the bodies in a pit he had forced his children to dig for a new outhouse almost two months earlier.[60]

Simmons then waited for his other children to return from school for Christmas break. Investigators believed the Simmons children, Loretta, Eddy, Marianne, and Becky (ages seventeen, fourteen, eleven, and eight) were separated and that each was strangled. It was thought that each child's head was held under water in a trash barrel that Simmons had placed in the nonfunctional bathroom and filled to make sure they were no longer breathing. The four children were subsequently dumped in the pit with the other bodies.[42][48]

They were all wearing school clothes. Eddie had a lunch ticket in a pocket. The girls still had barrettes in their hair, and one of them had gum in her mouth.[61] According to the autopsy, Loretta may have struggled trying to escape. Cuts on her face were consistent with being punched at least twice. Her watch and one of her earrings were broken.[42][62]

After he killed the family that had been living at home, Simmons made plans for what he was going to do in Russellville on Monday after the holiday weekend, got drunk and went around the house beating holes in the sheet rock walls and ceiling.[59]

December 26, 1987

Around mid-day on December 26, the remaining family members arrived at the home, as Simmons had invited them over for the holidays. It would have been the first time that the entire family had been together at the same time.

The first to be killed was Simmons' son Billy and his wife Renata, who were both shot dead. He then strangled and drowned their 20-month-old son, Trae. Simmons also shot and killed his oldest daughter, Sheila (whom he had sexually abused), and her husband, Dennis McNulty. Simmons then strangled his child by Sheila, seven-year-old Sylvia Gail, and finally, his 21-month-old grandson Michael. Simmons laid the bodies of his whole family in neat rows in the lounge. Their bodies were covered with coats except that of Sheila, who was covered by Becky Simmons' best tablecloth. The bodies of Trae and Michael were wrapped in plastic sheeting and left in abandoned cars at the end of the lane.

The older six relatives had been shot as many as seven times each.[63][59]

After the murders, Simmons drove to a Sears store in Russellville, where he retrieved Christmas gifts that he had previously ordered for his family.[64] That night, he went for a couple of $2.50 drinks at North 40, a private club in Russellville—Pope County being a dry county, alcoholic beverages were only available in "private" clubs—before returning home.[48][4]

Russellville

On the morning of December 28, the first Monday after Christmas, Simmons wrote a short letter, stuck it in an envelope with $250, and addressed it to his mother-in-law, May Novak. "Dear Ma, sometimes you reap many more times what you sow. This is just a little token of our appreciation. Keep it in remembrance of us. Love, Gene." [65]

Then, armed with two .22-caliber revolvers,[51] Simmons drove a copper-colored Toyota Corolla[9] belonging to his oldest son, Ronald Gene Simmons Jr., to Russellville.

Simmons had meticulously mapped out his murderous route in town.[65] At some point along it, he mailed the letter and two other letters with almost identical wording and money to two nieces. All had a December 28, 1987, Russellville postmark.[8]

Law office

His first target was Kathy Cribbins Kendrick at Peel, Eddy, and Gibbons Law Firm, near the town center on South Glenwood Avenue.[66] Simmons had been infatuated with Kendrick when they both worked at Woodline Motor Freight Company, but she had rejected him. After walking into the office, he shot and killed Kendrick with four shots to the head. She died a short time later at St. Mary's Regional Medical Center.[67]

As he left, someone called the police department. It was about 10:17 AM. There was one dispatcher on duty.[65] There was also a separate Pope County Sheriff's Department dispatcher.

Oil company

Traveling on side streets instead of Main Street, which would have been more direct, Simmons went to an oil company office at 2601 West Main Street,[68][69] intending to kill owner Russell "Rusty" Taylor, a former employer. He shot and wounded Taylor in the right arm and left side of his chest and killed James David Chaffin, a firefighter and delivery driver for Taylor, with one shot to the head at point-blank range.[67] Chaffin was a stranger to Simmons.[70] He had just returned from a car fire[71] when he encountered Simmons.[68] After the shooting, Simmons fired at a clerk who escaped by ducking behind boxes, initially thinking she had been shot.[72][67] When officers arrived, she gave a detailed description of Simmons and his vehicle.[68][48] The second shooting was reported at 10:27 a.m.[73]

At Simmons' first trial, Taylor said Simmons was working at the Sinclair Mini Mart when Taylor sold the business in October 1986.[67]

Convenience store

Simmons then drove back 3.1 miles through downtown to the Sinclair Mini Mart at 2400 East Main Street. Store owner David Salyer was shot once in the forehead and employee Roberta Woolery was shot once in the jaw.[67][74][75][54] At trial, Woolery said she recognized Simmons as soon as he turned and faced her before he shot.[76] This shooting was reported at 10:39 a.m.[73]

Salyer later testified, "When he squeezed the very first shot, he was grinning." A customer Salyer had been chatting with ran behind some showcases after the first shot and said he was "picking up six-packs of soda and throwing them at him (Simmons), and hollering and cussing and everything else." [67]

Freight company

His final target was the office of the Woodline Motor Freight Company on Bernard Way,[77] where he shot his former supervisor, Joyce Butts, in the head and chest. She later testified that she had no memory of the shooting and that, as his supervisor, they had once argued over Simmons's pay. She would also testify that she had to undergo open-heart surgery to remove a bullet and that she had been left partially paralyzed on her left side.[76][78][79] He then ordered one of the employees, Vicky Jackson, at gunpoint to call the police, telling her “I’ve come to do what I wanted to do. It’s all over now. I’ve gotten everybody who wanted to hurt me.”[80][48] Police received the call at 10:48 a.m.[81]

Surrender and Arrest

When the police arrived, Russellville Police Chief Herb Johnston entered the building unarmed and alone.[82] Simmons handed over his gun, an H&R Model 929 .22-caliber revolver, and surrendered without any resistance. The Ruger was in a paper bag placed on a desk.[65] Ballistics tests would show that the pistol Simmons handed to Johnston was the same weapon used to kill five relatives.[83]

Johnston later recalled, "When I was walking him to the car I asked him 'Why didn't you kill yourself?' He said he was afraid he would make a mess of it. He didn't want to be a vegetable.[84]

After his first trial, his attorney, John Harris, substantiated Simmons' intent, saying his client never intended to survive, that he intended to take his life after the Russellville shootings, but didn't "because of the trouble he was having killing people....He shot seven people—only two of them died."[85] Harris also said Simmons expected to be killed at the first scene, the law firm, by police or a firm employee. While he did receive an Air Force Ribbon for small arms marksmanship, Simmons had told Harris that he was not a hunter and not familiar with guns.[86]

Throughout the 45-minute-long rampage, "wielding" two revolvers, Simmons had killed 2, and wounded four others and briefly held a woman hostage.[87]

Charges and investigation

On December 29, 1987, Sheriff Bolin told a reporter, "He's done nothing in his cell other than lay in his bunk with his face to the wall, just laying there." Circuit Court Judge John G. Patterson held a probable cause hearing for Simmons, who wouldn't answer any questions. He wouldn't even nod or shake his head. Frustrated, Patterson ordered Simmons held without bond and appointed two local lawyers, John Harris and Robert E. "Doc" Irwin as his defense attorneys [31][88] after Russellville Police Chief Herb Johnston filed information accusing Simmons of two counts of capital murder and four of attempted capital murder.[89] Prosecutor John Bynum Filed two counts of capital murder and four counts of attempted murder on December 30 for the victims shot in Russellville. He said he would seek to have Simmons executed if he was found guilty on the capital charges.[90] He also said he would eventually file charges against Simmons in the deaths of his fourteen family members.[91]

On December 30, the FBI joined the sheriff's office and the Arkansas State Police in the investigation because of their expertise in tracking out-of-state witnesses and conducting background checks. Simmons' safe deposit box at Peoples Bank & Trust was ordered sealed. A bank attorney had informed authorities bank records indicated Simmons opened the box "several times during the Christmas holidays.[92]

Simmons was charged with two counts of capital murder in the deaths of 14 family members on January 15, 1988. One count was for the seven family members killed before Christmas. The other count was for those killed on December 26, 1987. The charges were filed after Prosecuting Attorney John Bynym received completed ballistic results from the state crime lab. The results showed that five of the family members had been shot by the .22-caliber pistol that Simmons surrendered when he was arrested on December 28. Bynum said two separate charges were filed because the family slayings were "two separate episodes."[93]

Despite outstanding warrants in New Mexico on charges of incest, Simmons had passed a background check in early 1982 when he was hired as a military personnel clerk at the 5th Army's Little Rock Battalion recruiting office.[37]

Discoveries at the home

"There's nobody here, no sign of life." Sheriff's deputy James Hardy reported from outside the Simmons home on Broomfield Road around 1 P.M. on December 28, 1987.

After he was taken into custody, Simmons refused to talk or respond to any questions about his family. Sheriff James Bolin knew from witnesses in Russellville that Simmons had a large family. With the judge handling search warrants out of town, the sheriff decided an emergency search was justified.[88] Bolin later testified that one reason for entering the home was because tears formed in Simmons' eyes and his lips quivered when he asked about his family.[94]

After the shootings in Russellville, authorities went to the Simmons home on Broomfield Road, about 16 miles north of Russellville. The house's only outside door, a sliding glass door, was barred from the inside with a broom handle inserted in the lower track. They entered the residence shortly before 3 p.m.,[95][96] after Sheriff Bolin, without a warrant,[97] gained access through an unlocked window on the south side of the residence.[9][98][84] A deputy, Ray Caldwell, later said the entry was made to determine if "anybody was alive."[88]

The bodies of William and Renata Simmons and Sheila, Dennis, and Sylvia McNulty were found inside. They had apparently been killed immediately upon arrival, as they were still wearing coats when found.[99]

One of the investigators followed Caldwell with a video camera borrowed from the Arkansas State Police as he entered every room. R. Gene Simmons' room was the last to be entered. It was locked until Sheriff Bolin kicked it in. The only room with an air conditioner, it had shelves lined with books, and behind a curtain, imported beer and gourmet food were stored—luxuries he hoarded.[88]

Sheriff Bolin commented later that electricity to the house had been turned off and that victims might have been dead for several days since unopened presents were found under the tree.[81] Other gifts, also unopened, were found in closets.[95]

Just before sunset, the bodies in the house were taken out in body bags and loaded into vans.[88]

After that discovery, authorities planned to search a large pond for other family members thought to be missing.[100] Pope County Sheriff Jim Bolin said that Simmons' wife, four of their children, aged 7 to 17, and four grandchildren were unaccounted for.[101] On December 29, seven bodies were discovered in a mass grave about 150 feet from the house. When a deputy noticed the freshly dug earth, the search in the pond was stopped and the crew started digging. The burial pit was 3 feet, 4 inches wide and 6 feet, 2 inches long. The first of the seven bodies was located two feet below the surface.[88]

Other searchers then discovered the bodies of the children in the two cars.[102][31] Of the 14 bodies, six were shot and eight were strangled "with cord."[103][104] Testimony and video in the trial identified the cords used were fish stringers.[105][42][88]

Sheriff Bolin said walls and the ceiling in the house had been punched-in in places by what looked like blows from a heavy metal tool, suck as a wrecking bar.[51] Attorney John Harris recalled Simmons telling him he used a hammer.[59]

Autopsy results and other evidence

On December 31, 1987, Sheriff Jim Bolin announced autopsy results for 14 bodies found at the Simmons residence. Eight were strangled,[106] and six were shot. Becky Simmons, 46, was shot twice in the head; Gene Jr., 26, four times in the head and once in the abdomen; Sheila, 24, six times in the head; Dennis McNulty, 23, once in the head; William H. Simmons II twice in the head; Renata five times in the head and twice in the neck. Bolin noted some bodies had cords around their necks.[107]

On January 5, 1988, Prosecutor John Bynam stated that the gun used to kill Kathy Kendrick and J.D. Chaffin in Russellville was also used to kill Sheila, Simmons' daughter. Ballistics tests confirmed that bullets found in their bodies were fired from the same .22-caliber pistol.[108] In May 1988, ballistic expert Paul McDonald testified that the bullets from the Sinclair Mini Market matched those fired from the nine-shot revolver surrendered by Simmons, used in the killings of Kendrick and Chaffin.[109]

During the trial for the family's deaths, Dr. Bennett Preston, the former assistant state medical examiner, testified that all adult victims had been fatally shot,[110] while all minor victims had been strangled using a type of rope.[111]

Victims

The autopsy results showed that the victims died from gunshots or strangulation.[42][103][104][110]

| Date | Name | Age | Relationship | Cause of death |

| December 22, 1987 | ||||

| Ronald Gene Simmons Jr. | 26 | Son | Gunshot | |

| Bersabe Rebecca Simmons | 46 | Wife | Gunshot | |

| Barbara Sue Simmons | 3 | Granddaughter (daughter of Ronald Gene Simmons Jr.)[112][113] | Strangulation | |

| Loretta Simmons | 17 | Daughter | Strangulation | |

| Eddy Simmons | 14 | Son | Strangulation | |

| Marianne Simmons | 11 | Daughter | Strangulation | |

| Rebecca "Becky" Simmons | 8 | Daughter | Strangulation | |

| December 26, 1987 | ||||

| William "Billy" Simmons II | 22 | Son | Gunshot | |

| Renata[114] Lynne May Simmons | 21 | Daughter-in-Law | Gunshot | |

| William H. "Trae" Simmons III | 1 | Grandson | Drowning | |

| Sheila Simmons McNulty | 24 | Daughter | Gunshot | |

| Dennis McNulty | 33 | Son-in-Law | Gunshot | |

| Sylvia Gail McNulty | 6 | Granddaughter/Daughter | Strangulation | |

| Michael McNulty | 1 | Grandson | Strangulation | |

| December 28, 1987 | ||||

| Kathleen "Kathy" Kendrick | 24 | Acquaintance | Gunshot | |

| James David "Jim" Chaffin | 33 | Stranger | Gunshot | |

Motives

Despite the scale and brutality of his crimes, no definitive official analysis of Simmons' motives was ever developed. There were various reasons for this, including:

- Simmons’ Refusal to Cooperate or Appeal: He provided no clear explanation or confession, remaining largely silent about his reasons. After both trials, Simmons explicitly waived his right to appeal.

- Swift justice: Given the strong evidence and Simmons' refusal to appeal, there was little need to concentrate on why he did it. The rapid timeline—less than three years from crime to execution, with convictions in two separate trials—left little room for prolonged inquiry.[115]

- Limited Psychological Evaluation: While Simmons underwent a competency evaluation to determine his ability to stand trial, this assessment focused narrowly on his sanity and capacity to understand the proceedings—not on a comprehensive analysis of his motives.

- Complexity and Ambiguity of Motives: The evidence from the crime scenes, witness statements, and limited documentation suggests a tangle of potential motives, none of which were conclusively explored due to Simmons’ silence and the lack of follow-up investigation.

- Legal and Social Context: The legal system in Arkansas at the time prioritized swift justice over exhaustive motive analysis, especially given Simmons’ willingness to accept his fate.

- Lack of Collateral Evidence: Unlike many high-profile killers, Simmons left no manifesto, diary, or correspondence explaining his motives. Family members who might have provided insight were either dead or unable to offer more than speculation, hampering official efforts to establish a motive

Simmons' abusive control and the threat of the family's growing resistance

In New Mexico, Simmons exerted complete control over his family, subjecting them to relentless abuse—primarily verbal, but at times physical. He first struck his wife in front of their children in 1978. After school and on weekends, the kids mainly went around and found rocks—they were building a stone wall around the property.[15] The eldest daughter, Sheila, endured the worst of it, suffering sexual abuse at his hands.

According to attorney John Harris, when the family fled New Mexico, Simmons became a fugitive with a felony warrant hanging over him. Unbeknownst to him, New Mexico had ceased pursuing that warrant, and the case became inactive in 1982. Simmons remained convinced that there was still an active warrant out for his arrest. As a result, his grip on the family tightened, and the abuse escalated. Financial struggles and personal failures deepened his obsessions, pushing him further into isolation and tightening his oppressive control over those trapped under his rule.[116]

Simmons confided to Harris that he was concerned that his wife might divorce him and that would be the end of everything with his record (the incest charges). He had a lot of debt and had quit his remaining part-time job. Becky had a lump in her breast that compounded his worries.[59]

Simmons kept a tight rein on his family, according to schoolmates, particularly his wife and 17-year-old daughter. While the children were all talented in school, they were intensely shy and reluctant to discuss family life.[117]

According to family acquaintance Janet Mayhew, the children had a strained relationship with their father and preferred his absence. “They didn’t like him at all,” she said. The children reportedly had hideouts on the Simmons property to avoid him when he was home. Jennifer Mayhew noted they favored the periods when he worked two jobs, with their mother remarking they’d be content if he worked “seven days a week, 24 hours a day.”[99]

Becky Simmons stayed with her husband out of fear, according to her sister, Edith Nisby, on December 30, 1987. "I think she was afraid to leave," said Mrs. Nesby. "She was a woman with small children and no work skills. She was too ashamed to turn to her family after the sexual abuse thing. She was just afraid and she didn't know what to do."[57]

During the investigation, local residents expressed shock over the discovery. Edna Baker, a longtime resident, described it as "the worst thing since the Civil War" to happen in Pleasant Grove. Neighbors recalled seeing Simmons supervising his children as they gathered mud and stones to fill ruts in their driveway—a memory that resurfaced for some, including Ron Standridge, upon learning of the tragedy.[99]

In a 1987 press briefing on December 31, Pope County sheriff's investigators suggested that Ronald Gene Simmons Sr., may have been driven to rage by his wife Becky's secret plans to leave and divorce him due to his abusive behavior.[107][118][43] In Russellville, witnesses told them Simmons harbored personal grudges against victims shot in Russellville and that he had an unrequited amorous infatuation with Kathy Kendrict who had rejected repeated advances and filed a sexual harassment complaint against Simmons.[31]

The three oldest siblings, all adults who had left home, were working in concert to convince Becky to leave Simmons.[42]

In a summer 1987 four-page handwritten letter from Becky Simmons to son William, she wrote, in part, "I am a prisoner here and the kids too ... Dad has had me like a prisoner ...." "I don't want to live the rest of my life with Dad." "Every time I think of freedom I want out as soon as possible." The slain wife of R. Gene Simmons was contemplating leaving, but worried she could not find a job but decided to wait. "God is telling me to be more patient, Right now I'll just say (I'll) do some checking and then it will help me make my decision." "I know when I get out I might need help, Dad has had me like a prisoner, that the freedom might be hard for me to take, yet I know it would be great, having my children visit me anytime, having a telephone, going shopping if I want, going to church." The letter depicts a suppressed, isolated family living in fear.[119][120][121]

In the letter, Becky Simmons wrote she wanted Loretta to move in with William and Renata after the teen turned 18. "She wants to go to college and she can get a job, too.[122]

A friend of 17-year-old Loretta said that Loretta told her that her mother had been thinking about leaving with the children because of Simmons' repressive and abusive behavior, that the only thing stopping her was that she was afraid she wouldn't be able to support the children, and, most recently, Mrs. Simmons had talked about going to San Antonio, where Loretta's brother, Gene Jr, was living.[45]

In a September 29, 1987, letter to Sheila, Becky wrote,

Billy, I know, worries over me so I've been doing a lot of thinking of leaving your dad. I've been a prisoner long enough. Bill and I are trying to find a way. I just don't want to give your dad anything. He has mistreated us all long enough, so I feel no pity for him, and being alone is what he deserves. All this will take time but I don't want to continue this life with Fatso.

Becky often referred to Gene as "Fatso" in letters that didn't get mailed through him.[42][9]

In another letter, Becky said she was a prisoner and yearned for freedom.[123]

Becky Simmons' family said they didn't trust Simmons because he seemed to get stranger and stranger each year. Becky's older sister, Viola O'Shields, said, "He was a very loving man at one time. He loved his family."[15] Manual Ulibarri, her brother, said Simmons had his sister "so isolated so she couldn't go anywhere or do anything. The only time she could go out was to wash clothes."[19] "Gene never liked his stepfather," said his sister-in-law, Edith Nesby. "Actually, he didn't like anybody. ... Anything that went wrong was always somebody else's fault."

"In my heart, I think I know the reason why. Like told you before, he just had lost control of the family. He couldn't bear to be with... Like a general, he had to have control all the time, said Manuel. "After the incest he lost control. My sister Becky was sleeping in the room with the girls.... Gene just lost control of the family and couldn't take it. In other words, they just didn't have anything to do with him and he couldn't take it.[60] Ulibarri said that another factor that prompted the family massacre was Simmons' belief his family was planning to leave him. "Gene thought he (Ronald Gene Simmons Jr.) was coming to pick up the family and take them with him back to San Antonio."[14]

News Anchor and a Local Reporter

Simmons initiated communication with KHTV news anchor Anne Jansen through a letter, leading to an exchange that consisted of eight letters from Simmons and four two—to three-hour conversations. These interactions occurred across multiple locations: twice at the Pope County Detention Center, once at Tucker Unit, and once at Cummins Unit. Simmons requested that Jansen keep their discussions confidential, emphasizing that he would have ceased communication if he believed they were intended for journalistic use.

In their initial conversation, Jansen noted Simmons' pronounced paranoia. He expressed suspicion that even unsecured objects, such as light bulbs and wall switches, might conceal listening devices. He remained highly vigilant, consistently monitoring his surroundings.[88][124]

Simmons also communicated with another reporter, Russellville Courier Democrat reporter Laura Shull, including once in his Pope County jail cell.[125]

Surrender versus suicide

It was thought that Simmons planned to kill himself after his rampage in Russellville. After several shots from the .22-caliber pistols failed to kill multiple victims, he worried that using it for suicide might leave him disabled instead. He also doubted his chances of dying if he tried to shoot it out with the police.[59]

Trials, convictions and appeals

Summarize

Perspective

On December 30, 1987, Simmons was transferred from the Pope County Detention Center to the Arkansas State Hospital in Little Rock[126] after Circuit Judge John Patterson ordered him held without bond and to undergo a psychiatric evaluation. Despite a backlog of admissions, Simmons was immediately admitted on an emergency basis at Rogers Hall, which housed the criminally insane, arriving there under heavy security because of threats on his life.[127] Dr. Roy Ragdale said hospital policies allowed patients to be admitted early if they were charged with a capital crime.[123]

Following 60 days of psychological testing, on February 29, 1988, State Hospital director Dr. Roy Radsdale said that Simmons was competent to stand trial and was responsible for his actions at the time of the killings. Ragsdale said that Simmons was diagnosed as having a mixed personality disorder “with narcissistic and paranoid features,” Ragsdill said. “It is a clinical way of describing coping techniques in dealing with his feelings and stress.”[128]

Simmons was returned to Pope County, where Judge Patterson accepted the state hospital's finding that he was competent to stand trial and that he was not insane at the time of the slayings.[4][129] Patterson also set a May 9 trial date.[130]

Patterson said on March 7 that he would be "hard-pressed" to label Simmons an indigent since he was receiving a military pension of about $917 a month. He ruled that Simmons could pay for his defense, for which Simmons' attorneys had accumulated about $11,000 in fees and expenses. Prosecutor Bynum objected to the defense's request for payment, saying it would deplete the county's indigent defense fund, which only held $15,278 in February. Everything of value that Simmons had eventually went to his attorneys, including concrete blocks from the wall that had shielded the house from view from Broomfield Road and gifts from Christmas that had never been opened.[131][132]

Trial for Russellville shootings

In his first trial, Simmons was charged with murdering Kendrick and Chaffin, attempting to murder five others, and kidnapping a sixth on December 28, 1987.[133]

In a plea arraignment on March 24, 1989, Simmons spoke for the first time in court since his arrest and pleaded innocent to four capital murder charges, five counts of attempted capital murder, and one count of kidnapping and saying, "In the interest of justice... I request a speedy trial.[134] In the same hearing, acting on a request by Simmons attorneys, Judge Patterson ruled that the trial for the Russellville spree would take place in Franklin County.[135]

Simmons wanted the death penalty from the very beginning. A death sentence, under Arkansas law, was only permitted upon a jury's recommendation. If he had pled guilty, the only available sentence would have been life imprisonment without the possibility of parole.[85][59]

Defended by two local court-appointed attorneys,[136] John Harris and Robert "Doc" Irwin,[59][137] Simmons' first trial began on May 9, 1988, in Ozark—moved there because of widespread news coverage.[138] A seven-man, five-woman, all white, with two alternates, was selected on Monday, May 9 from a jury pool of 113 people.[139] The jury was overwhelmingly older, working-class, with limited formal education.[140]

On Tuesday afternoon, Judge Patterson excused a juror following an hourlong meeting with attorneys. He had been told the juror made a derogatory remark about Simmons but declined to declare a mistrial, citing the availability of two alternates. Seventeen prosecution witnesses testified on Tuesday. Thirteen witnesses testified on Wednesday. Nine of the thirty prosecution witnesses identified Simmons as the man involved in the rampage. One witness said Simmons had told him he would "like to get even" with some people in the area and that there were a few people in town he would like to get even with[67][76]

In the four-day trial, Simmons was linked to shootings at four businesses through eyewitness accounts and ballistics evidence.[141][142]

The defense rested without presenting evidence or calling any witnesses even though they had subpoenaed eleven.[94] They had previously decided against an insanity defense.[137] "Doc" Irwin had said he planned to call about five witnesses but told the Gazette he was unable to find one. “We didn’t have any witnesses,” he admitted after the verdicts were reached. “We looked high and low.” [143]

Prosecutor John Bynum, arguing for death, said, "There is nothing in the record that says this man is entitled to a break—nothing.[144]

The jury deliberated less than 1½ hours before convicting Simmons on May 12, 1988. After hearing arguments on whether to sentence him to life in prison or death, they deliberated another 2 hours[145] and returned with a sentence of death.[48][146][147] Simmons was also sentenced for 30 years for each of four attempted capital murder counts, 20 years for a fifth attempted capital court, and 7 years for a first-degree false imprisonment charge.[148][149]

After jurors had been excused, Simmons told Circuit Judge John Patterson he had a statement to make. Speaking softly from the witness stand, Simmons stated in open court that, after careful thought and consideration, he was ready to waive all his rights to appeal.[141][150]

Later that evening, one juror said, "It's something the jury was not proud of." Another said the jury had no problem with its decision.[151]

My statement is that if the jury renders the most proper and just and wise sentence of death in this case, I, Ronald Gene Simmons Sr., want it to be known that it is my wish and my desire that absolutely no action by anybody be taken to appeal or in any way change this sentence. It is further respectfully requested that this sentence be carried out expeditiously. I want no action that will delay, deny, deter or denounce this very correct and proper death sentence. My attorneys have repeatedly counseled me to appeal. However, that is not what I want. I believe now and always have in the death penalty. To those who oppose the death penalty, I say, in my particular case, anything short of death would be cruel and unusual punishment. I am of sound mind and body and have been seen by psychoanalysts who can verify that I am capable of making a clear and rational decision. I have given clear and careful thought and consideration so there is nothing that will cause me to change my mind. Let the torture and suffering in me end. Please allow me the right to be at peace.

After Simmons read his statement, Dr. Lew Neal, a psychiatrist, testified that Simmons was mentally competent to make the request. "There is no way he is going to change his feelings on this," Dr. Neal said. Simmons' attorneys said Simmons wrote the statement days earlier against their advice.[154]

Later that evening, James Lee, a spokesman for the attorney general's office, said that Simmons had the right to waive his appeals. "Under Arkansas law, the appeal is not automatic, it is not mandatory."[155]

Post-trial interview and hearings

Simmons said, "Death is not to be feared." in a May 15 two-hour interview with a reporter from the Russellville Courier-Democrat. "It is what comes before death" that is to be feared. "I have no doubts that this (death sentence) is right, but I won't believe it until it happens." Refusing to answer anything about what happened at his home, he criticized the criminal justice system, saying those who need punishment don't get it. Describing himself as an introvert, he said he didn't answer all questions when he was examined at the State Hospital.[156]

On May 16, Judge Patterson found Simmons to be of sound mind and could waive his right to appeal. Patterson issued an order for Simmons to be executed by lethal injection at 11 a.m. June 27.[157] Calling his sentence "proper punishment for the crime," Simmons told the judge he would not try to stop the execution. "I arrived at my decision in regard to the proper punishment on Dec. 28 and don't hold your breath for me to change it.[158] Simmons told Patterson he had decided to seek execution on the day of the shooting spree.[159]

Judge Patterson reminded Simmons that "any time prior to execution, you have the right to change your mind and appeal." Simmons told the court that his decision was made the day of the shootings in Russellville and that he wouldn't change his mind.[160]

Simmons property sold at auction

In early January 1988, Dorothy Gueller of Woodhaven, N.Y., filed a foreclosure suit against Simmons seeking return of the property she sold Simmons on Broomfield Road and $28,081 she said was still owed.[161] The foreclosure petition was approved in May after there had been no payments since November 1987. On June 15, the property was sold at auction on the steps of the Pope County Courthouse. The only bid came from the woman Simmons had bought the property from.[40] On March 29, 1989, the house, which had been subjected to ongoing vandalism, was destroyed by fire. The state fire marshal ruled the blaze as arson.[162][163] The site has faded from public attention with no subsequent property development.

After the trial in Ozark

Simmons met several times with Roger and Viola O'Shields. Viola was Becky's sister. Simmons told Roger that he had intended to kill himself after he was finished with his victims. When Roger asked him why he changed his mind, Simmons told him, “Do you know what kind of ammunition I was using? .22 caliber hollow points. They don’t penetrate. They splatter. I did not want to shoot myself and become a vegetable.”[133]

On June 16, 1988, just over a week before his scheduled execution, the Arkansas Churches for Life filed a petition with the Arkansas Supreme Court, seeking a stay of execution and asserting that death sentences should be appealed.[133]

In a 6-1 ruling, the Arkansas Supreme Court issued a temporary stay of the execution on June 20 after attorney Mark S. Cambiano for Catholic priest Louis J. Franz raised issues of whether Arkansas had or should have had a mandatory review of capital cases or the waiver of appeals in such cases.[164]

After the state Supreme Court action, On June 21, Circuit Judge Patterson said that the trial for the murders of Simmons family members, initially scheduled for July 18, would be postponed indefinitely pending decisions by the higher court.[165][166]

The Arkansas Supreme Court terminated the temporary stay on July 1, 1988, in a 5-2 ruling,[167] holding that Rev. Franz did not have standing in the case and that Simmons understood his choice not to appeal. They also held that automatic appeals were not mandated but that the court would not automatically acquiesce to a defendant's desire to decline his right to appeal.[168]

With the stay lifted on July 15, on July 15, Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton set Simmons's execution date for August 9 in a letter to A.L. "Art" Lockhart, director of the Arkansas Department of Corrections.[169]

U.S. District Judge G. Thomas Eisele stayed the execution on August 3, 1988, telling lawyers he would decide later in the month whether a court review in death penalty cases is mandatory but wouldn't consider if others had standing to intervene nor whether Simmons was competent to waive his right to appeal.[170] Eisele's stay came after attorney Mark Cambiano filed motions on August 2 on behalf of Catholic priest Louis J. Franz and Darrel Wayne Hill, an inmate who was also on death row.[171]

Attorney Mark Cambiano filed a motion on August 12 asking that a temporary guardian be appointed to Simmons, claiming that Simmons' attorneys, John Harris and Robert W. "Doc" Irwin, had provided ineffective assistance of counsel.[172]

After Circuit Judge John S. Patterson scheduled a tentative trial date for the first week of December, defense attorneys requested Simmons be brought to Russellville to make him more accessible for preparation of motions pending in state and federal courts. Simmons was moved from death row to the Russellville jail on August 19[173] and returned to death row at the Maximum Security Unit near Tucker on September 1.[174]

Judge Eisele ruled on September 23 that Rev. Franz and inmate Hill did not have standing to appeal Simmons' execution and that Simmons himself must make any further appeals in the case. He also ruled that the Arkansas Supreme Court had established that mandatory capital case appeals were not required.[175]

On September 29, Judge Eisele ordered more psychiatric evaluations for Simmons and appointed Little Rock lawyer John Wesley Hall Jr., to advise him on possible avenues of appeal. Before making a final ruling on the competency issue, Eisele wanted a 30-day assessment of Simmons by authorities at the Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield, Missouri.[176] Hall thoroughly reviewed the case records and decided that Simmons' attorneys had made all of the appropriate arguments and objections and that the appeal issues had been addressed.[59]

A December 29 order provided to the Arkansas attorney general's office by Judge Eisle ruled that Simmons could waive his right to appeal his conviction.[177]

Trial for family killings

On December 21, 1988, Judge John Patterson issued an order moving Simmons' trial for the murders of his 14 family members to Clarksville, in Johnson County because of pre-trial publicity.[178] The 14 deaths had been consolidated into one count of capital murder.[179]

On January 18, 1989, in an evidentiary hearing, Judge Patterson refused to bar most of the evidence the state gained when officers entered Simmons' home. Sheriff Jim Bolen and other officers entered the home on December 27, 1987, after Simmons had been arrested in Russellville following the shootings there. They testified that their concern was for the welfare of the family. They entered under guidelines that allow officers to take action when they have reason to believe an emergency exists.[180] Bolin said he thought they could be injured, perhaps bleeding to death in the house and that his fear was based on Simmons' reaction when asked about his family, though he wouldn't answer any questions.[181] He also said that, when asked if he would consent to a search of the residence, Simmons "shook his head, no, his lips was quivering, and his eyes watered up."[94]

Sheriff Bolin testified, "I felt very deeply that his family might be in there, might be shot, and needing medical help. We couldn't find them. He wouldn't tell us where they were." He also said, "The first thing we did when we got in there was to check each body to see whether there was any life left in them."[182]

Patterson ruled that the 14 deaths would be treated as one count of capital murder.[183]

The trial began on Monday, February 6, with jury selection from a pool of 89 potential jurors. Judge Patterson addressed the publicity issue by asking, "Is there anybody who has not heard anything about this case?" Nobody raised their hands.[184]

Extra security had been brought to the courthouse, including state troopers inside the building and the courtroom.[133]

Jury selection was completed late Tuesday, with four women and eight men seated. The last two jurors were selected after the defense exhausted its peremptory challenges.[185]

During opening arguments on Wednesday, in a Clarksville courtroom crowded about 100 spectators, prosecutor John Bynum said the prosecution would present a note by Simmons that authorities found in a safe deposit box at Peoples Bank in Russellville.[186][187] "It will show you and indicate to you a motive as to why Mr. Simmons killed some these people," Bynum said, and that it would describe a love-hate relationship with his oldest daughter with whom he had fathered a child. A dozen relatives of the victims sat on two benches at the front of the courtroom.[83]

On February 9, in testimony, Dr. Bennett G. Preston, former assistant medical examiner for Arkansas, summarized what he found when he did autopsies on the 14 bodies. Other testimony indicated that no firearms were found at the Simmons home.[188]

As to motive in the trial, a family friend told investigators that Simmons' wife had been saving up money to divorce Simmons when the killings happened.

On the morning of February 10, a state firearms and tool marks examiner testified that bullets taken from the bodies of five of the victims matched a gun Simmons had with him when he was arrested.[187] Bullet fragments from the sixth victim could not be positively identified.[189]

During a routine sidebar conference just before noon between the judge and both parties, Simmons lunged between the lawyers and slugged John Bynum, the prosecutor, in the chin, "sending spectators shrieking and ducking beneath their seats"[190] After missing with a second punch and reaching for the holstered gun of one of the baliffs,[191] Simmons was subdued by court officers[192] who swarmed over him and whisked him out a side door.[133][193] Jurors watched wide-eyed and some relatives of the slain family dove for the floor. Charlotte Crosston, whose daughter and son-in-law died in the murder spree, said, I'm glad he showed the jury, and I'm glad the jury got to see what he's really like.[194]

Bynum had introduced a letter between Simmons and his daughter Sheila in which Simmons expressed anger that Sheila had revealed that he was the father of her child, and that he would see her in Hell.[1][195] Bynum later said he saw the punch coming right before it landed. "I was startled, but it didn't hurt me. He may have tried to hit me on the chest, but the only blow I felt was the one to the face.

Judge Patterson immediately had the startled jurors removed from the courtroom and before declared a recess, telling them, "I want you to set aside what in the courtroom for now. The trial has gone on for five days. We want to finish if we can. You need to disregard the incident that just happened here today.[190]

Simmons was later asked by his attorney why he had sucker punched the prosecutor. Simmons replied, “I am in control, I am in control.” Harris thought it was intended to sabotage any defense that might be offered.[59] Simmons sought no sympathy from the jury and aimed for a death sentence, even striking the prosecutor to ensure it.[133]

Sometime later, in one of their confidential, off-the-record meetings, Ann Jansen spoke with Simmons about hitting the prosecutor. She asked, "Gene, what did you do?" He smirked and replied, "MNM," explaining it stood for "mitigating or mitigation neutralizing maneuver." He wanted the jury's last impression to be an act of violence to secure a death penalty.[133]

After the recess, Lt. Jay Winters of the Pope County Sheriff's Department read the letter introduced by Bynum, which was to Simmons's eldest daughter, Sheila McNulty. "I told you that your lack of communication with me was going to be your downfall." Simmons wrote. "You have destroyed me, and in time you will destroy yourself." "If you are trying to hurt me, then you should be very proud of yourself, because you have done a very good job of it. You have destroyed me. I do not want D. to set foot on my property. He turned you against me. You want me out of your life. I will be out of your life. I will see you in hell."[193]

The trial included just 18 prosecution witnesses, and the defense didn't present a case,.[196] However, before Simmons' attack on Bynum, they had planned to call Vicky Jackson—the Woodline Freight employee Simmons told to call police—, a police dispatcher, and a ballistics expert.[197]

Handcuffed after the earlier outburst, Simmons showed no emotion when he was found guilty that evening at 8:30 PM after the jurors deliberated for more than four hours. The jury returned with a sentence by lethal injection at 11:08 PM. Relatives of the victims clapped when the verdict was announced, but the courtroom was silent when the sentence was read.[187]

On February 11, after Simmons told Judge Patterson he knew of no reason he should not be immediately sentenced, the judge set the execution for March 16.[192][198][133]

He refused to appeal his death sentence, stating, "To those who oppose the death penalty – in my particular case, anything short of death would be cruel and unusual punishment." The trial court conducted a hearing concerning Simmons' competence to waive further proceedings, and concluded that his decision was knowing and intelligent.

After the trials

Judge John Patterson allowed Simmons to waive his appeal of the death sentence in a March 1, 1989, hearing. After the hearing, Simmons talked to reporters in a rare move. While he declined to discuss the crimes or his apparent death wish, he made threatening and disparaging statements about people who had blocked his first death sentence, Rev. Louis J. Franz of Star City and Morrilton attorney Mark Cambiano. “Perhaps you folks can suggest to Scum-Cambiano and Joker Franz that as they crawl through their self-created cesspool, that maybe they ought to keep an eye over their shoulder,” Simmons said. “Someone might just want to put their lights out.”[199]

On March 10, the state Supreme Court ruled Simmons competent to waive his appeal for his February conviction. On March 13, the court rejected a petition for review from another death row inmate, Jonas Whitmore. The following day, the petition was filed with US Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun, who referred it to the entire court. On March 15, 1989, the U.S. Supreme Court delayed the execution scheduled for the next day,[200][201]

On March 29, 1989, the 8th Circuit again delayed Simmons' execution, set for April 5 by Governor Clinton, to review Eisele's ruling in the first trial and allow the U.S. Supreme Court to weigh Whitmore's petition on the family slayings, the second trial.[201]

On July 3, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to review Whitmore's appeal, with arguments to be heard in October.[202]

The situation was bizarre as Ronald Gene Simmons and Attorney General Steve Clark both wanted the trial to end. Simmons submitted a sworn statement saying, “Do not appeal for me or try to help me; I willingly accept my punishment.”

After a 13-month pause due to Whitmore's appeal, on April 24, 1990, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Whitmore v. Arkansas that Whitmore had no standing to intervene, leaving the denial of an appeal for a death sentence unaddressed.[203] The net effect of the ruling was that the only person that could stop the execution was Simmons.[204]

On May 31, Governor Bill Clinton signed a new death warrant for Simmons for June 25, 1990, nearly two years after the original date. There would be no more obstacles—Simmons was set to die, leaving many wondering if this would bring the relief they sought.[133]

Execution

Summarize

Perspective

Simmons was kept alone on death row. Other prisoners were upset because he didn't fight his death sentence, and they thought it hurt their cases.

In June, Assistant Attorney General Jack Gillean said Simmons could stop the execution at any time up to the point of the lethal injection by saying he wanted to pursue his right to an appeal. "That is because he is a volunteer, which is the word we're using for people who aren't appealing and who want to be executed."[165][59]

On May 31, 1990, Arkansas governor (later President) Bill Clinton signed Simmons' execution warrant.

Before his execution on June 25, Simmons gave a brief, confusing final statement, "Justice delayed finally be done is justifiable homicide."[205] One of his attorney, John Harris, said he thought Simmons accepted his punishment but felt that it had been delayed for too long.[206]

Fourteen people were present in a darkened witness room. Two witnesses were reporters—Bob Simmons (Associated Press bureau chief) and Scott Bowles (Arkansas Gazette).

At 9 p.m., curtains over the windows of the execution chamber opened without notice. Light from the bare white room brightened the witness room.

Simmons lay strapped in a gurney about eight feet from the first row of witnesses, his head to the witnessess' left, his feet to the right. Two intravenous bottles hung over his head. He looked straight up, into the fluorescent lights of the chamber, blinking frequently. Simmons was covered from chin to toe in a white sheet with his arms bared and strapped to his side. Catheters were in each arm. "He's not a very big man, is he?" (one of the) witnesses whispered to himself. At 9:02 p.m., warden Willis Seargent announced the execution was to begin. Simmons continued to blink and glance about him. His head, held tight by a brow leather strap, was unable to move, but he tried to glance above him at the executioner's room. He then looked once to his right, toward the witnesses. His eyes returned to the ceiling, blinking frequently. At 9:06, Simmons called out, "Oh, oh," and he began to cough. His eyes shut. He seemed to nod off, as if asleep. He continued to cough after his eyes shut. The convulsions raised the sheet around his stomach and caused his gurney to move. Over the next four minutes, Simmons continued to convulse and shake the gurney, although less frequently as the minutes passed. His fingers and face began to turn purple. By 9:10 p.m., Simmons was still. At 9:15, prison medical administrator Byus checked the catheter in Simmons' right arm. At 9:17 p.m., Byos held a stethoscope to Simmons' chest, held Simmons' right wrist, then touched the man's neck. At 9:18 p.m., the Lincoln County coroner entered the chamber and examined Simmons. He pronounced Simmons dead at 9:19 pm.[207]

Simmons died by the method he had chosen, lethal injection, in the Cummins Unit.[208] This execution was significant for Arkansas: it was the first by lethal injection,[209] the first where an inmate waived his right to appeal, and the second execution since the resumption of capital punishment after a 26-year moratorium, occurring just one week after the prior execution.[210]

Two hours prior to his execution, prison officials inquired about Simmons' wishes for the disposition of his remains. He responded, "No comment."[211] With no surviving relatives willing to claim his body and no specific burial instructions provided, Simmons was buried in Lincoln Memorial Lawn cemetery near the Varner Unit in Lincoln County, Arkansas.[48][59][212] Details of the burial arrangements remained undisclosed until 20 minutes before the service. Nancy Madden, Simmon's sister, and members of her family were present at the graveside ceremony.[213]

Motive

Simmons never expressed remorse for his actions.[133]

Simmons repeatedly sought execution to end his suffering but shared little with authorities. Acquaintances suggested his silence reflected a desire to retain control over his family posthumously.[4]

A CBS Evening News report on September 29, 1987, stated that authorities had one major unanswered question, expressed by Sheriff James Bolin, "Why?"

After the execution, that question had never been fully answered, certainly not by Simmons.

Afterward

Three videotapes from the murder scenes at the Simmons property were burned in mid-August 1990 after Judge Patterson authorized their destruction.

"I did what I’ve wanted to do ever since Simmons was executed, destroy the tapes," Sheriff Bolin said. "I’ve had calls from all over the country, even before he was executed, from people wanting the videotapes. The calls have been heavy since the execution."

The tapes document the condition of 14 bodies: four adults and one child found in the house, seven from a shallow grave, and two children wrapped in trash bags in a car trunk. Parts were shown to the jury during Simmons’ trials.[214]

Simmons' two pistols were auctioned for $2,925. One gun, which was not used in the murders, was sold to a resident of Pottsville, who bought it as a souvenir for $1,325. The second weapon, the gun Simmons used to kill eight people, was purchased by John C. Harris, one of Simmons' attorneys. He said he thought bids on his former client's guns were "too low." Most of the crowd of over 100 and about a dozen journalists were there for the spectacle. Only 13 people bid on either gun and virtually all of the bidding was done by just four men.[110]

See also

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.