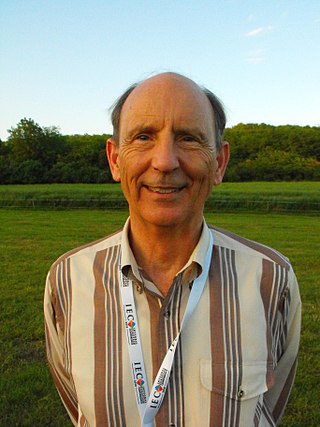

Roger Walsh

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Roger N. Walsh (born 1946) is an Australian professor of Psychiatry, Philosophy and Anthropology at the University of California, Irvine, in the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, within UCI's College of Medicine. Walsh is respected for his views on psychoactive drugs and altered states of consciousness in relation with the religious/spiritual experience,[citation needed] and has been quoted in the media regarding psychology,[1] spirituality,[2] and the medical effects of meditation.[3] A 2011 review article by Walsh titled "Lifestyle and Mental Health", and published in the journal American Psychologist, gained significant attention.

Education

According to his profile, Walsh received his degrees from the University of Queensland and is involved in six ongoing research areas:

- comparison of different schools of psychology and psychotherapy

- studies of Asian psychologies and philosophies

- the effects of meditation

- transpersonal psychology

- the psychology of religion

- the psychology of human survival (exploring the psychological causes and consequences of the current global crises).[4]

Lifestyle and Mental Health (2011)

Summarize

Perspective

| Lifestyle and Mental Health | |

|---|---|

| Created | October 2011 |

| Author(s) | Roger Walsh |

| Media type | Journal article in the American Psychologist |

| Purpose | To argue that mental health professionals have underestimated the importance of lifestyle factors on mental health |

| Official website | |

| Free full text of article hosted by UC Irvine | |

Lifestyle and Mental Health is the title of a 2011 review article published in the journal American Psychologist by Walsh.[5][6] It is used in patient education[7][8] and has garnered attention from editorials,[9][10] books, and the medical literature. The article is cited as "important"[7] and "seminal."[11] It discusses categories of potential lifestyle changes—referred to as therapeutic lifestyle changes (TLCs)—to improve one's mental health along with supporting research.[11] According to Google Scholar, it has been cited over 1050 times as of February 2025.[12]

Summary

The stated thesis of the article is that:

"Health professionals have significantly underestimated the importance of lifestyle for mental health. More specifically, mental health professionals have underestimated the importance of unhealthy lifestyle factors in contributing to multiple psychopathologies, as well as the importance of healthy lifestyles for treating multiple psychopathologies, for fostering psychological and social well-being, and for preserving and optimizing cognitive capacities and neural functions."[13]

— Walsh, in Lifestyle and Mental Health (2011) p. 579

Walsh writes that TLCs can be effective, affordable, and stigma-free. He states they can boost self-esteem, improve physical health, be enjoyable and thus potentially self-reinforcing. Walsh notes even clinicians can benefit from meditation given it can help cultivate "calmness, empathy, and self-actualization."[14] Walsh cites evidence suggesting that the positive effects of TLCs might even generate significant multiplier effects in society by positively impacting "families, friends, and co-workers."[14]

Exercise is presented by Walsh as "a healthful, inexpensive, and insufficiently used treatment for a variety of psychiatric disorders."[15] He states that exercise reduces the risk of depression, age-related cognitive decline, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease according to cross-sectional and prospective studies. He writes that "in terms of therapeutic benefits, responsive disorders include depression, anxiety, eating, addictive, and body dysmorphic disorders. Exercise also reduces chronic pain ... and some symptoms of schizophrenia."[16]

Walsh emphasizes a "rainbow diet" mainly consisting of fruits and vegetables (a multicolored plant-based diet) with some salmon-like fish content, for omega-3s. Walsh endorses calorie restriction given obesity may be associated with reduced cognitive function, reduced gray matter, and reduced white matter. Walsh notes that "fish and fish oil" are fundamental for mental health given that "they supply essential omega-3 fatty acids, especially EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and DHA (docosahexaenoic acid)" for neural functioning.[17]

Walsh writes that time in nature has healing and restorative effects, but modern societies tend to isolate us from sunlight and box us away from nature, which reduces us, through digital immersion, to being people who "have become the tools of their tools."[18] In contrast, Walsh states that time in nature is associated with "greater cognitive, attentional, emotional, spiritual, and subjective well-being."[19]

Walsh emphasizes the importance of relationships, writes that one's social connections are a cornerstone of one's wellness, and states "the health risk of social isolation is comparable to the risks of smoking, high blood pressure, and obesity."[20] He states that the benefits of social connections include "enhanced happiness, quality of life, resilience, [and] cognitive capacity."[19] Walsh says that helping patients improve their interpersonal relationships should be a standard part of mental health care.[21]

Walsh encourages participation in recreational and enjoyable activities such as those that involve play, humor, and the arts, noting that the evidence suggests that "enjoyable recreational activities, and the positive emotions that ensue, foster multiple psychological and physical benefits."[21]

Given that chronic stress is a health threat, Walsh highlights the importance of stress management. Stress relieving modalities include psychotherapy, aforementioned TLCs, and self-management skills. Potential modalities included under the rubric of self-management skills are somatic therapies, including muscle relaxation techniques, self-hypnosis, guided imagery, tai chi, qigong, and yoga. Meditation is presented as particularly beneficial—more effective than psychotherapy.[22]

Walsh emphasizes "religious and spiritual involvement" stating that these practices are pervasive in human societies and are used to deal with stress. Walsh writes that an emphasis on love and forgiveness is considered beneficial, whereas a focus on punishment and guilt might do harm.[23] Walsh cites evidence that "those who attend religious services at least weekly tend to live approximately seven years longer than those who do not."[24] He also discusses developmental differences in religious faith.[25]

Walsh highlights "contribution and service" and states that significant evidence supports the idea that altruistic behavior is associated with "multiple measures of psychological, physical, and social well-being."[26] However, this association is said to begin to break down when the motivations for pro-social behavior are "driven by a sense of internal pressure, duty, and obligation."[26]

Walsh raises concerns over technological changes causing disruptions to the well-being of individuals. Environmental and lifestyle changes are seen as other variables to monitor by the health professions.[27] He discusses the potential challenges to implementing TLCs during psychotherapy sessions and calls upon practitioners to be aware of the Rosenthal effect: "the self-fulfilling power of interpersonal expectations."[28] Walsh asks if an underemphasis on TLCs is a sign of professional deformation in medical practice. Additional TLCs beneficial for mental health that were not discussed include "sleep hygiene ... ethics, community engagement, and [moderation] of television viewing," according to Walsh.[28] He calls for policy changes to support TLCs.

Reception

Editorials

In response to the article, the editors of the Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, Grayson & Meilman, wrote an article entitled "Eat Your Veggies." They stated that Walsh's "indictment of mental health professionals does seem bit unfair, at least as applied to those of us working on campus."[9] They found the recommendations "doctor-like" and "simplistic" and summarized the entire article as follows:

"Exercise is both preventive and therapeutic for mild to moderate depression and increases brain volume in the bargain. (Yet only 10% of mental health professionals recommend it.) Diets emphasizing multicolored fruits and vegetables and some fish may prevent or ameliorate psychopathologies, and fish oils may ward off first episode psychosis. Spending time in nature is good for you. Not so good are artificial environments (bad news for those of us in windowless offices) and media immersion—too much television, e-mail, texting, Internet surfing and the like (bad news for just about all of us)."[9]

Yet, Grayson & Meilman were impressed with Walsh's amassment of 153 diverse references. They concluded with an anecdote about a client who had felt "stuck" but whose condition improved markedly after an offhand recommendation for exercise.[9]

The editor of Issues in Mental Health Nursing, Sandra Thomas, also wrote an editorial in response to Walsh's article. Agreeing with Walsh, Thomas said "the trend toward 15-minute 'medication management appointments' is a formidable barrier to inclusion of patient education about lifestyle change."[10] Thomas found the mention of nature deficit disorder intriguing. And in response to Walsh's call for altruistic service, Thomas said all psychiatric clients could be called upon to serve in a capacity similar to roles played in the organization Alcoholics Anonymous, which "works because members are helping themselves as they help others."[10] Thomas cited Post and Niemark,[29] who "pointed out that we could herald the discovery of a great new drug called 'Give Back—instead of Prozac.' "[10] Thomas closed her editorial with an endorsement of Walsh's article, repeating the call for TLCs to be included in clinical practice.

Books, other literature, and further impact

Greg Bogart, a lecturer in psychology at Sonoma State University,[30] devoted over 2 pages to the article in their book Dreamwork in Holistic Psychotherapy of Depression.[7] According to Bogart, the article's perspective is that increasing time spent in nature is one of the most beneficial TLCs.[7] Bogart highlights the article's emphasis on "exposure to natural light instead of living predominantly in artificial lighting environments, which can disrupt mood, sleep, and diurnal rhythms."[7] Excessive media immersion is also singled out, which "contributes to a feeling of being disconnected from reality, an inability to pay attention or find meaningful engagement with this present world, and a fixation on the stimulation of an unreal reality."[7] Bogart, a psychotherapist, concluded his treatment of the subject by stating that he often shares the principles of TLCs "with clients and encourage[s] them to practice them in their own lives."[31]

Hidaka considers the article as similar to others in the medical literature that have "posited that capitalist values have directly contributed to a decline in social well-being and an increase in psychopathology throughout the western world."[32] Authors Benas & Bryan, in their 2022 book The Resilient Warrior, describe the article as "seminal."[11] According to Google Scholar, the article has been cited over 1050 times as of February 2025.[12]

Additional selected bibliography

- Walsh, Roger; Vaughan, Frances, eds. (1993). Paths Beyond Ego: The Transpersonal Vision. Penguin. ISBN 0-87477-678-3.

- Essential Spirituality: The 7 Central Practices to Awaken Heart and Mind. Wiley. 2000. ISBN 0-471-39216-2.

- Walsh, Roger; Wilber, Ken (2005). A Sociable God: Toward a New Understanding of Religion. Shambhala. ISBN 978-1-59030-224-8.

- The World of Shamanism: New Views of an Ancient Tradition. Llewellyn. 2007. ISBN 978-0-7387-0575-0.

- Shapiro, Deane H.; Walsh, Roger N., eds. (2008) [1984]. Meditation, classic and contemporary perspectives. New York: Aldine. ISBN 978-0-202-36244-1.

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.