Roger Angell

American writer (1920–2022) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Roger Angell (September 19, 1920 – May 20, 2022) was an American essayist known for his writing on sports, especially baseball. He was a regular contributor to The New Yorker and was its chief fiction editor for many years.[1][2] He wrote numerous works of fiction, non-fiction, and criticism, and for many years wrote an annual Christmas poem for The New Yorker.[2] Sportswriter Jane Leavy called him "the Babe Ruth of baseball writers."[3]

Roger Angell | |

|---|---|

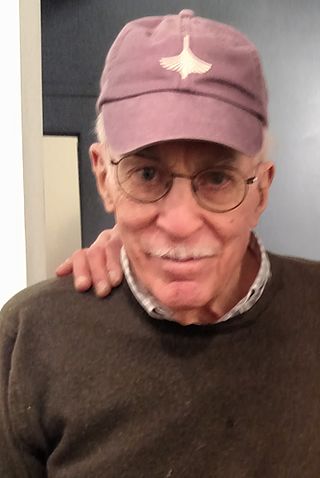

Angell in 2015 | |

| Born | September 19, 1920 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | May 20, 2022 (aged 101) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation | Author |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

| Genre | Sports journalism |

| Notable awards | PEN/ESPN Lifetime Achievement Award for Literary Sports Writing (2011) BBWAA Career Excellence Award (2014) |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

Early life and education

Born on September 19, 1920, in Manhattan, New York,[4][5] Angell was the son of Katharine Sergeant Angell White, The New Yorker's first fiction editor, and the stepson of renowned essayist E. B. White, but he was raised for the most part by his father, Ernest Angell, an attorney who became head of the American Civil Liberties Union.[6][7][8]

After graduating in 1938 from the Pomfret School, he attended Harvard College.[9] He served in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II.[10]

Career

Summarize

Perspective

In 1948, Angell was employed at Holiday Magazine, a travel magazine that featured literary writers.[11] His earliest published works were pieces of short fiction and personal narratives, several of which were collected in The Stone Arbor and Other Stories (1960) and A Day in the Life of Roger Angell (1970).[12]

Angell first contributed to The New Yorker while serving in Hawaii as editor of an Air Force magazine; his short story titled "Three Ladies in the Morning" was published in March 1944. He became The New Yorker's fiction editor in the 1950s, occupying the same office as his mother,[13] and continued to write for the magazine until 2020. "Longevity was actually quite low on his list of accomplishments", wrote his colleague David Remnick. "He did as much to distinguish The New Yorker as anyone in the magazine's nearly century-long history. His prose and his editorial judgment left an imprint that's hard to overstate."[14]

He first wrote professionally about baseball in 1962, when New Yorker editor William Shawn had him travel to Florida to write about spring training.[2][8] His career as a baseball writer coincided with the first season of the New York Mets. His style of baseball writing was inspired, he said, by John Updike's article on Ted Williams's farewell to fans at Fenway Park, "Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu". Angell said "John had already supplied my tone, while also seeming to invite me to try for a good sentence now and then, down the line.”[4] His first two baseball collections were The Summer Game (1972) and Five Seasons (1977).[15] These were followed by Late Innings (1982) and Season Ticket: A Baseball Companion (1988).

Angell has been called the "Poet Laureate of baseball" but he disliked the term.[2][8] In a review of Once More Around the Park for the Journal of Sport History, Richard C. Crepeau wrote that "Gone for Good", Angell's essay on the career of Steve Blass,[a] "may be the best piece that anyone has ever written on baseball or any other sport".[17] Another essay of Angell's, "The Web of the Game", about the epic pitchers' duel between future major-league All-Stars (and eventual teammates) Ron Darling and Frank Viola in the 1981 NCAA baseball tournament, was called "perhaps the greatest baseball essay ever penned" by ESPN journalist Ryan McGee in 2021.[18] Angell contributed commentary to the Ken Burns series Baseball, in 1994.[19]

Personal life and death

Angell was married three times. He had two daughters, Callie and Alice, with his first wife, Evelyn Baker, to whom he was married for 19 years before divorcing.[20] Angell had a son, John Henry, with his second wife, Carol Rogge. After 48 years of marriage, Carol Angell died on April 10, 2012, at the age of 73 of metastatic breast cancer.[21] In 2014, he married Margaret "Peggy" Moorman.[13][22]

His daughter Callie, an authority on the films of Andy Warhol, died by suicide on May 5, 2010, in Manhattan, where she worked as a curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art; she was 62.[23] In a 2014 essay, he mentioned her death – "the oceanic force and mystery of that event" – and his struggle to comprehend that "a beautiful daughter of mine, my oldest child, had ended her life".[24]

Angell died of congestive heart failure at his home in Manhattan on May 20, 2022, at the age of 101.[4][13][5]

Awards and legacy

Summarize

Perspective

David Remnick said, “I’m not sure there’s ever been a writer so strong, and an editor so important, all at once, at a magazine since the days of H. L. Mencken running The American Mercury,” adding “Roger was a vigorous editor, and an intellect with broad tastes.”[4] Per his New York Times obituary, "Like his mother, Mr. Angell became a New Yorker fiction editor, discovering and nurturing writers, including Ann Beattie, Bobbie Ann Mason and Garrison Keillor. For a while he occupied his mother’s old office — an experience, he told an interviewer, that was 'the weirdest thing in the world.' He also worked closely with writers like Vladimir Nabokov, John Updike, Donald Barthelme, Ruth Jhabvala and V.S. Pritchett."[4]

Angell received a number of awards for his writing, including the George Polk Award for Commentary in 1980,[25] the Kenyon Review Award for Literary Achievement in 2005 along with Umberto Eco,[26] and the inaugural PEN/ESPN Lifetime Achievement Award for Literary Sports Writing in 2011.[27] He was a long-time ex-officio member of the council of the Authors Guild,[25] and was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2007.[28] His article This Old Man in The New Yorker[24] on his "challenges and joys of being 93"[29] garnered the National Magazine Award for Essays and Criticism in 2015.[30]

He was inducted into the Baseball Reliquary's Shrine of the Eternals in 2010,[31][32] and he was the 2014 recipient of the J. G. Taylor Spink Award, now known as the BBWAA Career Excellence Award, of the Baseball Writers' Association of America;[33][34] despite being a New Yorker writer, he was nominated by the San Francisco–Oakland chapter.[35] In 2015 he was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters,[36] a unique combination with the Baseball Hall of Fame.[14]

Ross Douthat named Late Innings, The Summer Game and Five Seasons as influences: "I can’t point to any specific philosophy or perspective on contemporary America that I arrived at from reading, re-reading, and re-re-reading Angell’s luminous accounts of baseball seasons past. But if I were to make a list of writers who taught me how to write, he’d be near the top of it."[37] Michael Chabon names Angell and Jan Morris as "two of my favorite authors who are primarily writers of non-fiction."[38]

Angell has four pieces excerpted in the Library of America volume Baseball: A Literary Anthology, more than any other author. Editor Nicholas Dawidoff quotes a letter Angell's stepfather, E. B. White, wrote to Angell: "It's new and exciting to have someone exploring baseball at the depth you have ventured into." Dawidoff writes:

Angell's achievement was to turn quotidian baseball writing into belles lettres. In so doing he became the preeminent baseball writer of our era, a generous, appreciative, meticulous observer whose descriptions of the game are set forth with grace, brio, and wit. (Who else would refer to "the vast pastel conch of Dodger Stadium"?) Angell has Wagnerian range (Honus, that is); he is a master capable of vivid excursions into the profile (see Bob Gibson); he can make games he never saw breathtaking in their excitement (witness the 1986 National League playoffs); and he often reflects on matters philosophical ("The Interior Stadium" is the consummate baseball essay). He can write at length and, what is often more difficult, can write in brief.[39]

Bibliography

- ——— (1960). The Stone Arbor and Other Stories. Boston: Little, Brown.

- ——— (1970). A Day In the Life of Roger Angell. New York: Viking Press.

- ——— (1972). The Summer Game. New York: Viking Press.

- ——— (1977). Five Seasons: A Baseball Companion. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-22743-2.

- ——— (1982). Late Innings: A Baseball Companion. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-42567-8.

- ——— (1988). Season Ticket: A Baseball Companion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-38165-7.

- ——— (1991). Once More Around the Park: A Baseball Reader. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-36737-2.

- ——— (2002). A Pitcher's Story: Innings with David Cone. New York, NY: Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0446678469., about the New York Yankees pitcher David Cone

- ——— (2003). Steve Kettmann (ed.). Game Time: A Baseball Companion. Harcourt Trade Publishers. ISBN 978-0-151-00824-7., introduction by Richard Ford

- ——— (2006). Let Me Finish. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-15-603218-6.

- ——— (2015). This Old Man: All in Pieces. New York, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0385541138.

Notes

- Originally published as "Down the Drain"[16]

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.