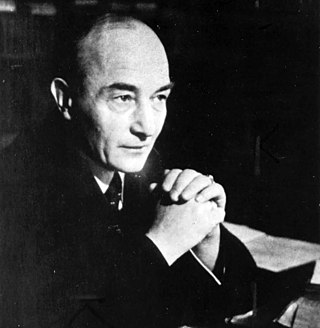

Robert Musil

Austrian philosophical writer (1880–1942) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Robert Musil (German: [ˈʁoːbɛʁt ˈmuːzɪl]; 6 November 1880 – 15 April 1942) was an Austrian philosophical writer. His unfinished novel, The Man Without Qualities (German: Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften), is generally considered to be one of the most important and influential modernist novels.

Robert Musil | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 6 November 1880 Klagenfurt, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 15 April 1942 (aged 61) Geneva, Switzerland |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer, playwright |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Alma mater | University of Berlin |

| Period | 1905–1942 |

| Literary movement | Modernism |

| Notable works | The Confusions of Young Törless The Man Without Qualities |

| Signature | |

| |

Family

Musil was born in Klagenfurt, Carinthia, the son of engineer Alfred Edler Musil (1846, Temeswar/Timișoara – 1924) and his wife Hermine Bergauer (1853, Linz – 1924). The orientalist Alois Musil ("The Czech Lawrence") was his second cousin.[1]

Soon after his birth, the family moved to Komotau/Chomutov in Bohemia, and in 1891 Musil's father was appointed to the chair of Mechanical Engineering at the German Technical University in Brünn/Brno and, later, he was raised to hereditary nobility in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He was baptized Robert Mathias Musil and his name was officially Robert Mathias Edler von Musil from 22 October 1917, when his father was ennobled (made Edler), until 3 April 1919, when the use of noble titles was forbidden in Austria.

Early life

Musil was short in stature, but strong and skilled at wrestling, and by his early teens, he proved to be more than his parents could handle. They sent him to a military boarding school at Eisenstadt (1892–1894) and then Hranice (1894–1897). The school experiences are reflected in his first novel Die Verwirrungen des Zöglings Törless (The Confusions of Young Törless).

Youth and studies

Summarize

Perspective

After graduation Musil studied at a military academy in Vienna during the fall of 1897, but then switched to mechanical engineering, joining his father's department at the Technical University in Brno. During his university studies, he studied engineering by day, and at night, read literature and philosophy and went to the theatre and art exhibitions. Friedrich Nietzsche, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Ernst Mach were particular interests of his university years.[2] Musil finished his studies in three years and, in 1902–1903, served as an unpaid assistant to Professor of Mechanical Engineering Carl von Bach, in Stuttgart. During that time, he began work on Young Törless.

He also invented Musilscher Farbkreisel, the Musil color top, a motorised device for producing mixed colours by additive colour-mixing with two differently colored, sectored, rotating discs. This was an improvement over earlier models, allowing a user to vary the proportions of the two colors during rotation and to read off those proportions precisely.[3]

Musil's sexual life around the turn of the century, according to his own records, was mainly with a prostitute, which he treated partly as an experimental self-experience.[4] But he also was infatuated with the pianist and mountaineer Valerie Hilpert, who assumed mystical features.[5] In March 1902, Musil underwent treatment for syphilis with mercury ointment. During this time, his several years of relationship began with Hermine Dietz, the 'Tonka' of his own novel, published in 1923. Hermine's syphilitic miscarriage in 1906 and her death in 1907 may have been due to infection from Musil.[6]

Musil grew tired of engineering and what he perceived as the limited world-view of the engineer. He launched himself into a new round of doctoral studies (1903–1908) in psychology and philosophy at the University of Berlin under Professor Carl Stumpf. In 1905, Musil met his future wife, Martha Marcovaldi (née Heimann, 21 January 1874 – 6 November 1949). She had been widowed and remarried, with two children, and was seven years older than Musil. His first novel, Young Törless, was published in 1906.

Author

Summarize

Perspective

In 1909, Musil completed his doctorate, with a thesis on the philosopher Ernst Mach, and Professor Alexius Meinong offered him a position at the University of Graz, which he turned down to concentrate on writing. Over the next two years, he wrote and published two stories, ("The Temptation of Quiet Veronica" and "The Perfecting of a Love") collected in Vereinigungen (Unions) published in 1911. During the same year, Martha's divorce was completed, and Musil married her. As she was Jewish and Musil Roman Catholic, they both converted to Protestantism as a sign of their union.[7] Until then, Musil had been supported by his family, but he now found employment first as a librarian in the Technical University of Vienna and then in an editorial role with the Berlin literary journal Die neue Rundschau. He also worked on a play entitled Die Schwärmer (The Enthusiasts), which was published in 1921.

When World War I began, Musil joined the army and was stationed first in Tirol and then at Austria's Supreme Army Command in Bozen (ital. Bolzano). In 1916, Musil visited Prague and met Franz Kafka, whose work he held in high esteem. After the end of the war and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Musil returned to his literary career in Vienna. He published a collection of short stories, Drei Frauen (Three Women), in 1924. He also admired the Bohemian poet Rainer Maria Rilke, whom Musil called "great and not always understood" at his memorial service in 1927 in Berlin. According to Musil, Rilke "did nothing but perfect the German poem for the first time", but by the time of his death, Rilke had turned into "a delicate, well-matured liqueur suitable for grown-up ladies".[8] However, his work is "too demanding" to be "considered relaxing".[9]

In 1930 and 1933, his masterpiece, The Man Without Qualities (Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften) was published in Berlin[10] in two volumes consisting of three parts, running into 1,074 pages: Volume 1 (Part I: A Sort of Introduction, and Part II: The Like of It Now Happens) and 605-page unfinished Volume 2 (Part III: Into the Millennium (The Criminals)).[11] Part III did not include the 20 chapters withdrawn from Volume 2 of 1933 in printer's galley proofs. The novel deals with the moral and intellectual decline of the Austro-Hungarian Empire through the eyes of the book's protagonist, Ulrich, an ex-mathematician who has failed to engage with the world around him in a manner that would allow him to possess qualities. It is set in Vienna on the eve of World War I.

The Man Without Qualities brought Musil only mediocre commercial success. Although he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature, he felt that he did not receive the recognition he deserved. He sometimes expressed annoyance at the success of better known colleagues such as Thomas Mann or Hermann Broch, who admired his work deeply and tried to shield him from economic difficulties and encouraged his writing even though Musil initially was critical of Mann.[12]

In the early 1920s, Musil lived mostly in Berlin. In Vienna, Musil was a frequent visitor to Eugenie Schwarzwald's salon (the model for Diotima in The Man Without Qualities). In 1932, the Robert Musil Society was founded in Berlin on the initiative of Mann. In the same year, Mann was asked to name outstanding contemporary novels, and he cited only one, The Man Without Qualities.[citation needed] In 1936, Musil suffered his first stroke, while swimming.[13]

Thought

Summarize

Perspective

The fundamental problem Musil confronts in his essays and fiction is the crisis of Enlightenment values that engulfed Europe during the early twentieth century.[14] He endorses the Enlightenment project of emancipation, while at the same time examining its shortcomings with a questioning irony.[14] Musil believed that the crisis required a renewal in social and individual values that, accepting science and reason, could liberate humanity in beneficent ways.[14] Musil wrote:

After the Enlightenment most of us lost courage. A minor failure was enough to turn us away from reason, and we allowed every barren enthusiast to inveigh against the intentions of a d'Alembert or a Diderot as mere rationalism. We beat the drums for feeling against intellect and forgot that without intellect ... feeling is as dense as a blockhead (dick wie ein Mops ist).[15]

He took aim at the ideological chaos and misleading generalizations about culture and society promoted by nationalist reactionaries. Musil wrote a withering critique of Oswald Spengler entitled "Mind and Experience: a Note for Readers Who Have Escaped the Decline of the West (Geist und Erfahrung: Anmerkung für Leser, welche dem Untergang des Abendlandes entronnen sind)", in which he dismantles the latter's misunderstanding of science and misuse of axiomatic thinking, to try to understand human complexity and promote a deterministic philosophy.[16]

He deplored the social conditions under the Austro-Hungarian Empire and foresaw its disappearance.[17] Surveying the upheavals of the 1910s and 1920s, Musil hoped that Europe could find an internationalist solution to the "dead end of imperial nationalism".[18] In 1927, he signed a declaration of support for the Austrian Social Democratic Party.[19]

Musil was a staunch individualist who opposed the authoritarianism of both right and left. A recurring theme in his speeches and essays through the 1930s is the defense of the autonomy of the individual against the authoritarian and collectivist ideas then prevailing in Germany, Italy, Austria, and Russia.[20] He participated in the anti-fascist International Writers' Congress for the Defense of Culture in 1935 in which he spoke in favor of artistic independence against the claims of the state, class, nation, and religion.[21]

Later life

The last years of Musil's life were dominated by Nazism and World War II: the Nazis banned his books. He saw early Nazism first-hand while he was living in Berlin from 1931 to 1933. In 1938, when Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany, Musil and his Jewish wife, Martha, left for exile in Switzerland, where he died at the age of 61. Martha wrote to Franz Theodor Csokor that he had suffered a stroke.[22]

Only eight people attended his cremation. Martha cast his ashes into the woods of Mont Salève.[23] From 1933 to his death, Musil had been working on Part III of The Man Without Qualities. In 1943 in Lausanne, Martha published a 462-page collection of material from his literary remains, including the 20 galley chapters withdrawn from Part III before Volume 2 appeared in 1933,[10] as well as drafts of the final incomplete chapters and notes on the development and direction of the novel.[11] She died in Rome in 1949.

Legacy

After his death, Musil's work was almost forgotten. His writings began to reappear during the early 1950s. The first translation of The Man Without Qualities in English was published by Ernst Kaiser and Eithne Wilkins in 1953, 1954, and 1960. An updated translation by Sophie Wilkins and Burton Pike, containing extensive selections from unpublished drafts, appeared in 1995.[24] Musil's work, including its philosophical aspects, has received more attention since then.[25] Milan Kundera said, "No novelist is dearer to me,"[26] and Thomas Bernhard said he was "addicted" to Musil.[citation needed] One of the most important philosophy journals, The Monist, published a special issue on "The Philosophy of Robert Musil" in 2014, edited by Bence Nanay.[27]

Timeline

- 1880 November 6, Robert Musil born in Klagenfurt. Mother Hermine, father engineer Alfred Musil.

- 1881–1882 The Musils move to Chomutov in Bohemia.

- 1882–1891 The Musils move to Steyr (Austria). Robert attends the elementary school and the first grade of the gymnasium.

- 1891–1892 Move to Brno. Attends the Realschule.

- 1892–1894 Attends the military boarding school in Eisenstadt.

- 1894–1897 Attends the military Militär-Oberrealschule in Hranice (present-day in the Czech Republic) during his working with artillery Musil discovers his interest in technique.

- 1897 Attends the Technische Militärakademie in Vienna.

- 1898–1901 Quit officer training and starts studies at the Technical University in Brno. His father had been a professor there since 1890. First literary attempt and first diary notations.

- 1901 doctoral examinations.

- 1901–1902 Musil enlists in the infantry regiment of Freiherr von Hess Nr. 49 in Brno.

- 1902–1903 Move to Stuttgart to work at the university. Works on his first novel, Die Verwirrungen des Zöglings Törless

- 1903–1908 Takes up studies in philosophy; his majors are "logic and experimental psychology".

- 1905 In his diaries he makes the first notes that develop into Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften.

- 1906 Die Verwirrungen des Zöglings Torless is published. Developed an apparatus to research colour experience in people.

- 1908 Beiträge zur Beurteilung der Lehren Machs is the title of his doctoral thesis. Declines an offer to upgrade his last military rank to an equal civilian rank in favour of writing.

- 1908–1910 Works in Berlin as an editor for the magazine Pan and on his Vereinigungen and Die Schwärmer.

- 1911–1914 Librarian at the Technical University of Vienna.

- 1911 on 15 April Musil marries Martha Marcovaldi. Vereinigungen is published.

- 1912–1914 Editor for several literary magazines, including Neue Rundschau.

- 1914–1918 During World War I, Musil is officer at the Italian front. Decorated several times.

- 1916–1917 July–April: publishes the "Soldaten-Zeitung".

- 1917 On 22 October, Alfred Musil was hereditary ennobled as Alfred Edler von Musil, making Robert Musil also a member of the nobility until it was abolished less than two years later.[28]

- 1918 Takes up writing again.

- 1919–1920 Works for the Information Service of the Austrian foreign department in Vienna.

- 1920 April–June: lives in Berlin. Meets Ernst Rowohlt, who will become his publisher in 1923.

- 1920–1922 Adviser for army matters in Vienna.

- 1921–1931 Works as theatre critic, essayist, and writer in Vienna. Works on Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften.

- 1921 The play Die Schwärmer is published.

- 1923–1929 Is vice-president of Schutzverband deutscher Schriftsteller in Österreich. Meets Hugo von Hofmannsthal, who is president of the foundation.

- 1923 Awarded the Kleist Prize for Die Schwärmer. On 4 December Vinzenz und die Freundin bedeutender Männer is premièred in Berlin.

- 1924 on 24 January his mother died and on 1 October his father died. Awarded the art prize of the city of Vienna. Drei Frauen is published.

- 1927 Delivers a speech following the death the previous year of Rainer Maria Rilke in Berlin.

- 1929 4 April première of Die Schwärmer. Over Musil's objections, the play is shortened and, according to him, incomprehensible. In the autumn awarded the Gerhart Hauptmann award.

- 1930 The first two parts of Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften are published. In spite of critical support, Musil's financial situation is precarious.

- 1931–1933 Lives and works in Berlin.

- 1932 Foundation of a Musil-Gesellschaft by Kurt Glaser in Berlin. The foundation aims to provide Musil with the means necessary to continue working on his novel. At the end of the year the third part of Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften is published.

- 1933 in May Musil leaves Berlin with his wife, Martha. Via Karlovy Vary and Potštejn in Czechoslovakia they reach Vienna.

- 1934–1938 After the dismantling of the Berlin Musil-Gesellschaft, a new one is founded in Vienna.

- 1935 Lecture for the Internationalen Schriftstellerkongress für die Verteidigung der Kultur in Paris.

- 1936 Publishes his collection of thoughts, observations, and stories Nachlass zu Lebzeiten. Suffers a stroke.

- 1937 on 11 March invited by the Werkbund lecture "On stupidity" in Vienna

- 1938 Via northern Italy Musil and his wife flee to Zürich. Two days after their arrival, on 4 September, they have tea at Thomas Mann's home in Küsnacht.

- 1939 In July moves to Geneva. Musil continues to work on his novel and grows lonelier with exile. Thanks to the Zürich vicar Robert Lejeune, Musil receives some financial support, including from the American couple, Henry Hall and Barbara Church. In Germany and Austria Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften and Nachlaß zu Lebzeiten are banned. All his works are banned in 1941.

- 1942 April 15, Musil dies in Geneva.

- 1943 Martha Musil publishes the unfinished remains of Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften.

- 1952–1957 Adolf Frisé publishes the complete works of Robert Musil at Rowohlt.

Bibliography

Summarize

Perspective

Works related to Robert Musil at Wikisource

Works related to Robert Musil at Wikisource- Die Verwirrungen des Zöglings Törleß (1906). The Confusions of Young Törless, novel

- Vereinigungen (1911). A collection of two short stories: "The Temptation of Quiet Veronica" and "The Perfecting of Love"

- Unions: Two Stories, translated with an introduction by Genese Grill (New York: Contra Mundum Press: 2019)

- Intimate Ties: Two Novellas, trans. Peter Wortsman (Archipelago, 2019)

- Die Schwärmer (1921). The Enthusiasts, play, trans. Andrea Simon (New York: Performance Arts Journal Publications, 1983)

- Vinzenz und die Freundin bedeutender Männer (1924). Vinzenz and the Girlfriend of Important Men, play

- Drei Frauen (1924). Three Women, a collection of three novellas "Grigia", "The Portuguese Lady", and "Tonka"

- Nachlaß zu Lebzeiten (1936). Posthumous Papers of a Living Author, trans. Peter Wortsman (Eridanos Press, 1988)

- A collection of short prose pieces.

- Über die Dummheit (1937). About Stupidity, lecture

- Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften (1930, 1933, 1943). The Man Without Qualities

Compilations in English

- Tonka and Other Stories, trans. Eithne Wilkins and Ernst Kaiser (1965); later reprinted as Five Women (1986)[29]

- Compiles the five stories of Vereinigungen and Drei Frauen

- Precision and Soul: Essays and Addresses, edited and translated by Burton Pike and David S. Luft (The University of Chicago Press, 1990)

- Thought Flights, translated with an introduction by Genese Grill (New York: Contra Mundum Press, 2015)

- Agathe, or the Forgotten Sister, trans. Joel Agee (New York Review Books, 2019). This is "a selection of these chapters [from the last third of The Man Without Qualities], two of which have not previously appeared in English". (p. xxxii.)

- Theater Symptoms: Plays & Writings on Drama, translated with an introduction & preface by Genese Grill (New York: Contra Mundum Press, 2020)

- Literature and Politics: Selected Writings, trans. Genese Grill (New York: Contra Mundum Press, 2023)

In popular culture

Die Verwirrungen des Zöglings Törleß was later made into the movie Der junge Törless (1966).

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.