Rick Moody

American novelist From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Hiram Frederick Moody III (born October 18, 1961) is an American novelist and short story writer best known for the 1994 novel The Ice Storm, a chronicle of the dissolution of two suburban Connecticut families over Thanksgiving weekend in 1973, which brought him widespread acclaim, became a bestseller, and was made into the film The Ice Storm. Many of his works have been praised by fellow writers and critics alike.

Rick Moody | |

|---|---|

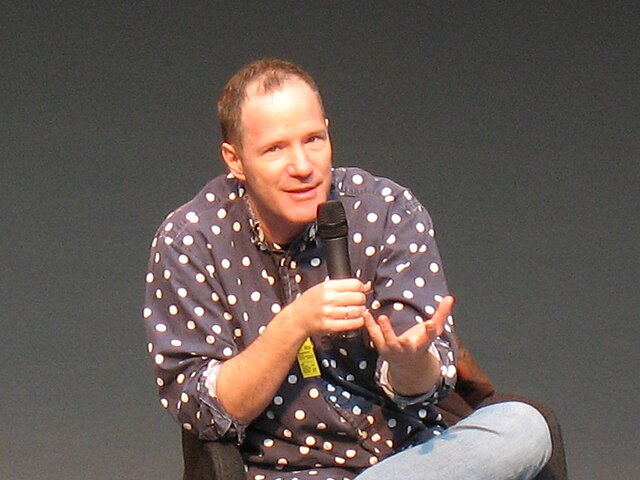

Moody in Lyon, France - May 2009 | |

| Born | Hiram Frederick Moody III October 18, 1961 New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Education | St. Paul's School Brown University Columbia University (MFA) |

| Period | 1992–present |

Early life and education

Moody was born in New York City to banker and investment strategist[1] Hiram Frederick Moody, Jr., and Margaret Maureen, daughter of Francis Marion Flynn, president and publisher of The New York News. The Moody family were resident in Maine for generations from around 1680; Moody's father was born there, but his parents subsequently lived at Winchester, Massachusetts.[2][3][4] Moody grew up in several Connecticut suburbs, including Darien and New Canaan, where he later set stories and novels. He graduated from St. Paul's School in New Hampshire and Brown University.

He received a Master of Fine Arts degree from Columbia University in 1986; nearly two decades later he would criticize the program in an essay in The Atlantic Monthly.[5] Soon after finishing his thesis, he checked himself into a mental hospital for alcoholism.[6]

Career

Summarize

Perspective

Once sober and while working for Farrar, Straus and Giroux, he wrote his first novel, 1992's Garden State, about young people growing up in the industrial wasteland of northern New Jersey, where he was living at the time. In his introduction to the 1997 reprint of the novel, he called it the most "naked" thing he has written.[7]

Moody's second novel, 1994's The Ice Storm, was his critically praised breakthrough. Adam Begley, writing for the Chicago Tribune, called it "A bitter and loving and damning tribute to the American family... This is a good book, packed with keen observation and sympathy for human failure".[8] His third novel, 1997's Purple America also received praise. Occurring over a single weekend, the story of Hex Radcliffe's visit to suburban Connecticut was described by the New York Times as "breathtaking...The novel is wonderfully convincing about the contrary, almost arbitrary shifts that seem to lie at the heart of human feeling."[9]

2001's Demonology, a short story collection, received particular attention for its title story, of which Nicci Gerrard wrote: "It is about the death of a sister, whose life he offers to us in snapshots: her childhood, her motherhood, her sudden death. 'I should have a better ending,' he says. 'I shouldn't say her life was short and often sad, I shouldn't say she had her demons, as I do too...' It is tempting to think of this beautiful and melancholy coda to Rick Moody's stories as the appearance of the author, stepping out of the shadows at last, particularly since the first story in the collection is also, though much more obliquely, about the death of a beloved sister."[10]

Moody's memoir The Black Veil (2002) won the NAMI/Ken Book Award and the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for the Art of the Memoir. The Diviners was released in 2005. Little, Brown and Company, the publisher of The Diviners, changed the cover after the galleys came out because women reacted negatively to it. The original cover showed a Conan the Barbarian-type image in technicolor orange; the new cover uses that same image, but frames it as a scene on a movie screen.[11] The Diviners was followed in 2007 by Right Livelihoods, a collection of three novellas published in Britain and Ireland as The Omega Force. The Four Fingers of Death was released July 28, 2010 by Little, Brown and Company. In 2012, he won Italy's Fernanda Pivano Award. 2015's Hotels of North America, his most recent novel, was named a best book of the year by NPR and the Washington Post.[12]

His second memoir, The Long Accomplishment was published in 2019.[13]

In addition to his fiction, Moody is a musician and composer. He belongs to a group called the Wingdale Community Singers, which he describes as performing "woebegone and slightly modernist folk music, of the very antique variety."[14] Moody composed the song "Free What's-his-name," performed by Fly Ashtray on their 1997 EP Flummoxed,[15] collaborated with One Ring Zero on the EP Rick Moody and One Ring Zero in 2004, and also contributed lyrics to One Ring Zero's albums As Smart As We Are, Memorandum, and Planets.[16]

In 2006, an essay by Moody was included in Sufjan Stevens's box-set Songs for Christmas.

In 2013, he published the first interview with David Bowie after the release of The Next Day.[17] In 2016, he co-wrote three songs with Tanya Donnely on her new Swan Song Series album.[18]

in 2007, when asked by the New York Times Book Review what he thought was the best book of American fiction from 1975 to 2000, Moody chose Grace Paley's The Collected Stories.[19]

In 2001, Rick Moody co-founded the New York Public Library's Young Lions Fiction Award with Ethan Hawke, Hannah McFarland, and Jennifer Rudolph Walsh.[20]

Moody is a co-host, along with One Ring Zero's Michael Hearst, for the 18:59 Podcast series.[21]

Personal life

He lives in Brooklyn and Dutchess County, and he is married to the visual artist Laurel Nakadate.[22]

Awards

Garden State won the Pushcart Editor's Choice Award. Moody has since received the Addison Metcalf Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Paris Review Aga Khan Prize, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, Esquire, Conjunctions, Harper's, Details, The New York Times, and Grand Street.

Praise

Summarize

Perspective

This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. (May 2012) |

Literary critics have praised Moody's writing. In 1999 The New Yorker chose him as one of America's most talented young writers, placing him on their "20 Writers for the 21st Century" list.[citation needed]

Of the novel The Ice Storm (later produced as the movie starring Sigourney Weaver), Hungry Mind Review commented that it “works on so many levels, and is so smartly written, that it should establish Rick Moody as one of his generation's bellwether voices."[23] The London Sunday Times wrote "This is a blackly funny, beautifully written novel. It is also remarkably mature, containing far more insights about family life and far more wisdom than any 29-year-old author should reasonably possess."[24]

Reviews of Moody’s novel Purple America continued in this vein. Salon commented: "Reading Purple America can feel like dancing a quadrille with four very different partners. On we go, propelled from consciousness to consciousness by Moody's prodigious gift for ventriloquism and large, supple vocabulary."[citation needed] Details was also positive: "You come up gasping on the last page."[citation needed] Publishers Weekly called it "ambitious, stylistically dazzling and heartfelt."[25] Booklist states: "Closely interknitting his narrative with the lyrical, soaring monologues of all the key players, Moody effortlessly moves from one striking passage to the next....it's the characters' voices, so full of urgency and distress, that are unforgettable."[26] And The Paris Review wrote that it was with Purple America that "Moody’s reputation as a prose stylist began to be cast. Purple America’s surgically deft formal construction, its loping, labyrinthine sentences and stunning ear for both the comic and dramatic (often within the same breath) press the reader through a weekend in the life of the Raitliffes, a Connecticut family—foremost, Billie Raitliffe, late-term victim of a degenerative nerve disease and mother of Hex, the alcoholic, stuttering hero. As the novel asserts at the end of the first chapter: “if he’s a hero, then heroes are five-and-dime, and the world is as crowded with them as it is with stray pets, worn tires, and missing keys.”

In 2007, The Washington Post reviewed Moody’s collection of novellas Right Livelihoods, describing "The Albertine Notes" as “one of the best stories to appear in the new millennium; it underscores that Rick Moody is one of our best writers.”[27] Irish weekly The Sunday Business Post called the story “a symbolic reaction to the crisis of instability in American identity today” and remarked that the collection as a whole “brilliantly reflects the unease and baroque insecurities of the post-9/11 nation."[28]

Michael Chabon and Thomas Pynchon gave high praise for the memoir, The Black Veil, the former calling it "a unique blend of wrenching emotion and human playfulness," the latter saying Moody "writing with boldness, humor, generosity of spirit, and a welcome sense of wrath, takes the art of the memoir an important step into its future."

His 2005 novel The Diviners received praise as well. "If you like watching the smartest kid in the room do his stuff," The Washington Post wrote, "The Diviners is like a Broadway musical filled with nothing but showstoppers, as Moody performs one bravura set piece after another.[29] Brooke Allen, writing for The Wall Street Journal, said that "Rick Moody is one of the most prodigiously talented writers in America...like a master ventriloquist, Mr. Moody fills "The Diviners" with stunning little monologues...In the novel's most impressive display of technical prowess, Mr. Moody even puts himself inside the head of an autistic boy—and makes us feel that he has gotten it right."[30]

The Review of Contemporary Fiction, in their June 2003 issue, says of Moody's writing:

"Within Moody's fictional treatments, the reader is necessarily one step removed from experience. We are engaged within a tight fuselage-world of the rendered text, an intricate and highly original language system wherein lurks characters sustained by the exertion of words, like the music sustained by the exertion of piano keys. Indeed, Moody's characters are like word-chords whose considerable tribulations and emotional woundings are never the central fact of the text, but rather convincing casings, occasions to press ink on paper. Voices emerge--language projections that ignite from plot moments, from brutal experience set to the available music of language, characters finally as sonic events who inhabit a geography of print."[citation needed]

Esquire describes Moody as "that rare writer who can make the language do tricks and still suffuse his narrative with soul."[31]

Lydia Millet, in a 2001 article for The Village Voice, described Moody as "equipped with subtle but powerful typographic tools—the vibrant and pervasive Bernhardian italic phrase, pregnant with meaning, the elegant Joycean em dash denoting dialogue—Moody strikes me as a self-styled avenging angel of highbrow literary cool. Underneath the Clark Kentish exterior lurks a crypto-Superman schooled in semiotics and steeped in pop culture, one eyebrow permanently raised at the unsightly stupidity of the masses."[citation needed]

Janet Burroway, in a 2001 article for The New York Times, wrote that Moody "has been compared to John Cheever, with ample justification. He has the same knockabout whimsy careering into keen lament. But Mr. Moody's work has a distinctive rawness; it's more steeped in rage. He's also funnier, and to that degree less reconciled to the world as he finds it. Cheever had less to forgive; the waterfall of language here is full of toxic sludge. Perhaps this is only to say that John Cheever belonged to midcentury, while Rick Moody is a chronicler of the middle class for the millennium."[9]

His most recent novel, 2015's Hotels of North America, received widespread critical praise. Dwight Garner wrote in The New York Times, "...this is Mr. Moody’s best novel in many years. It’s a little book, a bagatelle, but it’s a little book of irony and wit and heartbreak. It is insightful on topics like the joy of stockpiling hotel hair-care products while also asking the big questions, such as, 'Which man among us is not, most of the time, possessed of the desire to curl himself into a fetal ball.'"[32] Hotels of North America was described by the Washington Post as "formally daring, often very funny and surprisingly moving. It should earn Moody new fans from a millennial cohort that was still in diapers back when he was basking in his early critical acclaim."[33]

Criticism

Summarize

Perspective

Novelist and critic Dale Peck unfavorably reviewed Moody's The Black Veil in The New Republic, a review so harsh it has become infamous in literary circles.[34] Peck began the review with the sentence "Rick Moody is the worst writer of his generation,"[35] arguing that Moody's writing is "pretentious, muddled, derivative, [and] bathetic." Peck has since said of his lede, "When I wrote a sentence like 'Rick Moody is the worst writer of his generation,' in my head, I'm imagining 50 people reading that line. I'm imagining 50 people reading it in context. The very next line, which is an apology for the opening line of the review, says that that line is meaningless."[36] Moody and Peck have since participated in a pie throwing for charity[37] and appeared together on a panel about Thomas Bernhard.[38]

In the online journal The Rumpus, Moody slammed pop-country star Taylor Swift and her music, labeling her lyrics "artificial and repellent" and equating its interest to that of Olestra-based products, Swiffers, tiered Jell-O dessert products, home cosmetic surgery, and rectal bleaching.[39] After commenters objected to Moody's anti-Swift screed, Moody took to Salon and wrote "I am happy, in the end, that a lot of young women like Taylor Swift. I am glad they have music they love, even if I believe they will be bored of her ultimately, just as I once was happy about the Bay City Rollers, or Sweet, or Alice Cooper, or, differently, Kiss, even though I recognized that music was kitsch... But it’s the job of the critic to sort through the collision of contemporary music with the history of the form and to assess music based on more enduring values, which are, it’s true, partly subjective, but which also come to rest on an understanding of what music has been".[40]

Bibliography

Novels

- Garden State (1992)

- The Ice Storm (1994)

- Purple America (1996)

- The Diviners (2005)

- The Four Fingers of Death (2010)

- Hotels of North America (2015)[41]

Short fiction

- Collections

- The Ring of Brightest Angels Around Heaven: A Novella and Stories (1995)

- Demonology (stories, 2001)

- Right Livelihoods: Three Novellas (2007)

- Stories[42]

| Title | Year | First published | Reprinted/collected | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Demonology | |||

Non-fiction

- The Black Veil: A Memoir with Digressions (2002)

- On Celestial Music: And Other Adventures in Listening (2012)

- The Long Accomplishment: A Memoir of Struggle and Hope in Matrimony (2019)

- Satire

- Surplus Value Books: Catalog Number 13 (Illustrated by David Ford) (1999)

Book reviews

| Year | Review article | Work(s) reviewed |

|---|---|---|

| 1997 | "Surveyors of the Enlightenment". Books. The Atlantic Monthly. 280 (1): 106–110. July 1997. | Pynchon, Thomas (1997). Mason & Dixon. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 9780805037586. |

As editor or contributor

- Joyful Noise: The New Testament Revisited (co-editor, with Darcey Steinke, and contributor) (1997)

- The Magic Kingdom, by Stanley Elkin (introduction to the Dalkey Archives trade paperback reprint) (2000)

- A Convergence of Birds: Original Fiction and Poetry Inspired by Joseph Cornell (contributor) (2001)

- The Mayor of Casterbridge, by Thomas Hardy (introduction to the Oxford World's Classics edition) (2002)

- Lithium for Medea, by Kate Braverman (introduction to the Seven Stories Press trade paperback reprint) (2002)

- Twilight: Photographs by Gregory Crewdson (text) (2002)

- "William Gaddis: A Portfolio." Conjunctions #41 (2003)

- Killing the Buddha: A Heretic's Bible (contributor, short fiction envisioning a modern-day Jonah) (2004)

- The Wilco Book (contributor) (2004)

- The Collected Stories of Amy Hempel (introduction) (2006)

- The Flash (contributor) (2007)

- The Changeling by Joy Williams (foreword to Thirtieth Anniversary Edition) (2008)

- The Rumpus (Music blogger) (2009)

- J R, by William Gaddis (introduction to the Dalkey Archive trade paperback reprint) (2012)

Other media

- Moody appeared on Ken Reid's TV Guidance Counselor podcast on December 30, 2015.

Notes

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.