Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Q-PACE

Spacecraft mission to study stellar accretion From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

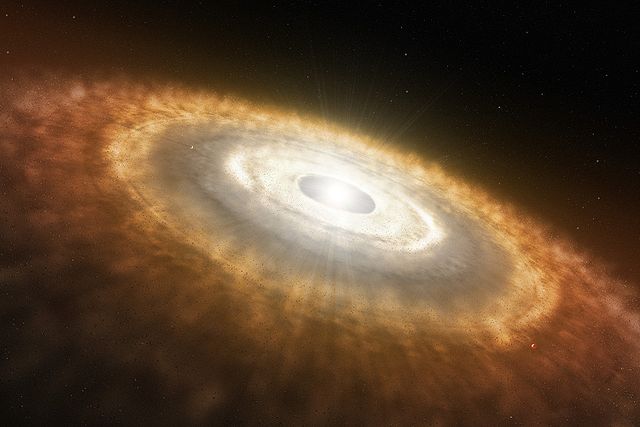

CubeSat Particle Aggregation and Collision Experiment (Q-PACE) or Cu-PACE,[4] was an orbital spacecraft mission that would have studied the early stages of proto-planetary accretion by observing particle dynamical aggregation for several years.[5]

Current hypotheses have trouble explaining how particles can grow larger than a few centimeters. This is called the meter size barrier. This mission was selected in 2015 as part of NASA's ELaNa program, and it was launched on 17 January 2021.[6] As of March 2021, however, contact has yet to be established with the satellite, and the mission was feared to be lost. The mission was eventually terminated.

Remove ads

Overview

Summarize

Perspective

Q-PACE was led by Joshua Colwell at the University of Central Florida and was selected NASA's CubeSat Launch Initiative (CSLI) which placed it on Educational Launch of Nanosatellites ELaNa XX.[7] The development of the mission was funded through NASA's Small Innovative Missions for Planetary Exploration (SIMPLEx) program.[5][8]

Observations of the collisional evolution and accretion of particles in a microgravity environment are necessary to elucidate the processes that lead to the formation of planetesimals (the building blocks of planets), km-size, and larger bodies, within the protoplanetary disk. The current hypotheses of planetesimal formation have difficulties in explaining how particles grow beyond one centimeter in size, so repeated experimentation in relevant conditions is necessary.[9]

Q-PACE was to explore the fundamental properties of low‐velocity (< 10 cm/s (3.9 in/s)) particle collisions in a microgravity environment in an effort to better understand accretion in the protoplanetary disk.[10] Several precursor tests and flight missions were performed in suborbital flights as well as in the International Space Station.[1][11] The small spacecraft does not need accurate pointing or propulsion, which simplified the design.

On 17 January 2021, Q-PACE launched on a Virgin Orbit Launcher One, an air launch to orbit rocket that was dropped from the Cosmic Girl airplane over the Pacific Ocean.[12] As of March 2021, however, contact was not established with the satellite after it reached orbit,[13] and the spacecraft was declared lost and the mission ended.

Remove ads

Objectives

The main objective of Q-PACE was to understand protoplanetary growth from pebbles to boulders by performing long-duration microgravity collision experiments. The specific goals are:[1]

- Quantify the energy damping in multi-particle systems at low collision speeds (< 1 mm/s (0.039 in/s) to 10 cm/s (3.9 in/s))

- Identify the influence of a size distribution on the collision outcome.

- Observe the influence of dust on a multi-particle system.

- Quantify statistically rare events: observe a large number of similar collisions to arrive at a probabilistic description of collisional outcomes.

Remove ads

Method

Q-PACE was a 3U CubeSat with a collision test chamber and several particle reservoirs that contain meteoritic chondrules, dust particles, dust aggregates, and larger spherical particles. Particles will be introduced into the test chamber for a series of separate experimental runs.

The scientists designed a series of experiments involving a broad range of particle size, density, surface properties, and collision velocities to observe collisional outcomes from bouncing to sticking as well as aggregate disruption in tens of thousands of collisions.[9][14] The test chamber will be mechanically agitated to induce collisions that will be recorded by on‐board video for downlink and analysis.[10] Long duration microgravity allows a very large number of collisions to be studied and produce statistically significant data.[1]

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads