Loading AI tools

The Puget Sound Agricultural Company (PSAC), with common variations of the name including Puget Sound or Puget's Sound, was a subsidiary joint stock company formed in 1840 by the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC). Its stations operated within the Pacific Northwest, in the HBC administrative division of the Columbia Department. The RAC-HBC Agreement was signed in 1839 between the Russian-American Company and the HBC, with the British to now supply the various trade posts of Russian America. It was hoped by the HBC governing committee that independent American merchants, previously a major source of foodstuffs for the RAC, would be shut out of the Russian markets and leave the Maritime fur trade.

Because its monopoly license granted by the British Government forbade any activity besides the fur trade, the HBC created the PSAC to sidestep this issue. The PSAC was formed to produce or manufacture enough agricultural and livestock products to meet the Russian supply demands. In correspondence with British officials, the PSAC was long touted as a means to promote the British position in the Oregon boundary dispute with the United States. For years now the British had insisted that the Pacific Northwest be partitioned along the Columbia River, rather than a westward extension of the 49th parallel. This would have left most of modern Washington state under British control, notably the important Puget Sound. Through its company stations, the PSAC would promote settlement by British subjects in this disputed area, although it largely failed in this particular aspect.

The primary company operations were centered at Fort Nisqually and Cowlitz Farm in modern Washington state. At Fort Nisqually (near present-day Olympia, Washington) due to poor soil, the station focused on pastoral operations, including flocks of sheep for wool, cattle herds for beef and cheese manufacturing. Cowlitz Farm was the company's primary center of agricultural production. The company also operated many large farms in the area of Fort Victoria on Vancouver Island.

George Simpson and John McLoughlin were both influential in the events leading to the eventual creation of the PSAC.

The governing committee and its officers were as a practice in consistent contact with members of the British Government. This was a major advantage for the company and gave them important insights into political developments. Simpson and his cohorts knew the general position of the British Government for any potential negotiations with the United States to resolve the Oregon boundary question. The British would continue their previous stance of claiming all territory north of the Columbia River. This policy influenced the location of Fort Vancouver, placed on the northern bank of the Columbia.

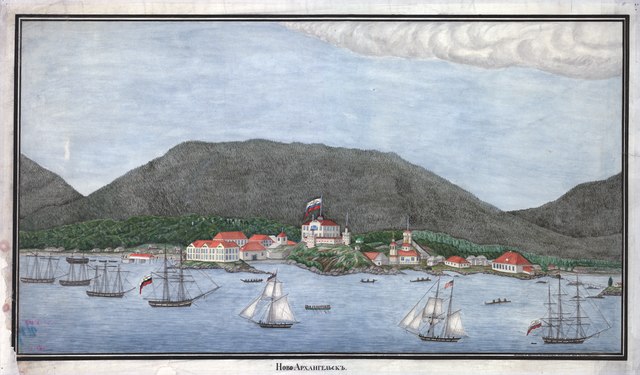

On his second visit to Fort Vancouver in the 1828 through 1829, George Simpson found the area quite promising for further agricultural ventures. Simpson sent his cousin Lt. AEmilius Simpson on the Cadboro to the Russian American capital of Novoarkhangelsk in 1829 to offer large stockpiles of foodstuffs annually to the Russian-American Company. However, the proposal wasn't accepted by Governor of Russian Colonies in America Pyotr Chistyakov. Nonetheless, Simpson and other officers still considered it a viable option, as historian John Semple Galbraith recounted:

If the Hudson's Bay Company could provide the Russians with the supplies they were accustomed to purchase from American ships, one of the supports for American competition in the coastal fur trade would be removed.[1]

"The Oragon Beef & Tallow Company"

The Alta Californian hide and tallow trade greatly influenced John McLoughlin. In 1832 he proposed that HBC officers and employees in the Columbia Department should create a new joint stock company to purchase several hundred cattle from Alta California. Called "The Oragon Beef & Tallow Company," as McLoughlin told his superiors, it was formed "with the view of opening from the Oragon Country an export trade with England and elsewhere in tallow, beef, hides, horns, &c."[1] If the cattle were gathered from Alta California in 1833, McLoughlin projected Fort Vancouver area to have a herd of over 5,000 by 1842. Additionally, he pointed out favorable locations to host these numerous bovines. The valleys of the Willamette, Cowlitz and Columbia were all deemed as appropriate to host upwards of half a million livestock.[1]

The proposal was immediately derided and denied by the HBC governing committee. They feared that if the Oragon Beef and Tallow Company were successful then HBC employees would quit the fur trade to become pastoralists and agriculturalists.[1] While Simpson was favorable to the idea of growing expansive numbers of livestock and farm products, he was decidedly against McLoughlin's proposal of independent operators supplying the provisions for trade in Russian America and the Kingdom of Hawaii. Late in 1834, agreeing to Simpson's idea of the HBC directly overseeing these proposed operations, the committee decided to look for a new location for its central depot for operations on the Pacific Coast. Previous outbreaks of disease at Fort Vancouver worried the administrators, who ordered McLoughlin to thoroughly examine Whidbey Island and other potential locations north of the Columbia River, although he had done neither by 1837.[2]

While the proposed livestock project languished, the HBC pushed for a renewal of its monopoly licence from the British Government, set to expire in 1841. Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company John Pelly highlighted to Secretary of the Colonies Lord Glenelg the benefits the British Empire had for decades received from the HBC in 1837. In this correspondence he promoted the considered, not still not active, livestock and farming operations in the Columbia Department. Once this venture began, Pelly declared, it would maintain "British interests and British influence... as paramount in this interesting part of the Coast of the Pacific."[3] The appeals of Pelly and his cohorts worked, for the HBC received another license in May 1838. The HBC was still only British enterprise allowed to trade with native peoples west of Rupert's Land, but it did not include the right to engage in commercial farming. However, like the previous license granted in 1821, the British Government stressed to not harass any American merchants in the Pacific Northwest.[3]

Throughout the summer and fall of 1838, the HBC held multiple conferences in London. Among those present were George Simpson, John McLoughlin, Governor John Pelly, and other members of the governing committee. Once gathered, the fur merchants and administrators considered future company operations in the Pacific Northwest. Military action by Americans over the Oregon Question appeared to some members assembled as quite likely at the time. This was in no small part due to the legislative work of U.S. Senator Lewis F. Linn. In February 1838, he pushed for the dispatch of a naval force to the Columbia, in addition to offering land grants to interest American settlers. Despite some enthusiasm however, Linn's bill didn't pass receive enough votes in Congress to become law.[3]

RAC-HBC Agreement

Besides considerations about Americans, the company agreed to again pursue a supply contract with the Russian-American Company, an accord that had been desired by Simpson for a decade. Signed in 1839 with the Russian colonial authorities, the RAC-HBC Agreement gave the HBC the obligation to provide enough provisions to supply the various trading stations of Russian America. Having finally secured this financially important agreement, the HBC formally incorporated the Puget Sound Agricultural Company in 1840.

Created to bypass its license to only participate in the fur trade, the PSAC was overseen and staffed with HBC employees. In this way, the PSAC would protect HBC board members and shareholders from accusations and suits resulting from violations of the HBC charter. Besides meeting the new obligations with the Russians, the PSAC was conceived to support British claims in the Pacific Northwest.[4] These claims were centered on an area north of the Columbia River but south of the 49th parallel, located within modern Washington state. The PSAC had two stations within this area, Fort Nisqually and Cowlitz Farm.

Labor recruitment

Starting with Étienne Lucier in 1829, a steady number of primarily French-Canadian employees of the HBC became farmers in the Willamette Valley. Their agricultural products were sold to the HBC and continued to use Fort Vancouver as their source of needed supplies and household goods. These men eventually contacted bishop Provencher through McLoughlin and requested priests to be sent. Eventually Provencher selected François Norbert Blanchet and Modeste Demers as capable for traveling to the distant Willamette Valley. In correspondence to HBC officials he requested overland transportation for the two men in 1837. The fur merchants saw this as a useful opportunity to further the still paper PSAC. French-Canadians farmers residing in the Willamette Valley could potentially be induced to relocate to more favorable locations north of the Columbia.[5] The Catholic priests could additionally counter any Methodist influence over the French-Canadians by superintendent Jason Lee. However, they utterly failed to convince any farmer to leave the Willamette Valley.[5]

The failure to get any Willamette farmers to relocate didn't deter the HBC administration. According to the plans established in September 1839, by 1841 the PSAC would have enough of a material basis to begin sending families from Scotland. The invited families would be each given a house and about 100 acres of land already cleared, but notably these families wouldn't be given legal ownership of the farmsteads. Additional terms offered each interested family "twenty cows, one bull, 500 sheep, eight oxen, six horses and a few hogs," in addition a year's supply of foodstuffs.[5] Despite these considerations, the company never received applicants due to a combination of no advertisement campaigns for the deal and successful farmers in Scotland not finding the offered deal worthwhile.

The only successful source of early colonists for the PSAC would come from the Red River colony. In November 1839 Sir George Simpson instructed Duncan Finlayson to begin promoting the PSAC to colonists.[6] If the initial movement of settlers from Red River was successful, company officials wanted at least fifteen families arriving at the Cowlitz Farm annually. While finding many men were reportedly favorable to offered terms, the inability to own the farmland they would till was a contentious issue.[6]

Finding many families unwilling to sign provisions, Finlayson felt pressure to get a number of willing emigrants as previously ordered. Without the approval of Simpson, Pelly or the Committee, he announced that the farmers could be able to purchase the farmlands they would work on around Cowlitz Farm. This new clause came with a major stipulation, as Finlayson later explained to his superiors. The sales would happen only if the Oregon Question was settled with British receiving the northern bank of the Columbia River, rather than a direct continuation of the 49th parallel.[6]

Overland to Fort Vancouver

James Sinclair was appointed by Finlayson to guide the mostly Métis settler families to Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River.[6] In June 1841, the party left Fort Garry with 23 families consisting of 121 people.[7] They followed the Red River north, crossing Lake Winnipeg and traveled in the Saskatchewan River system to Fort Edmonton. From there they were guided by Maskepetoon, a chief of the Wetaskiwin Cree. Maskepetoon would stay with the party until they reached Fort Vancouver, where he sailed home on board the Beaver.

While on a world tour of company assets, Simpson met the party near Red Deer Hill. Writing in his diary, he gave a description of the settler families:

"Each family had two or three carts, together with bands of horses, cattle and dogs. The men and lads traveled in the saddle, while the vehicles, which were covered with awnings against the sun and rain, carried the women and the young children. As they marched in single file their cavalcade extended above a mile long... The emigrants were all healthy and happy; living with the greatest abundance and enjoying the journey with great relish."[7]

Going through Lake Minnewanka, they eventually reached where the Spray and Bow rivers meet. Following the course of the Spray River valley, the intrepid British colonists then trekked along a tributary, Whiteman's Creek. From here they crossed the Great Divide of the Rocky Mountains, by a new route which became known as Whiteman's Pass. From the summit, they traveled southwest down the Cross River to its junction with the Kootenay River. They entered the upper Columbia River basin via Sinclair Pass, near present-day Radium Hot Springs. From there they journeyed south-west down to Lake Pend'Oreille, then on to an old fort known as Spokane House, then to Fort Colvile. When they arrived at Fort Vancouver, they numbered 21 families of 116 people.[6]

Time with PSAC

Despite the far reaching and extensive plans of Simpson and Pelly, the Red River families didn't act as planned. At Fort Vancouver, fourteen families were relocated to Fort Nisqually, while the remaining seven families were sent to Fort Cowlitz.[6] Within two years however, the families at Fort Nisqually had all left in favor of the Willamette Valley. Crucially, these men held accounts with the HBC and most were in varying levels of debt to the company. A delegation of Red River men arrived at Fort Vancouver in November 1845 to notify McLoughlin of their disinterest in paying back the money owed to the HBC. As McLoughlin was in the process of leaving the HBC, he apparently didn't press the matter as it wasn't of "compelling importance" to him, as historian John C. Jackson later stated.[8] Dugald MacTavish tried and failed to collect upon these debts in the following year.

During its initial years the company had occasionally had to purchase wheat from other sources to meet the RAC demands. In 1840 John McLoughlin had to purchase 4,000 bushels of wheat from Alta California to supplement produce made by the PSAC.[9] During the 1840s pastoral and agricultural produce shipped to New Archangel annually consistently was 30,000 lbs of beef and from 40,000 to 80,000 lbs of wheat.[9] Governor Arvid Etholén praised wheat produced by the PSAC as "incomparably cheaper" than produced bought from American merchants and being of "the best quality."[10] Despite the PSAC's initial growth, its principal manager, John McLoughlin didn't hold a favorable view of the venture. In a letter written to Douglas prior to the 1838 London meetings, McLoughlin criticized what eventually became the PSAC:

"I will take this opportunity to state it is my opinion that, though I think individuals who would devote their attention to raising cattle in the Columbia might make a living at it still it is my opinion the Hudson's Bay Company will make nothing by it."[11]

The Oregon Treaty that was negotiated in between Great Britain and the United States and went into effect in July 1846 upon the exchange of ratifications settled the Oregon question.[12] This treaty had specific provisions regarding the Puget Sound Agricultural Company in Article IV, namely that the United States would respect PSAC property but had the right to purchase any of the properties.[12]

In 1863, Great Britain and the United States agreed to arbitrate the disposition of the PSAC properties in US territory.[4] The PSAC was awarded $200,000 in compensation in 1869 for all of its properties south of the Canadian-US border as spelled out in the Oregon Treaty.[4] Meanwhile, the company’s operations had shifted north, including agricultural ventures on Vancouver Island.[13] In 1934 the company ceased to be listed on the stock exchange.[13]

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.