Public Broadcasting Act of 1967

1967 US law establishing the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 (47 U.S.C. § 396) issued the congressional corporate charter for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), a private nonprofit corporation funded by taxpayers to disburse grants to public broadcasters in the United States.[1] The act was supported by many prominent Americans, including Fred Rogers ("Mister Rogers"), NPR founder and creator of All Things Considered Robert Conley, and Senator John O. Pastore of Rhode Island, then chairman of the Senate Subcommittee on Communications, during House and United States Senate hearings in 1967.

An editor has expressed concern that this article may have a number of irrelevant and questionable citations. (May 2012) |

| |

| Long title | An Act to amend the Communications Act of 1934 by extending and improving the provisions thereof relating to grants for construction of educational television broadcasting facilities, by authorizing assistance in the construction of non-commercial educational radio broadcasting facilities, by establishing a nonprofit corporation to assist in establishing innovative educational programs, to facilitate educational program availability, and to aid the operation of educational broadcasting facilities; and to authorize a comprehensive study of instructional television and radio; and for other purposes. |

|---|---|

| Enacted by | the 90th United States Congress |

| Effective | November 7, 1967 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | 90-129 |

| Statutes at Large | 81 Stat. 365 |

| Codification | |

| Titles amended | 47 U.S.C.: Telegraphy |

| U.S.C. sections amended | 47 U.S.C. ch. 5 §§ 390-397, 609 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

The act charged the CPB with encouraging and facilitating program diversity, and expanding and developing non-commercial broadcasting. The CPB would have the funds to help local stations create innovative programs, thereby increasing the service of broadcasting in the public interest throughout the country.[2]

Background

A need of improvement to educational television -- as radio was not initially considered in further improvement of noncommercial broadcasting -- began in 1964 in the Democratic Party Platform with calls for a bolstering of education in general and a line dedicated to the enhancement of educational television throughout the U.S.[3] Public interest in educational television was brought about by the proposals by the Carnegie Commission on Educational Television and the Ford Foundation.[4]

Provisions

Summarize

Perspective

Title I

Title I of the Public Broadcasting Act details the costs of upgrading educational broadcasting, both for radio and television, as well as establishes how much of the money budgeted to educational broadcasting can be granted to broadcasters in each state and how that granted money is used.[5]

Title II

Title II establishes the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) as a nonprofit corporation tasked with aiding in the creation, development, and funding of noncommercial educational television and radio networks and programming, as well as creating programming for noncommercial educational networks to use and broadcast to the public. Created programs that are controversial should be objective and present a balance of opinions. Likewise, the corporation cannot support any political candidate nor any political party. The CPB was granted $9 million to use during its first year of operation, no more than $250,000 of which was to be granted by the CPB to noncommercial educational stations. The Act also calls for the establishment of a Board of Directors made up of 15 individuals chosen by the president and confirmed by Senate whose duty it is to initially set up the CPB and to continue to facilitate its actions. These directors serve six year terms, two of which may be served consecutively.[5]

Title III

Title III allows and grants money for a study to be done by the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare in order to ascertain how educational broadcasting can be improved further.[5]

Other

Minor amendments were also made to other areas of the Communications Act of 1934 -- previously only containing language pertaining to and directly addressing television -- to include radio broadcasting in its oversight.[5]

Legislative history

Summarize

Perspective

On April 11, 1967, the Senate Subcommittee on Communications held their hearing on the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967. In the proceedings of the hearing, all of the witnesses who appeared voiced their support for the general purposes of the bill, and the majority supported the passage of the legislation as it was currently drafted. The majority of witnesses' testimonies focused on providing the legislators with information about how the CPB should operate in regards to specific topics related to the witnesses' fields of expertise, but not necessarily ideas or suggestions that warranted the addition, removal, or editing of any of the bill's provisions. Some voiced concern over the government involvement in the operations of the would-be Corporation for Public Broadcasting, worrying that the provisions of the bill that established the apolitical nature of the corporation were not strong enough. Several other witnesses whose backgrounds were in the commercial broadcasting industry urged the committee to authorize the immediate use of satellite technology by the CPB.[6]

The debate of the bill on the Senate floor was mostly in favor of the passage of the bill as passed by committee with a few amendments which aligned with the original intent of the bill; however, the same was not the case in the House. On the House floor during debate, an amendment proposed by Samuel L. Devine would have removed Title II, the establishment of the CPB, from the bill but divide $5 million equally amongst all noncommercial broadcasting stations. The amendment was defeated by a roll-call vote of 167-194. A similar amendment proposed by Albert Watson simply deleted Title II and was likewise rejected with a teller vote of 111-120. Both rejected bill-killing amendments were supported by a coalition of Southern Democrats and Republicans.[7]

The act was originally to be called the "Public Television Act" and focus exclusively on television, worrying supporters of public radio. However, in a sudden change of fortune, Senator Robert Griffin of Michigan suggested changing the name to the "Public Broadcasting Act" when the bill passed through the Senate. This set the path for the incorporation of National Public Radio (NPR) in 1970.[8] After several revisions, including last-minute changes added with Scotch Tape, The United States House of Representatives passed the bill 266-91 on September 21, 1967, with 51 members voting "present" and two not voting.

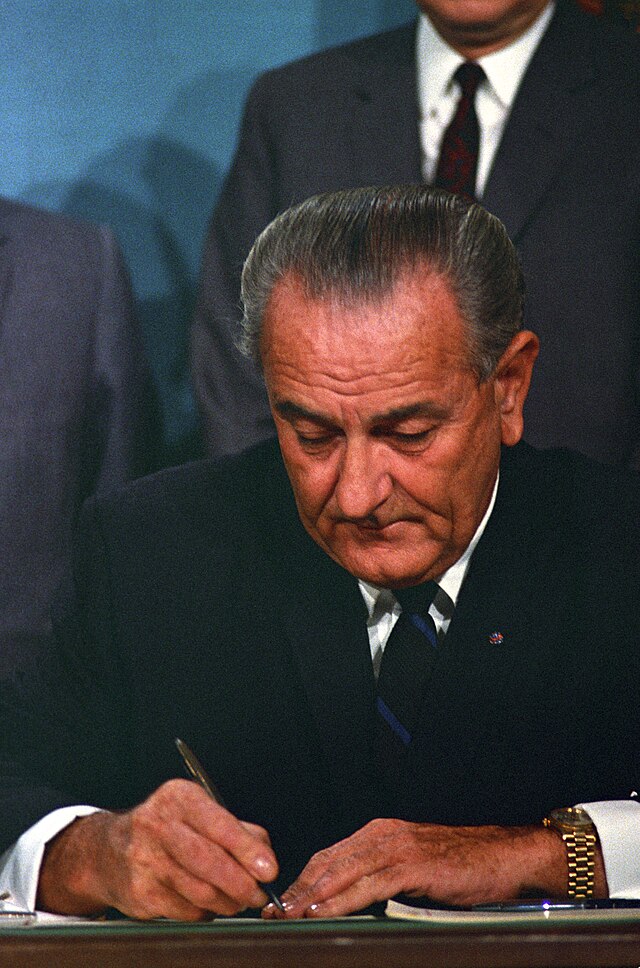

When President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the act into law on November 7, 1967, he described its purpose as:

It announces to the world that our nation wants more than just material wealth; our nation wants more than a 'chicken in every pot.' We in America have an appetite for excellence, too. While we work every day to produce new goods and to create new wealth, we want most of all to enrich man's spirit. That is the purpose of this act.[9]

It will give a wider and, I think, stronger voice to educational radio and television by providing new funds for broadcast facilities. It will launch a major study of television's use in the Nation's classrooms and its potential use throughout the world. Finally — and most important — it builds a new institution: the Corporation for Public Broadcasting."[9]

Most political observers viewed the Act as a component of Johnson's "Great Society" initiatives intended to increase governmental support for health, welfare, and educational activities in the U.S. The support that the Act and similar legislation addressing other matters received reflected the liberal consensus of the period.

Educational television

Summarize

Perspective

In addition to the progress made by the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967, other areas such as educational television (ETV) made headway as well. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) had reserved almost 250 channel frequencies for educational stations in 1953,[10] although, seven years later, only 44 such stations were in operation.[11] However, by 1969, the number of stations had climbed to 175.

Each week, the National Education Television and Radio Center (renamed National Educational Television in 1963) aired a few hours of relatively inexpensive programs to educational stations across the country. These programs were produced by a plethora of stations across the nation, such as WGBH in Boston, WTTW in Chicago, and KQED in San Francisco. Unfortunately, with the growth of commercial radio and television, the more poorly-funded educational programming was being largely ignored by the American public. The higher budgets of the commercial networks and stations were making it difficult for the educational programs to attract viewers' attention, due to their smaller budgets and, thus, lower production values.

Networks and stations that previously aired a modest amount of educational programming began to eschew it in the early 1960s in favor of a near-total emphasis on commercial entertainment programs because they lured more people, and thus more advertising dollars. Locally-run, nonprofit television and radio tried to "fill in the gaps"[12] but, due to the technological gap created by budget constraints (typically caused by being no more than a line item on a municipality, state, or university's annual budget that could not be adjusted in the middle of a year to address arising needs), it was increasingly difficult to produce programming with high production values that viewers had become accustomed to.

In 1965, the increasing distance between commercial and educational programming and audience size led to the Carnegie Corporation of New York ordering its Commission on Education Television to conduct a study of the American ETV system and, from that study, derive changes and recommendations for future action regarding ETV. The report created from the study was published about two years later and became a "catalyst and model"[11] for the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967.

With the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967, smaller television and radio broadcasters, operated usually by community organizations, state and local governments, or universities, were able to be seen and heard by a wider range of audiences, and new and developing broadcasters were encouraged to display their knowledge to the country. Before 1967, commercial radio and television were mostly used by major networks and local broadcasters in order to attract advertisers and make as large a profit as possible, often with little or no regard to the general welfare of their audiences, except for news broadcasts shown only a few hours per day and public-affairs programs that aired in low-rated timeslots such as Sunday mornings, when a considerable segment of the American public attended religious worship. Smaller stations were unable to make much impact due to their lack of funds for matters such as program production, properly functioning equipment, signal transmission, and promotion in their communities at large.[12] The act provided a window for certain broadcasters to get their messages, sometimes unpopular ones, across and, in some cases, straight to the point, without fear of undue influence exerted by commercial or political interests. Even people who had no access to cable television (at the time of the Act's adoption, a medium used to receive and amplify distant TV signals for clear viewing and not available everywhere in the U.S.; the first cable-only network did not appear until 1972, with HBO) were usually provided with public television as an alternative viewing option to the Big Three television networks of the time; only some larger markets had independent television stations prior to the late 1970s.

Many adults and children today would have grown up without some of the more well-known PBS shows, such as Sesame Street and Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, without this legislation. Some other shows, aimed at adults, provide information to address everyday needs or concerns. To increase funding, stations began offering privileges and merchandise as rewards to induce private household donations; however, these were generally targeted at larger audiences than those who normally watched. This became a source of controversy among some in the industry in later years, particularly beginning in the 1970s with reductions in Federal funding that occurred because of political and economic changes from the days of the Act's 1967 inception.

Concepts

Public broadcasting includes multiple media outlets, which receive some or all of their funding from the public. The main media outlets consist of radio and television. Public broadcasting consists of organizations such as CPB, Public Broadcasting Service, and National Public Radio, organizations independent of each other and of the local public television and radio stations across the country.[13]

CPB was created and funded by the federal government; it does not produce or distribute any programming.[14]

PBS is a private, nonprofit corporation, founded in 1969, whose members are America's public TV stations — noncommercial, educational licensees that operate nearly 360 PBS member stations and serve all 50 states, Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam and American Samoa.[15][failed verification] The nonprofit organization also reaches almost 117 million people through television and nearly 20 million people online each month.[15][failed verification]

NPR is a multimedia news organization and radio program producer, with member stations and supporters nationwide.[16]

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.