Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Pteranodon

Genus of pterosaur of the Late Cretaceous From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Pteranodon (/təˈrænədɒn/; from Ancient Greek: πτερόν, romanized: pteron 'wing' and ἀνόδων, anodon 'toothless')[2][3] is a genus of pterosaur that included some of the largest known flying reptiles, with P. longiceps having a wingspan of over 6 m (20 ft). They lived during the late Cretaceous geological period of North America in present-day Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, South Dakota and Alabama.[4] More fossil specimens of Pteranodon have been found than any other pterosaur, with about 1,200 specimens known to science, many of them well preserved with nearly complete skulls and articulated skeletons. It was an important part of the animal community in the Western Interior Seaway.

When the first fossils of Pteranodon were found, they were assigned to toothed pterosaur genera, such as Ornithocheirus and Pterodactylus. In 1876, Othniel Charles Marsh recognised it as a genus of its own, making particular note of its complete lack of teeth, which at the time was unique among pterosaurs. Over the decades, multiple species would be assigned to Pteranodon, though today, only two are recognised: P. longiceps, the type species, and P. sternbergi. A third species, P. maiseyi, may also exist. Some researchers have suggested the latter two as a genus of their own, Geosternbergia, though this is the subject of some debate. Another genus split from Pteranodon, Dawndraco, may be synonymous with Geosternbergia if that genus is valid, or with Pteranodon if it is not.

Pteranodon is part of the family Pteranodontidae, part of the clade Pteranodontia, which also includes nyctosaurids. Pteranodontians form a larger clade, Pteranodontoidea, alongside ornithocheiromorphs, and that clade falls under the suborder Pterodactyloidea. While not dinosaurs, pterosaurs such as Pteranodon form a clade closely related to dinosaurs as both fall within the clade Avemetatarsalia.

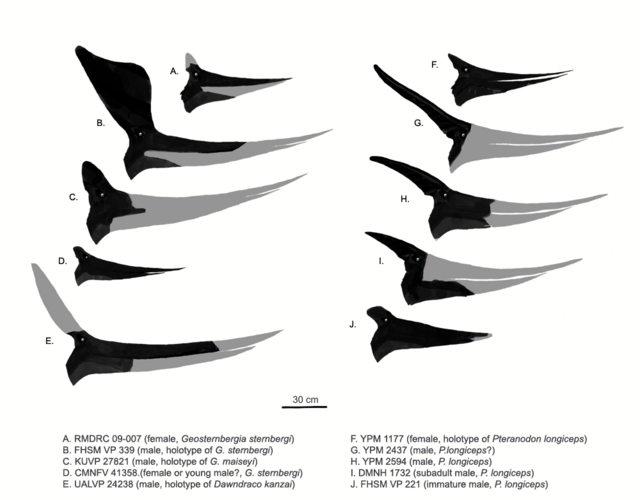

Male and female Pteranodon differed in size and crest shape. Males attained wingspans of 5.6–7.6 m (18–25 ft); females were smaller, averaging 3.8 m (12 ft). The crests of males were far larger than those of females. In P. longiceps, they were long and backswept, whereas in P. sternbergi, they were tall and upright. Females also had wider pelvises than males.

Remove ads

Discovery and history

Summarize

Perspective

First fossils

Pteranodon was the first pterosaur found outside of Europe. Its fossils first were found by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1871,[5] in the Late Cretaceous Smoky Hill Chalk deposits of western Kansas. These chalk beds were deposited at the bottom of what was once the Western Interior Seaway, a large shallow sea over what now is the midsection of the North American continent. These first specimens, YPM 1160 and YPM 1161, consisted of partial wing bones, as well as a tooth from the prehistoric fish Xiphactinus, which Marsh mistakenly believed to belong to this new pterosaur (all known pterosaurs up to that point had teeth). In 1871, Marsh named the find Pterodactylus oweni, assigning it to the well-known (but much smaller) European genus Pterodactylus. Marsh also collected more wing bones of the large pterosaur in 1871. Realizing that the name he had chosen had already been used for Harry Seeley's European pterosaur species Pterodactylus oweni in 1864, Marsh renamed his giant North American pterosaur Pterodactylus occidentalis, meaning "Western wing finger," in his 1872 description of the new specimen. He named two additional species, based on size differences: Pterodactylus ingens (the largest specimen so far), and Pterodactylus velox (the smallest).[6]

Meanwhile, Marsh's rival Edward Drinker Cope had unearthed several specimens of the large North American pterosaur. Based on these specimens, Cope named two new species, Ornithochirus umbrosus and Ornithochirus harpyia, in an attempt to assign them to the large European genus Ornithocheirus, though he misspelled the name (forgetting the 'e').[6] Cope's paper naming his species was published in 1872, just five days after Marsh's paper. This resulted in a dispute, fought in the published literature, over whose names had priority in what obviously were the same species.[6] Cope conceded in 1875 that Marsh's names did have priority over his, but maintained that Pterodactylus umbrosus was a distinct species (but not genus) from any that Marsh had named previously.[7] Re-evaluation by later scientists has supported Marsh's case, refuting Cope's assertion that P. umbrosus represented a larger, distinct species.[6]

A toothless pterosaur

While the first Pteranodon wing bones were collected by Marsh and Cope in the early 1870s, the first Pteranodon skull was found on May 2, 1876, along the Smoky Hill River in Wallace County (now Logan County), Kansas, USA, by Samuel Wendell Williston, a fossil collector working for Marsh.[8] A second, smaller skull soon was discovered as well. These skulls showed that the North American pterosaurs were different from any European species, in that they lacked teeth and had bony crests on their skulls. Marsh recognized this major difference, describing the specimens as "distinguished from all previously known genera of the order Pterosauria by the entire absence of teeth." Marsh recognized that this characteristic warranted a new genus, and he coined the name Pteranodon ("wing without tooth") in 1876. Marsh reclassified all the previously named North American species from Pterodactylus to Pteranodon. He considered the smaller skull to belong to Pteranodon occidentalis, based on its size. Marsh classified the larger skull, YPM 1117, in the new species Pteranodon longiceps, which he thought to be a medium-sized species in between the small P. occidentalis and the large P. ingens.[9][6] Marsh also named several additional species: Pteranodon comptus and Pteranodon nanus were named for fragmentary skeletons of small individuals, while Pteranodon gracilis was based on a wing bone that he mistook for a pelvic bone. He soon realized his mistake, and re-classified that specimen again into a separate genus, which he named Nyctosaurus. P. nanus was also later recognized as a Nyctosaurus specimen.[10][6]

In 1892, Samuel Williston examined the question of Pteranodon classification. He noticed that, in 1871, Seeley had mentioned the existence of a partial set of toothless pterosaur jaws from the Cambridge Greensand of England, which he named Ornithostoma. Because the primary characteristic Marsh had used to separate Pteranodon from other pterosaurs was its lack of teeth, Williston concluded that "Ornithostoma" must be considered the senior synonym of Pteranodon. However, in 1901, Pleininger pointed out that "Ornithostoma" had never been scientifically described or even assigned a species name until Williston's work, and therefore had been a nomen nudum and could not beat out Pteranodon for naming priority. Williston accepted this conclusion and went back to calling the genus Pteranodon.[6] However, both Williston and Pleininger were incorrect, because unnoticed by both of them was the fact that, in 1891, Seeley himself had finally described and properly named Ornithostoma, assigning it to the species O. sedgwicki. In the 2010s, more research on the identity of Ornithostoma showed that it was probably not Pteranodon or even a close relative, but may in fact have been an azhdarchoid, a different type of toothless pterosaur.[11]

Revising species

Williston was also the first scientist to critically evaluate all of the Pteranodon species classified by Cope and Marsh. He agreed with most of Marsh's classification, with a few exceptions. First, he did not believe that P. ingens and P. umbrosus could be considered synonyms, which even Cope had come to believe. He considered both P. velox and P. longiceps to be dubious; the first was based on non-diagnostic fragments, and the second, though known from a complete skull, probably belonged to one of the other, previously-named species. In 1903, Williston revisited the question of Pteranodon classification, and revised his earlier conclusion that there were seven species down to just three. He considered both P. comptus and P. nanus to be specimens of Nyctosaurus, and divided the others into small (P. velox), medium (P. occidentalis), and large species (P. ingens), based primarily on the shape of their upper arm bones. He thought P. longiceps, the only one known from a skull, could be a synonym of either P. velox or P. occidentalis, based on its size.[6]

In 1910, Eaton became the first scientist to publish a more detailed description of the entire Pteranodon skeleton, as it was known at the time. He used his findings to revise the classification of the genus once again based on a better understanding of the differences in pteranodont anatomy. Eaton conducted experiments using clay models of bones to help determine the effects of crushing and flattening on the shapes of the arm bones Williston had used in his own classification. Eaton found that most of the differences in bone shapes could be easily explained by the pressures of fossilization, and concluded that no Pteranodon skeletons had any significant differences from each other besides their size. Therefore, Eaton was left to decide his classification scheme based on differences in the skulls alone, which he assigned to species just as Marsh did, by their size. In the end, Eaton recognized only three valid species: P. occidentalis, P. ingens, and P. longiceps.[6]

The discovery of specimens with upright crests, classified by Harksen in 1966 as the new species Pteranodon sternbergi, complicated the situation even further. prompting another revision of the genus by Halsey W. Miller in 1972. Because it was impossible to determine crest shape for all of the species based on headless skeletons, Miller concluded that all Pteranodon species except the two based on skulls (P. longiceps and P. sternbergi) must be considered nomena dubia and abandoned. The skull Eaton thought belonged to P. ingens was placed in the new species Pteranodon marshi, and the skull Eaton assigned to P. occidentalis was re-named Pteranodon eatoni. Miller also recognized another species based on a skull with a crest similar to that of P. sternbergi; Miller named this Pteranodon walkeri. To help bring order to this tangle of names, Miller created three subgenera. P. marshi and P. longiceps were placed in the subgenus Longicepia,[12] though this was later changed to simply Pteranodon due to the rules of priority.[13] P. sternbergi and P. walkeri, the upright-crested species, were given the subgenus Sternbergia,[12] which was later changed to Geosternbergia because Sternbergia was preoccupied.[14] Finally, Miller named the subgenus Occidentalia for P. eatoni, the skull formerly associated with P. occidentalis. Miller further expanded the concept of Pteranodon to include Nyctosaurus as a fourth subgenus. Miller considered these to be an evolutionary progression, with the primitive Nyctosaurus, at the time thought to be crestless, giving rise to small-crested Occidentalia, which in turn gave rise to long-crested Pteranodon, finally leading to tall-crested Geosternbergia.[12] However, Miller made several mistakes in his study concerning which specimens Marsh had assigned to which species, and most scientists disregarded his work on the subject in their later research.[6] In 1984, Robert Milton Schoch published another revision that essentially returned to Marsh's original classification scheme, most notably sinking P. longiceps as a synonym of P. ingens.[15]

Recognizing variation

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, S. Christopher Bennett published several major papers reviewing the anatomy, taxonomy and life history of Pteranodon.[16] In 1992, he published a paper discussing sexual dimorphism and its role in individual variation among Pteranodon fossils, a follow-up of a 1987 paper he authored on the same subject.[17] In the 1992 paper, he referred only to two species, P. longiceps and P. sternbergi.[18] Two years later, he published a paper fully revising its taxonomy, wherein he concluded that only P. longiceps and P. sternbergi were valid species. P. marshi and P. walkeri were regarded as junior synonyms of P. longiceps, and P. eatoni as a junior synonym of P. stenbergi. The remainder were either rendered nomina dubia or placed in Nyctosaurus.[6]

Remove ads

Description

Summarize

Perspective

Body size and sexual dimorphism

Adult male Pteranodon were among the largest pterosaurs, and were the largest flying animals known until the late 20th century, when the giant azhdarchid pterosaurs were discovered. The wingspan of an average adult male Pteranodon was 5.6 m (18 ft). Adult females were much smaller, averaging 3.8 m (12 ft) in wingspan.[19] A large specimen of Pteranodon longiceps, USNM 50130, is estimated to have a wingspan of 6.25–6.5 m (20.5–21.3 ft), body length of 2.6 m (8.5 ft) and body mass of 50 kg (110 lb).[19][20][21][22] Even larger specimens had wingspans of 7.25–7.6 m (23.8–24.9 ft).[19][23] Size aside, females were distinguished by their short, rounded head crests and wide pelvic canals, whereas males had narrow hips and very large head crests, likely serving a display function.[17][18]

Methods used to estimate the mass of large male Pteranodon specimens (those with wingspans of about 7 meters) have been notoriously unreliable, producing a wide range of estimates. In a review of pterosaur size estimates published in 2010, Mark Witton and Michael Habib argued that the largest estimate of 93 kg (205 lb) is much too high and an upper limit of 20–35 kg (44–77 lb) is more realistic. Witton and Habib considered the methods used by researchers who obtained smaller mass estimates equally flawed. Most have been produced by scaling modern animals such as bats and birds up to Pteranodon size, despite the fact that pterosaurs have vastly different body proportions and soft tissue anatomy from any living animal.[24]

Skull and beak

Unlike earlier pterosaurs, such as Rhamphorhynchus and Pterodactylus, Pteranodon had toothless beaks, similar to those of birds. Pteranodon beaks were made of solid, bony margins that projected from the base of the jaws. The beaks were long, slender, and ended in thin, sharp points. The upper jaw, which was longer than the lower jaw, was curved upward; while this normally has been attributed only to the upward-curving beak, one specimen (UALVP 24238) has a curvature corresponding with the beak widening towards the tip. While the tip of the beak is not known in this specimen, the level of curvature suggests it would have been extremely long. The unique form of the beak in this specimen led Alexander Kellner to assign it to a distinct genus, Dawndraco, in 2010.[16]

The most distinctive characteristic of Pteranodon is its cranial crest. These crests consisted of skull bones (frontals) projecting upward and backward from the skull. The size and shape of these crests varied due to a number of factors, including age, sex, and species. Male Pteranodon sternbergi, the older species of the two described to date, had a more vertical crest with a broad forward projection, while their descendants, Pteranodon longiceps, evolved a narrower, more backward-projecting crest.[8] Females of both species were smaller and bore small, rounded crests.[6] The crests were probably mainly display structures, though they may have had other functions as well.[18]

Postcranial skeleton

The neural spines of Pteranodon's vertebrae were narrow.[25] Like many pterosaurs and birds, it possessed a notarium, a fused mass comprising the first six dorsal vertebrae.[26] Similarly, the first few ribs were fused.[16] The pelvic bones were fused to the synsacrum, a mass of vertebrae that included at least two dorsal vertebrae,[18] the sacral vertebrae, and the first caudal vertebra.[16] The sacrals were strengthened by bony ligaments. Beyond the synsacrum, the tail was relatively short, and the last few vertebrae were fused into a bony rod. The entire length of the tail was about 3.5% as long as the wingspan, or up to 25 cm (9.8 in) in the largest males.[25]

Pteranodon's scapulae were oriented in such a way that each one braces the other, due to their fusion with the coracoids, providing increased integrity during flight.[27] The humeri were extremely robust, with large, curved deltopectoral crests. The radius and ulna were similarly robust.[28] The first three metacarpals were very slender,[27] and their respective digits sported short, curved unguals (claws).[28][27] Pteranodon's hind feet had four metatarsals, which were tipped with less curved claws.[27]

Remove ads

Paleobiology

Summarize

Perspective

Flight

The wing shape of Pteranodon suggests that it would have flown rather like a modern-day albatross. This is based on the fact that Pteranodon had a high aspect ratio (wingspan to chord length) similar to that of the albatross — 9:1 for Pteranodon, compared to 8:1 for an albatross. Albatrosses spend long stretches of time at sea fishing, and use a flight pattern called "dynamic soaring" which exploits the vertical gradient of wind speed near the ocean surface to travel long distances without flapping, and without the aid of thermals (which do not occur over the open ocean the same way they do over land).[29] While most of a Pteranodon flight would have depended on soaring, like long-winged seabirds, it probably required an occasional active, rapid burst of flapping, and studies of Pteranodon wing loading (the strength of the wings vs. the weight of the body) indicate that they were capable of substantial flapping flight, contrary to some earlier suggestions that they were so big they could only glide.[24] However, a more recent study suggests that it relied on thermal soaring, unlike modern seabirds but much like modern continental flyers and the extinct Pelagornis.[30]

Like other pterosaurs, Pteranodon probably took off from a standing, quadrupedal position. Using their long forelimbs for leverage, they would have vaulted themselves into the air in a rapid leap. Almost all of the energy would have been generated by the forelimbs. The upstroke of the wings would have occurred when the animal cleared the ground followed by a rapid down-stroke to generate additional lift and complete the launch into the air.[24] It is possible that Pteranodon could have achieved this from the water, as well as on land,[31] which has been speculated for various other such as the distantly related Anhanguera.[32][33]

Locomotion

Historically, terrestrial locomotion in Pteranodon, as in pterosaurs overall, has been the subject of debate, chiefly the matter of whether or not they were bipedal or quadrupedal.[34] The earliest model of Pteranodon locomotion, put forward by Cherrie D. Bramwell and G. R. Whitfield, suggested that they were utterly incapable of walking or standing. Instead, they suggested that it moved on land by pushing itself around, and that it took off by perching on cliffsides and allowing the wind to take it.[35] Subsequent works largely revolved around more conventional methods of locomotion, such as bipedalism[20][36] and various kinds of quadrupedalism.[37][38] In 2004, Sankar Chatterjee and R. J. Templin proposed a dual system, wherein pterosaurs walked quadrupedally most of the time, but opted for a bipedal takeoff.[34] The latter, however, is unlikely.[24] Trackways suggest that pterosaurs like Pteranodon were quadrupedal.[39]

Diet

The diet of Pteranodon is known to have included fish;[19][20] fossilized fish bones have been found in the stomach area of one Pteranodon, and a fossilized fish bolus has been found between the jaws of another Pteranodon, specimen AMNH 5098. Numerous other specimens also preserve fragments of fish scales and vertebrae near the torso, indicating that fish made up a majority of the diet of Pteranodon (though they may also have taken invertebrates).[19]

Traditionally, most researchers have suggested that Pteranodon would have taken fish by dipping their beaks into the water while in low, soaring flight. However, this was probably based on the assumption that the animals could not take off from the water surface.[19] It is more likely that Pteranodon could take off from the water, and would have dipped for fish while swimming rather than while flying. Even a small, female Pteranodon could have reached a depth of at least 80 centimeters (31 in) with its long bill and neck while floating on the surface, and they may have reached even greater depths by plunge-diving into the water from the air like some modern long-winged seabirds.[19] In 1994, Bennett noted that the head, neck, and shoulders of Pteranodon were as heavily built as diving birds, and suggested that they could dive by folding back their wings like the modern gannet.[19]

Crest function

Pteranodon was notable for its skull crest, though the function of this crest has been a subject of debate. Most explanations have focused on the blade-like, backward pointed crest of male P. longiceps, however, and ignored the wide range of variation across age and sex. The fact that the crests vary so much rules out most practical functions other than for use in mating displays.[40] Therefore, display was probably the main function of the crest, and any other functions were secondary.[18]

Scientific interpretations of the crest's function began in 1910, when George Francis Eaton proposed two possibilities: an aerodynamic counterbalance and a muscle attachment point. He suggested that the crest might have anchored large, long jaw muscles, but admitted that this function alone could not explain the large size of some crests.[41] Bennett (1992) agreed with Eaton's own assessment that the crest was too large and variable to have been a muscle attachment site.[18] Eaton had suggested that a secondary function of the crest might have been as a counterbalance against the long beak, reducing the need for heavy neck muscles to control the orientation of the head.[41] Wind tunnel tests showed that the crest did function as an effective counterbalance to a degree, but Bennett noted that, again, the hypothesis focuses only on the long crests of male P. longiceps, not on the larger crests of P. sternbergi and very small crests that existed among the females. Bennett found that the crests of females had no counterbalancing effect, and that the crests of male P. sternbergi would, by themselves, have a negative effect on the balance of the head. In fact, side to side movement of the crests would have required more, not less, neck musculature to control balance.[18]

In 1943, Dominik von Kripp suggested that the crest may have served as a rudder, an idea embraced by several later researchers.[18][42] One researcher, Ross S. Stein, even suggested that the crest may have supported a membrane of skin connecting the backward-pointing crest to the neck and back, increasing its surface area and effectiveness as a rudder.[43] The rudder hypothesis, again, does not take into account females nor P. sternbergi, which had an upward-pointing, not backward-pointing crest. Bennett also found that, even in its capacity as a rudder, the crest would not provide nearly so much directional force as simply maneuvering the wings. The suggestion that the crest was an air brake, and that the animals would turn their heads to the side in order to slow down, suffers from a similar problem.[44] Additionally, the rudder and air brake hypotheses do not explain why such large variation exists in crest size even among adults.[18]

Alexander Kellner suggested that the large crests of the pterosaur Tapejara, as well as other species, might be used for heat exchange, allowing these pterosaurs to absorb or shed heat and regulate body temperature, which also would account for the correlation between crest size and body size. There is no evidence of extra blood vessels in the crest for this purpose, however, and the large, membranous wings filled with blood vessels would have served that purpose much more effectively.[18]

With these hypotheses ruled out, the best-supported hypothesis for crest function seems to be as a sexual display. This is consistent with the size variation seen in fossil specimens, where females and juveniles have small crests and males large, elaborate, variable crests.[18]

Sexual variation

Adult Pteranodon specimens may be divided into two distinct size classes, small and large, with the large size class being about one and a half times larger than the small class, and the small class being twice as common as the large class. Both size classes lived alongside each other, and while researchers had previously suggested that they represent different species, Christopher Bennett showed that the differences between them are consistent with the concept that they represent females and males, and that Pteranodon species were sexually dimorphic. Skulls from the larger size class preserve large, upward and backward pointing crests, while the crests of the smaller size class are small and triangular. Some larger skulls also show evidence of a second crest that extended long and low, toward the tip of the beak, which is not seen in smaller specimens.[18]

The gender of the different size classes was determined, not from the skulls, but from the pelvic bones. Contrary to what may be expected, the smaller size class had disproportionately large and wide-set pelvic bones. Bennett interpreted this as indicating a more spacious birth canal, through which eggs would pass. He concluded that the small size class with small, triangular crests represent females, and the larger, large-crested specimens represent males.[18] The overall size and crest size also corresponds to age. Immature specimens are known from both females and males, and immature males often have small crests similar to adult females. Therefore, it seems that the large crests only developed in males when they reached their large, adult size, making the sex of immature specimens difficult to establish from partial remains.[20]

The fact that females appear to have outnumbered males two to one suggests that, as with modern animals with size-related sexual dimorphism, such as sea lions and other pinnipeds, Pteranodon might have been polygynous, with a few males competing for association with groups consisting of large numbers of females. Similar to modern pinnipeds, Pteranodon may have competed to establish territory on rocky, offshore rookeries, with the largest, and largest-crested, males gaining the most territory and having more success mating with females. The crests of male Pteranodon would not have been used in competition, but rather as "visual dominance-rank symbols", with display rituals taking the place of physical competition with other males. If this hypothesis is correct, it also is likely that male Pteranodon played little to no part in rearing the young; such a behavior is not found in the males of modern polygynous animals who father many offspring at the same time.[18]

Remove ads

Paleoecology

Summarize

Perspective

Specimens assigned to Pteranodon have been found in both the Smoky Hill Chalk deposits of the Niobrara Formation, and the slightly younger Sharon Springs deposits of the Pierre Shale Formation. When Pteranodon was alive, this area was covered by a large inland sea, known as the Western Interior Seaway. Famous for fossils collected since 1870, these formations extend from as far south as Kansas in the United States to Manitoba in Canada. However, Pteranodon specimens (or any pterosaur specimens) have only been found in the southern half of the formation, in Kansas, Wyoming, and South Dakota. Despite the fact that numerous fossils have been found in the contemporary parts of the formation in Canada, no pterosaur specimens have ever been found there. This strongly suggests that the natural geographic range of Pteranodon covered only the southern part of the Niobrara, and that its habitat did not extend farther north than South Dakota.[6]

Some very fragmentary fossils belonging to pteranodontian pterosaurs, and possibly Pteranodon itself, have also been found on the Gulf Coast and East Coast of the United States. For example, some bone fragments from the Mooreville Formation of Alabama and the Merchantville Formation of Delaware may have come from Pteranodon, though they are too incomplete to make a definite identification.[6] Some remains from Japan have also been tentatively attributed to Pteranodon, but their distance from its known Western Interior Seaway habitat makes this identification unlikely.[6]

Pteranodon longiceps would have shared the sky with the giant-crested pterosaur Nyctosaurus. Compared to P. longiceps, which was a very common species, Nyctosaurus was rare, making up only 3% of pterosaur fossils from the formation. Also less common was the early toothed bird, Ichthyornis.[45] Below the surface, the sea was populated primarily by invertebrates such as ammonites and squid. Vertebrate life, apart from basal fish, included sea turtles, such as Toxochelys, the plesiosaurs Elasmosaurus and Styxosaurus, and the flightless diving bird Parahesperornis. Mosasaurs were the most common marine reptiles, with genera including Clidastes, Mosasaurus and Tylosaurus.[8] At least some of these marine reptiles are known to have fed on Pteranodon. Barnum Brown, in 1904, reported plesiosaur stomach contents containing "pterodactyl" bones, most likely from Pteranodon.[46] Fossils from terrestrial dinosaurs also have been found in the Niobrara Chalk, suggesting that animals who died on shore must have been washed out to sea (one specimen of a hadrosaur appears to have been scavenged by a shark).[47]

It is likely that, as in other polygynous animals (in which males compete for association with harems of females), Pteranodon lived primarily on offshore rookeries, where they could nest away from land-based predators and feed far from shore; most Pteranodon fossils are found in locations which at the time, were hundreds of kilometres from the coastline.[18]

Remove ads

Classification

Summarize

Perspective

Timespan and evolution

Pteranodon fossils are known primarily from the Niobrara Formation of the central United States. Broadly defined, Pteranodon existed for more than four million years, during the Santonian stage of the Cretaceous period.[6] The genus is present in most layers of the Niobrara Formation except for the upper two; in 2003, Kenneth Carpenter surveyed the distribution and dating of fossils in this formation, demonstrating that Pteranodon sternbergi existed there from 88 to 85 million years ago, while P. longiceps existed between 86 and 84.5 million years ago. A possible third species, which Kellner named Geosternbergia maiseyi in 2010, is known from the Sharon Springs member of the Pierre Shale Formation in Kansas, Wyoming, and South Dakota, dating to between 81.5 and 80.5 million years ago.[45] Fossils of P. longiceps have been found in layers dating to 80-78.25 million years ago.[48]

In the early 1990s, Bennett noted that the two major morphs of pteranodont present in the Niobrara Formation were precisely separated in time with little, if any, overlap. Due to this, and to their gross overall similarity, he suggested that they probably represent chronospecies within a single evolutionary lineage lasting about 4 million years. In other words, only one species of Pteranodon would have been present at any one time, and P. sternbergi (or Geosternbergia) in all likelihood was the direct ancestor species of P. longiceps.[19]

Valid species

Many researchers consider there to be at least two species of Pteranodon. However, aside from the differences between males and females described above, the post-cranial skeletons of Pteranodon show little to no variation between species or specimens, and the bodies and wings of all pteranodonts were essentially identical.[6]

Two species of Pteranodon are traditionally recognized as valid: Pteranodon longiceps, the type species, and Pteranodon sternbergi. The species differ only in the shape of the crest in adult males (described above), and possibly in the angle of certain skull bones.[6] Because well-preserved Pteranodon skull fossils are extremely rare, researchers use stratigraphy (i.e. which rock layer of the geologic formation a fossil is found in) to determine species identity in most cases.

Pteranodon sternbergi is the only known species of Pteranodon with an upright crest. The lower jaw of P. sternbergi was 1.25 meters (4.1 ft) long.[49] It was collected by George F. Sternberg in 1952 and described by John Christian Harksen in 1966, from the lower portion of the Niobrara Formation. It was older than P. longiceps and is considered by Bennett to be the direct ancestor of the later species.[6]

Because fossils identifiable as P. sternbergi are found exclusively in the lower layers of the Niobrara Formation, and P. longiceps fossils exclusively in the upper layers, a fossil lacking the skull can be identified based on its position in the geologic column (though for many early fossil finds, precise data about its location was not recorded, rendering many fossils unidentifiable).[16]

Below is a cladogram showing the phylogenetic placement of this genus within Pteranodontia from Andres and Myers (2013).[50]

| Pteranodontia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Alternative classifications

Due to the subtle variations between specimens of pteranodontid from the Niobrara Formation, most researchers have assigned all of them to the single genus Pteranodon, in at least two species (P. longiceps and P. sternbergi) distinguished mainly by the shape of the crest. However, the classification of these two forms has varied from researcher to researcher. In 1972, Halsey Wilkinson Miller published a paper arguing that the various forms of Pteranodon were different enough to be placed in distinct subgenera. He named these Pteranodon (Occidentalia) occidentalis (for the now-disused species P. occidentalis) and Pteranodon (Sternbergia) sternbergi. However, the name Sternbergia was preoccupied, and in 1978 Miller re-named the species Pteranodon (Geosternbergia) sternbergi, and named a third subgenus/species combination for P. longiceps, as Pteranodon (Longicepia) longiceps. Most prominent pterosaur researchers of the late 20th century however, including S. Christopher Bennett and Peter Wellnhofer, did not adopt these subgeneric names, and continued to place all pteranodont species into the single genus Pteranodon.

In 2010, pterosaur researcher Alexander Kellner revisited H.W. Miller's classification. Kellner followed Miller's opinion that the differences between the Pteranodon species were great enough to place them into different genera. He placed P. sternbergi into the genus named by Miller, Geosternbergia, along with the Pierre Shale skull specimen which Bennett had previously considered to be a large male P. longiceps. Kellner argued that this specimen's crest, though incompletely preserved, was most similar to Geosternbergia. Because the specimen was millions of years younger than any known Geosternbergia, he assigned it to the new species Geosternbergia maiseyi. Numerous other pteranodont specimens are known from the same formation and time period, and Kellner suggested they may belong to the same species as G. maiseyi, but because they lack skulls, he could not confidently identify them.[16] However, both species previously referred to Geosternbergia were separately included as those of Pteranodon (P. sternbergi and P. maiseyi) based on phylogenetic analysis in 2024.[51]

Disused species

A number of additional species of Pteranodon have been named since the 1870s, although most now are considered to be junior synonyms of two or three valid species. The best-supported is the type species, P. longiceps, based on the well-preserved specimen including the first-known skull found by S. W. Williston. This individual had a wingspan of 7 meters (23 ft).[52] Other valid species include the possibly larger P. sternbergi, with a wingspan originally estimated at 9 m (30 ft).[52] P. oweni (P. occidentalis), P. velox, P. umbrosus, P. harpyia, and P. comptus are considered to be nomina dubia by Bennett (1994) and others who question their validity. All probably are synonymous with the more well-known species.

Because the key distinguishing characteristic Marsh noted for Pteranodon was its lack of teeth, any toothless pterosaur jaw fragment, wherever it was found in the world, tended to be attributed to Pteranodon during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This resulted in a plethora of species and a great deal of confusion. The name became a wastebasket taxon, rather like the dinosaur Megalosaurus, to label any pterosaur remains that could not be distinguished other than by the absence of teeth. Species (often dubious ones now known to be based on sexual variation or juvenile characters) have been reclassified a number of times, and several subgenera have in the 1970s been erected by Halsey Wilkinson Miller to hold them in various combinations, further confusing the taxonomy (subgenera include Longicepia, Occidentalia, and Geosternbergia). Notable authors who have discussed the various aspects of Pteranodon include Bennett, Padian, Unwin, Kellner, and Wellnhofer. Two species, P. oregonensis and P. orientalis, are not pteranodontids and have been renamed Bennettazhia oregonensis and Bogolubovia orientalis respectively.

List of species and synonyms

Status of names listed below follow a survey by Bennett, 1994 unless otherwise noted.[6]

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads