Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions

1977 amendment protocol to the Geneva Convention From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Protocol I (also Additional Protocol I and AP I)[4] is a 1977 amendment protocol to the Geneva Conventions concerning the protection of civilian victims of international war, including "armed conflicts in which peoples are fighting against colonial domination, alien occupation or racist regimes".[5] In practice, Additional Protocol I updated and reaffirmed the international laws of war stipulated in the Geneva Conventions of 1949 to accommodate developments of warfare since the Second World War (1937–1945).

State signatories (3)

Summary of provisions

Summarize

Perspective

Protocol I contains 102 articles. The following is a basic overview of the protocol.[6] In general, the protocol reaffirms the provisions of the original four Geneva Conventions. However, the following additional protections are added.

- Article I states that the convention applies in "armed conflicts in which peoples are fighting against colonial domination and alien occupation and against racist régimes in the exercise of their right of self-determination".

- Article 15 states that civilian medical and religious personnel shall be respected and protected. This includes that Parties shall give all available help to civilian medical personnel.

- Articles 17 and 81 authorize the ICRC, national societies, or other impartial humanitarian organizations to provide assistance to the victims of war.

- Article 35 bans weapons that "cause superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering", as well as means of warfare that "cause widespread, long-term, and severe damage to the natural environment".

- Article 37 prohibits perfidy. It identifies four types of perfidy and differentiates ruses of war from perfidy.

- Article 40 prohibits no quarter, i.e. to order that there shall be no survivors, to threaten as such, or to conduct hostilities on that basis.

- Article 42 outlaws attacks on pilots and aircrews who are parachuting from an aircraft in distress. Once they landed in territory controlled by an adverse party, they must be given an opportunity to surrender before being attacked, unless it is apparent that they are engaging in a hostile act. Airborne troops, whether in distress or not, are not given the protection afforded by this Article and, therefore, may be attacked during their descent.

- Article 43 deals with the identification of Armed Forces that are Party to a conflict, and states that combatants "shall be subject to an internal disciplinary system which, inter alia, shall enforce compliance with the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict."

- Article 47(1) "A mercenary shall not have the right to be a combatant or a prisoner of war."

- Articles 51 and 54 outlaw indiscriminate attacks on civilian populations, and destruction of food sources, water, and other materials needed for survival. This include directly attacking civilian (non-military) targets, but also using technologies whose scope of destruction cannot be limited.[7] A total war that does not distinguish between civilian and military targets is considered a war crime.

- Articles 53 prohibits attacks on historic monuments, works of art or places of worship.

- Article 56 covers attacks on "works and installations containing dangerous forces", such as dams, dykes, nuclear electrical generating stations. These targets (and other military targets in their vicinity) may not be attacked if they threaten the release of dangerous forces.

- Chapter II, consisting of Articles 76, 77 and 78, provides special protections for women and children. In particular, the death penalty shall not be executed on children under eighteen years old, and shall be avoided on pregnant women and mothers having dependent infants. Further, children under fifteen years old shall not be recruited into the armed forces, and Parties shall take all reasonable measures to prevent them from taking part in hostilities.

- Article 79 states that journalists shall be considered as civilians and given the same protections. Civilian war correspondents attached to armed forces who are captured shall have the same rights as prisoners of wars, as outlined in the Third Geneva Convention.[6]

- Article 85(3f) prohibits the perfidious use of the red cross, red crescent or red lion and sun or of other protective signs recognized by the Geneva Conventions.

- Article 90 describes how International Fact-Finding Commissions can be established in situations of serious violations of the Geneva Conventions.

Ratification status

Summarize

Perspective

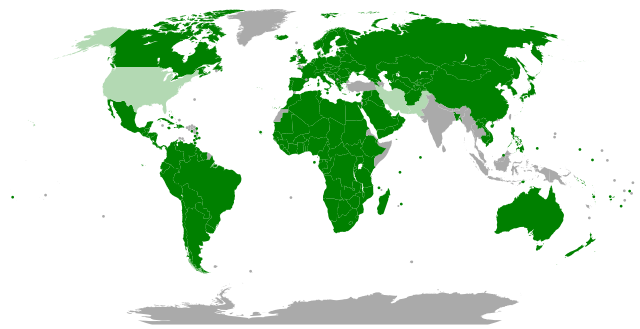

As of August 2024, it had been ratified by 174 states.[8] The United States, Iran, and Pakistan signed it on 12 December 1977 but never ratified it. Israel, India, and Turkey have not signed the treaty.

Israel

Protocols I and II to the Geneva Conventions are not ratified by Israel. According to legal scholar and human rights attorney Noura Erakat, this allows the Israeli government to recognize the Israeli-Palestinian conflict ''neither as a civil war ('non-international armed conflict,' NIAC) nor a war against a liberation movement ('international armed conflict,' IAC).''[9] This way, force used by Palestinian factions can be deemed illegal and illegitimate.[9]

Russia

On 16 October 2019, President Vladimir Putin signed an executive order[10] and submitted a State Duma bill to revoke the statement accompanying Russia's ratification of the Protocol I, accepting the competence of the Article 90(2) International Fact-Finding Commission.[11][12][13] The bill was supplied with the following warning:[11][13]

Exceptional circumstances affect the interests of the Russian Federation and require urgent action. ... In the current international environment, the risks of abuse of the commission's powers for political purposes by unscrupulous states who act in bad faith have increased significantly.

Article 1(4)

Summarize

Perspective

Article 1(4) says:

The situations referred to in the preceding paragraph include armed conflicts in which peoples are fighting against colonial domination and alien occupation and against racist regimes in the exercise of their right of self-determination.

Jan Arno Hessbruegge, who works at the New York Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, examined the three categories listed in his book Human Rights and Personal Self-defense in International Law:[14]

- "colonial domination" refers to far-away overseas colonies with clear geographical boundaries. It was not meant to apply to states conquering and annexing adjacent territories.

- "alien occupation" refers to "cases where the occupied territory did not yet form part of a state at the time of occupation but was occupied by a distinct group, such as the Palestinian people".

- "racist regimes" included countries that had institutionalized racism, not countries where the government merely practices racial discrimination. At the time the protocol was written, this mainly referred to South Africa and Rhodesia.

Legal scholar Waldemar A. Solf opined that Article 1(4) was largely symbolic and gave party states "a plausible basis for denying its application to their situation", while the states which the article most applied to (e.g., Israel, and apartheid-era South Africa) would not sign the agreement at all.[15]

The Reagan administration declared that Article 1(4) would "grant terrorists a psychological and legal victory",[16] as it appears to grant combatant status to non-state actors, many of which (such as the Palestine Liberation Organization) have been designated as terrorist groups by the United States and other countries. By contrast, an article in the International Review of the Red Cross argues that this article, in fact, strengthens the fight against terrorism, by applying the laws of war (including all its prohibitions and obligations) to national wars of liberation. By granting combatant status to non-state actors in wars of liberation, it too requires non-state actors to follow the strict prohibitions against acts of terror (Article 13, Article 51(2), etc.).[17]

See also

- Command responsibility

- Geneva Conventions

- List of parties to the Geneva Conventions

- First Geneva Convention on the treatment of battlefield casualties in the field

- Jus in bello

- Targeted killing

- Protocol II, a 1977 amendment adopted relating to the protection of victims of non-international armed conflicts

- Protocol III, a 2005 amendment adopted specifying the adoption of the Red Crystal emblem

- United Nations Mercenary Convention

Notes

- Russia revoked their ratification of the point 2 of Article 90 on 16 October 2019 via executive order and submitted such legislation to be adopted by the State Duma.[3]

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.