Proceratosaurus

Extinct genus of dinosaurs From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Proceratosaurus (/proʊ̯sɛrətoʊˈsɔːrəs/) is a genus of theropod dinosaur that lived during the Middle Jurassic in what is now England. The holotype and only known specimen consists of a mostly complete skull with lower jaws and a hyoid bone, found near Minchinhampton, a town in Gloucestershire. It was originally described as a species of Megalosaurus in 1910, M. bradleyi, but this species was moved to its own genus, Proceratosaurus, in 1926. The genus was named for the perceived resemblance of its incomplete cranial crest to that of Ceratosaurus, and supposed relation to that dinosaur.

| Proceratosaurus Temporal range: Bathonian, | |

|---|---|

| |

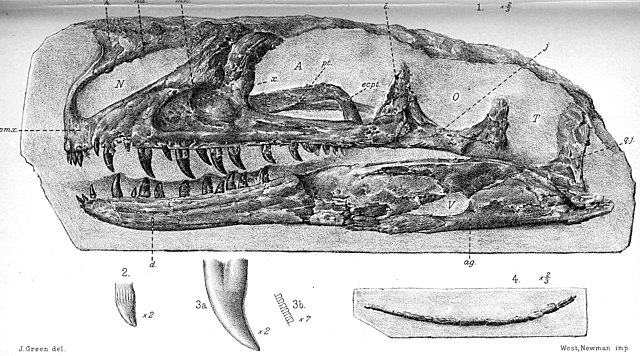

| Holotype skull (NHMUK PV R 4860) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Superfamily: | †Tyrannosauroidea |

| Family: | †Proceratosauridae |

| Genus: | †Proceratosaurus von Huene, 1926 |

| Species: | †P. bradleyi |

| Binomial name | |

| †Proceratosaurus bradleyi | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

A small dinosaur, the skull of Proceratosaurus is 26.9 cm (10.6 in) long as preserved, and the dinosaur is estimated to have measured around 3 m (9.8 ft) in length. The skull is characterised by features such as large external naris (bony nostril), a cranial crest that begins at the junction between the premaxilla and the nasal bone, and the skull is very pneumatic. The teeth are unusual in being heterodont, having different sizes depending on their positions in the jaw. Proceratosaurus is considered a coelurosaur, specifically a member of the family Proceratosauridae, and is among the earliest known members of both Coelurosauria and Tyrannosauroidea, with its complete crest probably being larger than that of Ceratosaurus and more similar to its close relative Guanlong.

Proceratosaurus likely had a diet consisting of relatively small prey such as primitive mammals and small herbivorous dinosaurs. The crest was probably used for display. The dinosaur is known from the Great Oolite Group of England, having been found in either the White Limestone Formation or the Forest Marble Formation. During the Bathonian age when Proceratosaurus lived, Britain along with the rest of Western Europe formed a subtropical island archipelago, with southern Britain having a seasonally dry climate. Other dinosaurs known from the Bathonian of Britain include the large theropod Megalosaurus, the large sauropod Cetiosaurus, as well as indeterminate stegosaurs, ankylosaurs and heterodontosaurids.

History of discovery

Summarize

Perspective

In 1910, the palaeontologist Arthur Smith Woodward reported a partial skull of a theropod dinosaur, discovered some time prior by F. Lewis Bradley during excavation for a reservoir in the vicinity of Minchinhampton, a town in the Cotswolds in Gloucestershire, South West England. Bradley had prepared the skull so that the left side was exposed, and submitted it to the Geological Society of London. Woodward made the skull the holotype specimen of a new species of the genus Megalosaurus, naming it M. bradleyi in honour of its discoverer.[1][2] Megalosaurus, the first named non-bird dinosaur, described in 1824 also based on English fossils,[3] was historically used for any fragmentary remains of large theropods from around the world (wastebasket taxon).[4]

At the time it was discovered, M. bradleyi was one of the most complete theropod skulls known from Europe, possibly with the exception of the crushed and hard to interpret skulls of Compsognathus and Archaeopteryx. Since 1942, the skull has been housed at the Natural History Museum, where it is catalogued as specimen NHMUK PV R 4860. The upper part of the skull is missing due to a fissure that had eroded the rock and was partially filled with calcite. While overall well preserved, the skull is somewhat compressed from side-to side compared to what it would have been in life.[2][5]

In 1923, the palaeontologist Friedrich von Huene moved the species to the new genus Proceratosaurus, assuming it was the ancestor of the North American genus Ceratosaurus, but since the name was only used in a schematic it has been considered a nomen nudum, an invalidly published name. He validated the name three years later in two 1926 articles by providing a diagnosis (pointing out distinguishing features) of the genus. While remaining one of the best preserved theropod skulls in Europe, and globally one of the best preserved Middle Jurassic theropod skulls, it since received little scientific attention, mainly being mentioned in studies about general aspects of theropod anatomy and evolution. The holotype skull was since CT scanned at the University of Texas, further mechanically prepared to reveal additional details of the skull, jaw, and teeth, and re-described by the palaeontologist Oliver Rauhut and colleagues in 2010.[2][6]

Description

Summarize

Perspective

The only known skull of Proceratosaurus is 26.9 cm (10.6 in) long as preserved. The 2010 redescription estimated a total body length of 2.98–3.16 m (9.8–10.4 ft) and a body mass of 28–36 kg (62–79 lb).[2] Other sources gave estimates of 3–4 m (9.8–13.1 ft) in length and 50–100 kg (110–220 lb) in body mass.[7][8] Well preserved fossils of the related tyrannosauroids Yutyrannus and Dilong indicate that they were covered in relatively simple feathers in life, similar to the down feathers of modern birds.[9]

When complete, the skull of Proceratosaurus appears to have been relatively long but not particularly deep, being more than three times longer than high. The external naris (the bony nostril opening) makes up around 20% of the skull length, being around 7 cm (2.8 in) long. The antorbital fenestra (the large opening in front of the eye) is roughly triangular in shape, with a maximum length of 6.9–7.1 cm (2.7–2.8 in), and this fenestra is also surrounded by a large fossa (depression) extending onto the surrounding skull bones. The partially preserved orbit (eye socket) has an "inverted egg-shape" and is marginally taller than long, at maximum 6 cm (2.4 in) and around 5.55 cm (2.19 in), respectively. The infratemporal fenestra is narrow and elongate, being around 5.4 cm (2.1 in) tall and kidney-shaped, and slightly constricted at its midpoint.[2]

The premaxilla (the frontmost bone of the upper jaw) is relatively small, forming a rounded end to the snout. The nasal bones, as well as the contacting upper back edge of the premaxillae to their front, bear the partially preserved base of a crest, which when complete, like other proceratosaurids, likely formed a large pneumatic (air-filled) crest that ran across the midline of the skull, which may have been covered by keratin.[2][9][10] The shape of the complete crest is unknown and was previously thought to be similar to that of Ceratosaurus, but after the discovery of the close, crested relative Guanlong, that genus has since been considered a likely model.[1][2][11]

The mandible of Proceratosaurus is 26 cm (10 in) long, somewhat shorter than the skull, which is unusual for theropods. The retroarticular process at the posterior end of the mandible where the lower jaw articulates with the skull is relatively short. The dentary bone (the tooth-bearing front portion of the mandible) is slender, though it becomes considerably wider towards the rear, which bears a large, elongate mandibular fenestra (opening). The dentary bone tapers to a blunt point towards the front. Although not all teeth are preserved, the tooth sockets show that each premaxilla had around 4 teeth, each maxilla had around 22 teeth, and each dentary had around 20 teeth.[2] The teeth are heterodont, showing differences in morphology depending on their position in the jaw. The premaxillary teeth are D-shaped in cross-section, with the front facing surface of the teeth being arched.[9] The maxillary teeth, like those of many other theropods, are ziphodont, that is they are laterally (side-to-side) compressed and serrated.[2]

The preserved left hyoid bone of Proceratosaurus is around 12 cm (4.7 in) long along its curved length. The central part of the shaft is relatively straight, while the posterior and front ends are flexed upwards.[2]

Classification

Summarize

Perspective

Woodward classified Proceratosaurus as a species of Megalosaurus in his 1910 description, because both had four premaxillary teeth.[1] Later study during the 1930s by von Huene suggested a closer relationship with Ceratosaurus, and he thought both dinosaurs represented members of the group Coelurosauria.[12]

It was not until the late 1980s, after Ceratosaurus had been shown to be a much more basal theropod and not a coelurosaur, that the classification of Proceratosaurus was re-examined. The palaeontologist Gregory S. Paul suggested that it was a close relative of Ornitholestes, again mainly because of the crest on the nose (though the idea that Ornitholestes bore a nasal crest was later disproved).[13] Paul considered both Proceratosaurus and Ornitholestes to be neither ceratosaurs nor coelurosaurs, but instead primitive allosauroids. Furthermore, Paul considered the much larger theropod species Piveteausaurus divesensis to belong to the genus Proceratosaurus, coining the new combination Proceratosaurus divesensis.[14] However, no overlapping bones between the two had yet been exposed from the rock around their fossils, and future study showed that they were indeed distinct.[2]

A 1998 phylogenetic analysis by Thomas R. Holtz Jr. found Proceratosaurus to be a basal coelurosaur.[15] Several subsequent studies confirmed this, finding Proceratosaurus and Ornitholestes only distantly related to ceratosaurids and allosauroids, though one opinion published in 2000 considered Proceratosaurus a ceratosaurid without presenting supporting evidence. A 2004 study by Holtz also placed Proceratosaurus among the coelurosaurs, though with only weak support, and again found an (also weakly supported) close relationship with Ornitholestes.[2]

The first major re-evaluation of Proceratosaurus and its relationships was published in 2010 by Oliver Rauhut and colleagues. Their study concluded that Proceratosaurus was in fact a coelurosaur, and moreover a tyrannosauroid, a member of the lineage leading to the giant tyrannosaurs of the Late Cretaceous. Furthermore, they found that Proceratosaurus was most closely related to the tyrannosauroid Guanlong from China. They named the clade containing these two dinosaurs Proceratosauridae, defined as all theropods closer to Proceratosaurus than to Tyrannosaurus, Allosaurus, Compsognathus, Coelurus, Ornithomimus, or Deinonychus.[2][5]

Subsequent published analyses have consistently recovered Proceratosaurus in a close relationship with Guanlong, as well as the genera Kileskus and Sinotyrannus. Other genera which may be close relatives include Yutyrannus, Dilong, and Stokesosaurus, but the exact affinities of these taxa as they relate to Proceratosaurus remain uncertain.[16][17] Below is a cladogram from a 2022 study by Darren Naish and Andrea Cau on the genus Eotyrannus, which recovered similar relationships to previous studies.[18]

Palaeobiology

Summarize

Perspective

The study of the general biology of Proceratosaurus is somewhat limited by the lack of any post-cranial remains. However, the better-understood anatomy of the related Guanlong allows for general inferences about the biology of Proceratosauridae as a whole. Proceratosaurids were small-bodied animals, in sharp contrast to the tyrannosauroids of the Late Cretaceous. In spite of this, they possessed many of the key adaptations which would come to define the large tyrannosaurids of later periods. In particular, proceratosaurids already possessed the fused nasal bones that were inherited by their successors. In later forms, the fusion of the left and right nasal bones is believed to have been an adaptation for withstanding higher bite forces. Proceratosaurus also possessed the characteristic "D-shaped" premaxillary teeth that are unique to tyrannosauroids. According to Rauhut and colleagues in 2010, this suite of adaptations indicates that the "puncture-pull" feeding strategy of derived tyrannosaurids was already present in proceratosaurids.[2]

A 2023 study by the palaeontologist Evan Johnson-Ransom and colleagues used data from the skulls of Proceratosaurus and Guanlong to create a virtual composite model of a hypothetical, complete proceratosaurid skull. They added muscles to these model skulls to estimate the highest possible bite force. Their model for Proceratosaurus exhibited an estimated bite force of 390 newtons (88 pounds-force), comparable to Dilong or a juvenile Tarbosaurus. These results confirmed the hypothesis that proceratosaurids and other early-diverging tyrannosauroids had a proportionately lower ability to withstand stresses than their derived tyrannosaurid cousins. This is believed to have implications for the dietary ecology and behaviour of proceratosaurids. This lower proportional force distribution would have precluded proceratosaurids from attacking large prey, and therefore they most likely fed on small-bodied prey such as small ornithischians and primitive mammals.[11]

Proceratosaurus and its relatives possessed highly pneumatised skull bones. Cranial sinus tissue excavated the maxillae, jugals, and lacrimal bones, and the jugals themselves were very rugose, which suggests that the area was heavily irrigated by blood vessels.[2] The jugal bone is generally not part of the cranial musculature of most dinosaurs, and the palaeontologist Xu Xing suggested in 2016 that they may have been an important display area for many groups of dinosaur, including proceratosaurids.[19] According to Rauhut and colleagues, the prominent head crest of Proceratosaurus was also likely to have been used as a display feature.[2] Paul agreed in a 2016 popular book, pointing out that the crest would have been too delicate for head-butting.[8]

Palaeoenvironment

Summarize

Perspective

The only known Proceratosaurus specimen was found in the Great Oolite Group in strata dating to the Late Bathonian age of the Middle Jurassic.[2] During the Middle Jurassic, Britain was located in the subtropics,[20] and along with the rest of Western Europe formed a part of an island archipelago, in a seaway narrowly separated from Laurentia (landmass consisting of North America and Greenland) to the west and the Fennoscandian Shield to the northeast.[21] Britain was divided into a number of islands separated by shallow seas,[21] including one formed by the London–Brabant Massif to the east, the Welsh Massif to the west,[22] the Cornubian Massif to the southwest, and the Pennine-Scottish Massif to the north.[23] The coastlines of these islands fluctuated throughout the period, with areas of shallow marine deposition being sometimes transformed temporarily into lagoonal or terrestrial environments with lakes and ponds,[22] and it is suggested that animals were freely able to disperse between them, as well as possibly with the Fennoscandian Shield.[21] The exact locality where Proceratosaurus was discovered has been suggested to correspond to the rocks of the White Limestone Formation,[24] although some authors have suggested this locality is part of the overlying Forest Marble Formation.[25]

The flora from the Bathonian aged Taynton Limestone Formation in Oxfordshire to the east was dominated by araucarian and cheirolepidiacean conifers, the probable conifer Pelourdea, as well as bennettitaleans, with other plants including cycads (Ctenis), ferns (Phlebopteris, Coniopteris), Caytoniales, the living genus Ginkgo, and the seed ferns Pachypteris and Komlopteris, representing a probably seasonally dry coastal environment.[26] The existence of a seasonally-arid climate during the Bathonian period in Britain is corroborated by geological evidence of natural fires among the fossilised vegetation of the White Limestone Formation, which implies the periodic occurrence of long drought episodes.[22] The manner of deposition was primarily by slow-moving bodies of water in a coastal or near-coastal alluvial or lagoonal setting, which was periodically interrupted by high-energy events like floods, which are reflected in the geological record of several localities.[23]

Contemporary fauna

A diverse marine assemblage is known from the Great Oolite Group, including invertebrates, such as bivalves, brachiopods, and echinoderms, as well as vertebrates such as sharks, chimaeras, and ray-finned fish.[22] Large terrestrial vertebrate remains have also been found in the Great Oolite Group. Other British dinosaurs known from the Bathonian period in Britain include the large theropod Megalosaurus[3] and the sauropod Cetiosaurus.[27] Ornithischian remains have also been discovered, but none of these remains have been given scientific names. Bones and teeth of stegosaurs, as well as teeth of ankylosaurs, basal thyreophorans, and heterodontosaurids have been found, alongside remains that have not been confidently assigned to a single group.[28][22] Maniraptoran theropods, possibly including dromaeosaurs, were also present in the environment, also only known from indeterminate teeth.[29] Pterosaurs from the Great Oolite Group included rhamphorhynchids such as the genus Klobiodon, as well as indeterminate probable monofenestratans.[30] Large rhamphorhynchoids like Dearc and monofenestratans like Ceoptera are also known from other Bathonian aged localities in the British Isles.[31] Crocodyliformes were also present in the environment, including atoposaurids and goniopholids.[32]

The Great Oolite Group is also host to one of the most diverse assemblages of primitive mammal fossils of the entire Jurassic Period. This locality, the Kirtlington Mammal Bed, preserves remains from large animals as well, but the majority of fossils known are from mammals and their close relatives. Tritylodontid cynodonts, morganucodonts, docodonts, allotherians, haramiyidans, shuotheriids, eutriconodonts, and early-diverging cladotherians are known from the Kirtlington Bed.[33] Remains of salamanders, frogs, albanerpetontids, turtles, lizards, choristoderes, and sphenodontians have also been discovered in the Kirtilngton mammal bed.[33] Analogous assemblages of vertebrate microfossils have also been found at other localities of similar age,[22] including the Kilmaluag Formation on the Isle of Skye, Scotland, considerably further to the north, whose microvertebrate assemblage shares numerous species with the Kirtlington Fauna, though more completely preserved.[32]

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.