Popular Electronics

American magazine (1954–1982, 1989–1999, in print) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Popular Electronics was an American magazine published by John August Media, LLC, and hosted at TechnicaCuriosa.com. The magazine was started by Ziff-Davis Publishing Company in October 1954 for electronics hobbyists and experimenters. It soon became the "World's Largest-Selling Electronics Magazine". In April 1957, Ziff-Davis reported an average net paid circulation of 240,151 copies.[1] Popular Electronics was published until October 1982 when, in November 1982, Ziff-Davis launched a successor magazine, Computers & Electronics. During its last year of publication by Ziff-Davis, Popular Electronics reported an average monthly circulation of 409,344 copies.[2] The title was sold to Gernsback Publications, and their Hands-On Electronics magazine was renamed to Popular Electronics in February 1989, and published until December 1999. The Popular Electronics trademark was then acquired by John August Media, who revived the magazine, the digital edition of which is hosted at TechnicaCuriosa.com,[3] along with sister titles, Mechanix Illustrated and Popular Astronomy.

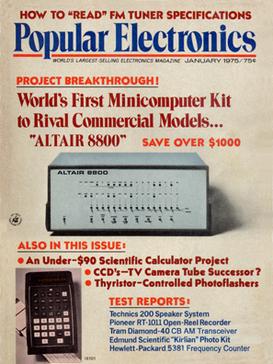

The Altair 8800 computer kit (January 1975) | |

| Categories | hobbyist |

|---|---|

| Frequency | monthly |

| Format | 8.5 x 11in., color |

| Publisher | Ziff Davis Gernsback Publications |

| Total circulation (1982) | 409,344 |

| First issue | October 1954 |

A cover story on Popular Electronics could launch a new product or company. The most famous issue, January 1975, had the Altair 8800 computer on the cover and ignited the home computer revolution. Paul Allen showed that issue to Bill Gates. They wrote a BASIC interpreter for the Altair computer and started Microsoft.[4]

How it started

Summarize

Perspective

Radio & Television News was a magazine for professionals and the editors wanted to create a magazine for hobbyists. Ziff-Davis had started Popular Aviation in 1927 and Popular Photography in 1934 but found that Gernsback Publications had the trademark on Popular Electronics. It was used in Radio-Craft[5] from 1943 until 1948. Ziff-Davis bought the trademark and started Popular Electronics with the October 1954 issue.

Many of the editors and authors worked for both Ziff-Davis magazines. Initially Oliver Read was the editor of both Radio & Television News and Popular Electronics. Read was promoted to Publisher in June 1956.[6] Oliver Perry Ferrell took over as editor of Popular Electronics and William A. Stocklin became editor of Radio & Television News. In Radio & TV News John T. Frye wrote a column on a fictional repair shop where the proprietor, Mac, would interact with other technicians and customers. The reader would learn repair techniques for servicing radios and TVs. In Popular Electronics his column was about two high school boys, Carl and Jerry. Each month the boys would have an adventure that would teach the reader about electronics.

By 1954 building audio and radio kits was a growing pastime. Heathkit and many others offered kits that included all of the parts with detailed instructions. The premier cover shows the assembly of a Heathkit A-7B audio amplifier. Popular Electronics would offer projects that were built from scratch; that is, the individual parts were purchased at a local electronics store or by mail order. The early issues often showed these as father and son projects.

Most of the early projects used vacuum tubes, as transistors (which had just become available to hobbyists) were expensive: the small-signal Raytheon CK722 transistor was US$3.50 in the December 1954 issue, while a typical small-signal vacuum tube (the 12AX7) was $0.61. Lou Garner wrote the feature story for the first issue, a battery-powered tube radio that could be used on a bicycle. Later he was given a column called Transistor Topics (June 1956). Transistors soon cost less than a dollar and transistor projects became common in every issue of Popular Electronics. The column was renamed to Solid State in 1965 and ran under his byline until December 1978.

Typical 1962 issue

Summarize

Perspective

The July 1962 issue had 112 pages, the editor was Oliver P. Ferrell and the monthly circulation was 400,000. The magazine had a full page of electronics news that was called "POP'tronics News Scope." In January 2000 a successor magazine was renamed Poptronics. In the 1960s, Fawcett Publications had a competing magazine, Electronics Illustrated.

The cover showed a 15-inch (38 cm) black and white TV kit by Conar that cost $135. The feature construction story was a "Radiation Fallout Monitor" for "keeping track of the radiation level in your neighborhood." (The Cuban Missile Crisis happened that October.) Other construction projects included "The Fish Finder", an underwater temperature probe; the "Transistorized Tremolo" for an electric guitar; and a one tube VHF receiver to listen to aircraft.

There were regular columns for Citizens Band (CB), amateur radio and shortwave listening (SWL). These would show a reader with his radio equipment each month. (Almost all of the readers were male.)[7] Lou Garner's Transistor Topics covers the new transistorized FM stereo receivers and several readers' circuits. John T. Frye's fictional characters, Carl and Jerry,[8] use a PH meter to locate the source of pollution in a river.

Authors and kits

Summarize

Perspective

As Editor, Olivier Ferrell built a stable of authors who contributed interesting construction projects. These projects established the style of Popular Electronics for years to come. Two of the most prolific authors were Daniel Meyer and Don Lancaster.

Daniel Meyer graduated from Southwest Texas State (1957) and became an engineer at Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas. He soon started writing hobbyist articles. The first was in Electronics World (May 1960) and latter he had a 2 part cover feature for Radio-Electronics (October, November 1962). The March 1963 issue of Popular Electronics featured his ultrasonic listening device on the cover.[9]

Don Lancaster graduated from Lafayette College (1961) and Arizona State University (1966). A 1960s fad was to have colored lights synchronized with music. This psychedelic lighting was made economical by the development of the silicon controlled rectifier (SCR). Don's first published article was "Solid-State 3-Channel Color Organ" in the April 1963 issue of Electronics World. He was paid $150 for the story.[10]

The projects in Popular Electronics changed from vacuum tube to solid state in the early 1960s. Tube circuits used a metal chassis with sockets, transistor circuits worked best on a printed circuit board. They would often contain components that were not available at the local electronics parts store.

Dan Meyer saw the business opportunity in providing circuit boards and parts for the Popular Electronics projects. In January 1964 he left Southwest Research Institute to start an electronics kit company. He continued to write articles and ran the mail order kit business from his home in San Antonio, Texas. By 1965 he was providing the kits for other authors such as Lou Garner. In 1967 he sold a kit for Don Lancaster's "IC-67 Metal Locator". In early 1967 Meyer moved his growing business from his home to a new building on a 3-acre (12,000 m2) site in San Antonio. The Daniel E. Meyer Company (DEMCO) became Southwest Technical Products Corporation (SWTPC) that fall.

In 1967, Popular Electronics had 6 articles by Dan Meyer and 4 by Don Lancaster. Seven of that year's cover stories featured kits sold by SWTPC. In the years 1966 to 1971 SWTPC's authors wrote 64 articles and had 25 cover stories in Popular Electronics. (Don Lancaster alone had 23 articles and 10 were cover stories.) The San Antonio Express-News did a feature story on Southwest Technical Products in November 1972. "Meyer built his mail-order business from scratch to more than $1 million in sales in six years." The company was shipping 100 kits a day from 1800 square feet (1,700 m2) of buildings.[11]

Others noticed SWTPC success. Forrest Mims, a founder of MITS (Altair 8800), tells about his "Light-Emitting Diodes" cover story (Popular Electronics, November 1970) in an interview with Creative Computing.[12]

In March, I sold my first article to Popular Electronics magazine, a feature about light-emitting diodes. At one of our midnight meetings I suggested that we emulate Southwest Technical Products and develop a project article for Popular Electronics. The article would give us free advertising for the kit version of the project, and the magazine would even pay us for the privilege of printing it!

The November 1970 issue also has an article by Forrest M. Mims and Henry E. Roberts titled "Assemble an LED Communicator - The Opticon."[13] A kit of parts could be ordered from MITS in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Popular Electronics paid $400 for the article.

Merger with Electronics World

Summarize

Perspective

Radio & Television News became Electronics World in 1959 and in January 1972 was merged into Popular Electronics. The process started in the summer of 1971 with a new editor, Milton S. Snitzer, replacing the longtime editor, Oliver P. Ferrell. The publishers decided to focus on topics with prosperous advertisers, such as CB Radio and audio equipment. Construction projects were no longer the feature articles. They were replaced by new product reviews.[14] The change in editorial direction upset many authors. Dan Meyer wrote a letter in his SWTPC catalog referring to the magazine, Popular Electronics with Electronics World, as "PEEW". He urged his customers to switch to Radio-Electronics.

Don Lancaster, Daniel Meyer, Forrest Mims, Ed Roberts, John Simonton and other authors switched to Radio-Electronics. Even Solid State columnist Lou Garner moved to Radio-Electronics for a year.[15] Les Solomon, the Popular Electronics Technical Editor, wrote 6 articles in the rival Radio-Electronics using the pseudonym "B. R. Rogen".[14] In 1972 and 1973 some of the best projects appeared in Radio-Electronics as the new Popular Electronics digested the merger. The upcoming personal computer benefited from this competition between Radio-Electronics and Popular Electronics.

In September 1973 Radio-Electronics published Don Lancaster's TV Typewriter, a low cost video display. In July 1974 Radio-Electronics published the Mark-8 Personal Minicomputer based on the Intel 8008 processor.[16] The publishers noted the success of Radio-Electronics and Arthur P. Salsberg took over as Editor in 1974. Salsberg and Technical Editor, Leslie Solomon, brought back the featured construction projects. Popular Electronics needed a computer project so they selected Ed Roberts' Altair 8800[17] computer based on the improved Intel 8080 processor. The January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics had the Altair computer on the cover and this launched the home computer revolution. (However, Walter Isaacson's biography of Steve Jobs incorrectly identified the magazine that ran the article as Popular Mechanics.)

The magazine was digest size (6.5 in × 9 in) for the first 20 years. The cover logo was a sans-serif typeface in a rectangular box. The covers featured a large image of the feature story, usually a construction project. In September 1970 the cover logo was changed to an underlined serif typeface. The magazine's content, typography and layout were also updated.[18] In January 1972 the cover logo added a second line, "including Electronics World", and the volume number was restarted at 1. This second line was used for two years. The large photo of the feature project was gone, replaced by a textual list of articles. In August 1974 the magazine switched to a larger letter size format (8.5 in × 11 in). This was done to allow larger illustrations such as schematics, to switch printing to offset presses, and respond to advertisers desire for larger ad pages.[19] The longtime tag line, "World's Largest Selling Electronics Magazine", was moved from the Table of Contents page to the cover.

Personal computers

Summarize

Perspective

There is debate about what machine was the first personal computer, the Altair 8800 (1975), the Mark-8 (1974), or even back to Kenbak-1 (1971). The computer in the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics captured the attention of the 400,000 or so readers. Before then, home computers were lucky to sell a hundred units. The Altair sold thousands in the first year. By the end of 1975 there were a dozen companies producing computer kits and peripherals using the Altair circuit bus, later renamed the S-100 bus and set as an IEEE standard.

The February 1975 issue featured an "All Solid-State TV Camera"[20] by three Stanford University students: Terry Walker, Harry Garland and Roger Melen. While the Cyclops Camera, as it was called, was designed to use an oscilloscope for the image display, the article mentions that it could also be connected to the Altair computer. It soon was, the authors got one of the first Altair computers and designed an interface for the camera. They also designed a full color video display for the Altair, "The TV Dazzler",[21] that appeared on the cover of the February 1976 issue. This was the start of Cromemco, a computer company that grew to over 500 employees by 1983.[22]

The internet did not exist in 1975 but time-sharing computers did. With a computer terminal and a modem a user could dial into a large multi-user computer. Lee Felsenstein wanted make low-cost versions of modems and terminals available to the hobbyist. The March 1976 issue had the "Pennywhistle Modem"[23] and the July 1976 issue had the "SOL Intelligent Terminal".[24] The SOL, built by Processor Technology, was really an Altair compatible computer and became one of the most successful personal computers at that time.

Popular Electronics had many other computer projects such as the Altair 680, the Speechlab voice recognition board[25] and the COSMAC ELF. They did not have the field to themselves. A dedicated computer magazine, Byte, was started in September 1975. It was soon followed by other new magazines. By the end of 1977, fully assembled computers such as Apple II, Radio Shack TRS-80, and the Commodore PET were on the market. Building computer kits was soon replaced by plugging in assembled boards.

In 1982, Popular Electronics helped to introduce personal computer programming with its Programmer’s Notebook column written by Jim Keogh . Each column focused on a game programming. The column continued onto Computer & Electronics Magazine.[26]

Computers & Electronics

Summarize

Perspective

Popular Electronics continued with a full range of construction projects using the newest technologies such as microprocessors and other programmable devices. In November 1982 the magazine became Computers & Electronics. There were more equipment reviews and fewer construction projects. One of the last major projects was a bidirectional analog-to-digital converter for the Apple II computer published in July and August 1983. Art Salsberg left at the end of 1983 and Seth R. Alpert became editor. The magazine dropped all project articles and just reviewed hardware and software. The circulation was almost 600,000 in January 1985 when Forrest Mims wrote about the tenth anniversary of the Altair 8800 computer.

In October 1984 Art Salsberg started a competing magazine, Modern Electronics. Editor Alexander W. Burawa and contributors Forrest Mims, Len Feldman, and Glenn Hauser moved to Modern Electronics. Here is how Art Salsberg described the new magazine.[27]

Directed to enthusiasts like yourselves, who savor learning more about the latest developments in electronics and computer hardware, Modern Electronics shows you what's new in the world of electronics/computers, how this equipment works, how to use them, and construction plans for useful electronic devices.

Many of you probably know of me from my decade-long stewardship of Popular Electronics magazine, which changed its name and editorial philosophy last year to distance itself from active electronics enthusiasts who move fluidly across electronics and computer product areas. In a sense, then, Modern Electronics is the successor to the original concept of Popular Electronics …

The last issue of Computers & Electronics was April 1985. The magazine still had 600,000 readers but the intense competition from other computer magazines resulted in flat advertising revenues.[28]

Ziff-Davis asset sale

In 1953, William B. Ziff, Jr. (age 23) was thrust into the publishing business when his father died of a heart attack. In 1982, Ziff was diagnosed with prostate cancer so he asked his three sons (ages 14 to 20) if they wanted to run a publishing empire. They did not. Ziff wanted to simplify the estate by selling some of the magazines. In November 1984, CBS bought the consumer group for $362.5 million and Rupert Murdoch bought the business group for $350 million.

This left Ziff-Davis with the computer group and the database publisher (Information Access Company.) These groups were not profitable. Ziff took time off to successfully battle the prostate cancer. (He lived until 2006.) When he returned he focused on magazines like PC Magazine and MacUser to rebuild Ziff-Davis.[29] In 1994 he and his sons sold Ziff-Davis for $1.4 billion.

Gernsback Publications

The title Popular Electronics was sold to Gernsback Publications and their Hands-On Electronics magazine was renamed to Popular Electronics in February 1989. This version was published until it was merged with Electronics Now to become Poptronics in January 2000. In late 2002, Gernsback Publications went out of business and the January 2003 Poptronics was the last issue.[30]

See also

- WGU-20 - an unusual radio station first explained by Popular Electronics

- Nuts and Volts - an electronic hobbyists' magazine still in print

- Elektor - another electronic hobbyists' magazine still in print

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.