Philip Barton Key II

American lawyer (1818–1859) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Philip Barton Key II (April 5, 1818 – February 27, 1859)[1] was an American lawyer who served as U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia.[2] He is most famous for his public affair with Teresa Bagioli Sickles, and his eventual murder at the hands of her husband, Congressman Daniel Sickles of New York. Sickles defended himself by adopting a defense of temporary insanity, the first time the defense had been successfully used in the United States.[2][3]

Philip Barton Key II | |

|---|---|

Harper's Weekly engraving of Philip Barton Key from a photograph by Mathew Brady | |

| 8th United States Attorney for the District of Columbia | |

| In office September 6, 1853 – February 27, 1859 | |

| President | |

| Preceded by | Philip Richard Fendall II |

| Succeeded by | Robert Ould |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 5, 1818 Georgetown, Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Died | February 27, 1859 (aged 40) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Oak Hill Cemetery Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Spouse | Ellen Swan |

| Children | 4 |

| Parents |

|

| Occupation | Lawyer |

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Born in Georgetown, D.C., Key was the son of Francis Scott Key[4][5] and the great-nephew of Philip Barton Key. He was also a nephew of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney.[4][5] He married Ellen Swan, the daughter of a Baltimore attorney, on November 18, 1845.[1] Allegedly the most handsome man in Washington[6] and by 1859 a widower with four children, Key was known to be flirtatious with many women.[7][a]

Key was appointed to his father's former position, United States Attorney for the District of Columbia, by President Pierce in September 1853,[8] during a recess of the Senate;[9] the Senate later confirmed his nomination in March 1854.[10] Four years later, he was nominated,[11] and confirmed again,[12] for another four-year term; thus, he would serve until his death.

Sometime in the spring of 1858, Teresa Sickles began an affair with Key.[2] Dan Sickles, though a serial adulterer himself, had accused his much-younger wife of adultery several times during their five-year marriage, and she had repeatedly denied it to his satisfaction.[4] But then Sickles received a poison pen letter[13] informing him of his wife's affair with Key.[14][2][4] He confronted his wife, who confessed to the affair.[2] Sickles then made his wife write out her confession on paper.[15]

Death

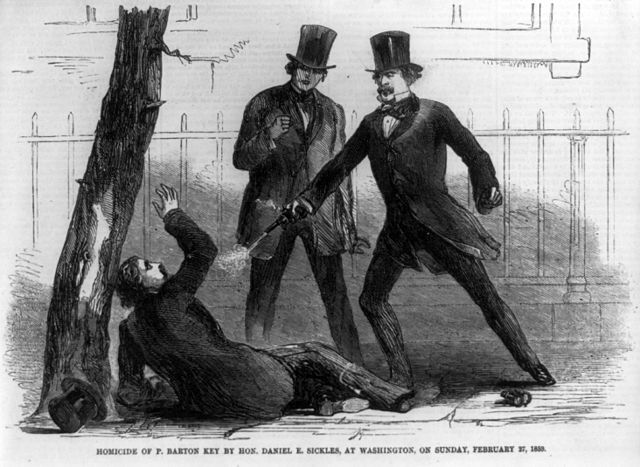

Sickles saw Key sitting on a bench outside the Sickles home on February 27, 1859, signalling to Teresa, and confronted him.[16][2][4][15] Sickles rushed outside into Lafayette Square, cried "Key, you scoundrel, you have dishonored my home; you must die",[17] and with a pistol repeatedly shot the unarmed Key, who was pleading for his life.[2][4] After being shot, an unconscious Key was taken into the nearby Benjamin Ogle Tayloe House, where he died some time later.[18]

Sickles was acquitted based on temporary insanity, a crime of passion, in one of the most controversial trials of the 19th century.[19] It was the first successful use of the defense in the United States.[20] One of Sickles' attorneys, Edwin Stanton, later became the Secretary of War. Newspapers declared Sickles a hero for "saving" women from Key.[20] Years later, while attending the theater in New York City, Sickles became aware of the presence of Key's son, James Key, in the audience; both men watched each other throughout the performance. Nothing else happened.[21]

Key is buried in Oak Hill Cemetery, with a dedicatory in his son-in-law's family plot in Westminster Hall and Burying Ground in Baltimore.[22]

Notes

- Before he married Ellen Swan, Key had been engaged to Virginia Timberlake, a daughter of Peggy Eaton, the center of the Petticoat affair that bedeviled the cabinet of President Andrew Jackson. One of Key's great-granddaughters was the 1960s style icon Pauline de Rothschild.

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.