Peripheral venous catheter

Medical device for administering intravenous therapy From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In medicine, a peripheral venous catheter, peripheral venous line, peripheral venous access catheter, or peripheral intravenous catheter,[1] is a catheter (small, flexible tube) placed into a peripheral vein for venous access to administer intravenous therapy such as medication fluids. This is a common medical procedure.

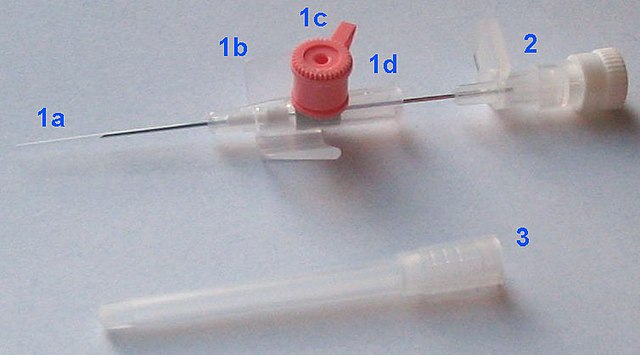

1. The catheter itself is composed of (a) a tip for insertion into the vein, (b) wings for manual handling and securing the catheter with adhesives, (c) a valve to allow injection of drugs with a syringe, (d) an end which allows connection to an intravenous infusion line, and capping in between uses.

2. The needle (partially retracted) which serves only as a guidewire for inserting the cannula.

3. The protection cap which is removed before use.

Medical uses

A peripheral venous catheter is the most commonly used vascular access in medicine. It is given to most emergency department and surgical patients, and before some radiological imaging techniques using radiocontrast, for example.

A peripheral venous catheter is usually placed in a vein on the hand or arm. It should be distinguished from a central venous catheter which is inserted in a central vein (usually in the internal jugular vein of the neck or the subclavian vein of the chest), or an arterial catheter which can be placed in a peripheral or central artery. In children, a topical anaesthetic gel (such as lidocaine) may be applied to the insertion site to facilitate placement.[citation needed]

Blood sampling can be carried out at the time of insertion of a peripheral venous catheter or at a later time.[2]

Peripheral venous catheters may also be used in the emergency treatment of a tension pneumothorax- they can be placed in the second intercostal space along the mid clavicular line in order to relieve tension before definitive management with a chest drain. [3]

Contraindications

It is important to understand when not to place a peripheral venous catheter. Very few contraindications exist. The first absolute contraindication to consider is when the desired therapy can be given via a less invasive route.[4] Site specific absolute contraindications include the presence of an arteriovenous fistula and a planned surgical procedure on an extremity.[4]

Relative contraindications exist but many lack substantial evidence. Peripheral venous catheter placement in a limb with significant sensory or motor injury may increase risk for development of a deep vein thrombosis. In addition, those with a sensory deficit in a limb could have a decreased detection rate of infiltration. Close monitoring of the catheter is recommended if placement in a limb with sensory or motor deficits is required.[4]

Risks and potential complications

Summarize

Perspective

Difficult catheter placement is defined as two or more failed attempts at placement.[5] A history of the patient should be taken to assess for potential risk factors that could suggest a difficult catheter placement. Risk factors include a history of difficult venous catheter placement, obesity, female sex, children, past intravenous drug use and non-visible veins.[5][6] Some medical conditions including diabetes, cancer, and sickle cell disease are also considered risk factors for difficult placement.[6]

Potential complications associated with a peripheral venous catheter include infection, phlebitis, extravasation, infiltration, air embolism, hemorrhage (bleeding) and formation of a hematoma (bruise).[citation needed] A catheter embolism may occur when a small part of the cannula breaks off and flows into the vascular system. When removing a peripheral IV cannula, the tip should be inspected to ensure it's intact.[7]

Because of the risk of insertion-site infection the CDC advises in their guideline that the catheter needs to be replaced every 96 hours.[8] However, the need to replace these catheters routinely is debated.[9] Expert management has been shown to reduce the complications of peripheral lines.[10][11]

It is not clear whether any dressing or securement device is better than the other on reducing the rates of catheter failures.[12]

Technique

Summarize

Perspective

A peripheral venous catheter is introduced into the vein by a needle (similar to blood drawing), which is subsequently removed while the small plastic cannula remains in place. The catheter is then fixed by taping it to the patient's skin or using an adhesive dressing.

Sizes of peripheral venous catheters can be given by Birmingham gauge or French gauge. Diameter is proportional to French gauge and inversely proportional to Birmingham gauge.

Catheter replacement

A Cochrane systematic review of catheter replacement examined that clinically indicated replacement of a catheter vs routine replacement so no clear difference in the rates of various complications listed above. A recent update to this systematic review stated that routine changing of the catheter every 72 to 96 hours still lacks supporting evidence that it should be the standard of care, suggesting that peripheral venous catheters should only be changed when clinically indicated.[14]

History

In the United States, in the 1990s, more than 25 million patients had a peripheral venous line each year.[10]

The insertion of a plastic cannula and withdrawal of the needle was introduced as a technique in 1945.[15] The first disposable version to be marketed was the Angiocath, first sold in 1964. In the 1970s and 1980s, the use of plastic cannulas became routine, and their insertion was more frequently delegated to nursing staff.[16]

Newer catheters have been equipped with additional safety features to avoid needlestick injuries. Modern catheters consist of synthetic polymers such as teflon (hence the often used term 'Venflon' or 'Cathlon' for these venous catheters). In 1950 they consisted of polyvinyl chloride.[17][18] In 1983, the first polyurethane version was introduced.[16]

Additional images

- An arm board is recommended for immobilizing the extremity for cannulation of the hand, the foot or the antecubital fossa in children.[19]

- Just before inserting.

- The catheter in between uses.

- Newer catheter with additional safety features.

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.