Palamism

Theological teachings of Gregory Palamas From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

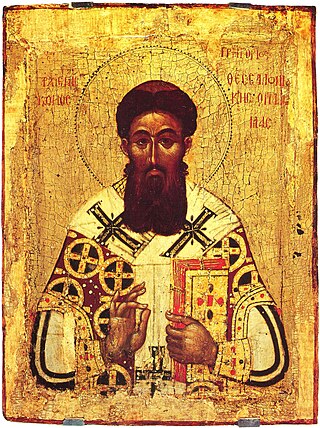

Palamism or the Palamite theology comprises the teachings of Gregory Palamas (c. 1296 – 1359), whose writings defended the Eastern Orthodox practice of Hesychasm against the attack of Barlaam. Followers of Palamas are sometimes referred to as Palamites.

Seeking to defend the assertion that humans can become like God through deification without compromising God's transcendence, Palamas distinguished between God's inaccessible essence and the energies through which he becomes known and enables others to share his divine life.[1] The central idea of the Palamite theology is a distinction between the divine essence and the divine energies[2] that is not a merely conceptual distinction.[3]

Palamism is a central element of Eastern Orthodox theology, being made into dogma in the Eastern Orthodox Church by the Hesychast councils.[4] Palamism has been described as representing "the deepest assimilation of the monastic and dogmatic traditions, combined with a repudiation of the philosophical notion of the exterior wisdom".[5]

Historically, Western Christianity has tended to reject Palamism, especially the essence–energies distinction, sometimes characterizing it as a heretical introduction of an unacceptable division in the Trinity.[6][7] Further, the practices used by the later hesychasts to achieve theosis were characterized as "magic" by the Western Christians.[4] More recently, some Roman Catholic thinkers have taken a positive view of Palamas's teachings, including the essence–energies distinction, arguing that it does not represent an insurmountable theological division between Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.[8]

The rejection of Palamism by the West and by those in the East who favoured union with the West (the "Latinophrones"), actually contributed to its acceptance in the East, according to Martin Jugie, who adds: "Very soon Latinism and Antipalamism, in the minds of many, would come to be seen as one and the same thing".[9]

Background

Summarize

Perspective

Contemplative prayer

An exercise long used among Christians for acquiring contemplation, one "available to everyone, whether he be of the clergy or of any secular occupation",[10] involves focusing the mind by constant repetition of a phrase or word. Saint John Cassian recommended use of the phrase "O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me".[11] Another formula for repetition is the name of Jesus,[12][13] or the Jesus Prayer, which has been called "the mantra of the Orthodox Church",[14] although the term "Jesus Prayer" is not found in the Fathers of the Church.[15] This exercise, which for the early Fathers represented just a training for repose,[16] the later Byzantines developed into a spiritual work of its own, attaching to it technical requirements and various stipulations that became a matter of serious theological controversy[16] (see below), and remain of great interest to Byzantine, Russian and other eastern churches.[16]

Hesychasm

Hesychasm is a form of constant purposeful prayer or experiential prayer, explicitly referred to as contemplation. It is to focus one's mind on God and pray to God unceasingly.

Under church tradition the practice of Hesychasm has it beginnings in the Bible, Matthew 6:6 and the Philokalia. The tradition of contemplation with inner silence or tranquility is shared by all Eastern asceticism having its roots in the Egyptian traditions of monasticism exemplified by such Orthodox monastics as St Anthony of Egypt.

In the early 14th century, Gregory Sinaita learned hesychasm from Arsenius of Crete and spread the doctrine, bringing it to the monks on Mount Athos.[7] The terms Hesychasm and Hesychast were used by the monks on Mount Athos to refer to the practice and to the practitioner of a method of mental ascesis that involves the use of the Jesus Prayer assisted by certain psychophysical techniques. The hesychasts stated that at higher stages of their prayer practice they reached the actual contemplation-union with the Tabor Light, i.e., Uncreated Divine Light or photomos seen by the apostles in the event of the Transfiguration of Christ and Saint Paul while on the road to Damascus.

Development of the doctrine

Summarize

Perspective

As an Athonite monk, Palamas had learned to practice Hesychasm. Although he had written about Hesychasm, it was not until Barlaam attacked it and Palamas as its chief proponent, that Palamas was driven to defend it in a full exposition which became a central component of Eastern Orthodox theology. The debate between the Palamites and Barlaamites continued for over a decade and resulted in a series of synods which culminated finally in 1351 when the Palamite doctrine was canonized as Eastern Orthodox dogma.

Early conflict between Barlaam and Palamas

Around 1330, Barlaam of Seminara came to Constantinople from Calabria in southern Italy, where he had grown up as a member of the Greek-speaking community there. It is disputed whether he was raised as an Orthodox Christian or converted to the Orthodox faith.[17][18] He worked for a time on commentaries on Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite under the patronage of John VI Kantakouzenos. Around 1336, Gregory Palamas received copies of treatises written by Barlaam against the Latins, condemning their insertion of the Filioque into the Nicene Creed. Although this condemnation was solid Eastern Orthodox theology, Palamas took issue with Barlaam's argument in support of it, since Barlaam declared efforts at demonstrating the nature of God (specifically, the nature of the Holy Spirit) should be abandoned, because God is ultimately unknowable and undemonstrable to humans. Thus, Barlaam asserted that it was impossible to determine from whom the Holy Spirit proceeds. According to Sara J. Denning-Bolle, Palamas viewed Barlaam's argument as "dangerously agnostic". In his response titled "Apodictic Treatises", Palamas insisted that it was indeed demonstrable that the Holy Spirit proceeded from the Father but not from the Son.[19] A series of letters ensued between the two but they were unable to resolve their differences amicably. According to J. Konstantinovsky, although both Barlaam and Palamas claimed Dionysius the Areopagite as their authority, their interpretations were radically different. Barlaam cited Dionysius' Mystical Theology to support the argument that God is unspeakable and therefore unknowable. Palamas cited Dionysius as a patristic authority that professed distinctions in God that Barlaam did not acknowledge.[20]

Barlaam's attack on Hesychasm

Steven Runciman reports that, infuriated by Palamas' attacks against him, Barlaam vowed to humiliate Palamas by attacking the Hesychast teaching for which Palamas had become the chief proponent. Barlaam visited Thessalonica, where he made the acquaintance of monks who followed the Hesychast teachings. Runciman describes these monks as ignorant and lacking a real understanding of the Hesychast teaching. Barlaam issued a number of treatises mocking the absurdity of the practices which he reported included, "miraculous separations and reunions of the spirit and the soul, of the traffic which demons have with the soul, of the difference between red lights and white lights, of the entry and departure of the intelligence through the nostrils with the breath, of the shields that gather together round the navel, and finally of the union of Our Lord with the soul, which takes place in the full and sensible certitude of the heart within the navel." Barlaam said that the monks had claimed to see the divine essence with bodily eyes, which he viewed as sheer Messalianism. When asked about the light which they saw, the monks told him that it was neither of the superessential Essence nor an angelic essence nor the Spirit itself, but that the spirit contemplated it as another hypostasis. Barlaam commented snidely, "I must confess that I do not know what this light is. I only know that it does not exist."[21] Barlaam & his supporters portrayed Hesychasm to be a variant of Bogomilism.[22][23]

According to Runciman, Barlaam's attack struck home. He had shown that, in the hands of monks who were inadequately instructed and ignorant of the true Hesychast teaching, the psycho-physical precepts of Hesychasm could produce "dangerous and ridiculous results". To many of the Byzantine intellectuals, Hesychasm appeared "shockingly anti-intellectual". Barlaam nicknamed the Hesychasts "Omphaloscopoi" (the navel-gazers); the nickname has coloured the tone of most subsequent Western writing about the Byzantine mystics. However, Barlaam's triumph was short-lived. Ultimately, the Byzantines had a deep respect for mysticism even if they didn't understand it. And, in Palamas, Barlaam found an opponent who, in Runciman's opinion, was more than his equal in knowledge, intellect and expository skills.[24]

The First Triad

In response to Barlaam's attacks, Palamas wrote nine treatises entitled "Triads For The Defense of Those Who Practice Sacred Quietude". The treatises are called "Triads" because they were organized as three sets of three treatises.

The Triads were written in three stages. The first triad was written in the second half of the 1330s and are based on personal discussions between Palamas and Barlaam although Barlaam is never mentioned by name.[19]

The Hagioritic Tome

Gregory's teaching was affirmed by the superiors and principal monks of Mt. Athos, who met in synod during 1340–1. In early 1341, the monastic communities of Mount Athos wrote the Hagioritic Tome under the supervision and inspiration of Palamas. Although the Tome does not mention Barlaam by name, the work clearly takes aim at Barlaam's views. The Tome provides a systematic presentation of Palamas' teaching and became the fundamental textbook for Byzantine mysticism.[25]

Barlaam also took exception to the doctrine held by the Hesychasts as to the uncreated nature of the light, the experience of which was said to be the goal of Hesychast practice, regarding it as heretical and blasphemous. It was maintained by the Hesychasts to be of divine origin and to be identical to the light which had been manifested to Jesus' disciples on Mount Tabor at the Transfiguration.[26] Barlaam viewed this doctrine of "uncreated light" to be polytheistic because as it postulated two eternal substances, a visible and an invisible God. Barlaam accuses the use of the Jesus Prayer as being a practice of Bogomilism.[27]

The Second Triad

The second triad quotes some of Barlaam's writings directly. In response to this second triad, Barlaam composed the treatise "Against the Messalians" linking the hesychasts to the Messalians and thereby accusing them of heresy. In "Against the Messalians", Barlaam attacked Gregory by name for the first time.[28] Barlaam derisively called the Hesychasts omphalopsychoi (men with their souls in their navels) and accused them of the heresy of Messalianism, also known as Bogomilism in the East.[19][27] According to Meyendorff, Barlaam viewed "any claim of real and conscious experience of God as Messalianism".[29] [30][31]

The Third Triad

In the third Triad, Palamas refuted Barlaam's charge of Messalianism by demonstrating that the Hesychasts did not share the antisacramentalism of the Messalians nor did they claim to physically see the essence of God with their eyes.[29] Meyendorff writes that "Palamas orients his entire polemic against Barlaam the Calabrian on the issue of the Hellenic wisdom which he considers to be the main source of Barlaam's errors."[32]

Role in the Byzantine civil war

Although the civil war between the supporters of John VI Kantakouzenos and the regents for John V Palaeologus was not primarily a religious conflict, the theological dispute between the supporters and opponents of Palamas did play a role in the conflict. Although several significant exceptions leave the issue open to question, in the popular mind (and traditional historiography), the supporters of "Palamism" and of "Kantakouzenism" are usually equated.[33][34] Steven Runciman points out that "while the theological dispute embittered the conflict, the religious and political parties did not coincide."[35] The aristocrats supported Palamas largely due to their conservative and anti-Western tendencies as well as their links to the staunchly Orthodox monasteries.[36] Nonetheless, it was not until the triumph of Kantakouzenos in taking Constantinople in 1347 that the Palamists were able to achieve a lasting victory over the anti-Palamists. When Kantakouzenos was deposed in 1354, the anti-Palamists were not able to again prevail over the Palamists as they had in the past. Martin Jugie attributes this to the fact that, by this time, the patriarchs of Constantinople and the overwhelming majority of the clergy and laity had come to view the cause of Hesychasm as one and the same with that of Orthodoxy.[37]

Hesychast councils at Constantinople

It became clear that the dispute between Barlaam and Palamas was irreconcilable and would require the judgment of an episcopal council. A series of six patriarchal councils, also known as the Hesychast synods, was held in Constantinople on 10 June and August 1341, 4 November 1344, 1 and 8 February 1347 and 28 May 1351 to consider the issues.[38] Collectively, these councils are accepted as having ecumenical status by some Eastern Orthodox Christians,[39] who call them the Fifth Council of Constantinople and the Ninth Ecumenical Council.

The dispute over Hesychasm came before a synod held at Constantinople in May 1341 and presided over by the emperor Andronicus III. The assembly, influenced by the veneration in which the writings of Pseudo-Dionysius were held in the Eastern Church, condemned Barlaam, who recanted.[19] Although Barlaam initially hoped for a second chance to present his case against Palamas, he soon realised the futility of pursuing his cause, and left for Calabria where he converted to the Roman Catholic Church and was appointed Bishop of Gerace.[28]

After Barlaam's departure, Gregory Akindynos became the chief critic of Palamas. A second council held in Constantinople in August 1341 condemned Akindynos and affirmed to findings of the earlier council. Akindynos and his supporters gained a brief victory at the third synod held in 1344, which excommunicated Palamas and one of his disciples, Isidore Buchiras.[4] Palamas and Buchiras recanted.

In 1347, however, their protector, John VI Kantakouzenos, entered Constantinople and forced his opponents to crown him co-emperor. In February 1347, a fourth synod was held which deposed the patriarch, John XIV, and excommunicated Akindynos. Isidore Buchiras, who had been excommunicated by the third synod, was now made patriarch. In the same month, the Barlaamite party held a competing synod which refused to acknowledge Isidore and excommunicated Palamas. Akindynos having died in 1348, Nicephorus Gregoras became the chief opponent of Hesychasm.

Sometime between 1344 and 1350, Palamas wrote the Capita 150 ("One hundred and fifty chapters"). Robert E. Sinkewicz describes this work as an attempt to "recapture the larger vision that had become obscured by the minutiae of the debates." Sinkewicz asserts that "among the polemical works of Palamas, the "Capita 150" is comparable only in importance to "The Triads".[40]

When Isidore I died in 1349, the Hesychasts replaced him by one of their monks, Callistus.

In May 1351, a patriarchal council conclusively exonerated Palamas and condemned his opponents.[28] All those who were unwilling to submit to the orthodox view were to be excommunicated and kept under surveillance at their residences. A series of anathemas were pronounced against Barlaam, Akindynos and their followers; at the same time, a series of acclamations were also declared in favor of Gregory Palamas and the adherents of his doctrine.[41]

Recognition that Palamas is in Accordance with the Earlier Church Fathers

After the triumph of the Palæologi, the Barlaamite faction convened an anti-Hesychast synod at Ephesus but, by this time, the patriarchs of Constantinople and the overwhelming majority of the clergy and laity had come to view the cause of Hesychasm as one and the same with that of Orthodoxy. Those who opposed it were accused of Latinizing. Martin Jugie states that the opposition of the Latins and the Latinophrones, who were necessarily hostile to the doctrine, actually contributed to its adoption, and soon Latinism and Antipalamism became equivalent in the minds of many Orthodox Christians.[41]

However, although the Barlaamites could no longer win over the hierarchy of the Eastern Orthodox Church in a synod, neither did they submit immediately to the new doctrine. Throughout the second half of the fourteenth century, there are numerous reports of Christians returning from the "Barlaamite heresy" to Palamite orthodoxy, suggesting that the process of imposing universal acceptance of Palamism spanned several decades.[37]

Callistus I and the ecumenical patriarchs who succeeded him mounted a vigorous campaign to have the new doctrine accepted by the other Eastern patriarchates as well as all the metropolitan sees under their jurisdiction. However, it took some time to overcome initial resistance to the doctrine. Manuel Kalekas reports on this repression as late as 1397. Examples of resistance included the metropolitan of Kiev and the patriarch of Antioch; similar acts of resistance were seen in the metropolitan sees that were governed by the Latins as well as in some autonomous ecclesiastical regions, such as the Church of Cyprus. However, by the end of the fourteenth century, Palamism had become accepted in those locations as well as in all the other Eastern patriarchates.[37]

One notable example of the campaign to enforce the orthodoxy of the Palamist doctrine was the action taken by patriarch Philotheos I to crack down on Demetrios and Prochorus Cydones. The two brothers had continued to argue forcefully against Palamism even when brought before the patriarch and enjoined to adhere to the orthodox doctrine. Finally, in exasperation, Philotheos convened a synod against the two Cydones in April 1368. However, even this extreme measure failed to effect the submission of Cydones and in the end, Prochorus was excommunicated and suspended from the clergy in perpetuity. The long tome that was prepared for the synod concludes with a decree canonizing Palamas who had died in 1359.[42]

Despite the initial opposition of the anti-Palamites and some patriarchates and sees, the resistance dwindled away over time and ultimately Palamist doctrine became accepted throughout the Eastern Orthodox Church. During this period, it became the norm for ecumenical patriarchs to profess the Palamite doctrine upon taking possession of their see.[37] For theologians who remained in opposition, there was ultimately no choice but to emigrate and convert to the Latin church, a path taken by Kalekas as well as Demetrios Kydones and Ioannes Kypariossiotes.

According to Aristeides Papadakis, "all (modern) Orthodox scholars who have written on Palamas — Lossky, Krivosheine, Papamichael, Meyendorff, Christou — assume his voice to be a legitimate expression of Orthodox tradition."[43]

The doctrine

Summarize

Perspective

In Eastern Orthodoxy, theology is not treated as an academic pursuit; instead, it is based on revelation (see gnosiology), meaning that Orthodox theology and its theologians are validated by ascetic pursuits, rather than academic degrees (i.e. scholasticism).[citation needed]

John Romanides quotes Saint Gregory of Nazianzus as asserting that one cannot be a genuine or a true theologian or teach knowledge of God without having experienced God, as is defined as the vision of God (theoria).[44] Theoria is obtained according to Eastern Orthodox theology by way of contemplative prayer called hesychasm and is the vision of God as the uncreated light i.e. the light of Tabor.[45][46][47] Palamas himself explicitly stated that he had seen the uncreated light of Tabor and had the vision of God called theoria.[48] Theosis is deification obtained through the practice of Hesychasm and theoria is one of its last stages as theosis is catharsis, theoria, and then completion of deification or theosis.[49]

Synodikon of the Sunday of Orthodoxy

The most recent set of anathemas that were added to the Synodikon of Orthodoxy is titled "Chapters against Barlaam and Akindynos"; these contain anathemas and acclamations that are the expression of the official Palamist doctrine.[37] The Synodikon thus canonizes the principal theses formulated by Gregory Palamas :

- The light which shone at Tabor, during the Transfiguration of the Savior, is declared to be neither a creature nor the essence of God, but the uncreated and natural grace and illumination fountaining eternally and inseparably from the divine essence itself: μήτε κτίσμα εἶναι θειότατον ἐκεῖνο φῶς μήτε οὐσίαν Θεοῦ, ἀλλ᾽ ἄκτιστον καὶ φυσικὴν χάριν καὶ ἔλλαμψιν ἐξ αὐτῆς τῆς θείας οὐσίας ἀχωρίστως ἀεὶ προϊοῦσαν (1st anathema).

- There are in God two inseparable things: the essence and the natural and substantial operation flowing from the essence in line with the relationship of cause and effect. The essence is imparticipable, the operation is participable; both the one and the other are uncreated and eternal: κατὰ τὸ τῆς Ἐκκλησίας εὐσεβὲς φρόνημα ὁμολογοῦμεν οὐσίαν ἐπὶ Θεοῦ καὶ οὐσιώδε καὶ φυσικὴν τούτου ἐνέργειαν ... εἶναι καὶ διαφορὰν ἀδιάστατον κατὰ τὰ ἄλλα καὶ μάλιστα τὰ αἴτιον καὶ αἰτιατόν, καὶ ἀμέθεκτον καὶ μεθεκτόν, τὸ μὲν τῆς οὐσίας, τὸ δὲ ἐνεργείας (2nd anathema).

- This real distinction between essence and operation does not destroy the simplicity of God, as the saints teach together with the pious mindset of the Church: κατὰ τὰς τῶν ἁγίων θεοπνεύστους θεολογίας καὶ τὸ τῆς Ἐκκλησίας εὐσεβὲς φρόνημα, μετὰ τῆς θεοπρεποῦς ταύτης διαφορᾶς καὶ τὴν θείαν ἁπλότητα πάνυ καλῶς διασώζεσθαι (4th anathema).

- The word θεότης does not apply solely to the divine essence, but is said also of its operation, according to the inspired teaching of the saints and the mindset of the Church.

- The light of Tabor is the ineffable and eternal glory of the Son of God, the kingdom of heaven promised to the saints, the splendor in which he shall appear on the last day to judge the living and the dead: δόξαν ἀπόρρητον τῆς θεότητος, ἄχρονον τοῦ Υἱοῦ δόξαν καὶ βασιλείαν καὶ κάλλος ἀληθινὸν καὶ ἐράσμιον (6th acclamation).

Essence–energies distinction

Addressing the question of how it is possible for man to have knowledge of a transcendent and unknowable God, Palamas drew a distinction between knowing God in his essence (Greek ousia) and knowing God in his energies (Greek energeiai). The divine energies concern the mutual relations between the Persons of the Trinity (within the divine life) and also God's relation with creatures, to whom they communicate the divine life.[50] According to Palamas, God's essence and his energies are differentiated from all eternity, and the distinction between them is not merely a distinction drawn by the human mind.[51] He maintained the Orthodox doctrine that it remains impossible to know God in His essence (to know who God is in and of Himself), but possible to know God in His energies (to know what God does, and who He is in relation to the creation and to man), as God reveals himself to humanity. In doing so, he made reference to the Cappadocian Fathers and other earlier Christian writers and Church fathers.[citation needed]

While critics of his teachings argue that this introduces an unacceptable division in the nature of God, Palamas' supporters argue that this distinction was not an innovation but had in fact been introduced in the 4th century writings of the Cappadocian Fathers. Gregory taught that the energies or operations of God were uncreated. He taught that the essence of God can never be known by his creature even in the next life, but that his uncreated energies or operations can be known both in this life and in the next, and convey to the Hesychast in this life and to the righteous in the next life a true spiritual knowledge of God. In Palamite theology, it is the uncreated energies of God that illumine the Hesychast who has been vouchsafed an experience of the Uncreated Light.[citation needed]

Historically, Western Christianity has tended to reject the essence–energies distinction, characterizing it as a heretical introduction of an unacceptable division in the Trinity and suggestive of polytheism.[6][7] Further, the associated practice of hesychasm used to achieve theosis was characterized as "magic".[4] Eastern Orthodox theologians have criticized Western theology, and its traditional theory that God is pure actuality in particular, for its alleged incompatibility with the essence–energies distinction.[52][53]

More recently, some Roman Catholic thinkers have taken a positive view of Palamas's teachings, including the essence–energies distinction, arguing that it does not represent an insurmountable theological division between Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.[8]

Theosis

According to the teachings of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, the quintessential purpose and goal of the Christian life is to attain theosis or 'deification', understood as 'likeness to' or 'union with' God. Theosis refers to the attainment of likeness to or union with God, as deification has three stages in its process of transformation. Theosis as such is the goal, it is the purpose of life, and it is considered achievable only through a synergy (or cooperation) between humans' activities and God's uncreated energies (or operations).[54][55][56]

Theosis results from leading a pure life, practicing restraint and adhering to the commandments, putting the love of God before all else. This metamorphosis (transfiguration) or transformation results from a deep love of God. Theoria is achieved by the pure of heart who are no longer subject to the afflictions of the passions.[57] It is a gift from the Holy Spirit to those who, through observance of the commandments of God and ascetic practices (see praxis, kenosis, Poustinia and schema), have achieved dispassion.[58] According to the standard ascetic formulation of this process, there are three stages: katharsis or purification, theoria or illumination, and theosis or deification (also referred to as union with God).[59]

Palamism uses the essence–energies distinction to explain how theosis is possible despite God's transcendence. According to Palamism, the divine essence remains transcendent and inaccessible, even after the Incarnation and the sending of the Holy Spirit.[60] Theosis is possible because of God's energies, "through which God becomes known to us and makes us share in the divine life".[1]

Theoria

In Eastern Orthodox theology, theoria refers to a stage of illumination on the path to theosis, in which one beholds God. Theosis is obtained by engaging in contemplative prayer resulting from the cultivation of watchfulness (Gk:nepsis). In its purest form, theoria is considered as the 'beholding', 'seeing' or 'vision' of God.[61]

Following Christ's instruction to "go into your room or closet and shut the door and pray to your father who is in secret" (Matthew 6:6), the hesychast withdraws into solitude in order that he or she may enter into a deeper state of contemplative stillness. By means of this stillness, the mind is calmed, and the ability to see reality is enhanced. The practitioner seeks to attain what the apostle Paul called 'unceasing prayer'.

Palamas synthesized the different traditions of theoria into an understanding of theoria that, through baptism, one receives the Holy Spirit. Through participation in the sacraments of the Church and the performance of works of faith, one cultivates a relationship with God. If one then, through willful submission to God, is devotional and becomes humble, akin to the Theotokos and the saints, and proceeds in faith past the point of rational contemplation, one can experience God. Palamas stated that this is not a mechanized process because each person is unique, but that the apodictic way that one experiences the uncreated light, or God, is through contemplative prayer called hesychasm. Theoria is cultivated through each of the steps of the growing process of theosis.

The only true way to experience Christ, according to Palamas, was the Eastern Orthodox faith. Once a person discovers Christ (through the Orthodox church), they begin the process of theosis, which is the gradual submission to the Truth (i.e. God) in order to be deified (theosis). Theoria is seen to be the experience of God hypostatically in person. However, since the essence of God is unknowable, it also cannot be experienced. Palamas expressed theoria as an experience of God as it happens to the whole person (soul or nous), not just the mind or body, in contrast to an experience of God that is drawn from memory, the mind, or in time.[62][63]

Hesychasm

Hesychasm is an eremitic tradition of prayer in the Eastern Orthodox Church, and some of the Eastern Catholic Churches, such as the Byzantine Rite, practised (Gk: ἡσυχάζω, hesychazo: "to keep stillness") by the Hesychast (Gr. Ἡσυχαστής, hesychastes).

Based on Christ's injunction in the Gospel of Matthew to "go into your closet to pray",[64] hesychasm in tradition has been the process of retiring inward by ceasing to register the senses, in order to achieve an experiential knowledge of God (see theoria).

Tabor Light

The Tabor Light refers to the light revealed on Mount Tabor at the Transfiguration of Jesus, identified with the light seen by Paul at his conversion.

Palamas taught that the "glory of God" revealed in various episodes of Jewish and Christian Scripture (e.g., the burning bush seen by Moses, the Light on Mount Tabor at the Transfiguration) was in fact the uncreated Energies of God (i.e., the grace of God). In opposition to this teaching, Barlaam held that they were created effects, because no part of God whatsoever could be directly perceived by humans. The Orthodox interpreted his position as denying the renewing power of the Holy Spirit, which, in the words of various Orthodox hymns, "made apostles out of fishermen" (i.e., makes saints even out of uneducated people). In his anti-hesychastic works Barlaam held that knowledge of worldly wisdom was necessary for the perfection of the monks and denied the possibility of the vision of the divine life.[citation needed]

Palamas taught that the truth is a person, Jesus Christ, a form of objective reality. In order for a Christian to be authentic, he or she must experience the Truth (i.e. Christ) as a real person (see hypostasis). Gregory further asserted that when Peter, James and John witnessed the Transfiguration of Jesus on Mount Tabor, that they were in fact seeing the uncreated light of God; and that it is possible for others to be granted to see that same uncreated light of God with the help of certain spiritual disciplines and contemplative prayer, although not in any automatic or mechanistic fashion.[citation needed]

Influence on the East–West Schism

The Hesychasm or Palamite controversy was not a conflict between Orthodoxy and the Papacy.[65] However, some Orthodox sources assert that it resulted in a direct theological conflict between Eastern Orthodox theology and the rise of Papal authority[66] and Western or Latin theology based on Scholasticism.[67]

In 1966, Nicholas Wiseman characterized Gregory Palamas as "the only major Orthodox spokesman since the schism with Rome" and asserted that a positive reassessment of his theology "would surely benefit the cause of unity."[68]

Initial Western reactions

Summarize

Perspective

While the Eastern Church went through a tempestuous period in which the controversy was heatedly debated resulting ultimately in a series of councils alternately approving and condemning doctrine concerning hesychasm, the Western Church paid scant attention to the controversy in the East and made no pronouncement about it, although Western theologians generally rejected the Palamite doctrine until the 20th century, when they began to "rediscover the riches of the Orthodox tradition".[69]

First encounter with the West

Between the years 1341 and 1368, negotiations between the Byzantine imperial court and the popes, aimed at bringing about a crusade against the Turks and a union of the Churches, were sporadic but continuous. There truly was never a lack of Latins in the East, and one could also find there Greeks who had converted to Catholicism. It was thus inevitable that the noise of the quarrel which was dividing the Byzantine Church into two rival factions would reach the ears of Westerners and, in particular, that the pope's legates would, one day or another, have to deal with it.

The pontifical legate, Paul of Smyrna, in the year 1355, attended, in company with John V Palaiologos, the public debate between Nikephoros Gregoras and Gregory Palamas. What impression Paul took away from this theological jousting match we can gather from a letter which he wrote to the pope and cardinals to give them an account of the discussions he had had with the ex-emperor John Kantakouzenos around 1366-1367. In this letter, published by Arcudius in Greek and Latin in his work Opusclua aurea theologica circa procession Spiritus Sancti (Rome, 1630) and reproduced in PG 154, 835-838, he notes that, having been sent by Urban V to the court of John V Palaiologos, he had attempted to form an opinion on Palamism, and had not succeeded in attaining a clear view of it:

"When I was attempting to learn the truth about this doctrine (he says), while living at Constantinople, when I had been sent to the emperor Palaiologos by the aforementioned supreme pontiff, I sought to know what it is, but was unable either by word or action to comprehend anything certain regarding this opinion and impious doctrine. For this reason, again, I was forced to attack them with harsh words and to provoke them, as it were, using certain arguments." (PG, loc. cit., col. 838.)

In 1366 it is clear that he had not comprehended anything. In 1355, after the dispute between the two protagonists, he was still very much in the dark about it. Nevertheless, he thought at one point that he had understood, after his conversations with Kantakouzenos, who had, at one point, conceded that between God's essence and his attributes, there is only a distinction of reason, κατ' ἐπίνοιαν. But he was soon disappointed when he read the account of these discussions, written by Kantakouzenos himself. Paul thought that the διαίρεσις πραγματική [real division], or even the διάκρισις πραγματική [real distinction], had been denied, and only the διαίρεσις κατ' ἐπίνοιαν [notional division] was admitted; but in fact a real difference, διαφορὰ πραγματική, was maintained. Kantakouzenos went on to say: ἄλλο ἡ οὐσία, ἄλλο ἡ ἐνέργεια, ἄλλο τὸ ἔχον, ἄλλο τὸ ἐχόμενον [the essence is one thing, the energy is another; that which has is one thing, that which is had is another]. Furthermore, he proclaimed the existence of a divine uncreated light, which was not identified with the divine essence: something which was absolutely unacceptable to western theology:

"Then he wrote about the light which appeared upon Mt. Tabor, asserting that it was uncreated and [yet] was not God's essence, but some sort of divine operation, which is a thing one cannot endure to hear: for nothing is uncreated apart from the divine essence." (PG 154, 838.)

The same letter of the patriarch Paul details that certain Greeks had kept the pope up to date about the Palamite error and had informed him that Kantakouzenos shared this error:

"Certain Greeks reported that the aforesaid emperor Kantakouzenos and the Church of the Greeks had introduced, into their doctrine, a multitude of divinities, superior and inferior, such that they claim that those things which are in God really differ among themselves."

Essence and energies distinction

From Palamas's time until the 20th century, Western theologians generally rejected the contention that, in the case of God, the distinction between essence and energies is real rather than notional (in the mind). In their view, affirming an ontological essence–energies distinction in God contradicted the teaching of the First Council of Nicaea[6] on divine unity.[7] According to Adrian Fortescue, the scholastic theory that God is pure actuality prevented Palamism from having much influence in the West, and it was from Western scholasticism that hesychasm's philosophical opponents in the East borrowed their weapons.[4]

Ludwig Ott held that a lack of distinction between the divine essence and the divine attributes was a dogma of the Roman Catholic Church,[70] adding, "In the Greek Church, the 14th century mystic-quietistic Sect of the Hesychasts or Palamites [...] taught a real distinction between the Divine Essence [...] and the Divine Efficacy or the Divine attributes."[71] In contrast, Jürgen Kuhlmann argues that the Roman Catholic Church never judged Palamism to be heretical, adding that Palamas did not consider that the distinction between essence and energies in God made God composite.[72] According to Kuhlmann, "the denial of a real distinction between essence and energies is not an article of Catholic faith".[73] The Enchiridion Symbolorum et Definitionum (Handbook of Creeds and Definitions), the collection of Roman Catholic teachings originally compiled by Heinrich Joseph Dominicus Denzinger, has no mention of the words "energies", "hesychasm" or "Palamas".[74]

Confusion with Quietism

Western theologians often equated Palamism with Quietism, an identification that may have been motivated in part by the fact that "quietism" is the literal translation of "hesychasm". However, according to Gordon Wakefield, "To translate 'hesychasm' as 'quietism', while perhaps etymologically defensible, is historically and theologically misleading." Wakefield asserts that "the distinctive tenets of the seventeenth century Western Quietists is not characteristic of Greek hesychasm."[75] Similarly, Kallistos Ware argues that it is important not to translate "hesychasm" as "quietism".[76][77]

Continuance into early 20th century

The opposition of Western theologians to Palamism continued into the early 20th century. In the Catholic Encyclopedia of 1909, Simon Vailhé accused Palamas's teachings that humans could achieve a corporal perception of the Divinity and his distinction between God's essence and his energies as "monstrous errors" and "perilous theological theories". He further characterized the Eastern canonization of Palamas's teachings as a "resurrection of polytheism".[78] Fortescue, also writing in the Catholic Encyclopedia, claimed that "the real distinction between God's essence and operation remains one more principle, though it is rarely insisted on now, in which the Orthodox differ from Catholics".[4]

Modern rediscovery of Palamas

Summarize

Perspective

Among Orthodox theologians

According to Norman Russell, Orthodox theology was dominated by an "arid scholasticism" for several centuries after the fall of Constantinople. Russell asserts that, after the Second World War, modern Greek theologians have re-engaged with the Greek Fathers with the help of diaspora theologians and Western patristic scholars.[79] Included in this re-engagement with the Greek Fathers has been a rediscovery of Palamas by Greek theologians.[80]

According to Michael Angold, the "rediscovery of [Palamas'] writings by theologians of the last century has played a crucial role in the construction of present-day Orthodoxy.[81] A pioneering work was Gregorios Papamichael's, Ο Άγιος Γρηγόριος ο Παλαμάς (St Petersburg/Alexandria, 1911),[82] a serious study which had, however, little impact on Orthodox theology at the time. It was of course Vladimir Lossky, in his Essai sur la théologie mystique de l'Eglise d'Orient (Paris, 1944; English translation, London, 1957), who first brought Palamism to the attention of a wider public, non-Orthodox as well as Orthodox.[83]

Roman Catholic Jean-Yves Lacoste describes Meyendorff's characterization of Palamas' theology and the reception of Meyendorff's thesis by the Orthodox world of the latter half of the 20th century:

For J. Meyendorff, Gregory Palamas has perfected the patristic and concilar heritage, against the secularizing tide that heralds the Renaissance and the Reformation, by correcting its Platonizing excesses along biblical and personalist lines. Palamitism, which is impossible to compress into a system, is then viewed as the apophatic expression of a mystical existentialism. Accepted by the Orthodox world (with the exception of Romanides), this thesis justifies the Palamite character of contemporary research devoted to ontotheological criticism (Yannaras), to the metaphysics of the person (Clement), and to phenomenology of ecclesiality (Zizioulas) or of the Holy Spirit (Bobrinskoy).[84]

A number of Orthodox theologians such as John Romanides have criticized Meyendorff's understanding of Palamas. Romanides criticizes Meyendorff's analysis of the disagreement between Palamas and Barlaam, as well as Meyendorff's claim that the disagreement represents an internal conflict within Byzantine theology rather than "a clash between Franco-Latin and East Roman theology, as has been generally believed".[85] Romanides also criticizes Meyendorff for attributing numerous "originalities" to Palamas and for portraying Palamas as applying "Christological correctives" to the Platonism of Dionysius the Areopagite.[86] According to Duncan Reid, the debate between Meyendorff and Romanides centered on the relationship between nominalism and Palamite theology.[87]

Orthodox Christian Clark Carlton, host of Ancient Faith Radio, has objected to the term "Palamism". According to Carlton, Palamas's teachings express an Orthodox tradition that long preceded Palamas, and "Roman Catholic thinkers" coined the term "Palamism" in order to "justify their own heresy by giving what is the undoubted and traditional teaching of the Orthodox Church an exotic label, turning it into an historically conditioned 'ism'".[88]

Among Western theologians

Jeffrey D. Finch asserts that "the future of East–West rapprochement appears to be overcoming the modern polemics of neo-scholasticism and neo-Palamism".[89]

The last half of the twentieth century saw a remarkable change in the attitude of Roman Catholic theologians to Palamas, a "rehabilitation" of him that has led to increasing parts of the Western Church considering him a saint, even if formally uncanonized.[6] The work of Orthodox theologian, John Meyendorff, is considered to have transformed the opinion of the Western Church regarding Palamism. Patrick Carey asserts that, before Meyendorff's 1959 doctoral dissertation on Palamas, Palamism was considered by Western theologians to be a "curious and sui generis example of medieval Byzantium's intellectual decline". Andreas Andreopoulos cites the 1910 Catholic Encyclopedia article by Fortescue as an example of how Barlaam's distrustful and hostile attitude regarding hesychasm survived until recently in the West, adding that now "the Western world has started to rediscover what amounts to a lost tradition. Hesychasm, which was never anything close to a scholar's pursuit, is now studied by Western theologians who are astounded by the profound thought and spirituality of late Byzantium."[90] Carey characterizes Meyendorff's thesis as a landmark study of Palamas that "set Palamas firmly within the context of Greek patristic thought and spirituality" with the result that Palamism is now generally understood to be "a faithful witness to the long-standing Eastern Christian emphasis on deification (theosis) as the purpose of the divine economy in Christ."[91] Meyendorff himself describes the twentieth-century rehabilitation of Palamas in the Western Church as a "remarkable event in the history of scholarship."[92] According to Kallistos Ware, some Western theologians, both Roman Catholic and Anglican, see the theology of Palamas as introducing an inadmissible division within God.[93] However, some Western scholars maintain that there is no conflict between Palamas's teaching and Roman Catholic thought.[94] For example, G. Philips asserts that the essence–energies distinction as presented by Palamas is "a typical example of a perfectly admissible theological pluralism" that is compatible with the Roman Catholic magisterium.[95] Some Western theologians have incorporated the essence–energies distinction into their own thinking.[96]

Some Roman Catholic writers, in particular G. Philips and A.N. Williams, deny that Palamas regarded the distinction between the Essence and Energies of God as a real distinction,[97] and Orthodox theologian David Bentley Hart also indicated his hesitancy to accept the view that for Palamas it was, in the full scholastic sense, a real distinction,[98] rather than a formal distinction in the Scotist sense.

See also

- Barlaam of Calabria

- Barlaamism

- Deification in Christianity

- Eastern Orthodox theology

- Fifth Council of Constantinople

- Gennadius Scholarius

- Gregory Akindynos

- Hesychast controversy

- Isidore I of Constantinople

- John Kyparissiotes

- John XIV of Constantinople

- Mark of Ephesus

- Neo-Palamism

- Nicephorus Gregoras

- Ousia-energeia distinction

- Scotism

- Orthodox–Roman Catholic theological differences

- Theosis

Notes

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.