Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Oregon and California Railroad Revested Lands

2 million acres of land managed by the US' BoLM From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

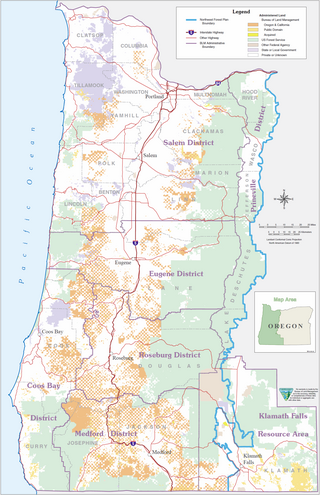

The Oregon and California Railroad Revested Lands (commonly known as O&C Lands), are approximately 2,600,000 acres (1,100,000 ha) of land located in eighteen counties of western Oregon. Originally granted to the Oregon & California Railroad to build a railroad between Portland, Oregon and San Francisco, California, the land was reconveyed to the United States government by act of Congress in 1916 and is currently managed by the United States Bureau of Land Management.

BLM: Oregon & California

BLM: Public domain

BLM: Acquired

U.S. Forest Service

Other Federal agency

State or local government

Private or unknown

BLM administrative boundary

Since 1916, the 18 counties where the O&C lands are located have received payments from the United States government at 50% share of timber revenue on those lands. Later, as compensation for the loss of timber and tax revenue decreased, the government added federal revenues. The governments of several of the counties have come to depend upon the O&C land revenue as an important source of income for schools and county services.

The most recent source of income from the lands was funded through an extension of the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000 which allocated $110 million to the counties. The act has been renewed each succeeding year at vastly reduced spending levels, most recently for $26 million in 2022.[2] In late 2013, the United States House of Representatives considered a bill that would resume the funding and increase timber harvests to provide additional income to the counties.[3]

Remove ads

Origin

Summarize

Perspective

As part of the U.S. government's desire to foster settlement and economic development in the western states, in July 1866, Congress passed the Oregon and California Railroad Act. This act made 3,700,000 acres (1,500,000 ha) of land available for any company that built a railroad from Portland to San Francisco. The land was to be distributed by the state of Oregon in 12,800-acre (5,200 ha) land grants for each mile of track completed.[4][5] Two companies, both of which named themselves the Oregon Central Railroad, began a competition to build the railroad, one on the west side of the Willamette River and one on the east side. The two lines would eventually merge and reorganize as the Oregon and California Railroad.[5] In 1869, Congress changed how the grants were to be distributed, requiring the railroads to sell land along the line to settlers in 160-acre (65 ha) parcels at $2.50 per acre.[5] The land was distributed in a checkerboard pattern, with sections laid out for 20 miles (32 km) on either side of the rail corridor with the government retaining the alternate sections for future growth.[6]

By 1872, the railroad had extended from Portland to Roseburg.[5] Along the way, it created growth in Willamette Valley towns such as Canby, Aurora, and Harrisburg, which emerged as freight and passenger stations, and provided a commercial lifeline to the part of the river valley above Harrisburg where steamships were rarely able to travel.[5] As the railroad made its way into the Umpqua Valley, new townsites such as Drain, Oakland, and Yoncalla were laid out.[5]

Remove ads

Land fraud

Summarize

Perspective

Perhaps the most significant aspect of the railroad was that it provided access to Oregon's vast forests for large-scale logging operations.[5] But despite the large number of grants, it was difficult to sell to actual settlers because much of the land was not only heavily forested (chiefly in Douglas-fir and Western Hemlock), but rugged and remote; moreover, the railroads soon realized that the land was much more valuable if sold in larger plots to developers and timber companies.[7] As a result, some individuals posed as settlers to purchase the land at the $2.50 per acre rate and then promptly deeded them back to the railroad, which amassed the smaller plots into larger ones and resold them at a higher price to timber interests.[7]

A scheme to circumvent the settler grants altogether soon emerged. A railroad official hired a surveyor and logger named Stephen A. Douglas Puter to round up people from Portland saloons, and then take them to the land office where they would register for an O&C parcel as a settler, and then promptly resell to the railroad for bundling with other plots and resale to the highest bidder, typically as much as $40 an acre.[8] In 1904, an investigation by The Oregonian uncovered the scandal, by which time it had grown to such a magnitude that the paper reported that more than 75% of the land sales had violated federal law.[9]

Between 1904 and 1910, nearly a hundred people were indicted in connection with the fraud, including U.S. Senator John H. Mitchell, U.S. Representatives John N. Williamson and Binger Hermann, and U.S. Attorney John Hicklin Hall.[10][11][12]

Remove ads

Revestiture of lands

Summarize

Perspective

As the land fraud trials reached their conclusion, attention also turned to the Southern Pacific Railroad (which had acquired the O&C in 1887). Not only had the company violated the terms of the grant agreement, but in 1903, declared it was terminating land sales—in violation of the grant agreement—either as a hedge against future increases in land values or to retain the timber profits for itself.[7][9][13]

A series of lawsuits between the State of Oregon, the United States government, and the railroads ensued. Another lawsuit was brought by Portland attorney and future U.S. Representative Walter Lafferty on behalf of 18 western Oregon counties, which sued to claim revenue from timber sales on the O&C lands.[14] The cases worked their way up to the United States Supreme Court, which ruled in 1915 in Oregon & California R. Co. v. United States that despite the violation of grant terms, the railroad had been built and the railroad company should be compensated. In 1916, Congress passed the Chamberlain–Ferris Act, which revested the remaining 2,800,000 acres of land to the United States government, and compensated the railroad at $2.50 per acre from an account, the Oregon and California land grant fund, funded by timber sales from the land. Oregon counties affected by the revestiture of land were also to be compensated from the fund.[8][9][15][16]

The Chamberlain–Ferris Act did not ease the financial trouble faced by many of the O&C counties; very little timber revenue was actually generated from the land, and many counties now had large percentages of their land owned by the federal government, denying them a source of property tax revenue.[7][17] As these problems compounded into the 1920s, the 18 counties organized the Association of O&C Counties (AOCC) to give itself a voice in Washington, D.C. One of its cofounders, Douglas County district attorney and future U.S. Senator Guy Cordon, began lobbying Oregon's congressional delegation for relief.[5][18] In 1926, a bill introduced by Oregon Senator Robert N. Stanfield, which became known as the Stanfield Act, was passed. This law provided that the U.S. government pay the counties in lieu of property taxes they would have received if the land were privately owned.[5][17][19][20][21] But since the U.S. government was to be reimbursed from timber revenues, and since timber revenue remained low, very few payments were actually made to the counties, and Congress began to work on new legislation.[17][19][22]

Remove ads

The O&C Act

Summarize

Perspective

In 1937, Congress again sought to ensure federal funding for the 18 O&C counties. The Oregon and California Revested Lands Sustained Yield Management Act of 1937 (43 U.S.C. § 2601), commonly referred as the O&C Act, directed the United States Department of the Interior to harvest timber from the O&C lands (as well as the Coos Bay Wagon Road Lands) on a sustained yield basis.[8][17] The legislation returned 50 percent of timber sales receipts to the counties, and 25 percent to the U.S. Treasury to reimburse the federal government for payments made to the counties prior to establishment of the Act.[5] The law specifically provided that the lands be managed, including reforestation and protection of watershed, to ensure a permanent source of timber, and therefore, revenue to the counties.[23]

Under the O&C Act, the Department of the Interior under its United States General Land Office and later succeeded by the Bureau of Land Management, managed more than 44 billion board feet of standing inventory in 1937 into more than 60 billion board feet by the mid-1990s, and harvested more than 44 billion board feet over that time period.[17] In 1951, the U.S. Treasury had been fully reimbursed, and the 25 percent of the revenue that had previously gone to the Treasury now reverted to the counties; in 1953, the counties opted to divert that money to maintenance of the land and roads, reforestation, as well as recreational facilities and other improvements.[5][7][24] A 1970 GAO report contained an estimate that from its implementation through 1969, the counties had received a total of $300 million as a result of the Act.[25] The authors of the report also estimated that most counties received more from the government payments than they would have if the land had been held privately.[25]

The O&C Act achieved what the previous legislation had failed to do: provide a stable revenue to the counties. This revenue became a vital part of the budgets of the O&C counties, paying for county-provided services such as law enforcement and corrections and health and social services.[24] With this funding seemingly guaranteed, the counties kept other taxes much lower than other counties in the state, increasing their dependence on the timber payments. For example, the property tax in Curry County is 60 cents per $1,000 of assessed value, far below the state average of $2.81 per $1000.[26]

Remove ads

Decline in timber revenue and revised Congressional action

Summarize

Perspective

In 1989, annual timber harvest revenue on federal forest land nationwide peaked at $1.5 billion.[27] Following that year, the impact of overharvesting and increased environmental concerns began to negatively impact timber sales on the O&C lands.[7] In 1994, the federal Northwest Forest Plan was implemented. Designed to guide forest management of federal lands while protecting old-growth forest habitat for endangered species such as the Northern spotted owl, the plan restricted the land available for timber harvest. By 1998, revenue on federal forest lands fell to a third of the peak 1989 revenue, with areas in the Northwest particularly hard-hit.[7][27]

To offset the effects of the loss of timber revenue, in 1993, President Bill Clinton proposed a 10-year program of payments, set at 85 percent of the average O&C Act payments from 1986 to 1990, and declining 3 percent annually.[28] These "spotted owl" or "safety net" payments were passed by Congress as part of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 (Pub. L. 103–66).[27][28]

With the payments set to expire in 2003, work began in 1999 to seek an extension to the payments. The O&C counties joined with other rural counties (including 15 of Oregon's other 18 counties) that also faced falling timber revenues to lobby Congress for another solution.[17] In 2000, Congress passed the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act (Pub. L. 106–393 (text) (PDF)), which authorizes western counties, including the O&C counties, to receive federal payments to compensate for loss of timber revenue until 2006. Payments to O&C counties, which included O&C revenue as well as revenue on Forest Service land, averaged about $250 million per year from 2000 to 2006.[28][29] The act was extended for one year in 2007, and in 2008, a four-year extension was included in the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 that phased out the program by 2012.[6][30] The extension expired on September 30, 2011, and the final payment of just over $40 million was delivered to the O&C counties in early 2012.[31]

In late 2011, Oregon Senators Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley proposed legislation to extend the payments for another five years. The move was backed by Governor John Kitzhaber and the entire Oregon congressional delegation.[32] Republican and Democratic members of Oregon's congressional delegation also proposed setting aside some of the federal land in Oregon as public trusts in which half would be designated for harvest to provide revenue for the counties, and half designated as a conservation area.[29] President Barack Obama's proposed 2013 United States federal budget included $294 million to extend the program for fiscal year 2013 with a plan to continue the payments for four more years, with the amount declining 10% each year.[33][34]

In March 2012, the U.S. Senate added an amendment to the surface transportation bill that authorized a one-year extension to the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act. Oregon counties would have received a total of $102 million from the legislation in 2012, to be divided among all 33 counties that currently receive payments. In 2008, Oregon received $250 million from the program.[35] The full transportation bill, including the amendment, passed the Senate by a 74–22 vote,[35][36] but the U.S. House of Representatives refused to vote on the Senate bill, instead passing a three-month extension to the current transportation bill that did not contain a county payments extension.[37] In July 2012, the Secure Rural Schools Act renewal amendment was included in the transportation bill approved by Congress and signed by the President.[38][39][40] This was widely expected to be the last renewal of the program,[38] but in September 2013, Congress passed another one-year extension to the program, though again at reduced levels.[41]

Remove ads

Future of the O&C counties

Summarize

Perspective

With future revenue uncertain, several Oregon counties now face a severe financial crisis to pay for county services, including law enforcement, social services, justice and corrections systems, election services and road maintenance among others.[26] With county services required by state law and bankruptcy not permitted, counties have considered merging to save costs, and explored new sources of revenue.[26]

One of the hardest-hit counties, Curry County, introduced a ballot measure to add a 3% sales tax to pay for county services.[42] Oregon is one of only five states in the United States with no county or state sales tax, and the tax has been voted down regularly by voters whenever it has been proposed (though some areas assess a gas tax, and two cities in tourist areas, Ashland and Yachats, assess a local tax on prepared food).[42] In Josephine County, after a proposed property tax increase to pay for law enforcement was defeated in May 2012, the sheriff's office reduced its staff by 2/3 and released inmates from the county jail to reduce spending.[43] Lane County released 96 prisoners from its prisons and laid off 40 law enforcement personnel to cut costs.[44]

In 2012, the Oregon Legislative Assembly passed a law to allow O&C counties to use timber funds previously reserved for road maintenance to pay for law enforcement patrols.[45]

In late 2013, the House passed a forest management bill co-sponsored by Oregon Representatives Peter DeFazio, Greg Walden, and Kurt Schrader that would include increased timber harvests on O&C lands along with resumption of some Secure Rural Schools funding.[3]

Remove ads

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads