Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

The Nutcracker

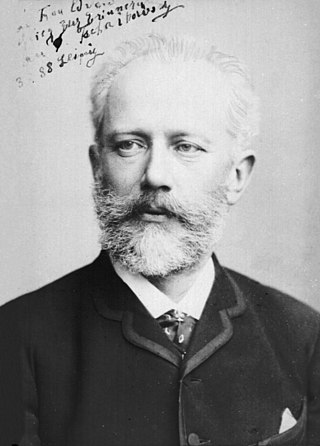

1892 ballet by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Remove ads

The Nutcracker (Russian: Щелкунчик[a], romanized: Shchelkunchik, pronounced [ɕːɪɫˈkunʲt͡ɕɪk] ⓘ), Op. 71, is an 1892 two-act classical ballet (conceived as a ballet-féerie; Russian: балет-феерия, romanized: balet-feyeriya) by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, set on Christmas Eve at the foot of a Christmas tree in a child's imagination featuring a Nutcracker doll. The plot is an adaptation of Alexandre Dumas's 1844 short story The Nutcracker, itself a retelling of E. T. A. Hoffmann's 1816 short story The Nutcracker and the Mouse King. The ballet's first choreographer was Marius Petipa, with whom Tchaikovsky had worked three years earlier on The Sleeping Beauty, assisted by Lev Ivanov. Although the complete and staged The Nutcracker ballet was not initially as successful as the 20-minute Nutcracker Suite that Tchaikovsky had premiered nine months earlier, it became popular in later years.

Since the late 1960s, The Nutcracker has been danced by many ballet companies, especially in North America.[1] Major American ballet companies generate around 40% of their annual ticket revenues from performances of the ballet.[2][3] Its score has been used in several film adaptations of Hoffmann's story.

Tchaikovsky's score has become one of his most famous compositions. Among other things, the score is noted for its use of the celesta, an instrument the composer had already employed in his much lesser known symphonic ballad The Voyevoda (1891).

Remove ads

Composition

Summarize

Perspective

After the success of The Sleeping Beauty in 1890, Ivan Vsevolozhsky, the director of the Imperial Theatres, commissioned Tchaikovsky to compose a double-bill program featuring both an opera and a ballet. The opera would be Iolanta. For the ballet, Tchaikovsky would again join forces with Marius Petipa, with whom he had collaborated on The Sleeping Beauty. The material Vsevolozhsky chose was an adaptation of E. T. A. Hoffmann's story "The Nutcracker and the Mouse King", by Alexandre Dumas called "The Story of a Nutcracker".[4] The plot of Hoffmann's story (and Dumas's adaptation) was greatly simplified for the two-act ballet. Hoffmann's tale contains a long flashback story within its main plot titled "The Tale of the Hard Nut", which explains how the Prince was turned into the Nutcracker. This had to be excised for the ballet.[5]

Petipa gave Tchaikovsky extremely detailed instructions for the composition of each number, down to the tempo and number of bars.[4] The completion of the work was interrupted for a short time when Tchaikovsky visited the United States for twenty-five days to conduct concerts for the opening of Carnegie Hall.[6] Tchaikovsky composed parts of The Nutcracker in Rouen, France.[7]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Saint Petersburg premiere

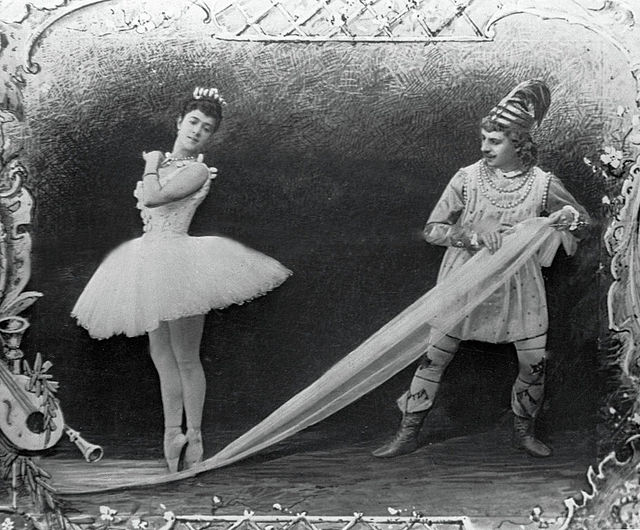

The first performance of the ballet was held as a double premiere together with Tchaikovsky's last opera, Iolanta, on 18 December [O.S. 6 December] 1892, at the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg, Russia.[8] Although the libretto was by Marius Petipa, who exactly choreographed the first production has been debated. Petipa began work on the choreography in August 1892; however, illness removed him from its completion and his assistant of seven years, Lev Ivanov, was brought in. Although Ivanov is often credited as the choreographer, some contemporary accounts credit Petipa. The performance was conducted by Italian composer Riccardo Drigo, with Antonietta Dell'Era as the Sugar Plum Fairy, Pavel Gerdt as Prince Coqueluche, Stanislava Belinskaya as Clara, Sergei Legat as the Nutcracker-Prince, and Timofey Stukolkin as Drosselmeyer. Unlike in many later productions, the children's roles were performed by real children – students of the Imperial Ballet School in Saint Petersburg, with Belinskaya as Clara, and Vassily Stukolkin as Fritz – rather than adults.

The first performance of The Nutcracker was not deemed a success.[9] The reaction to the dancers themselves was ambivalent. Although some critics praised Dell'Era on her pointework as the Sugar Plum Fairy (she allegedly received five curtain-calls), one critic called her "corpulent" and "podgy". Olga Preobrajenskaya as the Columbine doll was panned by one critic as "completely insipid" and praised as "charming" by another.[10]

Alexandre Benois described the choreography of the battle scene as confusing: "One can not understand anything. Disorderly pushing about from corner to corner and running backwards and forwards – quite amateurish."[10]

The libretto was criticized as "lopsided"[11] and for not being faithful to the Hoffmann tale. Much of the criticism focused on the featuring of children so prominently in the ballet,[12] and many bemoaned the fact that the ballerina did not dance until the Grand Pas de Deux near the end of the second act (which did not occur until nearly midnight during the program).[11] Some found the transition between the mundane world of the first scene and the fantasy world of the second act too abrupt.[4] Reception was better for Tchaikovsky's score. Some critics called it "astonishingly rich in detailed inspiration" and "from beginning to end, beautiful, melodious, original, and characteristic".[13] But this also was not unanimous, as some critics found the party scene "ponderous" and the Grand Pas de Deux "insipid".[14]

Subsequent productions

In 1919, choreographer Alexander Gorsky staged a production which eliminated the Sugar Plum Fairy and her Cavalier and gave their dances to Clara and the Nutcracker Prince, who were played by adults instead of children. This was the first production to do so. An abridged version of the ballet was first performed outside Russia in Budapest (Royal Opera House) in 1927, with choreography by Ede Brada.[15][unreliable source?] In 1934, choreographer Vasili Vainonen staged a version of the work that addressed many of the criticisms of the original 1892 production by casting adult dancers in the roles of Clara and the Prince, as Gorsky had. The Vainonen version influenced several later productions.[4]

The first complete performance outside Russia took place in England in 1934,[9] staged by Nicholas Sergeyev after Petipa's original choreography. Annual performances of the ballet have been staged there since 1952.[16] Another abridged version of the ballet, performed by the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, was staged in New York City in 1940,[17] Alexandra Fedorova – again, after Petipa's version.[9] The ballet's first complete United States performance was on 24 December 1944 by the San Francisco Ballet, staged by its artistic director, Willam Christensen, and starring Gisella Caccialanza as the Sugar Plum Fairy, and Jocelyn Vollmar as the Snow Queen.[18][9] After the enormous success of this production, San Francisco Ballet has presented Nutcracker every Christmas Eve and throughout the winter season, debuting new productions in 1944, 1954, 1967, and 2004. The original Christensen version continues in Salt Lake City, where Christensen relocated in 1948. It has been performed every year since 1963 by the Christensen-founded Ballet West.[19]

The New York City Ballet gave its first annual performance of George Balanchine's reworked staging of The Nutcracker in 1954.[9] The performance of Maria Tallchief in the role of the Sugar Plum Fairy helped elevate the work from obscurity into an annual Christmas classic and the industry's most reliable box-office draw. Critic Walter Terry remarked that "Maria Tallchief, as the Sugar Plum Fairy, is herself a creature of magic, dancing the seemingly impossible with effortless beauty of movement, electrifying us with her brilliance, enchanting us with her radiance of being. Does she have any equals anywhere, inside or outside of fairyland? While watching her in The Nutcracker, one is tempted to doubt it."[20]

Since Gorsky, Vainonen and Balanchine's productions, many other choreographers have made their own versions. Some institute the changes made by Gorsky and Vainonen while others, like Balanchine, utilize the original libretto. Some notable productions include Rudolf Nureyev's 1963 production for the Royal Ballet, Yury Grigorovich for the Bolshoi Ballet, Mikhail Baryshnikov for the American Ballet Theatre, Fernand Nault for Les Grands Ballets Canadiens starting in 1964, Kent Stowell for Pacific Northwest Ballet starting in 1983, and Peter Wright for the Royal Ballet and the Birmingham Royal Ballet. In recent years, revisionist productions, including those by Mark Morris, Matthew Bourne, and Mikhail Chemiakin have appeared; these depart radically from both the original 1892 libretto and Vainonen's revival, while Maurice Béjart's version completely discards the original plot and characters. In addition to annual live stagings of the work, many productions have also been televised or released on home video.[1]

Remove ads

Roles

Summarize

Perspective

The following extrapolation of the characters (in order of appearance) is drawn from an examination of the stage directions in the score.[21]

Act I

- Herr Stahlbaum

- His wife

- His children, including:

- Clara, his daughter, sometimes known as Marie or Masha

- Fritz, his son

- Louise, his daughter

- Children Guests

- Parents dressed as incroyables

- Herr Drosselmeyer

- His nephew (in some versions) who resembles the Nutcracker Prince and is played by the same dancer

- Dolls (spring-activated, sometimes all three dancers instead):

- Harlequin and Columbine, appearing out of a cabbage (1st gift)

- Vivandière and a Soldier (2nd gift)

- Nutcracker (3rd gift, at first a normal-sized toy, then full-sized and "speaking", then a Prince)

- Owl (on clock, changing into Drosselmeyer)

- Mice

- Sentinel (speaking role)

- The Bunny

- Soldiers (of the Nutcracker)

- Mouse King

- Snowflakes (sometimes Snow Crystals, sometimes accompanying a Snow Queen and King)

Act II

- Angels and/or Fairies

- Sugar Plum Fairy

- Clara/Marie

- The Nutcracker Prince

- 12 Pages

- Eminent members of the court

- Spanish dancers (Chocolate)

- Arabian dancers (Coffee)

- Chinese dancers (Tea)

- Russian dancers (Candy Canes)

- Danish shepherdesses / French mirliton players (Marzipan)

- Mother Ginger

- Polichinelles (Mother Ginger's Children)

- Dewdrop

- Flowers

- Sugar Plum Fairy's Cavalier

Plot

Summarize

Perspective

Below is a synopsis based on the original 1892 libretto by Marius Petipa. The story varies from production to production, though most follow the basic outline. The names of the characters also vary. In the original Hoffmann story, the young heroine is called Marie Stahlbaum and Clara (Klärchen) is her doll's name. In the adaptation by Dumas on which Petipa based his libretto, her name is Marie Silberhaus.[5] In still other productions, such as Balanchine's, Clara is Marie Stahlbaum rather than Clara Silberhaus.

Act I

Scene 1: The Stahlbaum Home

In Nuremberg, Germany on Christmas Eve in the 1820s, a family and their friends gather in the parlor to decorate the Christmas tree in preparation for the party. Once the tree is finished, the children are summoned.

When the party begins,[22] presents are given out to the children. When the owl-topped grandfather clock strikes eight, a mysterious figure enters the room. It is Drosselmeyer—a councilman, magician, and Clara's godfather. He is also a talented toymaker who has brought with him gifts for the children, including four lifelike dolls who dance to the delight of all.[23] He then has them put away for safekeeping.

Clara and her brother Fritz are sad to see the dolls being taken away, but Drosselmeyer has yet another toy for them: a wooden nutcracker doll, which the other children ignore. Clara immediately takes a liking to it, but Fritz accidentally breaks it. Clara is heartbroken, but Drosselmeyer fixes the nutcracker, much to everyone's relief.

During the night, after everyone else has gone to bed, Clara returns to the parlor to check on the nutcracker. As she reaches the small bed, the clock strikes midnight and she looks up to see Drosselmeyer perched atop it. Suddenly, mice begin to fill the room and the Christmas tree begins to grow to dizzying heights. The nutcracker also grows to life size. Clara finds herself in the midst of a battle between an army of gingerbread soldiers and the mice, led by their king.

The nutcracker appears to lead the gingerbread men, who are joined by tin soldiers, and by dolls who serve as doctors to carry away the wounded. As the seven-headed Mouse King advances on the still-wounded nutcracker, Clara throws her slipper at him, distracting him long enough for the nutcracker to stab him.[24]

Scene 2: A Pine Forest

The mice retreat and the nutcracker is transformed into a human prince.[25] He leads Clara through the moonlit night to a pine forest in which the snowflakes dance around them, beckoning them on to his kingdom as the first act ends.[26][27]

Act II

The Land of Sweets

Clara and the Prince travel to the beautiful Land of Sweets, ruled by the Sugar Plum Fairy in the Prince's place until his return. He recounts for her how he had been saved from the Mouse King by Clara and transformed back into himself. In honor of the young heroine, a celebration of sweets from around the world is produced: chocolate from Spain, coffee from Arabia,[28][29] tea from China,[30] and candy canes from Russia[31] all dance for their amusement; Marzipan shepherdesses perform on their flutes;[32] Mother Ginger has her children, the Polichinelles, emerge from under her enormous hoop skirt to dance; a string of beautiful flowers performs a waltz.[33][34] To conclude the night, the Sugar Plum Fairy and her Cavalier perform a dance.[35][36]

A final waltz is performed by all the sweets, after which the Sugar Plum Fairy ushers Clara and the Prince down from their throne. He bows to her, she kisses Clara goodbye, and leads them to a reindeer-drawn sleigh. It takes off as they wave goodbye to all the subjects who wave back.

In the original libretto, the ballet's apotheosis "represents a large beehive with flying bees, closely guarding their riches".[37] Just like Swan Lake, there have been various alternative endings created in productions subsequent to the original.

Remove ads

Musical sources and influences

Summarize

Perspective

The Nutcracker is one of the composer's most popular compositions. The music belongs to the Romantic period and contains some of his most memorable melodies, several of which are frequently used in television and film. (They are often heard in TV commercials shown during the Christmas season.[38])

Tchaikovsky is said to have argued with a friend who wagered that the composer could not write a melody based on a one-octave scale in sequence. Tchaikovsky asked if it mattered whether the notes were in ascending or descending order and was assured it did not. This resulted in the Adagio from the Grand pas de deux, which, in the ballet, nearly always immediately follows the "Waltz of the Flowers". A story is also told that Tchaikovsky's sister Alexandra (9 January 1842 — 9 April 1891[39]) had died shortly before he began composition of the ballet and that his sister's death influenced him to compose a melancholy, descending scale melody for the adagio of the Grand Pas de Deux.[40] However, it is more naturally perceived as a dreams-come-true theme because of another celebrated scale use, the ascending one in the Barcarolle from The Seasons.[41]

Tchaikovsky was less satisfied with The Nutcracker than with The Sleeping Beauty. (In the film Fantasia, commentator Deems Taylor observes that he "really detested" the score.) Tchaikovsky accepted the commission from Vsevolozhsky but did not particularly want to write the ballet[42] (though he did write to a friend while composing it, "I am daily becoming more and more attuned to my task").[43]

Remove ads

Instrumentation

The music is written for an orchestra with the following instrumentation.

|

|

Voice

|

Remove ads

Musical scenes

Summarize

Perspective

From the Imperial Ballet's 1892 program

Titles of all of the numbers listed here come from Marius Petipa's original scenario as well as the original libretto and programs of the first production of 1892. All libretti and programs of works performed on the stages of the Imperial Theatres were titled in French, which was the official language of the Imperial Court, as well as the language from which balletic terminology is derived.

Casse-Noisette. Ballet-féerie in two acts and three tableaux with apotheosis.

|

Act I

|

Act II

|

Structure

List of acts, scenes (tableaux) and musical numbers, along with tempo indications. Numbers are given according to the original Russian and French titles of the first edition score (1892), the piano reduction score by Sergei Taneyev (1892), both published by P. Jurgenson in Moscow, and the Soviet collected edition of the composer's works, as reprinted Melville, New York: Belwin Mills [n.d.][44]

Remove ads

Concert excerpts and arrangements

Summarize

Perspective

Tchaikovsky: The Nutcracker Suite, Op. 71a

Tchaikovsky made a selection of eight of the numbers from the ballet before the ballet's December 1892 première, forming The Nutcracker Suite, Op. 71a, intended for concert performance. The suite was first performed, under the composer's direction, on 19 March 1892 at an assembly of the Saint Petersburg branch of the Musical Society.[46] The suite became instantly popular, with almost every number encored at its premiere,[47] while the complete ballet did not begin to achieve its great popularity until after the George Balanchine staging became a hit in New York City.[48] The suite became very popular on the concert stage, and was excerpted in Disney's Fantasia, omitting the two movements prior to the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy. The outline below represents the selection and sequence of the Nutcracker Suite made by the composer:

- Miniature Overture (B-Flat Major)

- Characteristic Dances

- March (G Major)

- Dance of the Sugar-Plum Fairy (E Minor) [ending altered from ballet version]

- Russian Dance (Trepak) (G Major)

- Arabian Dance (coffee) (G Minor)

- Chinese Dance (tea) (B-Flat Major)

- Dance of the Reed Flutes (Mirlitons) (D Major)

- Waltz of the Flowers (D Major)

Grainger: Paraphrase on Tchaikovsky's Flower Waltz, for solo piano

The Paraphrase on Tchaikovsky's Flower Waltz is a successful piano arrangement from one of the movements from The Nutcracker by the pianist and composer Percy Grainger.

Pletnev: Concert suite from The Nutcracker, for solo piano

The pianist and conductor Mikhail Pletnev adapted some of the music into a virtuosic concert suite for piano solo:

- March

- Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy

- Tarantella

- Intermezzo (Journey through the Snow)

- Russian Trepak

- Chinese Dance

- Andante maestoso (Pas de Deux)

Contemporary arrangements

- In 1942, Freddy Martin and his orchestra recorded The Nutcracker Suite for Dance Orchestra on a set of 4 10-inch 78-RPM records issued by RCA Victor. An arrangement of the suite that lay between dance music and jazz.[49]

- In 1947, Fred Waring and His Pennsylvanians recorded "The Nutcracker Suite" on a two-part Decca Records 12-inch 78 RPM record with one part on each side as Decca DU 90022,[50] packaged in a picture sleeve. This version had custom lyrics written for Waring's chorus by, among others, Waring himself. The arrangements were by Harry Simeone.

- In 1952, the Les Brown big band recorded a version of the Nutcracker Suite, arranged by Frank Comstock, for Coral Records.[51] Brown rerecorded the arrangement in stereo for his 1958 Capitol Records album Concert Modern.

- In 1960, Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn composed jazz interpretations of pieces from Tchaikovsky's score, recorded and released on LP as The Nutcracker Suite.[52] In 1999, this suite was supplemented with additional arrangements from the score by David Berger for The Harlem Nutcracker, a production of the ballet by choreographer Donald Byrd (born 1949) set during the Harlem Renaissance.[53]

- In 1960, Shorty Rogers released The Swingin' Nutcracker, featuring jazz interpretations of pieces from Tchaikovsky's score.

- In 1962, American poet and humorist Ogden Nash wrote verses inspired by the ballet,[54] and these verses have sometimes been performed in concert versions of the Nutcracker Suite. It has been recorded with Peter Ustinov reciting the verses, and the music is unchanged from the original.[55]

- In 1962 a novelty boogie piano arrangement of the "Marche", titled "Nut Rocker", was a No. 1 single in the UK, and No. 21 in the US. Credited to B. Bumble and the Stingers, it was produced by Kim Fowley and featured studio musicians Al Hazan (piano), Earl Palmer (drums), Tommy Tedesco (guitar) and Red Callender (bass). "Nut Rocker" has subsequently been covered by many others including The Shadows, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, The Ventures, Dropkick Murphys, The Brian Setzer Orchestra, and the Trans-Siberian Orchestra. The Ventures' own instrumental rock cover of "Nut Rocker", known as "Nutty", is commonly connected to the NHL team, the Boston Bruins, from being used as the theme for the Bruins' telecast games for over two decades, from the late 1960s. In 2004, The Invincible Czars arranged, recorded, and now annually perform the entire suite for rock band.

- The Trans-Siberian Orchestra's first album, Christmas Eve and Other Stories, includes an instrumental piece titled "A Mad Russian's Christmas", which is a rock version of music from The Nutcracker.

- On the other end of the scale is the comedic version by Spike Jones and his City Slickers released by RCA Victor in December 1945 as "Spike Jones presents for the Kiddies: The Nutcracker Suite (With Apologies to Tchaikovsky)", featuring humorous lyrics by Foster Carling and additional music by Joe "Country" Washburne. An abridged and resequenced version of this recording was issued in 1971 on the LP album Spike Jones is Murdering the Classics, one of the rare comedic pop records to be issued on the prestigious RCA Red Seal label.

- International choreographer Val Caniparoli has created several versions of The Nutcracker ballet for Louisville Ballet, Cincinnati Ballet, Royal New Zealand Ballet, and Grand Rapids Ballet.[56] While his ballets remain classically rooted, he has contemporarized them with changes such as making Marie an adult instead of a child, or having Drosselmeir emerges through the clock face during the overture making "him more humorous and mischievous."[57] Caniparoli has been influenced by his simultaneous career as a dancer, having joined San Francisco Ballet in 1971 and performing as Drosselmeir and other various Nutcracker roles ever since that time.[58]

- The Disco Biscuits, a trance-fusion jam band from Philadelphia, have performed "Waltz of the Flowers" and "Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy" on multiple occasions.

- The Los Angeles Guitar Quartet (LAGQ) recorded the Suite arranged for four acoustic guitars on their CD recording Dances from Renaissance to Nutcracker (1992, Delos).

- In 1993, guitarist Tim Sparks recorded his arrangements for acoustic guitar on The Nutcracker Suite.

- The Shirim Klezmer Orchestra released a klezmer version, titled "Klezmer Nutcracker", in 1998 on the Newport label. The album became the basis for a December 2008 production by Ellen Kushner, titled The Klezmer Nutcracker and staged off-Broadway in New York City.[59]

- In 2002, The Constructus Corporation used the melody of Sugar Plum Fairy for their track "Choose Your Own Adventure".

- In 2009, Pet Shop Boys used a melody from "March" for their track "All Over the World", taken from their album Yes.

- In 2012, jazz pianist Eyran Katsenelenbogen released his renditions of Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy, Dance of the Reed Flutes, Russian Dance and Waltz of the Flowers from the Nutcracker Suite.

- In 2014, Pentatonix released an a cappella arrangement of "Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy" on the holiday album That's Christmas to Me and received a Grammy Award on 16 February 2016 for best arrangement.

- In 2016, Jennifer Thomas included an instrumental version of "Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy" on her album Winter Symphony.

- In 2017, Lindsey Stirling released her version of "Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy" on her holiday album Warmer in the Winter.[60]

- In 2018, Pentatonix released an a cappella arrangement of "Waltz of the Flowers" on the holiday album Christmas Is Here!.

- In 2019, Madonna sampled a portion on her song "Dark Ballet" from her Madame X album.[61]

- In 2019, Mariah Carey released a normal and an a cappella version of "Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy" entitled the "Sugar Plum Fairy Introlude" to open and close her 25th Deluxe Anniversary Edition of Merry Christmas.[62]

- In 2020, Coone made a hardstyle cover version titled "The Nutcracker".[63]

Remove ads

Selected discography

Summarize

Perspective

The Nutcracker made its initial appearance on disc in 1909 in an abridged performance on the Odeon label. Historically, this 4-disc set is considered to be the first record album.[64] The recording was conducted by Herman Finck and featured the London Palace Orchestra.[65] It was not until after the modern LP record appeared in 1948 that recordings of the complete ballet began to be made. Because of the ballet's approximate ninety minute length when performed without intermission, applause, or interpolated numbers, the music requires two LPs. Most CD issues of the music take up two discs, often with fillers. An exception is the 81-minute 1998 Philips recording by Valery Gergiev that fits onto one CD because of Gergiev's somewhat brisker tempi.

- In 1954, the first complete recording of the ballet was released on two LPs by Mercury Records. The cover design was by George Maas with illustrations by Dorothy Maas.[66] The music was performed by the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Antal Doráti. Doráti later re-recorded the complete ballet in stereo, with the London Symphony Orchestra in 1962 for Mercury and with the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra in 1975 for Philips Classics. According to Mercury Records, the 1962 recording was made on 35mm magnetic film rather than audio tape, and used album cover art identical to that of the 1954 recording.[67][68] Doráti is the only conductor so far to have made three different recordings of the complete ballet. Some critics have cited the 1975 recording as the finest ever made of the complete ballet.[69] It is also faithful to the score in employing a boys' choir in the Waltz of the Snowflakes. Many other recordings use an adult or mixed choir.

- In 1956, Artur Rodziński and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra made a complete recording of the ballet in stereo for Westminster Records.

- In 1959, the first stereo LP album set of the complete ballet, with Ernest Ansermet conducting the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, appeared on Decca Records in the UK and London Records in the US.

- The first complete stereo Nutcracker with a Russian conductor and a Russian orchestra appeared in 1960, when Gennady Rozhdestvensky's recording with the Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra, was issued first in the Soviet Union on the Melodiya label, then imported to the U.S. by Columbia Masterworks. It was also Columbia Masterworks' first complete Nutcracker.[70]

With the advent of the stereo LP coinciding with the growing popularity of the complete ballet, many other complete recordings have been made. Notable conductors who have done so include Maurice Abravanel, André Previn, Michael Tilson Thomas, Mariss Jansons, Seiji Ozawa, Richard Bonynge, Semyon Bychkov, Alexander Vedernikov, Ondrej Lenard, Mikhail Pletnev, and Simon Rattle.[71][72]

- The soundtrack of the 1977 television production with Mikhail Baryshnikov and Gelsey Kirkland, featuring the National Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Kenneth Schermerhorn, was issued in stereo on a Columbia Masterworks 2 LP-set, but has not appeared on CD. The LP soundtrack recording was, for a time, the only stereo version of the Baryshnikov Nutcracker available, since the performance was originally telecast in monophonic sound. The DVD of the performance is in stereo.

- The first complete recording of the ballet in digital stereo was issued in 1985, by RCA Red Seal featuring Leonard Slatkin conducting the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra. RCA later reissued the recording in a multi-CD set containing complete recordings of Tchaikovsky's two other ballets, Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty.

There have been two major theatrical film versions of the ballet, and both have corresponding soundtrack albums.

- The first theatrical film adaptation, made in 1985, is of the Pacific Northwest Ballet version, and was conducted by Sir Charles Mackerras. The music is played in this production by the London Symphony Orchestra. The film was directed by Carroll Ballard, who had never before directed a ballet film (and has not done so since). Patricia Barker played Clara in the fantasy sequences, and Vanessa Sharp played her in the Christmas party scene. Wade Walthall was the Nutcracker Prince.

- The second film adaptation was a 1993 film of the New York City Ballet version, titled George Balanchine's The Nutcracker, with David Zinman conducting the New York City Ballet Orchestra. The director was Emile Ardolino, who had won the Emmy, Obie, and Academy Awards for filming dance, and was to die of AIDS later that year. Principal dancers included the Balanchine muse Darci Kistler, who played the Sugar Plum Fairy, Heather Watts, Damian Woetzel, and Kyra Nichols. Two well-known actors also took part: Macaulay Culkin appeared as the Nutcracker/Prince, and Kevin Kline served as the offscreen narrator. The soundtrack features the interpolated number from The Sleeping Beauty that Balanchine used in the production, and the music is heard on the album in the order that it appears in the film, not in the order that it appears in the original ballet.[73]

- Notable albums of excerpts from the ballet, rather than just the usual Nutcracker Suite, were recorded by Eugene Ormandy conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra for Columbia Masterworks, and Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for RCA Victor. Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops Orchestra (for RCA Victor), as well as Erich Kunzel and the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra (for Telarc) have also recorded albums of extended excerpts. The original issue of Michael Tilson Thomas's version with the Philharmonia Orchestra on CBS Masterworks was complete.[74] the currently available edition is abridged.[75]

Ormandy, Reiner and Fiedler never recorded a complete version of the ballet; however, Kunzel's album of excerpts runs 73 minutes, containing more than two-thirds of the music. Conductor Neeme Järvi has recorded act 2 of the ballet complete, along with excerpts from Swan Lake. The music is played by the Royal Scottish National Orchestra.[76]

- Many famous conductors of the twentieth century made recordings of the suite, but not of the complete ballet. These include Arturo Toscanini, Sir Thomas Beecham, Claudio Abbado, Leonard Bernstein, Herbert von Karajan, James Levine, Sir Neville Marriner, Robert Shaw, Mstislav Rostropovich, Sir Georg Solti, Leopold Stokowski, Zubin Mehta, and John Williams.

- In 2007, Josh Perschbacher recorded an organ transcription of the Nutcracker Suite.

Remove ads

Ethnic stereotypes and cultural misattribution

Summarize

Perspective

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (December 2023) |

In the United States, commentary emerged in the 2010s about the Chinese and Arabian characteristic dances. In a 2014 article titled "Sorry, 'The Nutcracker' Is Racist", writer Alice Robb panned the typical choreography of the Chinese dance as white people wearing "harem pants and a straw hat, eyes painted to look slanted" and "wearing chopsticks in their black wigs"; the Arabian dance, she said, has a woman who "slinks around the stage in a belly shirt, bells attached to her ankles".[77] Similarly, dance professor Jennifer Fisher at the University of California, Irvine, complained in 2018 about the use in the Chinese dance of "bobbing, subservient 'kowtow' steps, Fu Manchu mustaches, and, especially, the often-used saffron-tinged makeup, widely known as 'yellowface.'"[78] In 2013, Dance Magazine printed the opinions of three directors: Ronald Alexander of Steps on Broadway and The Harlem School of the Arts said the characters in some of the dances were "borderline caricatures, if not downright demeaning", and that some productions had made changes to improve this; Stoner Winslett of the Richmond Ballet said The Nutcracker was not racist and that her productions had a "diverse cast"; and Donald Byrd of Spectrum Dance Theater saw the ballet as Eurocentric and not racist.[79] Some people who have performed in productions of the ballet do not see a problem because they are continuing what is viewed as "a tradition".[77] According to George Balanchine, the Arabian dance was a sensuous belly dance intended for the fathers, not the children.[80]

Among the attempts to change the dances in the United States were Austin McCormick making the Arabian dance into a pole dance, and San Francisco Ballet and Pittsburgh Ballet Theater changing the Chinese dance to a dragon dance.[77] Georgina Pazcoguin of the New York City Ballet and former dancer Phil Chan started the "Final Bow for Yellowface" movement and created a web site which explained the history of the practices and suggested changes. One of their points was that only the Chinese dance made dancers look like an ethnic group other than the one they belonged to. The New York City Ballet went on to drop geisha wigs and makeup and change some dance moves. Some other ballet companies followed.[78]

The Nutcracker's "Arabian" dance is in fact an embellished, exotified version of a traditional Georgian lullaby, with no genuine connection to the Arab culture.[81] Alastair Macaulay of The New York Times defended Tchaikovsky, saying he "never intended his Chinese and Arabian music to be ethnographically correct".[82] He said, "their extraordinary color and energy are far from condescending, and they make the world of 'The Nutcracker' larger."[82] To change anything is to "unbalance The Nutcracker" with music the author did not write. If there were stereotypes, Tchaikovsky also used them in representing his own country of Russia.[82]

Remove ads

In popular culture

Summarize

Perspective

Film

Several films having little or nothing to do with the ballet or the original Hoffmann tale have used its music:

- The 1940 Disney animated film Fantasia features a segment using The Nutcracker Suite.[83]

- A 1951 thirty-minute short, Santa and the Fairy Snow Queen features several dances from The Nutcracker.[84]

- In 1986, Nutcracker: The Motion Picture was released. It was a collaboration between the Pacific Northwest Ballet and illustrator Maurice Sendak.

- Barbie in the Nutcracker (2001) was based on the ballet.

- In 2007, Tom and Jerry: A Nutcracker Tale was released featuring Tchaikovsky's music from the ballet as score.

- In 2010, The Nutcracker in 3D with Elle Fanning abandoned the ballet and most of the story, retaining much of Tchaikovsky's music with lyrics by Tim Rice. The $90 million film became the year's biggest box office bomb.

- In 2017, the Athens State Orchestra presented "A Different Nutcracker" animation film, directed by Yiorgos Molvalis.[85]

- In 2018, the Disney live-action film The Nutcracker and the Four Realms was released with Lasse Hallström and Joe Johnston as directors and a script by Ashleigh Powell.[86][87]

- The 2022 Russian-Hungarian animated film The Nutcracker and the Magic Flute adapted the story and used the music, while combining them with other classical works.[88]

Television

- The 1987 true crime miniseries Nutcracker: Money, Madness and Murder, opens every episode with the first notes of the ballet amid scenes of Frances Schreuder's daughter dancing to it in ballet dress.[89]

- The 2015 Canadian television film The Curse of Clara: A Holiday Tale, based on an autobiographical short story by onetime Canadian ballet student Vickie Fagan, centres on a young ballet student preparing to dance the role of Clara in a production of The Nutcracker.[90]

Children's recordings

There have been several recorded children's adaptations of the E. T. A. Hoffmann story (the basis for the ballet) using Tchaikovsky's music, some quite faithful, some not. One that was not was a version titled The Nutcracker Suite for Children, narrated by Metropolitan Opera announcer Milton Cross, which used a two-piano arrangement of the music. It was released as a 78-RPM album set in the 1940s. A later version, titled The Nutcracker Suite, starred Denise Bryer and a full cast, was released in the 1960s on LP and made use of Tchaikovsky's music in the original orchestral arrangements. It was quite faithful to Hoffmann's story The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, on which the ballet is based, even to the point of including the section in which Clara cuts her arm on the glass toy cabinet, and also mentioning that she married the Prince at the end. It also included a less gruesome version of "The Tale of the Hard Nut", the tale-within-a-tale in Hoffmann's story. It was released as part of the Tale Spinners for Children series.[91]

Spike Jones produced a 78 rpm record set "Spike Jones presents for the kiddies The Nutcracker Suite (with Apologies to Tchaikovsky)" in 1944. It includes the tracks: "The Little Girl's Dream", "Land of the Sugar Plum Fairy", "The Fairy Ball", "The Mysterious Room", "Back to the Fairy Ball" and "End of the Little Girl's Dream". This is all done in typical Spike Jones style, with the addition of choruses and some swing music. The entire recording is available at archive.com[92]

Journalism

- In 2009, Pulitzer Prize–winning dance critic Sarah Kaufman wrote a series of articles for The Washington Post criticizing the primacy of The Nutcracker in the American repertory for stunting the creative evolution of ballet in the United States:[93][94][95]

That warm and welcoming veneer of domestic bliss in The Nutcracker gives the appearance that all is just plummy in the ballet world. But ballet is beset by serious ailments that threaten its future in this country... companies are so cautious in their programming that they have effectively reduced an art form to a rotation of over-roasted chestnuts that no one can justifiably croon about... The tyranny of The Nutcracker is emblematic of how dull and risk-averse American ballet has become. There were moments throughout the 20th century when ballet was brave. When it threw bold punches at its own conventions. First among these was the Ballets Russes period, when ballet—ballet—lassoed the avant-garde art movement and, with works such as Michel Fokine's fashionably sexy Scheherazade (1910) and Léonide Massine's Cubist-inspired Parade (1917), made world capitals sit up and take notice. Afraid of scandal? Not these free-thinkers; Vaslav Nijinsky's rough-hewn, aggressive Rite of Spring famously put Paris in an uproar in 1913... Where are this century's provocations? Has ballet become so entwined with its "Nutcracker" image, so fearfully wedded to unthreatening offerings, that it has forgotten how eye-opening and ultimately nourishing creative destruction can be?[94]

— Sarah Kaufman, dance critic for The Washington Post

- In 2010, Alastair Macaulay, dance critic for The New York Times (who had previously taken Kaufman to task for her criticism of The Nutcracker[96]) began The Nutcracker Chronicles, a series of blog articles documenting his travels across the United States to see different productions of the ballet.[97]

Act I of The Nutcracker ends with snow falling and snowflakes dancing. Yet The Nutcracker is now seasonal entertainment even in parts of America where snow seldom falls: Hawaii, the California coast, Florida. Over the last 70 years this ballet—conceived in the Old World—has become an American institution. Its amalgam of children, parents, toys, a Christmas tree, snow, sweets and Tchaikovsky's astounding score is integral to the season of good will that runs from Thanksgiving to New Year... I am a European who lives in America, and I never saw any Nutcracker until I was 21. Since then I've seen it many times. The importance of this ballet to America has become a phenomenon that surely says as much about this country as it does about this work of art. So this year I'm running a Nutcracker marathon: taking in as many different American productions as I can reasonably manage in November and December, from coast to coast (more than 20, if all goes well). America is a country I'm still discovering; let The Nutcracker be part of my research.[98]

— Alastair Macaulay, dance critic for The New York Times

- In 2014, Ellen O'Connell, who trained with the Royal Ballet in London, wrote, in Salon (website), on the darker side of The Nutcracker story. In E. T. A. Hoffmann's original story, the Nutcracker and Mouse King, Marie's (Clara's), journey becomes a fevered delirium that transports her to a land where she sees sparkling Christmas Forests and Marzipan Castles, but in a world populated with dolls.[99] Hoffmann's tales were so bizarre, Sigmund Freud wrote about them in The Uncanny.[100][101]

E. T. A. Hoffmann's 1816 fairy tale, on which the ballet is based, is troubling: Marie, a young girl, falls in love with a nutcracker doll, whom she only sees come alive when she falls asleep. ...Marie falls, ostensibly in a fevered dream, into a glass cabinet, cutting her arm badly. She hears stories of trickery, deceit, a rodent mother avenging her children's death, and a character who must never fall asleep (but of course does, with disastrous consequences). While she heals from her wound, the mouse king brainwashes her in her sleep. Her family forbids her from speaking of her "dreams" anymore, but when she vows to love even an ugly nutcracker, he comes alive and she marries him.

— Ellen O'Connell-Whittet, Lecturer, University of California, Santa Barbara Writing Program

Popular music

- The song "Dance Mystique" (track B1) on the studio album Bach to the Blues (1964) by the Ramsey Lewis Trio is a jazz adaptation of Coffee (Arabian Dance).

- The song "Fall Out" by English band Mansun from their 1998 album Six heavily relies on the celesta theme from the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy.

- The song "Dark Ballet" by American singer-songwriter Madonna samples the melody of Dance of the Reed Flutes (Danish Marzipan) which is often mistaken for Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy. The song also relied on the lesser-known harp cadenza from Waltz of the Flowers. The same Tchaikovsky sample was earlier used in internationally famous 1992 ads for Cadbury Dairy Milk Fruit & Nut with 'Madonna' as the singing chocolate bar (in Russian version the subtitles "'This Is Madonna'" (Russian: Это Мадонна, romanized: Eto Madonna) were displayed on a screen).[102]

Video games

- Waltz of the Flowers is played in one chapter of What Remains of Edith Finch.

- The official Nintendo published version of Tetris for the Nintendo Entertainment System, as well as the Game Boy Advance version of Tetris Worlds features Dance of the Suger Plum Fairy as one of their music options, and the Game Boy version uses Trepak as victory music for clearing 25 lines on Type B level 9.

- Waltz of the Flowers is played in a combat section of Fort Frolic in BioShock.

- The Nutcracker Suite is played during the Symphony of Sorcery level in Kingdom Hearts: Dream Drop Distance.

See also

Notes

- Щелкунчикъ in Russian pre-revolutionary orthography spelling

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads