Maria Tallchief

American ballerina (1925–2013) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Maria Tallchief, born Elizabeth Marie Tall Chief (𐓏𐒰𐓐𐒿𐒷-𐓍𐓂͘𐓄𐒰 "Two-Standards"; Osage family name: Ki He Kah Stah Tsa, Osage script: 𐒼𐒱𐒹𐒻𐒼𐒰-𐓆𐓈𐒷𐓊𐒷; January 24, 1925 – April 11, 2013), was an Osage and American ballerina. She was America's first major prima ballerina and the first Native American to hold the rank. Together with Georgian-American choreographer George Balanchine, she is widely considered to have revolutionized American ballet.[1][2][3][4]

Maria Tallchief 𐓏𐒰𐓐𐒿𐒷-𐓍𐓂͘𐓄𐒰 | |

|---|---|

Tallchief in 1961 | |

| Born | Elizabeth Marie Tall Chief January 24, 1925 Fairfax, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Died | April 11, 2013 (aged 88) |

| Occupation | Prima ballerina |

| Years active | 1942–1966 |

| Height | 5 ft 9 in (1.75 m)[1] |

| Spouses | Elmourza Natirboff

(m. 1952; div. 1954)Henry D. Paschen Jr.

(m. 1956; died 2004) |

| Children | Elise Paschen |

| Career | |

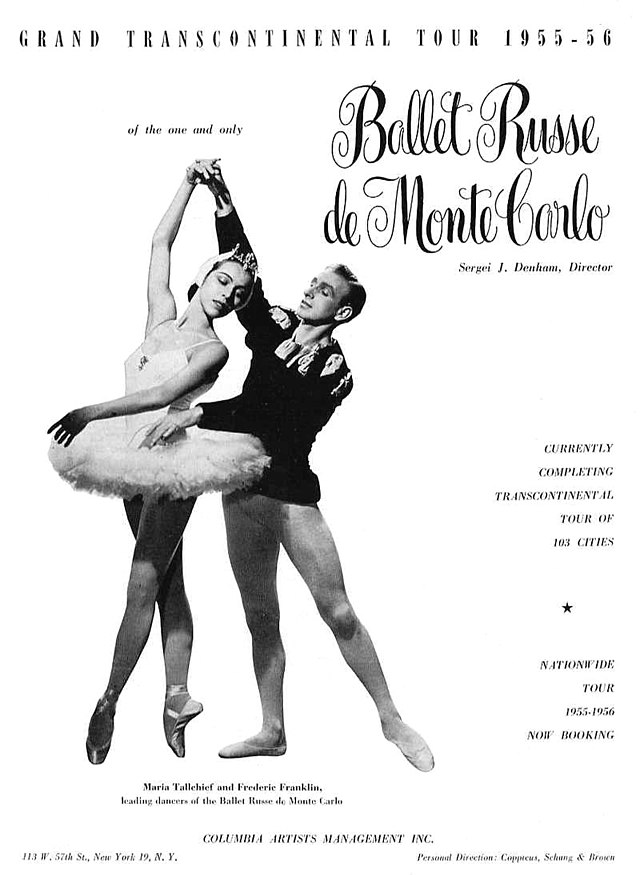

| Former groups | Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo New York City Ballet |

| Dances |

|

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Elizabeth Marie Tall Chief was born in Fairfax, Oklahoma, on January 24, 1925, as the third child of Alexander Joseph Tall Chief (1890–1959), a member of the Osage Nation, and his second wife, Ruth (née Porter), of Scottish-Irish descent.[5][6] Porter had met Alexander Tall Chief, then a widower, while visiting her sister, who was his mother's housekeeper at the time.[5] Elizabeth Marie was known as "Betty Marie" to friends and family.

Elizabeth Tall Chief's paternal great-grandfather, Peter Bigheart, had helped negotiate for the Osage concerning rights to mineral and other resources of their reservation land. When oil was discovered, oil revenues enriched members of the Osage Nation. Her father grew up with wealth, never working "a day in his life."[6]

In her autobiography, Tallchief explained, "As a young girl growing up on the Osage reservation in Fairfax, Oklahoma, I felt my father owned the town. He had property everywhere. The local movie theater on Main Street and the pool hall opposite belonged to him. Our 10-room, a terracotta-brick house stood high on a hill overlooking the reservation." The family spent summers in Colorado Springs to escape the Oklahoma heat. Life was far from perfect, though, as her father was a binge drinker and her parents often fought about money.[6]

Tallchief's father had first been married to a German immigrant and had three children from that marriage before her death: Alex III; Frances (1913–1999); and Thomas (1919–1981). Thomas played football for the University of Oklahoma, and was drafted by the Pittsburgh Steelers.

Alexander and Ruth Tall Chef first child was a boy, Gerald (1922–1999). He was severely injured in childhood when kicked in the head by a horse and never regained normal cognitive function.[6][7] Their second, Marjorie, became an accomplished ballerina in her own right. She also was Tallchief's "best friend."[6]

As a child, Ruth Porter had dreamed about becoming a performer, but her family could not afford dance or music lessons.[4] She was determined that her daughters would have opportunities for both. Marjorie and Betty Marie were enrolled in summer ballet classes in Colorado Springs, the latter starting at age 3. She and other family members also performed at rodeos and other local events.[4] Betty Marie studied piano and contemplated becoming a concert pianist.[5]

In 1930, a ballet teacher from Tulsa, Mrs. Sabin, visited Fairfax looking for students and took on Betty Marie and Marjorie as students. Looking back on Sabin many years later, Tallchief wrote, "She was a wretched instructor who never taught the basics, and it's a miracle I wasn't permanently harmed."[6] In addition to the problems in her teaching technique, Sabin had put Betty Marie en pointe shortly after she joined the school (at 5 years old), when she was far too young to be able to dance en pointe without injury.[8]

At age five, Betty Marie was enrolled at the nearby Sacred Heart Catholic School. Impressed by her reading ability, the teachers allowed her to skip the first two grade levels. Between piano, ballet, and school work, she had little free time but loved the outdoors. In her autobiography, she reminisced about time spent "wandering around our big front yard" and "[rambling] around the grounds of our summer cottage hunting for arrowheads in the grass."[6]

In 1933, the family moved to Los Angeles with the intent of getting the children into Hollywood musicals.[4] The day they arrived in Los Angeles, her mother asked the clerk at a local drugstore if he knew any good dance teachers. The clerk recommended Ernest Belcher, father of dancer Marge Champion. "An anonymous man in an unfamiliar town decided our fate with those few words," Tallchief later recalled.[5] The California school moved Betty Marie back to the proper grade for her age but put her in an Opportunity Class for advanced learners. "Opportunity Class or not, I was still way ahead," she recalled. "With nothing to do, I often wandered around the schoolyard by myself."[6] At this time in ballet class, Betty Marie was removed from pointe, probably saving her from major injury.[8]

Bored with school, Betty Marie devoted herself to dance in Belcher's studio. In addition to ballet, which she had to relearn from the beginning, she also studied tap, Spanish dancing, and acrobatics. She found tumbling very difficult and eventually quit the class, but later in life put the skills to good use. The family moved to Beverly Hills, where schools offered better academics. At Beverly Vista School, Betty Marie experienced what she described as "painful" discrimination and took to spelling her last name as one word, Tallchief.[6] She continued to study piano, appearing as a guest soloist with small symphony orchestras throughout high school.[3]

At age 12, Tallchief began to work with Bronislava Nijinska, a renowned choreographer who had recently opened her own studio in Los Angeles, and David Lichine, a choreographer and former dancer.[5][9] Nijinska "was a personification of what ballet was all about," Tallchief recalled. "I looked at her, and I knew this was what I wanted to do."[4] Nijinska imparted a strong sense of discipline and the belief that being a ballerina was a full-time task. "We didn't concentrate only for an hour and a half a day," Tallchief recalled. "We lived it."[6] It was under Nijinska that Tallchief decided ballet was what she wanted to devote her life to. "Before Nijinska, I liked ballet but believed that I was destined to become a concert pianist," she recalled. "Now my goal was different." Nijinska saw Tallchief was serious and began devoting great attention to her.[6]

When Tallchief was 15, Nijinska decided to stage three ballets in the Hollywood Bowl. Tallchief expected a lead role but instead was put in the corps de ballet. She was devastated: "I was hurt and humiliated. I couldn't understand what was happening ... Didn't she love me anymore?"[6] After a pep talk from her mother, Tallchief rededicated herself and soon worked her way into a lead part in Chopin Concerto.[6][10] When the big day came, she slipped during rehearsal and was concerned, but Nijinska dismissed it saying "happens to everybody."[6][10] Tallchief also received instruction from various distinguished teachers during their visits to Los Angeles.[5] For Ada Broadbent, she danced her first pas de deux. Mia Slavenska took a shine to Tallchief and arranged for her to audition for Serge Denham, director of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. He was impressed, but nothing came of it.[6]

Career

Summarize

Perspective

Early career

Tallchief graduated from Beverly Hills High School in 1942.[10] She had given up piano and wanted to go to college, but her father was against it. "I've paid for your lessons all your life," he said. "Now it's time for you to find a job."[6] She won a bit part in Presenting Lily Mars, an MGM musical with Judy Garland. Dancing in the movie was "not gratifying" and Tallchief decided against making a career of it.[6] That summer, family friend Tatiana Riabouchinska asked if Tallchief would like to go to New York City.[10] With Riabouchinska chaperoning, she set off for the city at age 17 in 1942.[5]

Once in New York, Tallchief looked up Denham, for whom she had an earlier favorable audition. A secretary told her that his Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo did not need any more dancers, and she left crying. A few days later, she was told there was a place for her after all.[11] Denham did not remember her, but she had something he needed – a passport. Many of his dancers were Russian refugee émigrés who were stateless and lacked passports. The troupe had an upcoming Canadian tour. She was taken on, but only as an apprentice.[10][9] Her performance was in Gaîté Parisienne.[11] After the Canadian tour, one dancer left the troupe. Maria Tallchief was offered that dancer's place at $40 per week.[11]

On her first day as a full member of the company, Tallchief was surprised to find that her former teacher, Nijinska, had come to town to stage Chopin Concerto with the company. She soon cast Tallchief as first ballerina Nathalie Krassovska's understudy for the lead role.[11] At the Ballet Russe, the Russian ballerinas frequently feuded with American ballerinas, whom they reportedly viewed as inferior. When Tallchief was surprisingly promoted by Nijinska, she became the primary target of their animosity.[11][4]

At the same time, the company was preparing to stage Agnes de Mille's Rodeo, or The Courting at Burnt Ranch, an early example of balletic Americana.[5] One day, de Mille suggested that Tallchief change her name. It was a sensitive subject for Tallchief; Denham had previously suggested Tallchief change her surname to a Russian-sounding name such as Tallchieva, a practice common among ballet dancers at the time. She refused: "Tallchief was my name, and I was proud of it."[11] However, de Mille had a more acceptable idea – using a modified version of her middle name. Tallchief agreed and was known as Maria Tallchief for the remainder of her career.[11]

Within her first two months at Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, Tallchief had appeared in seven different ballets as part of the corps de ballet.[11] While in New York, she took classes at the School of American Ballet, but on tour there were no official classes.[11][12] Instead, Tallchief studied the efforts of her more experienced colleagues. In particular, she admired Alexandra Danilova, who was known for her work ethic and professionalism. Tallchief practiced whenever she could, earning a reputation as a hard worker. "I was always doing a barre," she wrote, "always giving it my all in rehearsals."[11]

Krassovska feuded with management regularly, raising the possibility of a sudden promotion for Tallchief. Krassovska nearly quit the company late in 1942, and Tallchief was told she would go on in her place. Krassovska was persuaded to return, but the incident made it clear to Tallchief she needed to be ready to perform Krassovska's technically difficult role on short notice – something for which she was not yet ready. In the spring of 1943, Krassovska argued with Denham and left the company. "Unprepared, I was numb with terror," Tallchief recalled.[11] When the company returned to New York, Tallchief received positive reviews. The New York Times dance critic John Martin wrote, "Tallchief gave a stunning account of herself in Nijinkska's Chopin Concerto ... She has an easy brilliance that smacks of authority rather than bravura," and predicted she would be a big star in the near future. Glory, however, was short-lived as Tallchief returned to the corps when the staging of Chopin Concerto was complete.[11]

Back on tour, Tallchief saw her parents in Los Angeles. Seeing Tallchief's frail appearance – she had lost a lot of weight from a combination of poor nutrition and stress – and her minor role in The Snow Maiden, her mother, Ruth, attempted to persuade Tallchief to quit ballet and return to piano. Ruth changed her mind when Lichine showed her Martin's column and explained that he was America's top dance critic.[13] Tallchief's second year with Ballet Russe brought bigger roles. She was a soloist in Le Beau Danube and got the lead in Ancient Russia, another Nijinska ballet.[11]

Balanchine era

In the spring of 1944, well-known choreographer George Balanchine was hired by Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo to work on a new production called Song of Norway.[11] This was a catalyst in Tallchief's and Balanchine's careers. She was drawn to Balanchine from the start. Describing one of her first experiences with him, she wrote, "When I saw what he had done, I was astonished. Everything seemed so simple yet perfect: An elegant ballet fell into place before my eyes."[4] At first, she was not sure if he was paying much attention to her, but she quickly found out he was. Balanchine assigned Tallchief a solo in Song of Norway and on the night before the premiere, also told her that she would be Danilova's understudy.[12] The ballet was a success and Balanchine was offered a contract for the rest of the season. He was glad to get back into ballet after years on Broadway and in Hollywood, and accepted the offer.[12] Sensing Tallchief's star was on the rise, her mother demanded a raise for her daughter. Tallchief was "mortified" by her action, but Denham gave in to the demands and increased the dancer's salary to $50 per week and promoted her to "soloist."[12]

Balanchine continued to cast Tallchief in important roles, featuring her in a pas de trois with Mary Ellen Moylan and Nicholas Magallanes in Danses Concertantes. The steps were classical in form, but were presented in a unique manner. Tallchief wrote: "The accent was sharp, the rhythm swinging and modern," and, "Performing the steps seemed more like an exercise for pleasure and enjoyment than work. It was magical." In Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, she had a pas de deux with Yurek Lazowsky.[12]

Shortly before Ballet Imperial was to open, Balanchine told Tallchief that she would be second lead behind Moylan. "I nearly fainted," she recalled. "I couldn't get over it."[12] As the season wore on, Balanchine grew fond of her both professionally – The Washington Post called Tallchief his "crucial artistic inspiration" – and personally.[4] Tallchief was ignorant of the personal attraction for a long time and their relationship remained mostly on a professional level.[12] Slowly they became friends; then one day, Balanchine asked Tallchief to marry him, much to her surprise. After some thought, she agreed and the couple wed on August 16, 1946.[5]

One night on tour in 1945, Tallchief was doing her barre when Balanchine remarked, "If only you would learn to do battement tendu properly you wouldn't have to learn anything else."[12] It was his way of saying she needed to start all over – battement tendu is the most basic ballet exercise there is. "I wanted to die," she recalled. "But I had seen the difference between Mary Ellen's [who was a pupil of Balanchine] dancing and mine. I knew he was right."[12] Under the tutelage of Balanchine, Tallchief lost ten pounds and elongated her legs and neck.[10][12] She learned how to hold her chest high, keep her back straight, and keep her feet arched.[10] "My body seemed to be going through a metamorphosis," she recalled. Tallchief relearned the basic exercises the way Balanchine wanted and transformed her greatest weakness—turnout—into a strength. Danilova devoted a lot of her time to instructing Tallchief in the ballerina's art, helping her transform from a teenage girl into a young woman.[12]

Tallchief rose to the rank of "featured soloist" as Balanchine continued to cast her in important roles.[2] She was the first person to perform the role of Coquette in Night Shadow, the ballet's most technically challenging role, after Danilova selected the other female lead for herself.[3][12]

New York City Ballet

In 1946, Balanchine joined with arts patron Lincoln Kirstein to establish the Ballet Society, a direct forerunner to the New York City Ballet.[5] Tallchief had six months remaining on her contract with Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, so she stayed with the company until 1947.[3][14] When her contract expired, she joined Balanchine, who was in France as guest choreographer at the Paris Opera Ballet. He had been called upon to "save" the famous troupe, but not everyone appreciated his presence. He ignored the company's hierarchy, further angering some dancers.[14] A group of supporters of Serge Lifar, who was on leave while accusations of aiding the Nazis during World War II were investigated, led a vocal campaign to get rid of Balanchine. Spectateur and Les Arts joined in, publishing articles attacking Balanchine personally.[14]

Upon her arrival in France, Tallchief was put to work immediately with roles in Le baiser de la fée and Apollo. Another dancer pulled out of Apollo shortly before opening night, forcing Tallchief to learn a more difficult role on short notice.[14] In spite of all the difficulties, opening night was a huge success. The French press was fascinated by Tallchief's dancing, and even more so her background. "Peau Rouge danse a l'Opera pour le Roi de Suede" [Redskin dances at the Opera for the King of Sweden], read a front-page headline.[14] "La Fille du grand chef Indien danse a l'Opera" [The daughter of the great Indian chief dances at the Opera], read another.[14] Her colleagues never appreciated Tallchief, but French audiences loved her.[4] After six months in Paris, Tallchief and Balanchine returned to New York.[14] During her time in Paris, Tallchief became the first American to perform with the Paris Opera Ballet.[4]

When the couple returned to the States, Tallchief quickly became one of the first stars, and the first prima ballerina, of the New York City Ballet, which opened in October 1948.[1][5] Balanchine "revolutionized ballet" by creating roles that demanded athleticism, speed, and aggressive dancing like nothing before. Tallchief was well suited for Balanchine's vision. "I always thought Balanchine was more of a musician even than a choreographer, and perhaps that's why he and I connected," Tallchief recalled.[4] He created many roles specifically for Tallchief, including the lead of "The Firebird" in 1949.[5] Of her "Firebird" debut, Kirstein wrote, "Maria Tallchief made an electrifying appearance, emerging as the nearest approximation to a prima ballerina that we had yet enjoyed."[15] The role created a sensation and launched her to the top of the ballet world, granting her the prima ballerina title.[1][9] Noting the great technical difficulty of the role, The New York Times critic John Martin wrote that Tallchief was asked "to do everything except spin on her head, and she does it with complete and incomparable brilliance."[4]

Tallchief's popularity helped the fledgling dance company grow and she was asked to perform as many as eight times a week.[15] Although Balanchine and Tallchief ended their marriage in 1951, they continued to work together.

In 1954, Tallchief was given the role of Sugar Plum Fairy in Balanchine's newly reworked version of The Nutcracker, then an obscure ballet. Her performance of the role helped transform the work into an annual Christmas classic, and the industry's most reliable box-office draw.[4] Critic Walter Terry remarked, "Maria Tallchief, as the Sugar Plum Fairy, is herself a creature of magic, dancing the seemingly impossible with effortless beauty of movement, electrifying us with her brilliance, enchanting us with her radiance of being. Does she have any equals anywhere, inside or outside of fairyland? While watching her in The Nutcracker, one is tempted to doubt it."[15]

Other notable roles Tallchief created under Balanchine include the Swan Queen in Balanchine's version of Swan Lake and Eurydice in Orpheus.[5] She created the lead role of "Prodigal Son," "Jones Beach," "A La Françaix, and plotless works such as "Sylvia Pas de Deux," "Allegro Brillante, "Pas de Dix, and "Symphony in C."[3] Her fiery, athletic performances helped establish Balanchine as the era's most prominent and influential choreographer.[4]

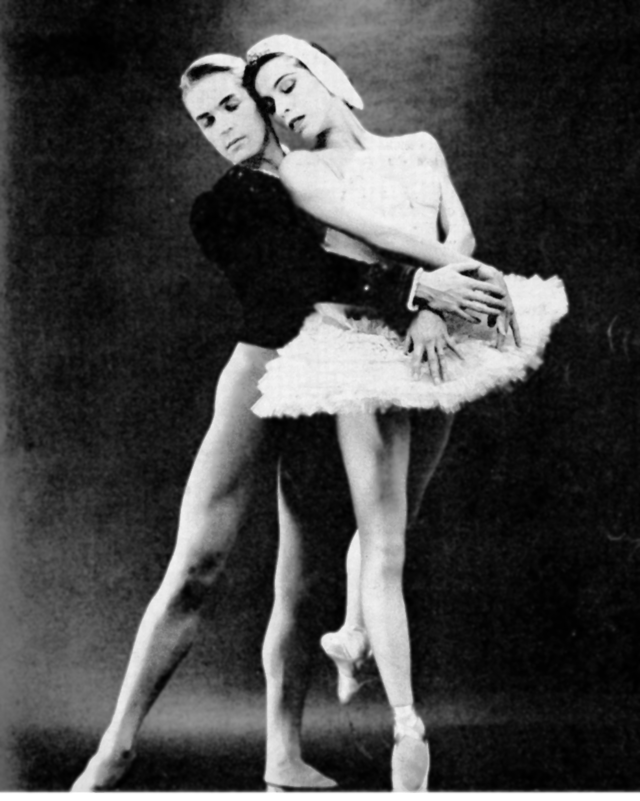

Tallchief remained with the New York City Ballet until February 1960, but also took time off to work with other companies.[3] She made guest appearances with the Chicago Opera Ballet, the San Francisco Ballet, the Royal Danish Ballet, and the Hamburg Ballet, among others. Working for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in 1954–55, she was paid $2,000 a week, reportedly the highest salary ever paid to a dancer at the time.[5] In 1958, she created the lead in Balanchine's Gounod Symphony before taking a leave of absence to have her first child.[15]

Later career

After leaving the New York City Ballet, Tallchief joined American Ballet Theatre, first as a guest dancer then as prima ballerina.[3] That summer, she appeared alongside Danish danseur Erik Bruhn in Russia, where she was recognized for "aplomb, brilliance, and dignity of the American style."[3][4] In so doing, she became the first American dancer to perform at Moscow's famed Bolshoi Theater.[4] From 1960 to 1962, Tallchief expanded her repertoire taking on dramatic, as opposed to abstract, roles such as the title roles of Birgit Cullberg's Miss Julie and Lady from the Sea, as well as the melancholy heroine of Antony Tudor's Jardin aux Lilas.[3][5]

Tallchief's dancing was not confined to the stage. She appeared on multiple TV shows, including The Ed Sullivan Show.[4] She portrayed Anna Pavlova in the 1952 movie musical Million Dollar Mermaid.[5] In 1962, Tallchief was Rudolf Nureyev's partner of choice for his American debut, which was broadcast on national television.[15] Her final performance in America was on television's "Bell Telephone Hour" in 1966.[10]

On the urging of Balanchine (to whom she was no longer married), she relocated to Germany, briefly becoming the lead dancer of the Hamburg Ballet.[10] One of her last performances was a 1966 title role in Peter van Dyk's Cinderella, before she retired from dancing,[5] not wishing to dance beyond her prime.[10][15] During her career, she danced throughout Europe and South America, Japan, and Russia.[10] She made guest appearances with several symphony orchestras.[3]

Teaching and administration

After retiring from dancing, Tallchief moved to Chicago, where her husband Buzz Paschen resided.[10] She served as director of ballet for the Lyric Opera of Chicago from 1973 to 1979.[2] In 1974, she founded Lyric Opera's ballet school, where she taught the Balanchine technique.[5][4] Explaining her teaching philosophy, she wrote "New ideas are essential, but we must retain respect for the art of ballet–and that means the artist too–or else it is no longer an art form."[15]

With her sister Marjorie, Tallchief founded the Chicago City Ballet in 1981.[9] She served as co-artistic director until its demise in 1987.[10] Despite the company failing, the Chicago Tribune called her "a force in the history of Chicago dance," and said she arguably increased the popularity of dance in the city.[10]

Tallchief was featured in the documentary film Dancing for Mr. B in 1989. From 1990 until her death, she was artistic adviser to Von Heidecke's Chicago Festival Ballet.[9]

Dance style

Summarize

Perspective

Tallchief was known for "dazzling audiences with her speed, energy and fire."[5] She was said to exhibit both "electrifying passion" and great technical ability.[4] She combined precise footwork with athleticism.[4] Ashley Wheater, artistic director of the Joffrey Ballet, remarked, "When you watch Tallchief on video, you see that aside from the technical polish there is a burning passion she brought to her dancing. In her interpretation of Balanchine's "Firebird," she was consumed both inside and out. She was not just a great dancer, but a real artist—a true interpreter who brought her personality to bear on the dancing."[2] According to Time, she was also "a master in the perfect pause, the moment of stillness allowing the audience and the narrative to keep pace with the choreography."[1]

William Mason, director emeritus of the Lyric Opera of Chicago, described Tallchief as "a consummate professional ... She realized who and what she was, but she didn't flaunt it. She was unpretentious."[10] Fellow dancer Allegra Kent remarked "She didn't seem to be frightened of the stage, like some of the others. She had an iron will inside ... She phrased her curls and extensions as delicately or as strongly as the music itself."[1]

Personal life

Summarize

Perspective

During her first year at the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, Tallchief dated Russian dancer Alexander "Sasha" Goudevitch, the darling of the company. "For both of us, it was our first love," Tallchief recalled. "We saw each other every day, and I was convinced it was true love."[11] Goudevitch moonlighted for extra money and bought Tallchief an engagement ring. In the spring of 1944, however, he had a sudden change of heart when another young woman began to pursue him. As Tallchief later recalled, "My heart was broken."[11]

After Georgian-American ballet choreographer George Balanchine was hired by the Ballet Russe, he found himself attracted to Tallchief both professionally and personally. She was unaware he felt this way: "It never occurred to me that there was anything more than dancing on his mind ... It would have been preposterous to think there was anything personal."[12] Although their relationship became more intimate, it was a shock to Tallchief when Balanchine asked her to marry him. During the summer of 1945, he invited her to meet him after a Los Angeles performance. Balanchine opened the car door for her, and when she got in, he sat in silence for a moment before saying, "Maria, I would like you to become my wife,"[12] "I almost fell out of my seat and was unable to respond," she recalled.[12] She eventually replied, "But, George, I'm not sure I love you. I feel I hardly know you."[12] He answered that it did not matter, and if the marriage only lasted a few years, that was all right with him. After a day to think it over, Tallchief accepted his proposal.[12]

When she told her parents about the engagement, her mother was furious: "I've never heard of anything more ... idiotic [...] What's wrong with you?"[12] Balanchine was unshaken by her objection, saying she would come around eventually. While they were engaged, Balanchine made extravagant romantic gestures and treated Tallchief with great affection. "He was obviously trying to convince me [that our marriage] was inevitable," she wrote. "I didn't need convincing. I was falling in love."[12]

Tallchief and Balanchine were married on August 16, 1946, when she was 21 years old and he was 42.[5][4] Her parents continued to oppose the marriage and did not attend the ceremony.[14] The couple did not have a traditional honeymoon: "For both of us, work was more important."[14]

According to Tallchief, "Passion and romance didn't play a big part in our married life. We saved our emotions for the classroom." Nonetheless, she described Balanchine as "a warm, affectionate, loving husband."[5] Their marriage was annulled in 1952, when both parties were attracted to other people.[4]

In 1952, Tallchief married Elmourza Natirboff, a pilot for a private charter airline. The couple divorced two years later.[5][4] In 1955, she met Chicago businessman Henry D. ("Buzz") Paschen Jr.[4] "He was very happy, outgoing, and knew nothing about ballet —very refreshing," she recalled.[10] The couple married the following June and honeymooned with a ballet tour of Europe.[10] With Paschen, Tallchief had her only child, Elise Maria Paschen (born 1959), who became an award-winning poet and executive director of the Poetry Society of America. With this marriage, Tallchief also gained a stepdaughter, Margaret Wright.[16] The couple remained together, even through Paschen's brief imprisonment for tax evasion, until his death, in 2004.[10]

Tallchief tended to be direct in expressing her opinion, never mincing words. "It gave her the illusion of being a diva," said Tallchief protégé Kenneth von Heidecke, "but it was really a keen sense of honesty."[10]

Death and legacy

Summarize

Perspective

In December 2012, Tallchief broke her hip. She died on April 11, 2013, from complications stemming from the injury.[4]

Tallchief was considered America's first major prima ballerina and was the first Native American to hold the rank.[2][5] She remained closely tied to her Osage history until her death, speaking out against stereotypes and misconceptions about Native Americans on many occasions.[5] Tallchief was involved with America for Indian Opportunity and was a director of the Indian Council Fire Achievement Award.[9] She and her sister Marjorie were two of five Native American ballet dancers from Oklahoma born in the 1920s. However, she wished to be judged on the merits of her dance alone. "Above all, I wanted to be appreciated as a prima ballerina who happened to be a Native American, never as someone who was an American Indian ballerina," she wrote.[4]

Tallchief was called "one of the most brilliant American ballerinas of the 20th century" by The New York Times.[5] According to Wheater, she "paved the way for dancers who were not in the traditional mold of ballet ... she was crucial in breaking the stigma."[2] Upon Tallchief's death, Jacques d'Amboise remarked "When you thought of Russian ballet, it was Ulanova. With English ballet, it was Fonteyn. For American ballet, it was Tallchief. She was grand in the grandest way."[5] Time remarked "of all the ballerinas of the last century, few achieved Maria Tallchief's artistry, a kind of conscious dreaming, a reverie with backbone."[1]

She is credited with "[breaking] down ethnic barriers" and was among the first Americans to flourish in a field long dominated by Russians and Europeans.[4] Reflecting on her own career, Tallchief wrote "I was in the middle of magic, in the presence of genius. And thank God I knew it."[4]

Honors

In Oklahoma, Tallchief was honored by the governor for both her ballet achievements and her pride in her American Indian heritage. The Legislature declared June 29, 1953, as "Maria Tallchief Day."[9] She stands among four other Indian ballerinas depicted in "Flight of Spirit," a mural in the Oklahoma Capitol building.[9] Tallchief is a subject of one of the life-size bronze statues titled The Five Moons, located at the Tulsa Historical Society. Osage Nation honored her with the title "Princess Wa-Xthe-Thomba" (Osage: 𐓏𐓘𐓸𐓧𐓟-𐓵𐓪͘𐓬𐓘, romanized: Wahle-ðǫpa, "Woman of Two Worlds" or "Two Standards").[17][9] In 1996, Tallchief received a Kennedy Center Honor for lifetime achievements. Her Kennedy Center biography states that Tallchief was "both the inspiration and the living expression of the best [the United States] has given the world. Her individualism and her genius came together to create one of the most vital and beautiful chapters in the history of American dance."[15]

Tallchief is an inductee of the National Women's Hall of Fame, and was twice named "Woman of the Year" by the Washington Press Club.[5][9] She twice was on Dance Magazine's annual award list.[9] The magazine explained the 1960 recognition: "[Tallchief is a] star with a truly American flavor, whose qualities of elegance, brilliance, and modesty ... [made] a distinguished contribution to the recent cultural mission of American Ballet Theatre in Europe and Russia."[3] In 1999, Tallchief was awarded the American National Medal of Arts by the National Endowment of the Arts; in 2011, she received the Chicago History Museum's Making History Award for Distinction in the Performing Arts.[18]

In 2006, the Metropolitan Museum of Art presented a special tribute to Maria Tallchief titled "A Tribute to Ballet Great Maria Tallchief," during which Tallchief officially named Kenneth von Heidecke as her protégé.[19]

In 2018, Tallchief became one of the inductees in the first induction ceremony held by the National Native American Hall of Fame.[20]

On November 13, 2020, a Google Doodle was made in honor of her.[21]

Tallchief is presently being honored on an American Women quarter.[22] The quarter, designed by Benjamin Sowards and sculpted by Joseph Menna, shows her on the reverse side opposite a depiction of George Washington sculpted by Laura Gardin Fraser.[17] She also appears on the 2023 redesign of the "Sacagawea dollar".[23][24]

- Tallchief is depicted and honored on the 2023 American Women quarter

- Tallchief and the Five Moons are honored on the 2023 Native American dollar

Biographies and documentaries

Tallchief has been the subject of multiple biographies. Her autobiography, Maria Tallchief: America's Prima Ballerina, was co-written with Larry Kaplan and released in 1997.[9]

Sandy and Yasu Osawa of Upstream Productions in Seattle, Washington, made a documentary titled Maria Tallchief in November 2007 that aired on PBS between 2007 and 2010.

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.