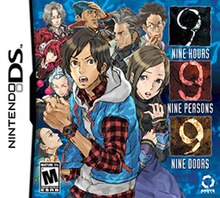

999: Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors

2009 video game From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

999: Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors[b] is a visual novel and adventure video game developed by Chunsoft. It is the first installment in the Zero Escape series, and was released in Japan in December 2009 and in North America in November 2010 for the Nintendo DS. The story follows Junpei, a college student who is abducted along with eight other people and forced to play the "Nonary Game", which puts its participants in a life-or-death situation, to escape from a sinking cruise liner. The gameplay alternates between two types of sections: Escape sections, where the player completes puzzles in escape-the-room scenarios; and Novel sections, where the player reads the game's narrative and makes decisions that influence the story toward one of six different endings.

| 999: Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors | |

|---|---|

North American first-print cover art, featuring the main characters | |

| Developer(s) | Chunsoft |

| Publisher(s) | |

| Director(s) | Kotaro Uchikoshi |

| Producer(s) | Jiro Ishii |

| Artist(s) | Kinu Nishimura |

| Writer(s) | Kotaro Uchikoshi |

| Composer(s) | Shinji Hosoe |

| Series | Zero Escape |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | December 10, 2009

|

| Genre(s) | Adventure, visual novel, escape the room |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Development of the game began after Kotaro Uchikoshi joined Chunsoft to write a visual novel for them that could reach a wider audience; Uchikoshi suggested adding puzzle elements that are integrated with the game's story. The inspiration for the story was the question of where inspiration comes from; while researching it, Uchikoshi came across Rupert Sheldrake's morphic resonance hypothesis, which became the main focus of the game's science fiction elements. The music was composed by Shinji Hosoe, while the characters were designed by Kinu Nishimura. The localization was handled by Aksys Games; they worked by the philosophy of keeping true to the spirit of the original Japanese version, aiming for natural-sounding English rather than following the original's exact wording.

999 was positively received, with reviewers praising the story, writing and puzzles, but criticizing the game's tone and trial-and-error gameplay. While the Japanese release was a commercial failure, the game sold better than expected for the genre in the United States. Although 999 was developed as a stand-alone title, its unexpected critical success in North America prompted the continuation of the series.

The sequel, Zero Escape: Virtue's Last Reward, was released in 2012, which was followed by Zero Time Dilemma, released in 2016. An updated version of 999, with voice acting and higher resolution graphics, was released alongside a port of Virtue's Last Reward as part of the Zero Escape: The Nonary Games. This bundle was released for PlayStation 4, PlayStation Vita, and Microsoft Windows via Steam in March 2017, and for Xbox One in March 2022.

Gameplay

Summarize

Perspective

999 is an adventure game in which the player assumes the role of a college student named Junpei.[2] The gameplay is divided into two types of sections: Novel and Escape. In the Novel sections, the player progresses through the branching storyline and converses with non-playable characters through visual novel segments.[3] These sections require little interaction from the player as they are spent reading the text that appears on the screen, which represents either dialogue between the various characters or Junpei's thoughts.[4] During Novel sections, the player will sometimes be presented with decision options that affect the course of the game,[5] resulting in one of six endings.[6] The whole plot is not revealed in just one playthrough; the player needs to reach the "true" ending to get all the information behind the mystery,[7] which in turn requires another specific ending to be reached beforehand.[8] Some endings contain hints to how to reach further endings.[7]

In between Novel sections are Escape sections, which occur when the player finds themselves in a room from which they need to find the means of escape.[7] These are presented from a first-person perspective, with the player being able to move between different pre-determined positions in each room.[4] To escape, the player is tasked with finding various items and solving puzzles, reminiscent of escape-the-room games.[3] At some points, the player may need to combine objects with each other to create the necessary tool to complete a puzzle.[6] The puzzles include various brain teasers, such as baccarat and magic squares.[4][5] An in-game calculator is provided for math-related problems,[6] and the player can ask characters for hints if they find an Escape room too difficult.[9] All Escape sections are self-contained, with all items required to solve the puzzles being available within that section; items are not carried over between Escape sections.[5] After finishing an Escape section, it becomes available to replay from the game's main menu.[6]

Plot

Summarize

Perspective

Characters and setting

999 features nine main characters, who are forced to participate in the Nonary Game by an unknown person code-named Zero.[2] For the majority of the game, the characters adopt code names to protect their identities due to the stakes of the Nonary Game—most of their names are ultimately revealed over the course of the game, and for several their true identities are important to the plot.[10] The player-controlled Junpei is joined by June, a nervous girl and a childhood friend of Junpei whom he knows as Akane Kurashiki; Lotus, a self-serving woman with unknown skills; Seven, a large and muscular man; Santa, a fashionable punk with a negative attitude; Ace, an older and wiser man; Snake, a blind man with a princely demeanor; Clover, a girl prone to mood swings and Snake's younger sister; and the 9th Man, a fidgety individual.[11]

The events of the game occur within a cruise ship, though all of the external doors and windows have been sealed, and many of the internal doors are locked.[10] The game's nine characters learn that they have been kidnapped and brought to the ship to play the Nonary Game, with the challenge to find the door marked with a "9" within nine hours before the ship sinks.[12] To do this, they are forced to work in separate teams to make their way through the ship and solve puzzles to find this door.[3] This is set in part by special locks on numbered doors that are based on digital roots; each player has a bracelet with a different digit on it, and only groups of three to five with the total of their bracelet's number with the same digital root as marked on the door can pass through.[10]

Story

Junpei escapes a flooding cabin after waking up, wearing a bracelet displaying the number "5". He encounters the eight other passengers. Zero announces over a loudspeaker that all nine are participants in the Nonary Game, explains the rules, and states each carry an explosive in their stomach that will go off if they try to bypass the digital root door locks. Trying to escape on his own, the 9th man threatens Clover, and is able to coerce Ace and her to scan their bracelets on Door 5's keypad. It is then revealed that it is not only necessary for all of the entrants to scan their bracelets at the entrance, but everyone who scanned must also authenticate within the rooms behind the Doors as well—lest the bombs of everyone who entered explode. Fearing what harm might come to them, the group adopts code names and splits up to explore the ship. Over the course of the story, Snake and an unknown man are found dead. The player has the option to select which group that Junpei travels with, which affects the story; several choices lead to Junpei and the cast's death at the hands of either Ace or Clover. Through various choices, Junpei learns of a previous Nonary Game, played nine years earlier, and the connections of the other characters through that, as well as studies about morphic resonance and stories of the Egyptian priestess Alice, who is frozen in ice-nine.[10]

In one ending, Clover is found dead. Junpei learns that the dead man was not Snake and that the first Nonary Game was run by Cradle Pharmaceutical, of which Ace is the CEO. Zero was a participant of this game, and had set up the second Nonary Game as revenge towards Ace. The surviving players confront Ace and deduce he killed every person found dead in order to both cover his identity and obtain their bracelets. Ace holds Lotus hostage and escapes. As they find Snake and the door with the 9, Akane becomes weak. Santa watches over her while the others enter the door, leading to an incinerator where Ace and Lotus are. Learning of his sister's murder, Snake tackles Ace, and the others pull Junpei out of the incinerator before it activates, consuming Snake and Ace. Junpei returns to Akane, finding her nearly dead. Zero claims over the loudspeakers that he has lost. Junpei investigates a nearby room, and returns to find Akane and Santa have disappeared, after which he is knocked out by a gas grenade.[10] After the player views this ending, they can then access the "true" ending.

In the true ending, Junpei learns that the previous Nonary Game consisted of nine pairs of kidnapped siblings separated onto the ocean-bound Gigantic and in a mock-up in Building Q in a Nevada desert. The game was designed to explore morphic fields; the research anticipated that the stress of the game would activate the fields between siblings, allowing solutions solved by one to be sent via these fields to their counterpart at the other location. This research was to help Ace cure his prosopagnosia. This Nonary Game went awry: Akane and her brother Santa were placed at the same location instead of being separated, and Seven discovered the kidnappings and rescued the children from the ship. Ace grabbed Akane before she could escape, forced her into the incinerator room, and started the incinerator while leaving a puzzle for her escape. Unable to solve the puzzle, Akane was apparently burnt to death while the other children, including Snake and Lotus's daughters, escaped with Seven.[10]

After rescuing Snake, Junpei and the others reach the incinerator; Akane disappears and Santa escapes while taking Ace hostage, trapping the others inside. It is then revealed that the portion of the game's narrative portrayed on the bottom screen of the Nintendo DS, which only shows narration and interacts with puzzles, is presented from a 12-year-old Akane's point of view during the first Nonary Game.[c] Through morphic fields, she connected to Junpei in the future, witnessing several possible endings and directing Junpei to help him survive. Junpei then faces the same puzzle Akane did, and relays the solution back to Akane in the past, allowing her to escape with Seven and the other children. Junpei realizes that Akane was Zero and, with assistance from Santa, had recreated the game and all the events she had witnessed in order to ensure her survival and avoid a temporal paradox. As Junpei and the others escape, they discover that the game had taken place in Building Q the entire time; Akane and Santa have fled, leaving behind a car with Ace restrained in the trunk. In the game's epilogue, they drive away hoping to catch up with them and pick up a hitchhiker in Egyptian robes.[10]

Development

Summarize

Perspective

999 was developed by the Japanese game studio Chunsoft and directed by Kotaro Uchikoshi,[13] and produced by Jiro Ishii.[14] Chunsoft had made successful visual novels in the past, such as Kamaitachi no Yoru (1994), but wanted to create a new type of visual novel that could be received by a wider audience;[13] they contacted Uchikoshi, who at the time was working on a mobile game based on Kamaitachi no Yoru, and asked him to serve as a writer for the then upcoming visual novel 428: Shibuya Scramble. Uchikoshi did not join the company in time to work on 428, but came up with the idea to include puzzles that are integrated within a story, and need to be solved for the player to make progress: he enjoyed playing browser-based escape-the-room games, but thought that they would be more interesting if they had a larger focus on telling a story.[14] This idea served as the basis for 999, and Uchikoshi was named director of the project.[13][14]

Development of 999 began in 2008.[15] The inspiration for the story was the question "where do mankind's inspirations come from?"; Uchikoshi researched it, and found the British author Rupert Sheldrake's theories of morphogenetic fields, which became the main theme of the game. The theory is similar to telepathy, which answers the question of how organisms are able to simultaneously communicate ideas to each other, without physical or social interaction. Uchikoshi used the theory to develop the concept of esper characters, which are able to either transmit or receive information from another individual. Because of the vital role of the number 9 in the plot, each of the characters was based on one of the nine personality types from the Enneagram of Personality.[16] Another source of inspiration was Kamaitachi no Yoru, which, like 999, begins with putting the characters in a state of discomfort.[17]

Uchikoshi started writing the script by working on the ending first. From there, he would continue to work backwards, in order to not get confused when writing the plot.[18] The game's setting, with characters who are trapped and try to escape, was meant to embody two of humanity's instinctive desires: the unconscious desire to return to one's mother's womb and shut oneself away, and the desire to escape and overcome one's current condition. This was a theme Uchikoshi had used before, when writing the visual novel Ever 17: The Out of Infinity (2002).[16] The illustrations by character designer Kinu Nishimura influenced the script, as certain scenes were altered to match the character illustrations.[14] Among scrapped story elements were the use of hands as a major part of the story; in the final stages of production, Uchikoshi's higher-ups did not accept this focus, forcing him to re-write the story. The characters were originally supposed to be handcuffed to each other as they try to escape, but the idea was scrapped as it was seen as overused, with appearances in light novels such as Mahou Shoujo Riska (2004).[19]

The Escape sequences were created to appeal to players' innate desires: Uchikoshi wanted them to feel the instinctive pleasure that he described as "I found it!".[16] For the puzzles, he would consider the details within the story, and the props and gimmicks found in the game; after deciding on them, they were integrated with the puzzles.[18] He also used puzzle websites as reference.[16] He did not design the puzzles himself, instead leaving the puzzle direction to other staff, while checking it multiple times.[20]

Shinji Hosoe, the president of the game music production company SuperSweep, was chosen to compose the game's soundtrack for being skilled in a wide range of music genres, ensuring that he could compose music that would fit a lot of different types of moods and scenes. He described his work on the game as the most straightforward music project he had had, due to receiving concise reference material that answered all his questions about the game; he made a few test tracks, after which everything went smoothly. The music was written using the Nintendo DS's internal synth, and Hosoe worked together with fellow SuperSweep composer Yousuke Yasui to make this less obvious.[21]

Localization

The North American localization of the game was handled by Aksys Games; Chunsoft was introduced to Aksys by Spike while looking for a company that could publish the game in North America. When Aksys evaluated 999, many at the company did not believe in its commercial viability and at first turned it down; as many of the people who evaluate games at Aksys do not speak Japanese, it was difficult for them to gauge whether a game was good or not. In the end they decided to localize it, which was considered a big risk for the company.[22]

The localization was done by the philosophy of keeping true to the spirit of the original Japanese, making dialogue sound like what a native speaker of English would say instead of strictly adhering the original's exact wording. The localization editor, Ben Bateman, did this by looking at the writing from a wider view, line by line or scene by scene rather than word by word or sentence by sentence, and thinking about how to convey the same ideas in English. Most parts of the game that include a joke in the localization also have a joke in the Japanese version, but a different one; Bateman did however try to make similar types of jokes, with similar contents and ideas.[22] The game's use of Japanese language puns led to problems, as many of them relied on Japanese dialects to function; for these, Bateman replaced them with new puns in English.[23] He was given mostly free rein in what he could change or add, as long as it did not disrupt the plot.[22]

During the localization, Bateman had to keep track of the numerous plot points throughout the game, as the script had not been written in chronological order due to the numerous endings.[23] Localizing the game took roughly two months. Another challenge was getting the localization done in time: Nobara Nakayama, the game's translator, worked on it for 30 days, and the editing process took two months. Because of this, Bateman had to do most of the work "on the fly". Nakayama had started playing the game prior to starting work on the localization, but did not finish playing it until she was more than halfway through translating it; after learning that the plot hinged on a Japanese pun, they had to halt the localization to discuss it with Uchikoshi and come up with a solution, after which they went through the whole game to make sure that it still made sense.[22] Another problem Bateman ran into was related to the game's first person narration. A plot twist regarding the narration relied on the use of gender-specific first person pronouns at specific points in the story. As this would not work in English, the narration was made to instead be in the third person, and the twist's effect was replicated by shifting from third to first person at a specific story point. Bateman admits however that the twist is "more mindblowing in Japanese".[24]

During a scene related to an abstract painting of a dog, one of the localized answers for what the painting depicts is "Funyarinpa", a nonsense word directly translated from the original Japanese game. Picking it prompts a humorous exchange between Junpei and Lotus. This became a highly popular meme within Zero Escape circles.[25][26]

Release

Summarize

Perspective

999 was originally released in Japan by Spike on December 10, 2009, for the Nintendo DS.[1] An American release followed on November 16, 2010.[27] In the United States, a replica of the in-game bracelets was included with pre-orders at GameStop;[28] due to low pre-orders, Aksys made these available on their website's shop, both separately and bundled with the game.[29] Upon release, 999 became the eleventh and ultimately final Nintendo DS game to be rated M by the ESRB.[30][31] It was a commercial failure in Japan,[32] with 27,762 copies sold in 2009 and an additional 11,891 in 2010, reaching a total of 39,653 copies sold.[33][34] Meanwhile, American sales were described as being strong; according to Uchikoshi, this was a surprise, as the visual novel genre was seen as being particular to Japan and unlikely to be accepted overseas.[35]

In addition to the game, other 999 media was released. The game's soundtrack was published by SuperSweep on December 23, 2009.[36] A novelization of the game, Kyokugen Dasshutsu 9 Jikan 9 Nin 9 no Tobira Alterna,[d] was written by Kenji Kuroda and released by Kodansha in 2010 in two volumes, titled Jou and Ge.[e][37][38] Coinciding with the release of the game's sequel, Zero Escape: Virtue's Last Reward (2012), 999 was reprinted under the title Zero Escape: Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors, with new box art featuring the Zero Escape brand.[39]

An iOS version of the game, 999: The Novel, was developed by Spike Chunsoft as the second entry in their Smart Sound Novel series. It was released in Japan on May 29, 2013,[40] and worldwide in English on March 17, 2014. This version lacks the Escape sections of the Nintendo DS version, and features high resolution graphics and an added flowchart that helps players keep track of which narrative paths they have experienced; additionally, dialogue is presented through speech bubbles,[41][42] and an extra ending is included.[43] This version has since been removed from the App Store.[44]

Zero Escape: The Nonary Games, a bundle that contains remastered versions of 999 and Virtue's Last Reward, was released for Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 4 and PlayStation Vita in the West on March 24, 2017.[45] People who purchased the Windows version through Steam in its first week of release received a complimentary soundtrack, with songs from 999 and Virtue's Last Reward.[46] In Japan, the Microsoft Windows version launched on March 25 and the console versions on April 13.[47][43] The European PlayStation Vita version was released on December 15.[48] The Nonary Games was later released for Xbox One on March 22, 2022, and was added to the Xbox Game Pass service for console, PC and cloud on the same date.[49] The 999 remaster retained most of the features from The Novel, but the new ending was not included.[43]

Reception

Summarize

Perspective

| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | 82/100[50] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Destructoid | 10/10[6] |

| Eurogamer | 7/10[51] |

| Famitsu | 36/40[1] |

| GameSpot | 8.5/10[4] |

| GamesRadar+ | 4.5/5[52] |

| IGN | 9/10[3] |

| Nintendo Life | 8/10[9] |

| Nintendo World Report | 9/10[7] |

| The Escapist | 4/5[5] |

| Wired | 8/10[12] |

Reception

999 was well received by critics, according to the review aggregator Metacritic.[50] Polygon included it on a list of the best games of all time, crediting it with popularizing the visual novel genre in America.[53]

Reviewers enjoyed the writing and narrative,[3][6][7][52] with Andy Goergen of Nintendo World Report labeling it as "a strong argument for video games as a new medium of storytelling".[7] Reviewers at Famitsu called the story enigmatic and thrilling.[1] Carolyn Petit at GameSpot felt that the lengthy Novel sections amplified the fear and tension throughout the game,[4] while Heidi Kemps of GamesRadar compared them to "high-quality thriller novels".[52] Jason Schreier of Wired criticized the prose for being inconsistent, but said that the use of the narrator was clever and unusual.[12] Susan Arendt at The Escapist called the story multi-layered and horrifying.[5] Zach Kaplan at Nintendo Life liked the dialogue, but found the third-person narration to be dull and slow, with out-of-place or clichéd metaphors and similes.[9] Both Chris Schilling at Eurogamer and Lucas M. Thomas at IGN felt that the urgency portrayed in the game's story sometimes was at odds with the tone or timing of the dialogue, such as lengthy conversations while trapped inside a freezer, or lighthearted dialogue and jokes.[3][51] Thomas called the premise gripping, and said that the mythology, conspiracies and character backgrounds were engrossing.[3] Tony Ponce at Destructoid said that the characters initially seemed like a "stock anime cast", but that the player discovers more complexity in them after moving past first impressions.[6] Kaplan felt that each character was well developed, fleshed out and unique, and could pass for real people.[9]

A Famitsu writer said that they enjoyed solving puzzles, and that it gave them a sense of accomplishment;[1] similarly, Goergen, Petit, Schilling and Arendt called the puzzles satisfying to solve.[4][5][7][51] Goergen found some puzzles to be cleverly done, but said that some were esoteric.[7] Ponce and Petit liked that the puzzles never became "pixel hunts", and how everything is visible as long as the player looks carefully;[4][6] because of this and the lack of red herrings, time limits and dead ends, Ponce found it to be better than other escape-the-room games. He applauded the large amount of content, saying that even someone only buying the game for the puzzles would be satisfied.[6] Schilling and Thomas appreciated the puzzles, but found some solutions and hints to be too obvious or explanatory.[3][51] Kemps found the puzzles excellently done and challenging, but disliked how difficult it was to reach the true ending.[52] Kemps and Schreier appreciated how the puzzles felt logical, while they, along with Thomas and Arendt, criticized how the player has to re-do puzzle sequences upon subsequent playthroughs.[3][5][52][12] Goergen, Schreier, Thomas and Arendt all appreciated the fast-forward function, as it made repeated playthroughs more bearable,[3][5][7][12] but Thomas felt that it didn't go far enough in speeding up the process.[3]

Goergen found the sound designs to be unmemorable, saying that the music does not add much and that players would be likely to mute the game after hearing the "beeping" sound effect used for dialogue for too long.[7] Meanwhile, Ponce and Petit liked it:[4][6] Ponce called the score "masterful" and said that it "gets under your skin at the right moments",[6] while Petit said that she appreciated the sound, which she called atmospheric and "[sending] shivers up your spine". She was unimpressed with the environments, but said that they were clear and easy to look at. She liked the character portraits, calling them expressive and, paired with the dialogue, enough to make the player not care about the lack of voice acting.[4] Ponce, too, felt that the game did not need voice acting. He felt that the way the game favored textual narration over animated cutscenes made it more immersive, allowing the player to imagine the scenes.[6] Goergen said that the graphics were well done, but that they did not do much for the atmosphere.[7] Kaplan called the presentation "awesome", saying that it looked great and that the artwork stood on its own despite the simplicity of the animations, and that the soundtrack was "fantastic".[9]

999 received some awards from gaming publications, including: Best Story of 2010 from IGN,[54] Best Graphic Adventure of 2010 on a Handheld System from RPGFan,[55] and an Editor's Choice Award from Destructoid.[6] Bob Mackey at 1UP.com featured 999 on a list of "must-play" Nintendo DS visual novels, citing its story, themes and "zany narrative experimentation",[56] and Jason Schreier at Kotaku included it on a list of "must-play" visual novels worth playing even for people who do not like anime tropes.[57] RPGFan listed it as one of the thirty essential role-playing video games from the years 2010 to 2015.[58]

Sequels

999 is the first game in the Zero Escape series, and was originally intended to be a stand-alone game. The development for the sequel began after the first game got positive reviews.[18] Zero Escape: Virtue's Last Reward, the successor to 999,[59] was developed by Chunsoft for the Nintendo 3DS and PlayStation Vita, and was first released on February 16, 2012, in Japan,[60] and later that year in North America and Europe.[61][62] Virtue's Last Reward also follows a group of nine people,[63] and focuses on game theory, specifically the prisoner's dilemma.[64] Zero Time Dilemma, released in 2016, is set between the events of the previous two games,[65] and has morality as its main theme.[66]

Notes

- Known in Japan as Kyokugen Dasshutsu 9 Jikan 9 Nin 9 no Tobira (極限脱出 9時間9人9の扉, "Extreme Escape: 9 Hours, 9 Persons, 9 Doors").[1]

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.