Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Nimrud

Ancient Assyrian city From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Nimrud (/nɪmˈruːd/; Syriac: ܢܢܡܪܕ Arabic: النمرود) is an ancient Assyrian city (original Assyrian name Kalḫu, biblical name Calah) located in Iraq, 30 kilometres (20 mi) south of the city of Mosul, and 5 kilometres (3 mi) south of the village of Selamiyah (Arabic: السلامية), in the Nineveh Plains in Upper Mesopotamia. It was a major Assyrian city between approximately 1350 BC and 610 BC. The city is located in a strategic position 10 kilometres (6 mi) north of the point that the river Tigris meets its tributary the Great Zab.[1] The city covered an area of 360 hectares (890 acres).[2] The ruins of the city were found within one kilometre (1,100 yd) of the modern-day Assyrian village of Noomanea in Nineveh Governorate, Iraq.

Remove ads

The name Nimrud was recorded as the local name by Carsten Niebuhr in the mid-18th century.[3][note 1] In the mid 19th century, biblical archaeologists proposed the Assyrian name Kalḫu (the Biblical Calah), based on a description of the travels of Nimrod in Genesis 10.[note 2]

Archaeological excavations at the site began in 1845, and were conducted at intervals between then and 1879, and then from 1949 onwards. Many important pieces were discovered, with most being moved to museums in Iraq and abroad. In 2013, the UK's Arts and Humanities Research Council funded the "Nimrud Project", directed by Eleanor Robson, whose aims were to write the history of the city in ancient and modern times, to identify and record the dispersal history of artefacts from Nimrud,[4] distributed amongst at least 76 museums worldwide (including 36 in the United States and 13 in the United Kingdom).[5]

In 2015, the terrorist organization Islamic State announced its intention to destroy the site because of its "un-Islamic" Assyrian nature. In March 2015, the Iraqi government reported that Islamic State had used bulldozers to destroy excavated remains of the city. Several videos released by ISIL showed the work in progress. In November 2016, Iraqi forces retook the site, and later visitors also confirmed that around 90% of the excavated portion of city had been completely destroyed. The ruins of Nimrud have remained guarded by Iraqi forces ever since.[6] Reconstruction work is in progress.

Remove ads

Early history

Summarize

Perspective

Foundation

Kalhu was located on a prosperous route and was built of an earlier business community under Shalmaneser I (1274-1245 BCE). Through the centuries, it was in disrepair.[8]

Capital of the Empire

The city was established from a previous settlement during the rule of Shalmaneser I (1274-1245 BCE). Ashurnasirpal II ordered the removal of debris from the towers and walls and wanted the construction of a new city. This new city would have a new royal mansion of superior size, bigger than previous monarchs'.[9]

The kings of Assyria continued to be buried in Assur, but their queens were buried in Kalhu. Kalhu is known today as Nimrud because the archaeologists of the 19th and 20th centuries gave it that name, believing it was the legendary city of the biblical Nimrod, which is mentioned in the Book of Genesis.[10]

A grand opening ceremony with festivities and an opulent banquet in 864 BC is described in an inscribed stele discovered during archeological excavations.[11] By 800 BC Nimrud had grown to 75,000 inhabitants making it the largest city in the world.[12][13]

King Ashurnasirpal's son Shalmaneser III (858–823 BC) continued where his father had left off. At Nimrud he built a palace that far surpassed his father's. It was twice the size and it covered an area of about 5 hectares (12 acres) and included more than 200 rooms.[14] He built the monument known as the Great Ziggurat, and an associated temple.

Nimrud remained the capital of the Assyrian Empire during the reigns of Shamshi-Adad V (822–811 BC), Adad-nirari III (810–782 BC), Queen Semiramis (810–806 BC), Adad-nirari III (806–782 BC), Shalmaneser IV (782–773 BC), Ashur-dan III (772–755 BC), Ashur-nirari V (754–746 BC), Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 BC) and Shalmaneser V (726–723 BC). Tiglath-Pileser III in particular, conducted major building works in the city, as well as introducing Eastern Aramaic as the lingua franca of the empire, whose dialects still endure among the Christian Assyrians of the region today.

However, in 706 BC Sargon II (722–705 BC) moved the capital of the empire to Dur Sharrukin, and after his death, Sennacherib (705–681 BC) moved it to Nineveh. It remained a major city and a royal residence until the city was largely destroyed during the fall of the Assyrian Empire at the hands of an alliance of former subject peoples, including the Babylonians, Chaldeans, Medes, Persians, Scythians, and Cimmerians (between 616 BC and 599 BC).

Later geographical writings

Ruins of a similarly located Assyrian city named "Larissa" were described by Xenophon in his Anabasis in the 5th century BC.[15]

A similar locality was described in the Middle Ages by a number of Arabic geographers including Yaqut al-Hamawi, Abu'l-Fida and Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi, using the name "Athur" (meaning Assyria) near Selamiyah.[note 3]

Remove ads

Archaeology

Summarize

Perspective

Early writings and debate over name

1851 sketch of Layard's expedition removing a Lamassu

1849 sketch of Layard's expedition transporting a Lamassu

Many of Nineveh's archeological remains were transported to the major museums of the 19th century, including the British Museum and the Louvre

Nimrud

The name Nimrud in connection with the site in Western writings was first used in the travelogue of Carsten Niebuhr, who was in Mosul in March 1760. Niebuhr [3] [note 1]

In 1830, traveller James Silk Buckingham wrote of "two heaps called Nimrod-Tuppé and Shah-Tuppé... The Nimrod-Tuppé has a tradition attached to it, of a palace having been built there by Nimrod".[16][17]

However, the name became the cause of significant debate amongst Assyriologists in the mid-nineteenth century, with much of the discussion focusing on the identification of four Biblical cities mentioned in Genesis 10: "From that land he went to Assyria, where he built Nineveh, the city Rehoboth-Ir, Calah and Resen".[18]

Larissa / Resen

The site was described in more detail by the British traveler Claudius James Rich in 1820, shortly before his death.[1] Rich identified the site with the city of Larissa in Xenophon, and noted that the locals "generally believe this to have been Nimrod's own city; and one or two of the better informed with whom I conversed at Mousul said it was Al Athur or Ashur, from which the whole country was denominated."[note 4]

The site of Nimrud was visited by William Francis Ainsworth in 1837.[1] Ainsworth, like Rich, identified the site with Larissa (Λάρισσα) of Xenophon's Anabasis, concluding that Nimrud was the Biblical Resen on the basis of Bochart's identification of Larissa with Resen on etymological grounds.[note 2]

Rehoboth

The site was subsequently visited by James Phillips Fletcher in 1843. Fletcher instead identified the site with Rehoboth on the basis that the city of Birtha described by Ptolemy and Ammianus Marcellinus has the same etymological meaning as Rehoboth in Hebrew.[note 5]

Ashur

Sir Henry Rawlinson mentioned that the Arabic geographers referred to it as Athur. British traveler Claudius James Rich mentions, "one or two of the better informed with whom I conversed at Mosul said it was Al Athur or Ashur, from which the whole country was denominated."[note 4]

Nineveh

Prior to 1850, Layard believed that the site of "Nimroud" was part of the wider region of "Nineveh" (the debate as to which excavation site represented the city of Nineveh had yet to be resolved), which also included the two mounds today identified as Nineveh-proper, and his excavation publications were thus labeled.[note 6]

Calah

Henry Rawlinson identified the city with the Biblical Calah[19] on the basis of a cuneiform reading of "Levekh" which he connected to the city following Ainsworth and Rich's connection of Xenophon's Larissa to the site.[note 2]

Excavations

Initial excavations at Nimrud were conducted by Austen Henry Layard, working from 1845 to 1847 and from 1849 until 1851.[20] Following Layard's departure, the work was handed over to Hormuzd Rassam in 1853-54 and then William Loftus in 1854–55.[21][22]

After George Smith briefly worked the site in 1873 and Rassam returned there from 1877 to 1879, Nimrud was left untouched for almost 60 years.[23]

A British School of Archaeology in Iraq team led by Max Mallowan resumed digging at Nimrud in 1949; these excavations resulted in the discovery of the 244 Nimrud Letters. The work continued until 1963 with David Oates becoming director in 1958 followed by Julian Orchard in 1963.[24][25][26][27][28]

Subsequent work was by the Directorate of Antiquities of the Republic of Iraq (1956, 1959–60, 1969–78 and 1982–92),[29] the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology University of Warsaw directed by Janusz Meuszyński (1974–76),[30] Paolo Fiorina (1987–89) with the Centro Ricerche Archeologiche e Scavi di Torino who concentrated mainly on Fort Shalmaneser, and John Curtis (1989).[29] In 1974 to his untimely death in 1976 Janusz Meuszyński, the director of the Polish project, with the permission of the Iraqi excavation team, had the whole site documented on film—in slide film and black-and-white print film. Every relief that remained in situ, as well as the fallen, broken pieces that were distributed in the rooms across the site were photographed. Meuszyński also arranged with the architect of his project, Richard P. Sobolewski, to survey the site and record it in plan and in elevation.[31] As a result, the entire relief compositions were reconstructed, taking into account the presumed location of the fragments that were scattered around the world.[30]

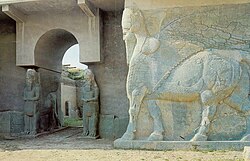

Excavations revealed remarkable bas-reliefs, ivories, and sculptures. A statue of Ashurnasirpal II was found in an excellent state of preservation, as were colossal winged man-headed lions weighing 10 short tons (9.1 t) to 30 short tons (27 t)[32] each guarding the palace entrance. The large number of inscriptions dealing with king Ashurnasirpal II provide more details about him and his reign than are known for any other ruler of this epoch. The palaces of Ashurnasirpal II, Shalmaneser III, and Tiglath-Pileser III have been located. Portions of the site have been also been identified as temples to Ninurta and Enlil, a building assigned to Nabu, the god of writing and the arts, and as extensive fortifications.

In 1988, the Iraqi Department of Antiquities discovered four queens' tombs at the site.

Artworks

Nimrud has been one of the main sources of Assyrian sculpture, including the famous palace reliefs. Layard discovered more than half a dozen pairs of colossal guardian figures guarding palace entrances and doorways. These are lamassu, statues with a male human head, the body of a lion or bull, and wings. They have heads carved in the round, but the body at the side is in relief.[33] They weigh up to 27 tonnes (30 short tons). In 1847 Layard brought two of the colossi weighing 9 tonnes (10 short tons) each including one lion and one bull to London. After 18 months and several near disasters he succeeded in bringing them to the British Museum. This involved loading them onto a wheeled cart. They were lowered with a complex system of pulleys and levers operated by dozens of men. The cart was towed by 300 men. He initially tried to hook up the cart to a team of buffalo and have them haul it. However the buffalo refused to move. Then they were loaded onto a barge which required 600 goatskins and sheepskins to keep it afloat. After arriving in London a ramp was built to haul them up the steps and into the museum on rollers.

Additional 27-tonne (30-short-ton) colossi were transported to Paris from Khorsabad by Paul Emile Botta in 1853. In 1928 Edward Chiera also transported a 36-tonne (40-short-ton) colossus from Khorsabad to Chicago.[32][34] The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has another pair.[35]

The Statue of Ashurnasirpal II, Stela of Shamshi-Adad V and Stela of Ashurnasirpal II are large sculptures with portraits of these monarchs, all secured for the British Museum by Layard and the British archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam. Also in the British Museum is the famous Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, discovered by Layard in 1846. This stands six-and-a-half-feet tall and commemorates with inscriptions and 24 relief panels the king's victorious campaigns of 859–824 BC. It is shaped like a temple tower at the top, ending in three steps.[36]

Series of the distinctive Assyrian shallow reliefs were removed from the palaces and sections are now found in several museums (see gallery below), in particular the British Museum. These show scenes of hunting, warfare, ritual and processions.[37] The Nimrud Ivories are a large group of ivory carvings, probably mostly originally decorating furniture and other objects, that had been brought to Nimrud from several parts of the ancient Near East, and were in a palace storeroom and other locations. These are mainly in the British Museum and the National Museum of Iraq, as well as other museums.[38] Another storeroom held the Nimrud Bowls, about 120 large bronze bowls or plates, also imported.[39]

The "Treasure of Nimrud" unearthed in these excavations is a collection of 613 pieces of gold jewelry and precious stones. It has survived the confusions and looting after the invasion of Iraq in 2003 in a bank vault, where it had been put away for 12 years and was "rediscovered" on June 5, 2003.[40]

Significant inscriptions

One panel of the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III has an inscription which includes the name mIa-ú-a mar mHu-um-ri-i While Rawlinson originally translated this in 1850 as "Yahua, son of Hubiri", a year later Reverend Edward Hincks, suggested that it refers to King Jehu of Israel (2 Kings 9:2 ff. While other interpretations exist, the obelisk is widely viewed by biblical archaeologists as therefore including the earliest known dedication of an Israelite. Note: all the kings of Israel were called "sons of Omri" by the Assyrians ("mar" means "son").

A number of other artifacts considered important to Biblical history were excavated from the site, such as the Nimrud Tablet K.3751 and the Nimrud Slab. The bilingual Assyrian lion weights were important to scholarly deduction of the history of the alphabet.

Remove ads

Destruction

Summarize

Perspective

Nimrud's various monuments had faced threats from exposure to the harsh elements of the Iraqi climate. Lack of proper protective roofing meant that the ancient reliefs at the site were susceptible to erosion from wind-blown sand and strong seasonal rains.[42]

In mid-2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) occupied the area surrounding Nimrud. ISIL destroyed other holy sites, including the Mosque of the Prophet Jonah in Mosul. In early 2015, they announced their intention to destroy many ancient artifacts, which they deemed idolatrous or otherwise un-Islamic; they subsequently destroyed thousands of books and manuscripts in Mosul's libraries.[43] In February 2015, ISIL destroyed Akkadian monuments in the Mosul Museum, and on March 5, 2015, Iraq announced that ISIL militants had bulldozed Nimrud and its archaeological site on the basis that they were blasphemous.[44][45][46]

A member of ISIL filmed the destruction, declaring, "These ruins that are behind me, they are idols and statues that people in the past used to worship instead of Allah. The Prophet Muhammad took down idols with his bare hands when he went into Mecca. We were ordered by our prophet to take down idols and destroy them, and the companions of the prophet did this after this time, when they conquered countries."[47] ISIL declared an intention to destroy the restored city gates in Nineveh.[45] ISIL went on to do demolition work at the later Parthian ruined city of Hatra.[48][49] On April 12 2015, an online militant video purportedly showed ISIL militants hammering, bulldozing, and ultimately using explosives to blow up parts of Nimrud.[50][51]

Irina Bokova, the director general of UNESCO, stated "deliberate destruction of cultural heritage constitutes a war crime".[52] The president of the Syriac League in Lebanon compared the losses at the site to the destruction of culture by the Mongol Empire.[53] In November 2016, aerial photographs showed the systematic leveling of the Ziggurat by heavy machines.[54] On 13 November 2016, the Iraqi Army recaptured the city from ISIL. The Joint Operations Command stated that it had raised the Iraqi flag above its buildings and also captured the Assyrian village of Numaniya, on the edge of the town.[55] By the time Nimrud was retaken, around 90% of the excavated part of the city had been destroyed entirely. Every major structure had been damaged, the Ziggurat of Nimrud had been flattened, only a few scattered broken walls remained of the palace of Ashurnasirpal II, the Lamassu that once guarded its gates had been smashed and scattered across the landscape.

Reconstruction of the site

A renovation program started in July 2017 with the support of UNESCO. The first phase included conducting studies of the damage caused to the site, assembling an Iraqi maintenance and rehabilitation team, preservation and archiving of the city's cultural heritage in co-operation with the American Smithsonian Institution. Phase 2 was launched in October 2019 with the goal to restore the northern palace.[56]

As of 2020, archaeologists from the Nimrud Rescue Project have carried out two seasons of work at the site, training native Iraqi archaeologists on protecting heritage and helping preserve the remains. Plans for reconstruction and tourism are in the works but will likely not be implemented within the next decade.[57] The first major excavation works, launched in mid-October 2022 by an excavation team from the University of Pennsylvania, reported the discovery of a door sill slab with inscriptions in December.[58]

Security post Islamic State

Following the liberation from Islamic State, the security of the ancient city is run by the ethnic Assyrian security force Nineveh Plain Protection Units.[59]

Remove ads

Gallery

- Items excavated from Nimrud, located in museums around the world

- Nimrud ivory plaque, with original gold leaf and paint, depicting a lion killing a human (British Museum)

- Assyrian lion hunt (Pergamon)

- Lamassu, Stelas, Statue, Relief Panels, including the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III (British Museum)

- City under siege (British Museum)

- Cavalry battle (British Museum)

- Eagle-headed deity (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

- Relief with Winged Genius (Walters Art Museum)

- Two Nimrud ivories made in Egypt (British Museum)

- Two archers (Hermitage Museum)

- A human-headed and winged apkallu holding a pine cone and bucket for religious rituals (Museum of the Ancient Orient)

- The first publication of a Phoenician metal bowl, one of 16 metal bowls from Nimrud with a Phoenician inscription (see letters on top sketch of the side profile)

Remove ads

See also

Notes

- Niebuhr wrote on p.355: [in original German]: "Bei Nimrud, einem verfallenen Castell etwa 8 Stunden von Mosul, findet man ein merkwürdigeres Werk. Hier ist von beiden Ufern ein Damm in den Tiger gebaut, um so viel Wasser zurück zu halten, als nöthig ist, die benachbarten Ländereien zu wässern." / [translated]: At Nimrud, a dilapidated castle about 8 hours outside of Mosul, one finds a more remarkable work. Here are both banks of a dam built in the Tigris to hold back as much water as is necessary to water the neighbouring lands."

- William Francis Ainsworth, who preferred the identification of Resen with Nimrud (on the basis of Bochart's identification of Resen with Xenophon's Larissa), summarised the debate in 1855 as follows: "The learned Bochart first advanced the supposition that this Assyrian city was the same as the primeval city, called Resen in the Bible and that the Greeks having asked its name were answered, Al Resen, the article being prefixed, and from whence they made Larissa, in an easy transposition. I adopted this presumed identity as extremely probable, and Colonel Chesney (ii. 223) has done the same, not as an established fact, but as a presumed identity. ... In 1846, Colonel Rawlinson, speaking of Nimrud, noticed it as probably the Rehoboth of Scripture, but he added in a note, 'I have no reason for identifying it with Rehoboth, beyond its evident antiquity, and the attribution of Resen and Calah to other sites.' (Journal of Roy. Asiat. Soc. vol. x. p. 26.) At this time Colonel Rawlinson identified Calah with Holwan or Sir Pul-i-Zohab, and Resen, or Dasen, with Yasin Teppeh in the plain of Sharizur in Kurdistan. In 1849 (Journ. of Roy. Asiat. Soc. vol. xi. p. 10), Colonel Rawlinson said, 'The Arabic geographers always give the title of Athur to the great ruined capital near the mouth of the Upper Zab. The ruins are now usually known by the name of Nimrud. It would seem highly probable that they represent the Calah of Genesis, for the Samaritan Pentateuch names this city Lachisa, which is evidently the same title as the Λάρισσα of Xenophon, the Persian r being very usually replaced both in Median and Babylonian by a guttural.' In 1850 (Journ. of Roy. Asiat. Soc. vol. xii.). Colonel Rawlinson added the discovery of a cuneiform inscription bearing the title Levekh, which he reads Halukh. 'Nimrud', says the distinguished palaeographist, 'the great treasure-house which has furnished us with all the most remarkable specimens of Assyrian sculpture, although very probably forming one of that group of cities, which in the time of the prophet Jonas, were known by the common name of Nineveh, has no claim, itself, I think, to that particular appellation. The title by which it is designated on the bricks and slabs that form its buildings, I read doubtfully as Levekh, and I suspect this to be the original form of the name which appears as Calah in Genesis, and Halah in Kings and Chronicles, and which indeed, as the capital of Calachene, must needs have occupied some site in the Immediate vicinity.' Lastly, in 1853 (Journ. of Roy. Asiat. Soc. vol. xv. p. vi. et seq.), Colonel Rawlinson describes the remarkable cylinder before alluded to as found at Kilah Shirgat, which establishes that site to have been the most ancient capital of the Assyrian empire, and to have been called Assur as well as Nimrud and Nineveh Proper. This Assur, we have seen, he identifies with the Tel Assur of the Targums, which is used for the Mosaic Resen; and instead, therefore, of Resen being between Nineveh and Calah, It should be Calah, which was between Nineveh and Resen. But, notwithstanding such very high authority, the conclusion thus arrived at does not appear to be perfectly satisfactory."

- Layard (1849, p.194) noted the following in a footnote: "Yakut, in his geographical work called the Moejem el Buldan, says, under the head of "Athur," "Mosul, before it received its present name, was called Athur, or sometimes Akur, with a kaf. It is said that this was anciently the name of el Jezireh (Mesopotamia), the province being so called from a city, of which the ruins are now to be seen near the gate of Selamiyah, a small town, about eight farsakhs east of Mosul; God, however, knows the truth." The same notice of the ruined city of Athur, or Akur, occurs under the head of "Selamiyah." Abulfeda says, " To the south of Mosul, the lesser (?) Zab flows into the Tigris, near the ruined city of Athur." In Reinaud's edition (vol. i. p. 289, note 11,) there is the following extract from Ibn Said: — " The city of Athur, which is in ruins, is mentioned in the Taurat (Old Testament). There dwelt the Assyrian kings who destroyed Jerusalem.""

- Rich (1836, p.129) described his interpretation as follows: "I was curious to inspect the ruins of Nimrod, which I take to be the Larissa of Xenophon. They were sufficiently visible from the shore to enable me to sketch the principal mount. About a quarter of a mile [400 m] from the west face of the platform is the large village of Nimrod, sometimes called Deraweish. The Turks generally believe this to have been Nimrod's own city; and one or two of the better informed with whom I conversed at Mousul said it was Al Athur or Ashur, from which the whole country was denominated. It is curious that the villagers of Deraweish still consider Nimrod as their founder. The village story-tellers have a book they call the "Kisseh Nimrod," or Tales of Nimrod, with which they entertain the peasants on a winter night. [Footnote: In the name of this obscure place seems to be preserved that of the first settler of the country, and from this spot, perhaps, that name extended over the whole vast region. See Gen. x. 11 . "Out of that land went forth Ashur and builded Nineveh," &c.; or, as it has been rendered, "Out of that land he went forth into Ashur,"i.e. Assyria. The former translation seems the preferable one; and the position of this village is avourable to the supposition of its having received very early a name afterwards to become so celebrated.]"

- Fletcher (1850, p.75-78) described his thesis as follows: "The Tell of Nimroud and its lately discovered treasures have excited so much interest that I trust I may be pardoned if I interrupt the course of the narrative to bestow a few remarks on the identity of this site with that of the ancient city of Rehoboth, mentioned in Genesis x. 11. It is evident from the sculptures which have been discovered at Nimroud, that these mounds were in ancient days occupied by some large Assyrian city. Major Rawlinson, in his interesting paper on Assyrian Antiquities, quoted in the Athenceum of January 26, 1850, assumes that the ruins of Nimroud represent the old city of Calah, or Halah, while he places Nineveh at Nebbi Yunas. Yet it appears likely that the ancient Calah, or Halah, which was probably the capital of the district of Calachene, must have been nearer to the Kurdish Mountains. Ptolemy mentions the province of Calachene as bounded on the north by the Mountains of Armenia, and on the south by the district of Adiabene. [Ptolemy, lib. vi. cap. i.] Most writers place Ninus, or Nineveh, within the latter province. But if so, Adiabene would include also Nimroud, and, therefore, it is not probable that Halah, or Calah, could have occupied the site indicated by Major Rawlinson. St. Ephraim, himself a learned Syrian and well acquainted with the history and geography of the East, considers Calah to be the modern Hatareh, a large town inhabited chiefly by Yezidees, and situated N.N.W. of Nineveh. [Strabo, lib. 1G, mentions the plain in the vicinity of Nineveh, and seems to consider it as not belonging to the province of Adiabene. But his testimony, if taken, would also exclude that city, and the land to the southward of it, from the district of Calachene, as he enumerates that as a distinct part of Assyria immediately afterwards. In the arrangement of the dioceses recorded in Assemani, torn. iii. Athoor and Adiabene seem to be continually connected, while Calachene is spoken of as nearer the mountains.] Between Hatareh and the site of Nineveh we find a village bearing the name of Ras el Ain, which is evidently a corrupted form of the Resen of Genesis. It is worthy of remark that this theory confirms the statement made in Genesis x. 12, where Resen is represented as occupying a midway position between Calah and Nineveh. But assuming Major Rawlinson's hypothesis to be correct, it is clear that there would be no room for a large city between Nebbi Yunas and Nimroud, a distance of, at most, 40 kilometres (25 mi). Nor is it certain that the latter may be considered as the site of the Larissa of Xenophon. A considerable interval must have taken place between the passage of the river Zab by the Ten Thousand and their arrival at the Tigris. It is expressly mentioned that they forded a mountain stream, which seems to have been of some width, soon after they had passed over the Zab. But no vestige of any stream of this kind appears between Nimroud and the Tigris. It is probable, therefore, that the Χαραδρα of Xenophon was the Hazir, or Bumadas, after passing which, the Ten Thousand marched in a north-westerly direction past the modern village of Kermalis to the Tigris. At a short distance from the latter they encountered a ruined city, which Xenophon terms Larissa, and which occupied probably the site of the modern Ras el Ain. The village known by this name is about 19 kilometres (12 mi) from the Tigris, but the ancient city may have been much nearer. [Xenophon Anab. lib. iii. cap. iv.] Both Ptolemy and Ammianus Marcellinus mention a city situated at the mouth of the Zab, on precisely the same site as that occupied by the mounds of Nimroud, which they term Birtha, or Virtha. But Birtha, or Britha, in Chaldee, signifies the same as Rehoboth in Hebrew, namely, wide squares or streets, an identity in name which seems to imply also an identity in locality. It appears likely, therefore, that Nimroud is the same as Rehoboth, which it is said Asshur founded after his departure from the land of Shinar."

- Layard, Nineveh and its Remains, "That the ruins at Nimroud were within the precincts of Nineveh, if they do not alone mark its site, appears to be proved by Strabo, and by Ptolemy's statement that the city was on the Lycus, corroborated by the tradition preserved by the earliest Arab geographers. Yakut, and others mention the ruins of Athur, near Selamiyah, which gave the name of Assyria to the province; and Ibn Said expressly states, that they were those of the city of the Assyrian kings who destroyed Jerusalem. They are still called, as it has been shown, both Athur and Nimroud. The evidence afforded by the examination of all the known ruins of Assyria, further identifies Nimroud with Nineveh. It would appear from existing monuments, that the city was originally founded on the site now occupied by these mounds. From its immediate vicinity to the place of junction of two large rivers, the Tigris and the Zab, no better position could have been chosen."

Remove ads

Citations

General references

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads