The 1939 New York World's Fair (also known as the 1939–1940 New York World's Fair) was an international exposition at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in Queens, New York City, United States. The fair included exhibitions, activities, performances, films, art, and food presented by 62 nations, 35 U.S. states and territories, and 1,400 organizations and companies. Slightly more than 45 million people attended over two seasons. It was based on "the world of tomorrow", with an opening slogan of "Dawn of a New Day". The 1,202-acre (486 ha) fairground consisted of seven color-coded zones, as well as two standalone focal exhibits. The fairground had about 375 buildings.

| 1939 New York City | |

|---|---|

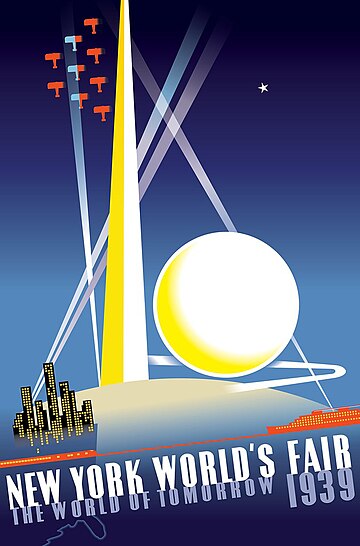

Poster by Joseph Binder | |

| Overview | |

| BIE-class | Universal exposition |

| Category | Second category General Exposition |

| Name | New York World's Fair |

| Motto | The World of Tomorrow |

| Area | 1,202 acres (486 hectares) |

| Organized by | Grover Whalen |

| Participant(s) | |

| Countries | 62 |

| Organizations | 1,400 |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| City | New York City |

| Venue | Flushing Meadows–Corona Park |

| Coordinates | 40°44′39″N 73°50′40″W |

| Timeline | |

| Opening | April 30, 1939 (first season) May 11, 1940 (second season) |

| Closure | October 31, 1939 (first season) October 27, 1940 (second season) |

| Universal expositions | |

| Previous | Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne in Paris |

| Next | Exposition internationale du bicentenaire de Port-au-Prince in Port-au-Prince |

| Specialized Expositions | |

| Previous | Second International Aeronautic Exhibition (1938) in Helsinki |

| Next | International Exhibition on Urbanism and Housing (1947) in Paris |

| Simultaneous | |

| Universal | Golden Gate International Exposition |

| Specialized | Exposition internationale de l'eau in Liège |

Plans for the 1939 World's Fair were first announced in September 1935, and the New York World's Fair Corporation (WFC) began constructing the fairground in June 1936. The fair opened on April 30, 1939, coinciding with the 150th anniversary of the first inauguration of George Washington. When World War II began four months into the 1939 World's Fair, many exhibits were affected, and some exhibits were forced to close after the first season. The fair attracted over 45 million visitors and ultimately recouped only 32% of its original cost. After the fair ended on October 27, 1940, most pavilions were demolished or removed, though some buildings were relocated or retained for the 1964 New York World's Fair on the same site.

The fair hosted many activities and cultural events. Participating governments, businesses, and organizations were celebrated on specific theme days. Musical performances took place in conjunction with the fair, and sculptures and artworks were displayed throughout the fairground and within pavilions. The fairground also displayed consumer products, including electronic devices, and there were dozens of restaurants and concession stands. The exposition spurred increased spending in New York City and indirectly influenced Queens's further development. Artifacts from the fair still exist, and the event has also been dramatized in media.

Development

New York City had hosted the United States' first world's fair, the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, in 1853–1854;[1] the city did not host another world's fair for 85 years.[2] The site of the 1939 World's Fair, Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in Queens, was originally a natural wetland straddling the Flushing River[3] before becoming an ash dump in the early 20th century.[4] New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses first conceived the idea of developing a large park in Flushing Meadows in the 1920s.[5] Although the neighborhoods around Flushing Meadows contained residential developments, the meadow itself remained undeveloped and isolated.[6] Meanwhile, the 1933 Century of Progress exposition in Chicago had boosted that city's economy, prompting businesspeople in New York City to consider a similar fair.[7][8]

Planning

Early plans

The New York Times attributes the idea for the 1939 New York World's Fair to the civil engineer Joseph Shadgen, who had come up with the idea in 1934 following a conversation with his daughter.[9] By early 1935, a group led by the municipal reformer George McAneny was considering an international exposition in New York City in 1939.[7][10] Though the date coincided with the 150th anniversary of George Washington's first inauguration,[10][11] Moses said the date was "an excuse and not the reason" for the fair.[11] That September, the group announced plans to spend $40 million to host an exhibition at the 1,003-acre (406 ha) Flushing Meadows site.[12] The New York City Board of Estimate approved the use of Flushing Meadows as a fairground on September 23,[13] and Moses directed municipal draftsmen to survey the site.[14] The Flushing Meadows site had been selected because of its large size and central location,[15] and the city already owned 586 acres (237 ha) nearby.[16]

Mayor Fiorello La Guardia pledged financial support for the fair that October;[17] at the time, Moses estimated that it would cost $5–7 million to prepare the fairground and build transit to the fair.[18] The New York World's Fair Corporation (WFC) was formed to oversee the exposition on October 22, 1935,[19] and the Board of Estimate allocated $200,000 the next day for preliminary work.[20] The WFC elected McAneny as its president,[7][21] and two contractors were hired that December to conduct preliminary surveys.[22] Several foreign exhibitors had expressed interest in the fair before the end of the year,[23] and the WFC and the New York City Board of Transportation devised plans for public transit lines to the fair.[24]

Lease and financing

State lawmaker Herbert Brownell Jr. proposed legislation in January 1936, allowing the city government to formally lease the Flushing Meadows site to the WFC.[25] Moses warned that the fairground's completion could be delayed due to funding issues; by then, the fair was estimated to cost $45 million.[26][27] That February, McAneny announced that he would organize a committee to devise an architectural plan for the fairground.[28] The committee initially advocated for a single massive building.[7] Brownell requested funding from New York governor Herbert Lehman the same month for "basic World's Fair improvements";[29] the city and state governments were each supposed to spend $5 million on site preparations.[30] The project remained stalled during early 1936 because of disagreements over the fair's location and financing.[30][31] There was a competing proposal to relocate the fair to Marine Park in Brooklyn.[31][32] but the New York State Legislature ultimately voted in April to allow the city to lease out Flushing Meadows.[33]

In April 1936, Grover Whalen replaced McAneny as the WFC's chairman;[7][34] he was later elected as the agency's full-time president as well.[35] J. Franklin Bell was hired to draw up preliminary plans for the fair,[36] and the WFC appointed a committee of seven men[lower-alpha 1] to devise a plan for the fairground.[38][37] At the end of the month, the city government announced plans to sell $7 million in bonds, and the state pledged $4.125 million for the project.[39] In addition, the WFC was to sell $20 million in bonds;[16] the WFC eventually ended up issuing $26,862,800 worth of bonds.[40] The New York City Board of Estimate appropriated $308,020 to begin landscaping the site that May,[41] and city officials acquired another 372 acres (151 ha) through eminent domain.[42] The WFC dedicated the fairground site on June 4, 1936,[43] shortly before the city finalized its lease of Flushing Meadows to the WFC in June 1936.[44]

Construction

Work on the World's Fair site began on June 16, 1936,[45] and a groundbreaking ceremony for the fairground took place on June 29.[46] The WFC established seven departments and thirteen committees to coordinate the fair's development.[16] The fair was planned to employ 35,000 people.[47] The construction of the fairground involved leveling the ash mounds; excavating Meadow and Willow lakes; and diverting much of the Flushing River into underground culverts.[48][49][50] The dirt from the lake sites was used as additional topsoil for the park.[51] Workers also transported soil from Westchester County, New York, to the fairground.[52] Four hundred fifty workers were employed on three eight-hour shifts.[53] The rebuilt landscape was to be retained after the fair.[54][55] The city, state, and federal governments also worked on 48 infrastructure-improvement projects, such as highway and landscaping projects, for the fair.[56]

To promote the fair, the WFC established advisory committees with members from every U.S. state.[57] Several baseball teams wore patches promoting the fair during the 1938 Major League Baseball season,[58] while the businessman Howard Hughes named an airplane after the fair and flew it around the world in 1938.[59][60] Helen Huntington Hull led a women's committee that helped promote and develop the fair.[61] New York license plates from 1938 were supposed to have slogans advertising the fair,[62] but a city judge deemed the slogans unconstitutional.[63] New York license plates from 1939 and 1940 also advertised the fair.[64] Local retailers also sold more than $40 million worth of merchandise with World's Fair motifs,[65] and the U.S. government issued stamps depicting the fair's Trylon and Perisphere.[66] World leaders delivered "greetings to the fair" as part of the "Salute of the Nations" radio program,[67] and the WFC also broadcast 15-minute-long "invitations to the fair", featuring musical entertainments and a speech by Gibson.[68] In addition, the WFC distributed a promotional film, Let's Go to the Fair.[69]

1936 and 1937

The WFC's board of design reviewed several proposed master plans for the site,[70] and the corporation had relocated the last occupants of the fairground site by August 1936.[71] The WFC launched a design competition for several fairground pavilions that September[72] and selected several winning designs two months later.[73] Before the final master plan was revealed, Whalen said the fair would likely be dedicated to the past, present, and future.[74] The WFC announced details of the fair's master plan that October, which called for a $125 million exposition themed to "the world of tomorrow".[75][76] The city, state, and federal governments would spend $35 million; the WFC was to spend $30 million; and the remaining funds would come from individual exhibitors.[77] There were to be ten zones, an amusement area, a central tower with paths radiating away from it, and extensive public-transit improvements.[76] Later that month, the WFC signed construction contracts for the fairground's first building.[78] At that point, only a small number of fairground buildings had been approved.[47]

In November 1936, France became the first nation to announce its participation,[79] and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt urged other nations to join the fair.[80] The city government also began selling bonds for the fair that month,[81] and several nations and hundreds of businesses had expressed interest.[82] That December, the International Convention Bureau endorsed the 1939 World's Fair, allowing the bureau's 21 member countries to host exhibits there,[83] and Lehman also invited the governors of all other U.S. states.[84] By the beginning of 1937, eleven hundred concessionaires had applied for concessions at the fair,[85] and nine buildings were under construction.[86] The WFC unveiled a model of the fairground at its Empire State Building headquarters that March.[87] Workers had finished grading and filling the World's Fair site by April,[88] and they began planting trees on the fairground.[89] That month, AT&T became the first company to lease a pavilion at the fair,[90][91] and work officially began on the first building, the administration structure.[92] In addition, the WFC began auctioning off the fairground's concession spaces,[93] and workers also began planting trees in early 1937.[94] Whalen predicted that the fair would attract 59 nations.[95] Shadgen, who had devised the idea for the fair, was ousted from the WFC that year.[96]

Whalen announced plans in June 1937 for a 280-acre (110 ha) amusement zone at the south end of the fairground,[97] and Moses proposed adding a trailer parking lot and a community interests zone.[98] Work on the first non-commercial pavilion, the Temple of Peace, began in July.[99] The fairground's first structure, the administration building, was completed by the next month.[100] At the time, 89 buildings were under construction,[101] and 86% of the fairground sites had been leased.[101][102] Utah became the first U.S. state to lease space in the fair's Hall of States that September,[103] while Missouri was the first state to lease space for a standalone building.[104] Whalen also traveled to Europe to invite European countries to the fair.[105] The WFC reported in October that 62 construction contracts had been finished and that another 63 were in progress.[106] Various fairground buildings were rapidly being developed, as well as the Trylon and Perisphere, the fair's icons.[107][108] That December, the Ford Motor Company became the first automobile manufacturer to lease space at the fair;[109] by then, the WFC had received commitments from 60 nations.[110]

1938 and 1939

The WFC awarded the first fair concession in January 1938;[111] by then, Whalen was making plans for the fair's opening ceremony.[112] Whalen wanted to have 100 buildings under construction by the end of April,[113] and the WFC planned to spend $10 million on upgrading the fairground's utilities.[114] Work on the Perisphere, the fair's theme building, began in early April,[115] along with work on the first foreign-government structure.[116] The same month, the WFC leased out the last vacant sites in the fair's Government Zone.[117] Exactly one year before the fair's expected opening, the city hosted a parade with 1 million spectators on April 30, 1938;[118] the WFC also hosted a fireworks show the next week.[119] That May, the WFC began allowing visitors to inspect the fairground on weekends for a fee.[120] By then, many of the buildings were under construction.[121] The structures were all supposed to be completed by the end of March 1939, giving one month for exhibitors to fit their pavilions out.[122]

The WFC awarded contracts to 30 amusement-ride operators in June 1938, following months of disputes over the concessions.[123] Work was delayed for three weeks in July during a labor strike.[124] and the delivery of materials was delayed that September during the New York City truckers' strike.[125] The WFC continued to issue concessions for eateries and amusement rides.[126] By late 1938, workers were painting murals on buildings, and the subway stations serving the fairground were being completed.[127] That October, the Heinz Dome became the first commercial exhibit to be completed,[128] and 80% of the fairground's 3 million square feet (280,000 m2) of exhibit space had been leased.[129][122] Leasing lagged in the amusement zone; by that December, only two-thirds of the ride concessions had been leased.[130]

Whalen announced in January 1939 that the fairground was more than 90% complete,[56][131] but although 95% of the buildings were under construction, work on one-third of the amusement concessions had not started.[131] The fair had attracted 1,300 industrial exhibitors and 70 concessionaires.[56] In addition, 62 nations and 35 U.S. states or territories had leased space at the fair;[56] their flags were flown atop a hill on the fairground.[132] In March 1939, a month and a half before the fair's official opening, Whalen announced plans to spend $1 million on shows and miniature villages in the Amusement Area.[133] The lights on the fairground were first turned on that April, three weeks before the fair's scheduled opening.[134] In addition, La Guardia issued a proclamation declaring April 1939 as "Dress Up and Paint Up Month" in New York City.[135] Sixteen thousand workers were putting final touches on the site by mid-April,[136] and foreign nations were delivering $100 million worth of exhibits to the fair.[137] Thousands of additional workers were employed toward the end of April.[138]

Operation

The fairground ultimately cost $156,000,000 (equivalent to $3,417,000,000 in 2023), and Whalen anticipated that 60 million people would visit.[139] Five major newsreel companies were hired to provide newsreel coverage,[140] and the Crosley Corporation and WNYC both had radio broadcasting studios there.[141] The WFC hired Exposition Publications to print a guidebook, souvenir book, and daily programs,[142] and it promoted 17 other publications about the fair.[143] The Bureau International des Expositions (BIE) retroactively recognized the 1939 World's Fair as an official World Expo, even though the BIE's rules permitted official Expos to run for only one year.[144]

Whalen agreed to hire only union laborers to install exhibits on the fairground; in exchange, several trade unions agreed to buy the WFC's bonds.[145] Free emergency services were provided on site by dozens of doctors and nurses,[146] and there were six first-aid stations, a mobile X-ray machine, and five ambulances.[147] The fairground was covered by a temporary New York City Police Department (NYPD) precinct[148] and a temporary New York City Fire Department (FDNY) battalion with 118 firefighters.[149] In addition, the Queens County Court was temporarily expanded to hear additional criminal cases relating to the fair.[150]

1939 season

Preparations and opening

For the 1939 season, the WFC charged 75 cents per adult and 25 cents per child; the agency also sold season tickets, multi-visit tickets, and souvenir ticket books.[152] Manhattan borough president Stanley M. Isaacs had wanted the WFC to give students free admission, but Moses opposed the proposal.[153] Whalen began selling discounted advance tickets in February 1939;[154] the corporation wanted to sell at least $3 million in advance tickets.[155] A thousand retailers in the New York metropolitan area sold advance tickets.[156] The fair initially did not distribute free tickets to anyone, although journalists could visit the fairground free of charge.[154] Advance ticket sales were supposed to have ended on April 23, 1939, but the WFC had to print additional souvenir books due to high demand.[157] Though there was an upcharge fee for some of the exhibits and attractions, three-fourths of the original attractions did not charge any extra fees.[158]

On April 30, 1939, exactly 150 years after Washington's first inauguration,[159] the fair formally opened with a speech by President Roosevelt.[160][161] Twenty-eight United States Navy men-of-war arrived in New York City for the fair's opening,[162] and 20,000 people participated in a parade celebrating the opening.[161][163] The fair received 600,000 visitors on its first day, far short of the 1 million visitors that the WFC had predicted.[160][161] At the time, many major attractions in the Amusement Area were incomplete,[164][165] and only 80% of the structures were ready.[166] The fair accommodated one million visitors in its first four days.[167] By mid-May, the fair was 90% finished, but many of the amusement attractions were still incomplete.[168] The WFC's operations department oversaw the remainder of the construction.[169]

May to October

In early May, the WFC began selling 10-cent children's tickets once a week,[170] which helped increase children's attendance significantly.[171][172] At La Guardia's behest,[173] the New York City Board of Education operated guided tours in which school classes could visit the fair for free.[174] Concessionaires in the Amusement Area asked the WFC to consider offering reduced-price tickets after 9 p.m.,[175] and the WFC opened more restaurants late that May.[176] Within a month of the fair's opening, several exhibitors had alleged that labor unions had charged exorbitant prices for labor at the fair,[145][177] and the government of Nevada canceled their exhibit due to high labor-union costs.[178] Due to concerns over sexually explicit content, several of the fair's shows were raided as well.[179] That June, to accommodate high demand, the WFC rescheduled the fair's nightly fountain performances at the Lagoon of Nations,[180] which attracted up to 60,000 observers a night.[171] The same month, the WFC established a committee to oversee the amusement area,[181] and amusement concessionaires agreed to offer discounted ride tickets once a week.[182] The WFC also sold discounted 50-cent tickets to organizations and businesses who bought at least 500 tickets.[183][184]

Lower-than-expected attendance prompted Whalen to fire hundreds of employees in July 1939,[185][186] and there were also proposals to reduce performers' salaries.[187] The same month, the WFC began selling discounted "combination tickets" with snacks and admission to multiple attractions,[188] as well as "bargain books" with food vouchers and admission tickets.[189] At the request of amusement-ride operators,[190] the WFC also considered reducing admission prices.[191] At the beginning of August, admission was reduced to 50 cents during weekends,[192][193] and the WFC started selling discounted 40-cent tickets at night.[193][184] The WFC also began allowing railroads to sell 50-cent tickets to groups of 500 or more passengers.[183][184] With daily attendance averaging 129,000—less than half the original estimate of 270,000—the WFC was unsure if the fair would run for another season.[194] The fair's financial standing was so bad that, by mid-August the WFC was asking bondholders to lend it more money,[195] and the bondholders agreed to forgo their right to collect a portion of the fair's admission revenue.[196] A writer for Variety magazine said local residents tended to avoid the fair's restaurants and that the amusement area deterred visitors with more refined tastes.[197]

In September 1939, the WFC began inviting foreign exhibitors to return for a second season.[198] At the time, Harvey D. Gibson, who led the WFC's board of directors, did not anticipate that the WFC would encounter any financial issues between the two seasons.[199] The same month, the Carrier Corporation was the first industrial exhibitor to renew its lease.[200][201] Southern Rhodesia was the first exhibitor to shutter its pavilion entirely,[202] and other exhibitors curtailed their operations.[202][203] Whalen also traveled to Europe, asking exhibitors to return in 1940.[204][205] At the end of September, the WFC notified the city government that it intended to lease the land for a second season,[206] and the WFC reduced admission fees to 50 cents for the rest of the season.[207] In the final weeks of the 1939 season, visitors increasingly came from outside the New York City area.[205] The final week was celebrated with a Mardi Gras–themed festival.[208]

When the first season ended on October 31, 1939,[209] the WFC had recorded 25,817,265 paying guests.[210][211] Attendance had exceeded 100,000 on 114 days, or about 62% of the season.[212] At the peak of the first season, the WFC had directly employed about 8,500 people, and exhibitors had employed another 16,500.[213] Including workers on temporary permits, the fair had recorded 32.79 million visitors.[214] At the end of the first season, the WFC owed bondholders $23.5 million, and it had $1.13 million on hand.[215] In addition, the fair had handled 8.52 million phone calls and 3.3 million pieces of mail.[214] Around 150 fairgoers had been arrested during the first season,[lower-alpha 2] only one of whom was charged with a felony.[218][219]

Off-season

After the 1939 season ended, many exhibits were removed for safekeeping, and the fairground's utilities were turned off.[213][220] Most of the fair's 2,800 employees were reassigned to other positions,[218] though the WFC hired a skeleton crew and allocated $3.3 million to maintain the fairground during the off-season.[213][220] The FDNY and NYPD watched over the fairground, and many exhibitors also hired their own security guards.[213][221] Because of lower-than-expected attendance,[222] the WFC agreed to reduce adult admission prices to 50 cents.[203][223] The WFC agreed to redesign the Amusement Area to emphasize the rides there.[224] The corporation also tried to attract visitors within an overnight drive from New York City, rather than guests from further afield.[225]

At the requests of several U.S. state exhibitors,[226] the WFC halved rent rates for U.S. state pavilions during the second season.[227] Despite the uncertainty caused by the ongoing war, many European countries expressed interest in returning.[228] In January 1940, Finland became the first country to agree to reopen its pavilion,[229] while West Virginia was the first U.S. state to lease additional space.[230] More than thirty nations had agreed to return to the fair by the end of the next month.[231][232] Several exhibits were also added, including a China pavilion[233] and a European center.[234] Conversely, 11 nations—several of which had been invaded during World War II—did not return,[235] and nine U.S. states also withdrew.[236] Most commercial exhibitors agreed to reopen their exhibits, and some planned to enlarge or modify their exhibits.[220][237] Almost all major exhibitors with their own pavilions renewed their leases for the 1940 season, while most of the exhibitors who had withdrawn were more likely to be renting space from the WFC.[238] The commission also signed agreements with several trade unions to avert strikes and disputes;[239] there was a brief strike in April 1940, while the fairground was preparing to reopen.[240]

The fair was rebranded as the World's Fair 1940 in New York for its second season.[241][242] The WFC decided to focus more heavily on amusement attractions,[243] and it added theaters and free shows.[244][245] The Amusement Area was reduced in size[246] and rebranded as the "Great White Way", a reference to Broadway theatre.[241][247] The transportation zone was renovated for more than $2 million.[248] Several exhibits were added or expanded,[247][249] and some pavilions were repaired due to deterioration.[250] Twenty thousand hotel rooms were added in New York City prior to the 1940 season,[245] and La Guardia promoted low-cost hotel rooms to fairgoers.[251] Low-cost eateries were also added.[245][252] The fair's construction superintendent estimated that the upgrades would cost $8 million.[253] The WFC began selling one million souvenir ticket books on April 11, 1940,[254] and the next week, it began selling discounted tickets to students across the U.S.[255] By the end of April, all of the attractions in the Amusement Area had been leased,[256] and half a million advance tickets had been sold or ordered.[257]

1940 season

Originally, the second season was supposed to open on May 25, 1940, and be one month shorter than the first season.[258] WFC officials claimed that the late opening date would coincide with warmer weather and the end of the school year. Following requests from organizations, the WFC agreed to open the fair two weeks earlier.[259] The fair's police force was downsized for the 1940 season due to low crime rates,[260] and the overall number of staff was reduced to 5,500.[261] According to Gibson, at least 40 million visitors needed to attend during 1940 for the WFC to break even.[262][263] In contrast to the more formal atmosphere that had characterized the first season, the second season had a more informal, "folksy" atmosphere.[263][264] Additionally, the international area included exhibits from 43 countries, plus the Pan-American Union and League of Nations.[235] Adults paid 50 cents, while children paid 25 cents;[245][265] children's admission was reduced to 10 cents on "Children's Days".[245] To entice people to attend the fair, several local business groups and hotels randomly gave 170 automobiles to visitors.[266]

The World's Fair reopened on May 11[267] and recorded 191,196 visitors on that day.[268] The reopening ceremonies were broadcast on radio stations across the U.S.,[269] and La Guardia sponsored a citywide celebration for the fair's reopening.[270] In the first few weeks of the 1940 season, the WFC sold off most of its outstanding debt from the previous season.[271] By the end of June, the WFC wished to reorganize itself and pare its workforce due to lower-than-expected revenue;[272] as such, 500 employees were dismissed.[273] In addition, due to an increase in federal tax rates, amusement concessionaires increased the ticket prices for their rides.[274] The fair's restaurateurs generally absorbed the losses from the higher taxes instead of raising food prices.[275] On July 4, 1940, two NYPD officers investigating a time bomb at the British Pavilion died when the bomb detonated;[276] the bombing was never solved,[277] and visitors were largely unaware that it had even occurred.[278] Following the bombing, security outside European countries' pavilions was increased.[279] Later the same month, the WFC began surveying the fair's buildings, with plans to demolish them.[280]

At the midpoint of the season, in August 1940, the WFC had to postpone paying a dividend to its bondholders.[281] In large part due to inclement weather, some concessionaires considered closing their attractions,[282] and the fair had recorded nearly 3 million fewer visitors during the 1940 season compared with the equivalent time period in 1939.[283] The WFC planned to distribute posters advertising the fair,[283][284] and bondholders agreed to waive $14.5 million of the WFC's debt.[285] The WFC also began selling off materials and memorabilia from the fair.[286] Daily attendance increased gradually, and the fair recorded the ten-millionth visitor of the season at the end of August.[287] By then, Gibson said the fair had made over $2.5 million in profit, despite Moses's claim that the fair was about to go bankrupt.[288] The WFC had drawn up detailed plans for clearing the site by the beginning of October,[289] and the corporation's executive leadership agreed to oversee the site-clearing process.[290]

To promote the fair, hundreds of American newspapers printed discounted tickets that could be redeemed on October 6;[291] the promotion attracted nearly 350,000 visitors on that day.[292] The city government also provided free tickets to adults who were receiving welfare payments through the Home Relief program.[293] By the middle of that month, the fair's second season had recorded a $4.15 million net profit.[294] In the fair's last week, the WFC hosted extravagant shows such as fireworks displays.[295] The fair had 537,952 visitors on its final day, October 27, 1940.[296] The day afterward, passersby were allowed to tour the grounds for $2.[297] In total, the fair had recorded 19,115,713 million visitors during 1940; even accounting for the second season's shorter duration, it had fewer daily visitors on average than in 1939.[210][212] During the 1940 season, attendance had exceeded 100,000 on only 59 days.[212] The fair had attracted just over 45 million visitors across both seasons.[296][298] The 1940 season also recorded little crime, with 96 arrests and one violent crime (the July 4 bombing).[217]

- 1939 World's Fair ephemera

- This 1940 general admission ticket also included visits to "5 concessions" (listed on backside)

- Ticket backside

- Trylon and Perisphere on 1939 US stamp

Fairground

The fairground was divided into seven geographic or thematic zones, five of which had "focal exhibits", and there were two focal exhibits housed in their own buildings.[299][161] The plan called for wide tree-lined pathways converging on the Trylon and Perisphere, the fair's symbol and primary theme center.[51][300] The Trylon and Perisphere were the only structures on the fairground that were painted completely white;[301] the buildings in the surrounding zones were color-coded.[121][302] The fairground had 34 miles (55 km) of sidewalks and 17 miles (27 km) of roads, in addition to dozens of miles of sewers, water mains, gas mains, and electrical ducts.[301] About 850 phone booths were scattered across the fairground.[303] There were 11 entrances to the grounds during the 1939 season[139][161] and 13 entrances during the 1940 season.[265]

Landscape features

From the start, Moses wanted to convert the site into a park after the fair,[304] and the fairground's landscape architect, Gilmore David Clarke, had designed the fairground with this expectation in mind.[300] The central portion of the old Flushing ash dumps became the main fairground, while the southern section of the dumps became the narrow Amusement Area, located on the shore of Meadow (Fountain) Lake.[300] The fairground used up to 400,000 cubic yards (310,000 m3) of topsoil from the New York City area, as well as salty, acidic soil dredged from the bottom of Flushing Meadows Park's lagoons.[94] The fairground included 250 acres (100 ha) of lawns and a wide range of topiary and deciduous trees.[305] Around 10,000 trees were transplanted to the fairground,[94][306] of which more than 97 percent survived the 1939 season.[307] There were no evergreen trees because it was not open during the winter, and the site also did not have rare plants.[308]

The fairground contained 1 million plants, 1 million bulbs, 250,000 shrubs, and 10,000 trees.[161] The site had 7,000 American camassias, 48,000 scillas, and 50,000 narcissi, and there were several formal gardens as well, with roses, yew, and other plants.[309] In addition, the Netherlands donated a million tulip bulbs to the fair,[310][311] though the tulips were destroyed and replaced with other plantings the month after the 1939 season opened.[312] The Washington Post estimated that the WFC spent some $150,000 (equivalent to $3,286,000 in 2023) on plants at the fair.[311] There were also around 50 landscaped gardens.[313] Some of these fountains included water features such as fountains, pools, and brooks.[314] For the 1940 season, annuals and trees were added instead of the tulips,[315] and a woodland garden was added.[316]

Despite the fair's futuristic theme, the fairground's layout—with streets radiating from the theme center—was heavily inspired by classical architecture.[300] Some streets in the fairground were named after notable Manhattan thoroughfares or American historical figures, while others were named based on their function.[317] A central esplanade called Constitution Mall was planned as part of the fairground,[318] running between the Grand Central Parkway to the west and Lawrence Street in Flushing to the east.[319] A curving road named Rainbow Avenue connected the color-coded zones, linking the paths that radiated from the theme center.[161][318] At the eastern end of the mall was the Central Mall Lagoon, an 800-foot-long (240 m) elliptical lake with fountains.[301][318] In the southern half of the fairground, the Flushing River was dredged to create Meadow and Willow lakes.[320][301] Several of the fair's fountains had water jets with gas burners, which were illuminated by colored lights.[321] Nightly light shows, with music, took place at the Lagoon of Nations as well.[263]

Pavilions and attractions

Pavilions and attractions generally fell into one of three categories: exhibits sponsored by the WFC or private companies; government exhibits; and amusement attractions.[318] The WFC subleased the land to exhibitors, charging different rates based on the sites' proximity to major paths.[91] There were 1,500 exhibitors on the fair's opening day, representing about 40 industries.[161] Because the fairground was built atop swampy land, many of the largest buildings had to be placed on steel-and-concrete decks, pilings, or caissons.[322][323] Thousands of Douglas fir timbers were driven into the ground to act as pilings for the fair structures.[323][324] In addition to the pavilions and amusement rides, the fairground had a marina, as well as hundreds of fountains, toilets, and benches.[121]

The fair had about 375 buildings,[lower-alpha 3] of which 100 were developed by the WFC;[326] the commission reserved about 500,000 square feet (46,000 m2) for its own structures.[122] The buildings included design features such as domes, spirals, buttresses, porticos, rotundas, tall pylons, and corkscrew-shaped ramps.[327][328] Many buildings' steel frames were bolted together so they could be easily disassembled.[121][325] Most of the attractions were in the central exhibit area, covering 390 acres (160 ha).[114][161] The pavilions were mostly illuminated by artificial light;[328][329] most of the illumination came from 30 miles (48 km) of fluorescent lighting tubes, though some attractions used mercury lamps or fluorescent pylons.[330] Additional pinwheel-shaped lights and 10,000 more lightbulbs were installed for the 1940 season.[331]

Zones

The Trylon and Perisphere theme center was designed by Wallace Harrison and Max Abramovitz;[332] the Trylon was a 610-foot (190 m) tower (originally designed to be 700 feet tall), while the Perisphere was a sphere 180 feet (55 m) across.[333][lower-alpha 4] North of the theme center was the Communications and Business Systems Zone, which was centered on the Communications Building, a structure flanked by 160-foot-high (49 m) pylons.[335][336]

The Community Interest Zone was located just east of the Communications & Business Systems Zone.[337] The region's exhibits showcased several trades or industries that were popular among the public at the time, such as home furnishings, plumbing, contemporary art, cosmetics, gardens, the gas industry, fashion, jewelry, and religion.[338]

The Government Zone was located at the east end of the fair, on the eastern bank of the Flushing River. It contained a centrally located Court of Peace, a Lagoon of Nations, and a smaller Court of States.[339][318] The Hall of Nations consisted of eight buildings,[318] which flanked the Court of Peace.[340] Countries could build their own pavilions, lease space in the Hall of Nations, or do both.[341] Most of the U.S. state pavilions were located around the Court of States, which had a lagoon,[342][343] and replicated notable buildings or architectural styles in each state.[318][344]

Southwest of the Government Zone was the Food Zone, composed of 13 buildings.[345] Its focal exhibit, Food No. 3, had four shafts representing wheat stalks.[346][347]

The Production and Distribution Zone was dedicated to showcasing industries that specialized in manufacturing and distribution.[348][349] The focal exhibit was the Consumers Building (also the Consumer Interests Building),[350] an L-shaped structure illustrated with murals by Francis Scott Bradford.[351] Numerous individual companies hosted exhibitions in this region. There were also pavilions dedicated to generic industries, such as electrical products, industrial science, pharmaceuticals, metals, and men's apparel.[352]

The Transportation Zone was located west of the Theme Center, across the Grand Central Parkway.[353] It was connected to the rest of the fairground by two crossings known as the Bridge of Wheels and the Bridge of Wings.[318] The focal exhibit of the Transportation Zone was a Chrysler exhibit group.[354] The Transportation Zone also included large exhibits by companies such as Ford Motor Company and General Motors, in addition to buildings for the aviation, railroad, and maritime industries.[355]

The Amusement Area was located south of the World's Fair Boulevard, covering 230 acres (93 ha)[356][133] or 280 acres (110 ha) on the east shore of Fountain Lake.[114] This area was shaped like a horseshoe surrounding Meadow Lake,[133] and it lacked a traditional midway; instead, it was divided into more than a dozen themed zones.[108][357] The Amusement Area contained numerous bars, restaurants, miniature villages, musical programs, dance floors, rides, and arcade attractions.[358][133] Due to the popularity of nude or seminude performances at the Golden Gate International Exposition, similar shows were presented in the Amusement Area.[359]

Standalone exhibits and structures

There were two focal exhibits that were not located within any zone. The first was the Medical and Public Health Building on Constitution Mall and the Avenue of Patriots (immediately northeast of the Theme Center), which contained several halls dedicated to health.[360][361] The other was the Science and Education Building, just north of the Medical and Public Health Building.[362] The administration building was at the western end of the fairground,[100] and there was also a Manufacturers Trust bank branch.[363]

Transportation

Whalen predicted in late 1936 that these lines needed to be able to handle as many as 800,000 visitors per day, though he predicted an average of 250,000 daily visitors. As such, several public transit lines were built or upgraded to serve the fair.[365] A special subway line, the Independent Subway System's (IND) World's Fair Line was constructed;[366] it operated as a spur of the IND Queens Boulevard Line[367] and was dismantled after the fair ended.[368] The Willets Point station on the Flushing Line was rebuilt to handle fair traffic on the Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT) and Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit (BMT) systems.[369][364] A special fleet of 50 World's Fair Lo-V subway cars were built,[370] and the existing Q-type Queens subway cars were rebuilt to provide additional service on the Flushing Line.[371] A Long Island Rail Road station (now Mets–Willets Point) was built next to the Flushing Line station.[369] In addition, Queens-Nassau Transit Lines bought 55 buses to serve passengers heading to the fairground,[372] and a water taxi service traveled to the fair from City Island, Bronx.[373]

There were also several modes of transit traveling around the fairground itself.[374][375] General Motors manufactured 100 buses specifically for the fair;[376] Exposition Greyhound Lines operated the buses, which connected with each of the fairground's entrances.[374][375] The original plan called for two bus routes, though this was expanded to seven routes soon after the fair opened.[377] There were also tractor trains that traveled along the fairground's paths, as well as tour buses that gave one-hour-long tours of the fair. In addition, visitors could rent one of 500 rolling chairs, each of which had space for one or two people.[374][375] Boats also traveled around Fountain Lake (now Meadow Lake), stopping at seven piers.[375] For a fee, visitors could ride a 40-passenger motorboat across Meadow Lake to the Florida pavilion.[378]

Several highway and road improvements were conducted in advance of the World's Fair.[379] These included the completion of Horace Harding Boulevard,[380] the opening of the Bronx–Whitestone Bridge and Whitestone Expressway,[381] the extension of Grand Central Parkway,[382] and the widening of Queens Boulevard.[383] Markers were placed at intersections throughout the city to direct motorists to the fairground,[384] and several highways to the fairground were outfitted with amber lights.[385] Maps also touted the fairground's proximity to five airports and seaplane bases.[386][lower-alpha 5] During the fair, the Civil Aeronautics Authority temporarily banned most planes from flying over the fairground, except for planes taking off or arriving at the nearby airports.[387]

Culture

Themes and icons

The fair was themed to "the world of tomorrow".[75][76] The colors blue and orange, the official colors of New York City, were chosen as the official colors of the fair.[388] The fair's official seal depicted the Statue of Liberty with her torch, which was available in multiple color scheme.[389] The fair's official flag was originally a triband with a blue bar flanked by orange bars; there was a white seal in the center of the blue bar.[390]

Another theme of the fair was the emerging new middle class. The Westinghouse Electric Corporation produced the film The Middleton Family at the New York World's Fair, which depicted a fictional Midwestern family, the Middletons, taking in the fair.[391][392] The Perisphere's Democracity exhibition envisioned middle-class "Pleasantvilles" arranged around a central hub.[393]

Arts

Music

The WFC established a music advisory committee for the fair in 1937, which was led by the conductor Allen Wardwell.[394] The music advisory committee proposed hosting a festival at the fairground and other places in New York City.[395] About 500 groups signed up to perform at the fair,[396] and music festivals also took place at Carnegie Hall and the Metropolitan Opera House in Manhattan.[397] New York Times music critic Olin Downes was the fair's music director;[398] he selected Hugh Ross to organize recitals and concerts at the Temple of Religion.[399] Eugene La Barre led the World's Fair band, which was composed of 56 musicians,[400] and the WFC held a competition to select three songs for the band to perform.[401] Unlike in the 1939 season, the fair had no organized music program during 1940. Instead, the fair's orchestra played songs on request during 1940; on an average day, they received more than 1,200 requests and played over 200 songs.[396]

Several theme songs were written for the fair, none of which caught on.[402] William Grant Still recorded the song "Rising Tide",[403][404] a three-minute tune that was played continuously during the 1939 season.[405] "Dawn of a New Day", one of George Gershwin's final songs, was also recorded for the fair.[402][406] La Barre's "For Peace and Freedom" was selected as the 1940 season's theme song.[407]

Films and stage shows

The fair hosted eight musical shows during the 1939 season and seven musicals during 1940.[408] For instance, Billy Rose staged his Aquacade musical,[409] and the fair had a musical pageant called the American Jubilee.[410] In addition, The Hollywood Reporter estimated that 500 movies would be screened at the fair;[411] ultimately, exhibitors screened 612 films during the first season.[412] The fair had 34 auditoriums during the 1939 season, which were operated by 19 nations' governments, in addition to industrial exhibitors and city-government agencies.[412] During the 1940 season, the fairground had 30 movie-theater auditoriums with an estimated 6,200 seats.[413] The fair showcased not only feature films but also non-theatrical motion pictures, including both silent films and sound films.[414] These motion pictures were all shot on 16 mm and 35 mm film.[412][413]

Visual art and sculpture

From the outset, the fairground was planned to include decorations,[415] particularly large murals, sculptures, and reliefs.[416] Initially, however, there were no plans to exhibit contemporary art at the fair.[417][418] After observers criticized the fair's lack of formal art galleries, Whalen agreed to include a community art center,[417] and the WFC also held art competitions for muralists and sculptors.[418] Eight hundred contemporary American artworks from the 48 states were exhibited at the fair during 1939,[419] and a rotating display of American art was showcased in 1940.[420] At the Masterpieces of Art building were hundreds of rare paintings;[421] during the 1940 season, even more paintings were shown.[422] The WFC bought some of the fair's artwork and distributed it across the U.S. after the fair.[423] In addition, foreign governments sponsored exhibits of sculptures and visual art in their respective pavilions.[424]

Whalen, who was determined that the fair should "not represent the work of any one person or school", employed 181 visual artists, designers, and architects.[425] Many of the buildings' facades were decorated with murals, commissioned by both the WFC and individual exhibitors[426][427] in about 100 colors.[428] There were about 105 murals at the fair,[243] which measured as large as 250 by 60 feet (76 by 18 m). The murals were executed in a variety of materials, such as metal strips, mosaic tiles, and paint. The WFC's board of design approved murals based on how well they harmonized with the surrounding buildings; for example, murals near the theme center were designed in muted colors, while murals on modern-style buildings were more colorful.[427] Although artists could design murals even if they were not part of a labor union, only union members could paint the actual murals.[429] The New York Times called it "the largest program of exterior mural painting ever undertaken",[427] while the New York Herald Tribune said that "never before has mural decoration been attempted on so large or lively a scale".[427] Works Progress Administration artists painted murals for the fair as well.[430] Ernest Peixotto oversaw the development of the murals and the fair's color-coding system.[431]

The fair also included 174 sculptures.[243] The largest statue at the fair was James Earle Fraser's 65-foot-tall (20 m) sculpture of George Washington,[432] which stood in the middle of the fair's Constitution Mall.[433] The Times credited Lee Lawrie—who oversaw the installation of the fair's artwork—with describing the sculptures as "an essential part of the fair".[432] Three of the sculptures were intended to be preserved after the fair: Robert Foster's Textile, Lawrence Tenney Stevens's The Tree of Life, and Waylande Gregory's Fountain of the Atom.[432] Textile depicted an abstract sheet-steel figure,[434] The Tree of Life was carved out of a 60-foot-tall (18 m) elm tree,[435] and Fountain of the Atom consisted of small ceramic figures.[436] Various temporary sculptures, many of which were made of plaster, were placed on buildings.[432]

Consumer products

The fair focused significantly on consumer products that happened to include scientific innovations, rather than presenting scientific innovations in their own right.[437] Products shown at the fair included RCA televisions, a Crosley vehicle from 1940, and a Novachord organ manufactured by The Hammond Organ Company,[393] along with nylon, cellophane, and Lucite.[243] Other objects included Vermeer's painting The Milkmaid from the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam,[438] a streamlined pencil sharpener,[439] a diner (still in operation as the White Mana in Jersey City, New Jersey[440]), a futuristic car-based city by General Motors,[439][353] and the first fully constructed computer game.[441] In addition, older objects were displayed at the fair, such as a model of the world's first bicycle.[442]

Electronics were showcased at the fair. The IBM exhibit displayed the Radiotype writing machine, and RCA displayed various types of machinery in a "television laboratory".[141] RCA and NBC agreed to host television demonstrations at the World's Fair.[443] These TVs displayed several programs, including the first televised Major League Baseball game; a program from WRGB-TV in Schenectady, New York; and performances of the play When We Are Married.[444] Westinghouse's exhibit featured Elektro the Moto-Man, a robot that talked, differentiated colors, and smoked cigarettes.[445] Bell Labs' Voder, a keyboard-operated speech synthesizer, was demonstrated at the fair.[243][446] Other futuristic exhibits included General Electric's home of tomorrow, as well as the 15 homes in the Tomorrow Town exhibit.[243]

Food

For the 1939 season, there were at least 40 restaurants with a combined 23,000 seats, in addition to 261 refreshment stands.[447] Cuisine from 24 participating countries was served at the fair.[448] These included caviar in the Romanian and Polish pavilions; borscht, blini, and pelmeni from the Soviet pavilion; soufflés from the French pavilion; smorgasbords from the Swedish pavilion; and kebabs and honey desserts from the Albanian pavilion.[448][447] A New York Times article from 1964 characterized bicarbonate of soda as the 1939 fair's most popular soda.[449] The WFC also awarded quick-service food concessions to companies such as Childs Restaurants, Longchamps, and the Brass Rail.[450] The concessions included 80 hot-dog stands,[165] in addition to 59 soda stalls, 38 root beer stands, and 25 popcorn stands.[111]

The city government also appointed 36 inspectors to enforce food safety at the fair.[451] During the fair's first season, there were complaints that the food was too expensive;[176] one New York Times report found that restaurants were charging as much as $2.50 (equivalent to $54.76 in 2023) for à la carte meals.[450] For the 1940 season, there were 70 restaurants and between 150 and 235 concession stands at the fair.[265][452] The WFC introduced regulations during the second season, restricting restaurateurs from drastically increasing food prices.[252] Throughout both seasons, the fair sold an estimated 16.2 million hot dogs, 8.3 million burgers, 5.1 million doughnuts, and 2.7 million cups of beer.[453]

Other events

Participating countries, U.S. states and territories, New York counties, businesses, and organizations were given special theme days at the fair, during which celebrations were held.[454] A different button was issued for each theme day.[455] During the fair, there were fireworks displays on the lagoon, as well as colorful searchlights illuminating Meadow Lake.[318]

The fair coincided with the 1st World Science Fiction Convention,[456][457] which took place at the Caravan Hall in Manhattan on July 2–4, 1939.[458] In addition, on July 3, 1940, the fair hosted "Superman Day",[273][459] which included an athletic contest and a public appearance by an actor portraying Superman.[459] Broadway actor Ray Middleton, who served as a judge for the contest, is credited with having appeared in the Superman costume on Superman Day, but this is disputed.[460] Sporting events throughout the New York City area were also planned in conjunction with the World's Fair,[461] and the WFC sponsored a sports camp for boys during both seasons.[462]

Aftermath

Site and structures

Demolition began the day after the fair ended.[463] Almost all structures had to be removed within 120 days of the fair's closure,[325][464] and the vast majority of structures were dismantled or moved shortly after the fair's final day.[465] Valuable exhibits, artwork, and historic artifacts were relocated.[463] On October 29, hundreds of workers went on strike to protest the removal of equipment,[466] which delayed all work on the site.[467] The strike ended after ten days.[468] Within a month of the fair's closure, many of the structures had been demolished, and workers were restoring the landscape.[469] Cables and other materials were removed and sold for scrap,[325][470] and there were proposals to melt down the buildings' structural steel into scrap metal for the U.S. war effort.[471] During the fair's demolition, five men were killed when one of the buildings' ceilings collapsed.[472]

Despite a citywide moratorium on new construction, La Guardia provided funding to convert the fairground into parkland,[473] although only $750,000 was provided for this purpose.[474] Work on the park began in December 1940,[475] and Flushing Meadows Park opened the next year.[476] The park hosted the 1964 New York World's Fair, which began on April 22, 1964,[477] and ended on October 17, 1965;[478] the site again reverted to park use in 1967.[479] The NYPD's Flushing Meadows precinct was disbanded in 1952,[480] but the Queens traffic division (which had been established to manage traffic during the fair) continued until 1972.[481]

Seven structures were preserved as part of the park.[464][465][lower-alpha 6] By the 1960s, only two of the fair's original structures remained, the New York City Pavilion and the Billy Rose's Aquacade amphitheater,[482] though the Aquacade was torn down in the 1990s.[483] The fair's esplanade, five bridges, and the World's Fair Marina were preserved as well,[484] but the fountains were demolished.[325] Many amusement rides were sold to Luna Park at Coney Island;[485] the Parachute Jump was sold and relocated to Steeplechase Park, also in Coney Island.[486] Other buildings that were relocated included a structure from the fair's Town of Tomorrow exhibit,[487] as well as the Belgian Building.[488] Some of the buildings' glass bricks were salvaged and used elsewhere.[489] Furniture, equipment, and decorations were sold off.[325] There were suggestions to preserve additional buildings as a training military camp, but the United States Armed Forces had rejected the idea.[490]

Foreign exhibits and staff

Initially, the U.S. government had not imposed customs duties on foreign exhibits because it anticipated that the exhibits would be repatriated after the fair.[491] Customs duties were imposed on exhibits that remained in the U.S. after the fair.[492] Afterward, the exhibits could be sent back to their home country, retained in the U.S., destroyed, or sold.[325][492] However, many nations could not send their exhibits back home due to World War II,[492][493] and President Roosevelt had temporarily frozen the assets of seven foreign exhibitors because their countries had been invaded.[494] Many European pavilions' staff were also unable to return home due to the war;[495][496] The New York Times estimated that 350 foreign staffers could not easily return home,[497] while the New York Herald Tribune put the number of affected employees at 400.[498] In response, U.S. representative John J. Delaney introduced legislation in October 1940 to allow these workers to remain in the U.S.[493][499]

Several countries in German-occupied Europe donated or lent their World's Fair exhibits to institutions across the United States.[500][501] Most of the Polish pavilion's items were sold by the Polish Government in exile to the Polish Museum of America, except for the monument of the Polish–Lithuanian King Jagiełło. which was reinstalled in Central Park.[502] The British pavilion's copy of the Magna Carta remained in the U.S.,[503][500] and a panel from that pavilion depicting George Washington's lineage was sent to the Library of Congress.[504] In addition, some French artwork displayed at the fair was lent to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan,[505] and other artwork from that pavilion was displayed at the Riverside Museum.[506] Three French restaurants from the fair—La Caravelle, Le Pavillon, and La Côte Basque—reopened in Manhattan.[507] Objects from the Swedish, Turkish, and Canadian pavilions were also retained in New York City.[498]

The WFC also had to dispose of Axis countries' exhibits. The U.S. government seized the Italian State Railways' train display and melted it down for scrap,[508] while it sold off binoculars from the Czechoslovak pavilion and wine from the Rumania pavilion to pay customs duties.[503] There were several unsuccessful attempts to give away the Italian pavilion's Guglielmo Marconi monument,[509] and the Hungarian pavilion's statue of Saint Istvan was not given away until 1956.[510]

Profitability and dissolution of WFC

When the fair closed, the WFC initially predicted that the fair would recoup 38.4% of its cost[511] (later revised to 39.2%).[512] The WFC ultimately recovered only 32% of its original expenditure.[513][514] Despite the fair's overall unprofitability, the Amusement Area recorded a net profit.[515] In total, the WFC earned $3.9 million during the 1939 season and $3.4 million during the 1940 season.[516] The WFC paid bondholders $2.08 million in early 1941[517] and made their final payments to bondholders in June 1942.[40] For several years, the WFC retained a small staff to close out its financial accounts.[518] The corporation was not formally dissolved until August 1944;[519] at the time of its dissolution, the WFC owed shareholders $19 million.[40][520]

Impact

Reception

When the fair was being developed, The Washington Post wrote in 1936 that the fair would give New York City a permanent public park, while the "visitors will get an eyeful beyond their fondest imagination and the hotel-keepers will get a pocketful" of money.[6] The Post wrote in 1938 that the fair would become "the cynosure of millions upon millions",[8] while The New York Times said the event "will still be a great fair" even if half the buildings were never built.[121] Another newspaper wrote that the fair (along with the Golden Gate Exposition) would be "two stunning examples of science in action".[521] Just before the fair opened, The Scotsman wrote that, despite the ongoing Nazi conquest of Europe, workers at the 1939 fair "still [believed] the world of to-day has possibilities of progress".[522]

Upon the fair's opening, a Washington Post writer praised the fairground's futuristic architecture and landscaping, even while stating that "there is also architecture on which the classicist can rest his peepers".[523] The New York Times reported that European countries regarded the fair as an opportunity to display "its particular political views before the American public under the guise of good-will and commercial display".[524] In an August 1939 Gallup poll of the fair's visitors, 84% of respondents said they wanted to return, while only 3% disliked the fair.[525]

When the fair closed, the Baltimore Sun wrote in 1940 that "the World's Fair was devoted to the arts of peace, and this is time of war".[526] A decade after the fair, one writer for the New York Herald Tribune said the expo had "become for many of us a symbol of the past", in large part because of the war that followed.[527] In 1964, one New York Times writer said the 1939 fair had been envisioned in an era "that had in its calendar no World War II, no Hiroshima, no Korea, no fires in Africa and Asia".[449] The design critic Paul Goldberger, writing about the fair in 1980, described the fair as significant for the products introduced there and for its architecture,[393] while a Newsday critic wrote the same year that the fair had provided hope at a time when everyone was fearful of the war.[222] Robert A. M. Stern wrote in his 1987 book New York 1930 that "the fair was seen as little more than a transitory good-time place".[11]

Economic and regional influence

To limit excessive real-estate development around the fairground, city officials requested in early 1936 that the neighborhoods around Flushing Meadows be rezoned as residential areas.[528] The Board of Estimate voted in 1937 to enact zoning restrictions around the fair, which prevented the construction of high-rise buildings around the site and created a buffer zone around the fairground.[529] The same year, the city restricted businesses from operating within 1,000 feet (300 m) of the fairground.[530] One New York Times writer wrote in 1938 that, although residential development in Queens was increasing, this was due to the presence of new transport links, rather than because of the fair.[531] After the fair began, commercial activity around Flushing, Queens, also increased, and real-estate prices there increased several times over.[2]

Grover Whalen predicted that the fair would attract 50 million visitors who would spend $1 billion in total.[532] The WFC projected in 1936 that it would lose $3.9 million if the fair recorded 40 million visitors and that it would earn at least $1 million if it had 50 million or more visitors.[533] Numerous retailers on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan renovated their buildings for the fair,[534] and room rates at local hotels were also increased.[535] By May 1939, real-estate figures predicted that the fair would earn between $1 billion and $1.5 billion for the city's economy.[139] The New York City Council also proposed waiving sales taxes for exhibitors during the fair, though La Guardia vetoed the bill for being too vague.[536] The state legislature predicted that the fair would spur business throughout New York state,[537] and Whalen predicted that the fair would increase total spending across the U.S. by $10 billion.[538] During the fair, the New York state government sought to attract visitors to other parts of the state, such as the Finger Lakes, Adirondack Mountains, and Catskill Mountains.[539]

During the 1939 season, New York City saw both increased vehicular traffic and public-transit use, even though the city actually had fewer commuters (continuing a decade-long trend).[540] Vehicular traffic in Manhattan south of 61st Street increased during the fair,[541] as did hotel-room bookings in the city.[542] The exposition also spurred increased spending in New York City and was indirectly connected with Queens's further development.[2] Although most tourists to New York City in 1939 came specifically for the fair, the rest of the city also saw increased tourism in 1940.[543]

Media and archives

After the fair, documents and films from the event were sent to New York Public Library,[544] where they are still maintained.[545] The National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., described the 1939 fair in its exhibition Designing Tomorrow: America's World's Fairs of the 1930s, which ran from October 2010 to September 2011.[546] In addition, the Queens Museum hosted a retrospective exhibit about the fair in 1980.[222][393] Private collectors have amassed a large amount of memorabilia from the fair. These include print media such as guidebooks, posters, and programs, in addition to everyday objects such as pens, ashtrays, maps, and puzzles.[547]

The 1939 New York World's Fair has been dramatized in books such as David Gelernter's 1995 novel 1939-The Lost World of the Fair.[548] There have also been several nonfiction books about the fair, including Barbara Cohen, Steven Heller, amd Seymour Chwast's 1989 book Trylon and Perisphere[243] and James Mauro's 2010 book Twilight at the World of Tomorrow.[549] In addition, objects and footage from the event are shown in the 1984 documentary The World of Tomorrow.[550]

See also

- Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations – 1853 World's Fair in Bryant Park, New York City

- List of world expositions

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.