Monument to Nicholas I

Equestrian statue in Saint Petersburg, Russia From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Monument to Nicholas I (Russian: Памятник Николаю I) is a bronze equestrian monument of Nicholas I of Russia on St Isaac's Square (in front of Saint Isaac's Cathedral) in Saint Petersburg, Russia. It was created by French sculptor Auguste de Montferrand and unveiled on July 7 [O.S. June 25] , 1859, the six-meter statue was considered a technical wonder at the time of its creation. It is one of only a few bronze statues with only two support points (the rear hooves of the horse).[1]

Russian: Памятник Николаю I | |

Current state after restoration (2023) | |

| |

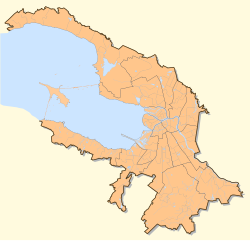

| 59°55′55″N 30°18′30″E | |

| Location | St Isaac's Square in Saint Petersburg, Russia |

|---|---|

| Designer | Auguste de Montferrand is the project head, the architect. Sculptors: Peter Klodt, Robert Salemann, Nicholas Ramazanov Architects: Ludwig Bohnstedt, Roman Weigelt |

| Type | Equestrian statue |

| Material | Bronze is a sculpture, high reliefs, letters, a fencing; Pedestal is a red, grey granite, the shohansky porphyry, the Italian marble |

| Height | 16.3 meters full, Equestrian statue is 6 meters |

| Opening date | July 7, 1859 |

| Dedicated to | Nicholas I of Russia |

Overview

Summarize

Perspective

The Neo-Baroque monument to the Russian ruler Nicholas I was designed by the French-born architect Auguste de Montferrand in 1856. When he planned the registration of Saint Isaac's Square, the uniform architectural ensembles of the Palace Square (in 1843) and the Senate Square had already been finished (in 1849). Monuments to the emperors Peter I and Alexander I dominated these squares. By tradition, de Montferrand intended to construct a monument on the new site, to unite the buildings of different architectural styles already there.[2]

At the personal request of his successor Alexander II, Nicholas was represented as a prancing knight, "in the military outfit in which the late tsar was most majestic".[3] Around the base are allegorical statues modelled on Nicholas I's daughters and personifying virtues. The statue faces Saint Isaac's Cathedral, with the horse's posterior turned to the Mariinsky Palace of Nicholas's daughter, Grand Duchess Maria Nikolayevna. This was said[by whom?] to have caused the Grand Duchess considerable discomfort.

The monument also depicts the social activities of the emperor: Nicholas I was for many years the chief of the nearby Konnogvardejsky regiment. Elements of the city topography, the Konnogvardejsky parkway and Konnogvardejsky lane, and the Konnogvardejsky arena are combined with the Konnogvardejsky regiment uniform in which the emperor is dressed.[4]

Soviet historians and critics considered it a 'composite-stylistic' monument because they thought its elements did not combine to form a uniform composition:[5][6]

- The pedestal, the reliefs on a pedestal, the azid, and the equestrian statue were not subordinated to a uniform idea and in some measure contradicted each other.

- The forms of a monument were crushed and overloaded by fine details, and the composition was elaborate and unduly decorative.

However, some aspects of the composition were considered positive:[5][6]

- The composition answered the appointed purpose and it complemented the other monuments in the surrounding squares giving it completeness and integrity.

- The monument was professionally made by experts, and the artistic value of its elements is beyond doubt.

Legends connected with the statue

Contemporaries noticed that Peter the Great was the idol of Nicholas I who had in all things tried to imitate his glorious ancestor.

The ballerina Mathilde Kschessinska (1872–1971), who was a favourite of Nicholas II, was offered the Mariinsky Palace as a place of residence. She refused, with the rejoinder that two emperors had already turned away from an ill-fated building and Nicholas did not want to be the third to join them. By this reference to 'two emperors' Kschessinska meant the statues of the Bronze Horseman and the Monument to Nicholas I. Later similar rumours began to be attributed to the Grand Duchess Maria Nikolayevna of Russia. However this legend has been called into question because Maria actively participated in work on the monument.[7]

Contemporaries have noticed that this monument is aligned with the statue of the Bronze Horseman, and is almost an identical distance from Saint Isaac's Cathedral. This juxtaposition has generated numerous jokes of the type "Kolya to Petia catches up, but Isaak's Cathedral disturbs!" Russian: Коля Петю догоняет, да Исакий мешает!

There is also a city legend, which claims that the day after the monument was unveiled, on a foot of the horse there was found a wooden tablet on which had been written: "you will not catch up!". On the basis of this legend in the 19th century in St. Petersburg there was a saying: "the Fool of the clever catches up, but the monument to it disturbs" Russian: Дурак умного догоняет, но памятник ему мешает![8]

Russian: В нём (Николае I) много от прапорщика и мало от Петра Великого

Translated: In him (Nikolas I) there is a lot from an ensign and little from Peter the Great[8]

In the Soviet era there was a legend about the uniqueness of the design of the monument, that its axle load distribution was executed by lead shot. But when the monument was subjected to restoration in the 1980s, no trace of any lead shot was found inside it.[4]

Erection of the monument

Summarize

Perspective

On the first anniversary of death of emperor Nikolas I (in February 1856) Emperor Alexander II had published a command to begin of designing a monument. Architect de Montferrand received the commission to present "reasons about a monument to Nikolay I" (Russian: соображения о памятнике Николаю I). In May 1856 de Montferrand's project was confirmed and in June the monument installation site was defined: "opposite to the Mariinsky Palace, faced to the Isaakievsky cathedral" (Russian: напротив Мариинского дворца, лицом к Исаакиевскому собору).[2]

Horse figure

Several different sculpture models were used in creating the monument. A large model of the horse which Nicholas I sits on was commissioned from the Tsar's favourite sculptor, Peter Klodt. The initial sketch represented the horseman at rest. The author planned by means of a mimicry and gestures to reflect character of the emperor, but this variant was rejected by de Montferrand for the reason that could not serve the primary purpose of association of spatial ensembles.[5]

Klodt created the new sketch in which it is represented a horse in movement, leaning only on back pair feet. It is composite, the prompt pose of a horse is resisted by the smart figure of the emperor extended in a string. For an embodiment of this sketch the sculptor precisely calculated the weight of the horse figure, leaning only on two points of support.[5] On de Montferrand's drawing sculptor Robert Salemann executed the monument's model "in 1/8 full sizes with all architectural parts and ornaments" (Russian: в 1/8 натуральной величины со всеми архитектурными частями и украшениями).[2] This variant was accepted by the architect and the emperor, it is embodied in bronze; this model has remained and is in a museum of a city sculpture.

Base of a statue

On it high reliefs which are devoted key episodes of the thirty-year reign of Nicholas I have been fixed:

- December 14, 1825

- On a high relief the young emperor goes on the area for suppression Decembrist revolt on December 26 [O.S. 14th] 1825 transferring to hands of soldiers of sentry of the son of the successor (the future Emperor Alexander II). The sculptor Ramazanov, the high relief are cast in masterful Academy of Arts under the direction of Peter Klodt.[2]

- February 14, 1831

- The left-hand side high relief represents Nikolay I who has arrived on February 14, 1831 on the Sennaya Square, having stopped cholera riot. The author is sculptor Ramazanov, the high relief are cast in masterful Academy of Arts under the direction of Peter Klodt.[2] The relief contains some historical errors:

- The emperor did not end a cholera outbreak, it had finished already after government intervention.

- The specified events occurred not on February 14, but on June 22, 1831.

Most likely, this error is admitted for the first time in work of Marquis de Custine "La Russie en 1839",[9] in which it confuses the cholera revolt of 1831 to an episode of 1825 (Decembrist revolt). Russian researcher Nikolay Shilder has specified this error in his works.[10]

- January 20, 1833 or Delivery of the Codification of Law to Count Mikhail Speransky

- The certificate of rewarding of Mikhail Speransky of Nicholas I Is represented: the emperor removes from itself a tape of an Order of St. Andrew. It was mainly through the work of Speransky that a new code was introduced during Nicholas I's reign in January 1835, marking a milestone in Russian legal history. Date specifies decree signing about rewarding has been signed. The author is sculptor Salemann, the High relief are cast in masterful in Galvanic institution of Maximilian, Duke of Leuchtenberg.[2]

- November 13, 1851

- Survey by the emperor of Verebinsky bridge on Nikolaevskaya railway between Petersburg and Moscow at the first journey on this road. The sculptor is Ramazanov, the high relief are cast in masterful in Galvanic institution of Maximilian, Duke of Leuchtenberg.[2]

On pedestal corners allegorical figures of Justice, Force, Wisdom and Belief to which portrait similarity to Empress Alexandra Feodorovna and her daughters is given: grand duchesses Alexandra, Maria and Olga.[2]

The Russian masters Nikolai Ramazanov and Robert Salemann designed for the monument's pedestal. Salemann also sculpted the four allegorical female figures, steel fixtures, ornaments on the pedestal. The pedestal stands on a short platform made of red Finnish granite with three steps. The lower part of the pedestal is of dark gray granite and red porphyry. The middle part, hewn from a block of red Finnish granite, is decorated with bronze bas-reliefs. The upper part of the pedestal is made of red porphyry. The pedestal of the horse statue is made of white Italian marble.

Registration Base of a statue have added with graceful lanterns-floor lamps with fixtures, they are made on de Montferrand's plan, the project was executed by architect Robert Veigelt. In 1860 the monument composition was finished by a bronze lattice from twenty links. The lattice project belongs to architect Ludvig Bonstedt. All these elements are cast in Galvanic institution of Maximilian, Duke of Leuchtenberg.[2]

Safety and restorations

Summarize

Perspective

The monument's technical proficiency was cited as a reason why this statue — the only one from a cluster of outdoor sculptures representing 19th-century Russian royalty — survived the Soviet period virtually intact. However, a bronze fencing around the monument, first installed in 1860, was dismantled in 1940. During World War II the monument was covered by a case from the boards, filled with bags of sand.[2]

In 1987–1988 the State Museum of City Sculpture undertook a full restoration of the monument. Restorers opened the hatch on a croup of the horse, surveyed the condition of the internal skeleton, and engaged in complex technical expert appraisal, including gamma-ray examination of the feet of a horse. Lost fragments were recreated, inserts in bronze, granite, and marble were made. Gilding of signs on an inscription by galvanic way was made.[2]

In 1991–1992 restorers cast new fencing using the sample of a link which has remained, using funds of the Museum of City Sculpture. Works were executed by the factory "Monumentskulptura".[2]

Russian: Есть подозрение, что нарушилась герметичность блоков мрамора и известняка, под мрамор попадает влага, а это очень вредно для постамента

Translated: There is a suspicion that hermetical tightness of marble and limestone blocks has been broken, and the marble is getting moist within, which is very harmful for a pedestal.[11]

press relations service of State museum City sculpture

In 2009 the State Museum of City sculpture made an inspection of the base of the statue. Julia Loginova was managing the maintenance of monuments, work supervision. Results of the research were to be available on 15 October, and based on them the museum would estimate the amount of works which would begin at the end of 2009.[needs update][11]

Notes

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.